‘Off the Wall: American Art to Wear’ remembers the woman-led rebellion against social conformity and the elitist art establishment.

In the early ’70s, an art history student named Julie Schafler Dale admitted to herself she didn’t want to be an academician. She wanted a career in the arts that was more hands on, that would allow her to engage with the vivacious arts of her generation; she wanted to focus on something new, young, and exciting. Dale, who had a longtime interest in the art of body adornment, approached the American Craft Council with a pivotal question: were there any artists using clothing to express themselves? They gave her access to slide files and catalogues of work made by artists across the country who were painting and sculpting with fabrics and fibers, and using the body as armature.

“I thought I had died and gone to heaven,” Dale recalls. Though the pieces were wearable, it wasn’t fashion. It was wearable art, an entirely new form pioneered by a generation who came of age in the ’60s and ’70s. “It was made by people who had something to say, who cared about the world around them and who were trying to make a difference,” says Dale. “The idea was to get art off the walls and out of museums and into our daily lives”.

Immediately after her discovery of this “national body of handmade, one of a kind clothing,” Dale knew her next step. She opened Julie: Artisans’ Gallery in 1973, on the corner of 62nd street and Madison Avenue. Now a beacon of corporate chains, fast fashion, and luxury brands, it’s difficult to imagine that Madison Avenue was once an epicenter of art, fashion, and culture. Knowing there was no existing market for these works, Dale chose a location with as much visibility as possible, to let the market define itself.

