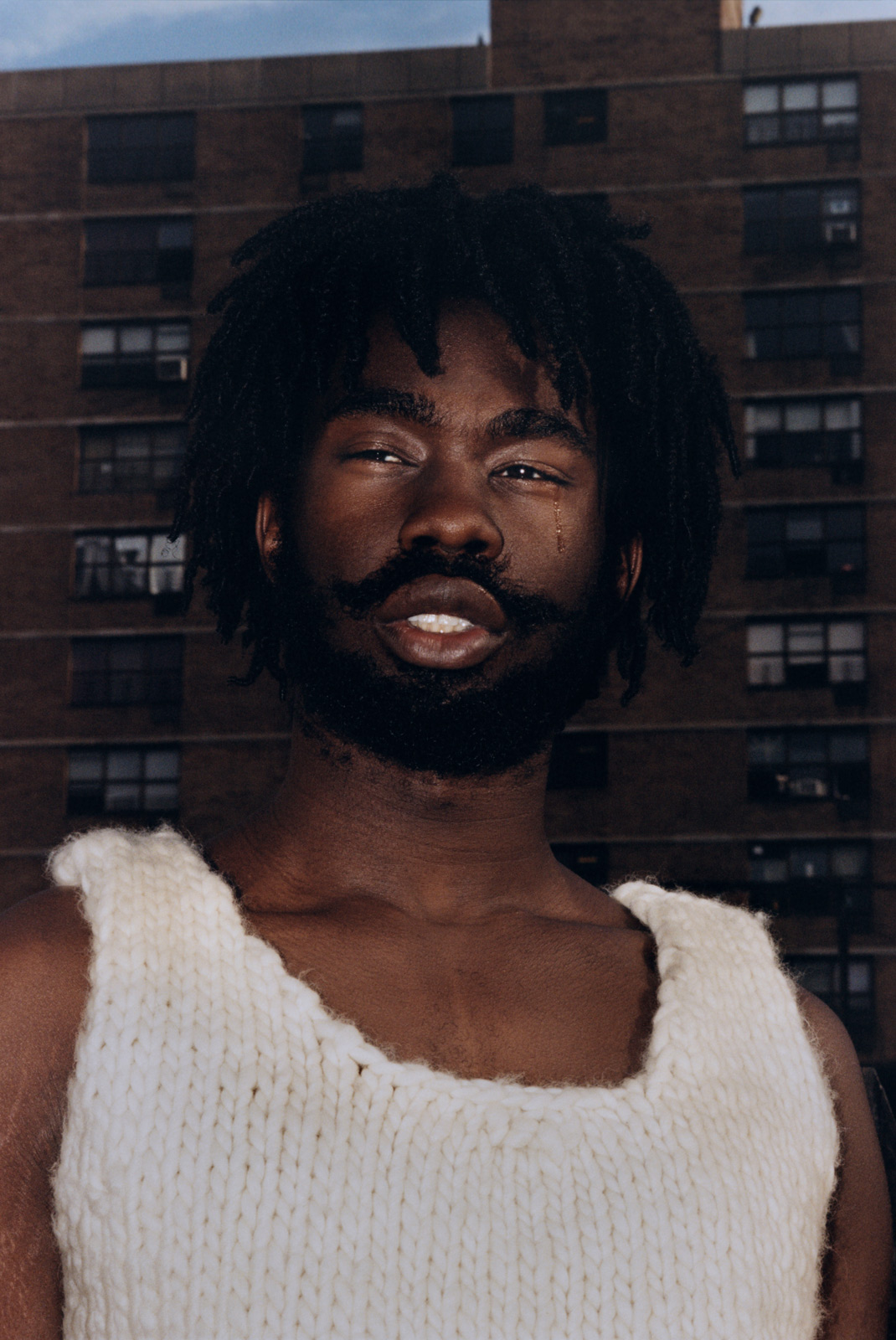

In his first US solo show, ‘I Can Make You Feel Good,’ the photographer imagines a world where black-skinned bodies are free to just exist.

What would a black utopia look like? With his first US solo exhibition, I Can Make You Feel Good, photographer Tyler Mitchell reveals how the concept manifests in his own mind. Spanning three rooms at The International Center of Photography, in a multimedia display, Mitchell’s show exists at the intersection of intimacy and freedom.

Growing up in the digital age, Mitchell notes that his work was inspired in large part by Tumblr, a platform rife with images of youth portrayed as free, sensual, and—overwhelmingly—white. Mitchell utilizes the tools of documentary photography and filmmaking to show black identity in an equally close and vulnerable light.

In one dark room, a pyramid jets out from the ceiling. Projected on each side is intimate footage of people of color; a group of kids laying together on a picnic blanket, a close-up of a content young man. An adjacent room houses works of Mitchell’s that you’ve probably seen all over Instagram; model Ugbad Abdi in US Vogue, and on the cover of Antwaun Sargent’s The New Black Vanguard; a still of the sandy back of Aweng Ade-Chuol; and a family portrait of Tyra Mitchell, Lordy Ko, and their two children for Document Journal’s Fall/Winter 2018 issue.

Behind a curtain plays a video of black youths enjoying the blissful delights of everyday adolescent moments; eating ice-cream cones, swimming, playing jump rope. These universal leisure activities of white America, ascribed to black youth, serve as a visual reminder that people of color are typically deprived of them; not only in everyday life, but similarly in representation. Mitchell films his subjects from below, in a call-to-action against Hollywood’s racist suggestion that people of color are not heroic nor fit to be looked up to.

The final room contains cotton, linen, and silk draped from laundry lines, featuring screenprints of Mitchell’s photos in a one-of-a-kind collection. Referencing an archetypal domestic space and working individuals of color, these laundry lines are both a tactile symbol and a call back to Mitchell’s time at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, where he would use linens in lieu of seamless backdrops.

We sat down with Mitchell to talk about this installation, his curated concept of black utopia, and his hopes for the future.

Hannah Miller: I want to start by asking what this show means to you ?

Tyler Mitchell: I think the show means many things from different angles. I mean, it’s my first show in the US and my first show in the city I live in. So there’s a lot of people here who I have been in a creative community with, who I’m friends with, who I work with, who are finally seeing my work, not just online or on Instagram. They’re seeing it kind of brought together as a more considered world. Seeing the video installations physically, seeing the photographs physically—it’s a whole different experience, I feel. So, for me, it has that way of finally doing something in the city I live, in my home city.

Hannah: You’ve said before that some of your work is influenced by Tumblr images by Ryan McGinley and Larry Clark, but that they are very under-representative of the black community. If you can talk about that a little and your idea of a ‘black utopia,’ as you put it.

Tyler: People like Ryan McGinley and Larry Clark were just two examples of images that seem to proliferate the most on those types of platforms. They seem to get the most re-blogs or people would always repost them. Their most iconic images would usually be white youths, very sensuous and beautiful, enjoying life in groups in Paris or on road trips, you know So I’m thinking about my experiences and trying to make art about my experiences in the South. Being black and middle class, I think about the self-policing that has to happen within our community here. It’s baked into our psyche that we’re maybe not allowed to, or that we’re not supposed to, behave in those ways outwardly in society or perform those sentiments of joy… Obviously, we do enjoy leisure time, that’s a global thing. But my work is about bringing forward these ideas of leisure and play as radical things, because we’ve societally, politically, and within ourselves—in our psyche—been prevented from enjoying those freedoms. Utopia, by definition, isn’t achievable. Photography, by definition, is about constructing an image and framing an image and a point of view on the world. I’m playing with these ideas, the fantasy of things that are not real, or that I would want to be real.