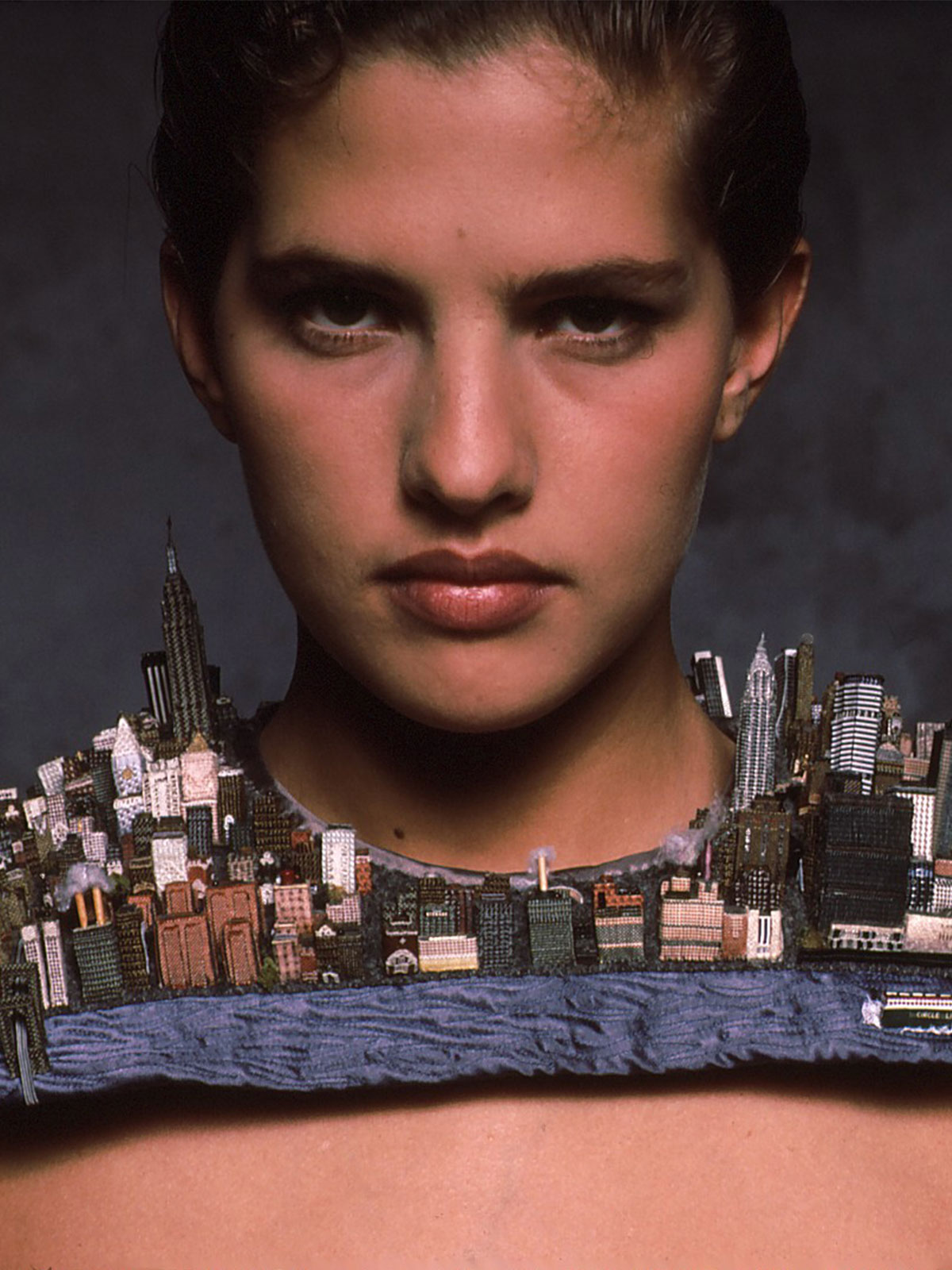

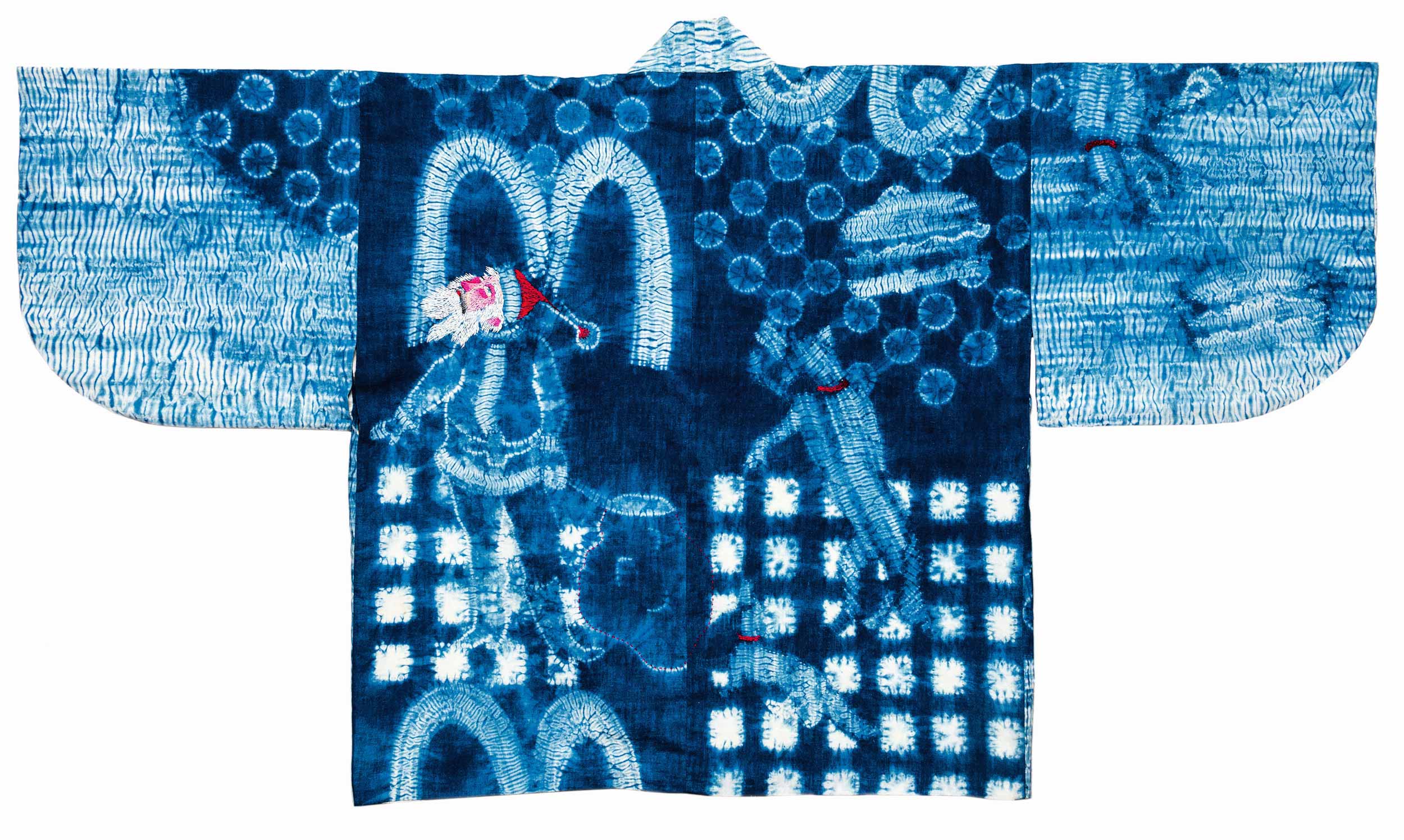

Dale says the work shown in Artisans’ Gallery was “kaleidoscopic in its visual range.” Each piece was made with painstaking processes, over the course of months or years. Dip-dyed silk and crocheted kimonos hung from the walls next to custom capes, sculptural coats, and elaborately adorned masks. Here, garments were canvases, and artworks could be animated by the body. “Every day was like Christmas. People who I had never laid eyes on before came in with black garbage bags and out came these extraordinary things,” says Dale. “My mandate was: do the piece you always wanted to do, not the piece that’s going to sell tomorrow. The priority was totally reversed.”