Hannah: When I’m looking at your images, there is a clear utopic aspect, but it feels almost attainable, just out of reach. I think that’s super rare, we don’t really see that a lot, and it transfers over to some of your other work. I’m wondering how you portray the same idea in your commissioned work, for example, Copper by Comme des Garçons. It felt like you kind of took over and made it like your own.

Tyler: I think the way that commercial images are being made has changed, which has allowed for a beautiful space for someone like me—who has a very personal and autobiographical point of view—to make very successful commercial images. It’s beautiful because, on a practical level, it allows me to live, and get paid for the things that I love, which is making images. Historically, maybe an artist would have to stay away from the commercial world and would have to work their way up through other structures. But I think it’s amazing now that there’s this crossover between [the commercial and] the very personal, emotional sentiments—which, to me, are about visualizing black-skinned bodies; captivating, poetic, effortless, intimate, sensitive, but also strong. And those things translate well in my commercial work. Instagram definitely has something to do with the way that our culture has evolved in general. People are looking now for a more relatable image in a commercial picture rather than something that is too contrived or that we already know isn’t real.

Hannah: Okay. You mentioned Instagram, and social media in general. Does that help shape your work? I know you recently did a photoshoot for i-D with skaters from Nigeria.

Tyler: Infinitely. From the beginning, reaching out to people like Kevin Abstract—at the time, when we connected on the Internet, we were both not at all regarded or, nobody was checking for us when we were both talking to each other. He was living in Texas and I was just starting school here in New York. It’s those reach-outs and those connections across state lines and country lines and continent lines that the Internet has allowed for me. Most of my friends—almost all of my friends—if it weren’t for Instagram, I wouldn’t be connected to… that has allowed me to collaborate on projects that I wouldn’t be able to otherwise; to make music videos for Kevin Abstract, to go to Lagos and photograph these skaters. They reached out to me just through admiration of my work. But then I also admired what they were doing. So we both realized what we were doing was special and hopefully there was a moment we could connect. That’s how I was able to photograph them for the i-D cover and it’s things like that that really keep it special. The Internet has allowed me to make my tribe and my community and and basically look at other people who I admire and try and connect with them.

Hannah: That’s so special. And who are some people that are inspiring you right now?

Tyler: I mean, my life and my home—my whole life source of being able to be creative comes from basically looking at a thousand things at once, like a kitchen sink way of working. I don’t want to relate it to Basquiat, but you know how he would have books out all around when he’s painting, and he’s taking this from that and this and that? That’s very much my way of thinking and working. I’m watching a lot of Edward Yang movies; this Taiwanese-Chinese director is completely unrelated to anything I’m doing, but I’m finding lots of meaning in these epic, sprawling stories about families in Taiwan disintegrating, and young men who are kind of involuntary trapped inside themselves in Taiwan because of the repression of the government. When I’m talking about masculinity and other people that inspire me; Roy DeCarava, obviously, his photographs of the jazz scene and black families in Harlem; Gordon Parks, who was using editorial commissions from Life magazine to do these sprawling photo stories about poverty in Brazil, about poverty in the South, about families in Harlem, about farming in Kansas; Carrie Mae Weems, whose amazing work is ever-expansive. Kevin Abstract is inspiring me. Brockhampton, Kelsey Lu, Frank Ocean. It’s ranging from contemporary all the way back to people who made room for me to exist.

Hannah: You mentioned Gordon Parks. I believe you were named a 2020 fellow under the Gordon Parks Foundation. I’m wondering what you’re doing with that?

Tyler: Deborah Willis, who is my professor—she’s an artist, author, curator, writer and head of NYU Tisch Photography—showed me a lot of his work. She and the director of the Foundation have brought me into their family, if you will. I plan to basically mine [Gordon Parks’] archives and make a project in response to what he was doing with fashion in the ‘40s and ‘50s. And that will show in the fall. The director and Deborah both have been huge supporters of my work. They’ve seen and really understood the ways in which I’m continuing Parks’s legacy. He deeply understood the crossover between commercial and personal artwork, way ahead of a lot of photographers.

Hannah: That’s going to be awesome. You’re gonna have a lot of fun.

Tyler: Yeah, that’s what I’m most looking forward to.

Hannah: I want to know what it was like being at NYU as you were kind of rising up and getting this following.

Tyler: That’s actually a really good question that not many people ask. It’s definitely not without its difficulties because a lot of it is learning on the job. Being young and excited is amazing, but also [means being] constantly tired. Just making this work is exhausting personally, and then putting it out there… But I would say the hardest part is just people’s outer perceptions of being young. I’m someone who likes making this work for me. I realized it’s really therapeutic in a way. As cliche as it may sound, I’m just someone who loves to work and make images. I’m an image person; moving and still. That’s really my focus. This has such a deep sense of calming for me that I have to do it and there’s no other way for me to be.

Hannah: So I kind of wanted to talk about one installation specifically, Idyllic Space. That was my favorite part. I don’t know if I’m supposed to say that. It felt so nostalgic, if not something I personally haven’t experienced. I love that you projected it on the ceiling, allowing people to sit down and experience it all, and listen to the music that goes with it too.

Tyler: The ceiling-mounted element and the kind of environmental elements—the idea that you can lay down, that we created this kind of turf, a suburban dreamland for you to enjoy the film—that all came from me thinking about the history of how we watch images and how we watch moving images. Historically, when film was first being made in the US, you would never actually put a camera below a black person’s eyes, so as to not make them look too heroic. So I’m putting [these images] on the ceiling. Basically, I wanted the viewers to [be] directly below this group of young black men in Georgia enjoying themselves. That in itself creates a relationship between the viewer and the subject or object on the screen. That already goes against the historical elements. When you think about films like D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation and so on and so forth, and the earliest films that were made, they were never going to depict a black person in this way. That’s why you see the images of my friend Celine tricycling on plexiglass directly above the camera, or another friend of mine, we call him E.A., eating this strawberry ice cream cone and that ice cream is dripping down onto the screen. You feel this direct relationship, being below these men and looking up to them as heroes, but also laying back and dreaming and letting the images wash over you.

Hannah: I think that that’s a very visionary aspect that hopefully we see more of. I also wanted to ask about the purpose of screen printing on different fabric and the importance of the clothing line.

Tyler: When I started taking pictures, because I was a film student first, the most practical thing in small apartment spaces was working with fabrics. I didn’t have the money to get big seamless backdrops from the camera stores and I also found the color selection very limited. So I started to work with fabrics from the garment district as my natural backdrops for portrait shoots. I found the textures to be more dynamic and the color possibilities to be more wide-ranging. That just became a natural characteristic in my work going forward as I started to think about that choice more critically. On a subconscious level, I was really drawn to the pictures of Gordon Parks. When you see those Harlem families you already think of the laundry line that they’ve used for their laundry that week or that day. When you see his segregation story pictures of the South, you see a woman laboring and putting clothes and towels and her family’s bed sheets on the line. Then I started to really think about the laundry line as a poetic symbol; an allusion to the working domestic black body, but also to the fact that our lives are tied to these fabrics. And also my images use the fabric, so I wanted to then put the images back onto the fabrics.

Hannah: Yeah, I like that idea of putting it back on the fabric. There’s like one shot where someone’s playing with linens and I saw you then put it back on the same sheet.

Tyler: Exactly.

Hannah: Is there anything about the show that you want to comment on that I haven’t asked about?

Tyler: Just that I’m excited about this chapter of my work because it’s been something that’s been culminating. It’s been exciting to work commercially and do magazine shoots and do shoots for brands and fashion houses that I love—I’ve always been drawn to these ideas of fashion and identity through dress. Then to take those ideas and those characteristics and the things that I’ve been working on and simmering on for years, to put them into a physical space—it really is like my universe is splattered onto all the walls in this museum.