Her 13-by-30 foot space served as the premier destination for wearable art for nearly 40 years, making Dale a trusted collector, cherished patron, and figurehead of a movement. Despite a hugely influential run, Dale was unable to continue operating the gallery after her lease expired in 2013. “It was as much a lifestyle as as business, and all of those people who were my extended family for many years, I lost touch with.”

But this fall, the many faces and colors that characterised Artisans’ Gallery converged again at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, for the opening of a monumental exhibition that was over 12 years in the making. Off the Wall: American Art to Wear features over 100 wearable artworks by over 60 different artists, many of which were gifted by Dale. “It was a very unusual and emotional opening. There we were all together again, reunited with each other and many artists were reunited with pieces they made up to 40 years ago. It was like a time warp.” A show of this scale feels like a watershed moment for the discrete American art movement, which has been chronically overlooked and underappreciated by historians and critics.

“People just don’t understand it,” says curator Philadelphia Museum curator Dilys E Blum. “It’s always been thought of as clothing and wrapped up with fashion, but that was not the intention. It’s very much about the times and how artists thought of themselves and the environment and politics of the world they lived in,” says Blum. In the world of wearable art, “Fashion” is its own kind of f-bomb. While the question of whether fashion is art has long plagued the world of haute couture and the fans of brands like Comme des Garçons and Alexander McQueen, in the wearable art movement, there is no oscillation. It’s art, that happens to be wearable.

Blum worked with Dale to create an exhibition that contextualizes the artworks within the counterculture of the ’60s and ’70s. Visitors are guided not by a timeline, but by a series of era-defining songs. The art is grouped into themes based on tracks like Bob Dylan’s “These Times They Are A Changin,” The Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations,” and Earth, Wind & Fire’s “In a Land Called Fantasy.” In a projected montage, footage of San Francisco’s Summer of Love in 1967 flashes between protests and allusions to the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy. The Vietnam War is very much the elephant in the room, which adds weight to the use of the corporal body as a vehicle for expression in a time when matters of survival and mortality were centerstage.

College campuses were instrumental in breeding youth and subculture of the ’60s and the atmosphere at the Pratt Institute was no exception. In 1968, five of its students—Janet Lipkin, Marika Contompsis, Jean Cacicedo, Sharon Hedges, and Dina Knapp—taught themselves how to freeform crochet and revelled in its potential. Cacicedo is quoted in the exhibition book Off the Wall: “Pratt was a Mecca for exploration. The counterculture of the era was embedded in our philosophy, our attitudes, our dress, and our enthusiasm to be different in our art making.” Lipkin also explains, “We were in prime time: 1968-1970. That’s when everything was exploding. Discovering yourself was the most important thing in the universe and we were at art school, so anything that was unusual, new, or inventive was supported.” The so-called “Pratt 5” went on to become some of the most recognized names in the movement, and as regulars at Dale’s gallery, their work is well represented in the show.

In the white, male, highly conceptual and elitist art world of the ’70s, the use of a ‘domestic’ craft was its own kind of rebellion. The mostly female artists making wearable art were daring to revive the importance of handiwork and ancient techniques, and blurring the lines between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture. Dale writes in the exhibition book that these baby boomer artists were “free of the drive of their upwardly mobile parents for security and stuff and the pressure to conform to traditionally structured society.” Museum visitors are reminded that the psychedelic, rainbow palette and other bits of hippie iconography (butterflies, tribalism, organic forms) that run throughout the show were very intentional rejections of the cultural sterility, restrictions, and contradictions of the Eisenhower era. “Self expression was a driving force, the catalyst for pushing through new frontiers, fueled by a sense of empowerment and the realisation that individual stories were unique, relevant, and worth telling,” says Dale.

Pieces on display vary dramatically, from a jacket encrusted with 25,000 gold safety pins by Mark A. Mahall to Bill Cunningham’s feathered “Griffin Mask.” Though there is no uniform aesthetic, there are recurring topics, like environmental concern and sustainability, new age spiritualism, and tributes to ethnographic or indigenous works. It’s clear that each work is a kind of a diary of a moment in the artist’s life, and that each object is an extension of the individual. “Every one of those pieces has a personal story, and as you dive in you realize how intimate they were and how the cathartic the journeys were in terms of creativity. They are chunks of a lifetime,” says Dale.

The exhibition does a wonderful job of reconstructing the vibrant atmosphere of Dale’s Madison Avenue gallery. And in asking what wearable art is, it leaves visitors with a different question: why doesn’t anyone know about it? Wearable art is a culmination of things not traditionally taken seriously by the art world: it’s craft based, women led, and rooted in counterculture and non-western aesthetics. The Art to Wear movement refused to align itself, and in many ways actively rejected, the successful and trending (read: commercial) works of its time. Maintaining integrity can often mean sacrificing visibility. Fortunately, Off the Wall is now carving out the practice’s deserved place in history.

“Off the Wall: American Art to Wear” is on view at the Philadelphia Museum through May 17.