In his new exhibition ‘The Stillness of Life,’ the revered photojournalist reconciles with his legacy of capturing war and destitution, by turning his lens to the English countryside.

“I feel like I owe something to Somerset,” says British photojournalist Don McCullin of the county he first encountered as a child evacuee during The Blitz, Germany’s bombing raid against the UK during WWII. “This is my spiritual home… my psychiatrist’s chair.”

One of the most significant photographers of the last century, McCullin is best known for his harrowing black and white record of humanity at its most desperate and depraved. Shell-shocked US soldiers at The Battle of Huế; mass starvation in Biafra; victims of cholera in Bangladesh; homelessness in Aldgate—McCullin has witnessed unimaginable bloodshed and horror on almost every continent, reporting from hellish places with photographs that grab you by the collar and don’t let go.

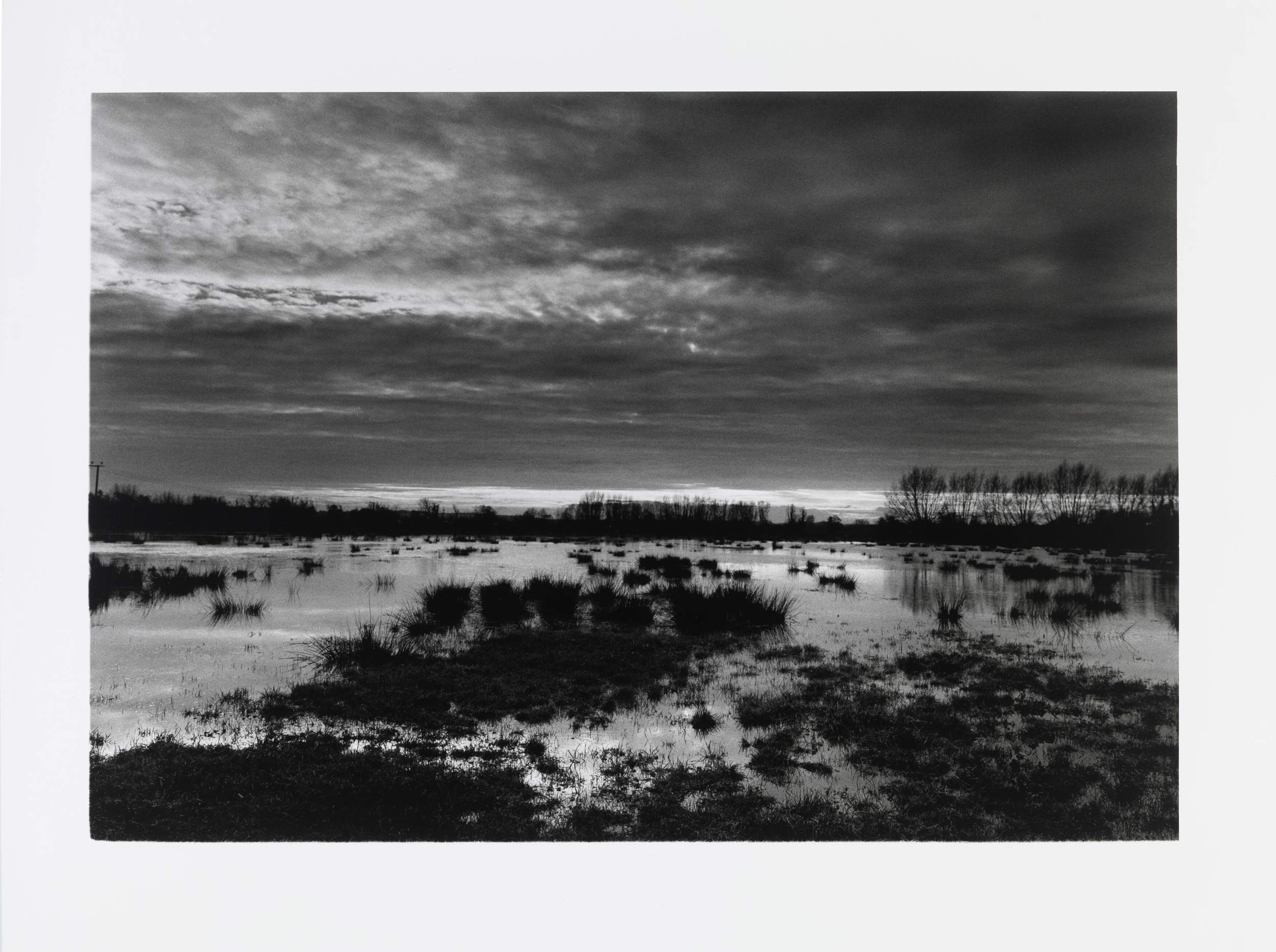

In between assignments, McCullin would return to his stone cottage in Somerset, the purchase of which, some 30 years ago, he describes as, “The best thing I ever did.” High above the surrounding valleys he works in solitude, re-printing old negatives during the summer months spent in his darkroom and photographing the landscape in winter.

“I only take pictures in the winter because the skies are much more expressive. When the light’s like this,” he says, gesturing to the overcast sky. “It makes it easier when you’re printing because there are no shadows. I’ve got a picture from Vietnam of some men running with a body. He was with me, this guy, when the grenade went off—he got most of it and I got hit with all the stones—but in the background there’s a big white pole standing in a garden where the battle was and every time I print that picture I worry about having to print it in.”

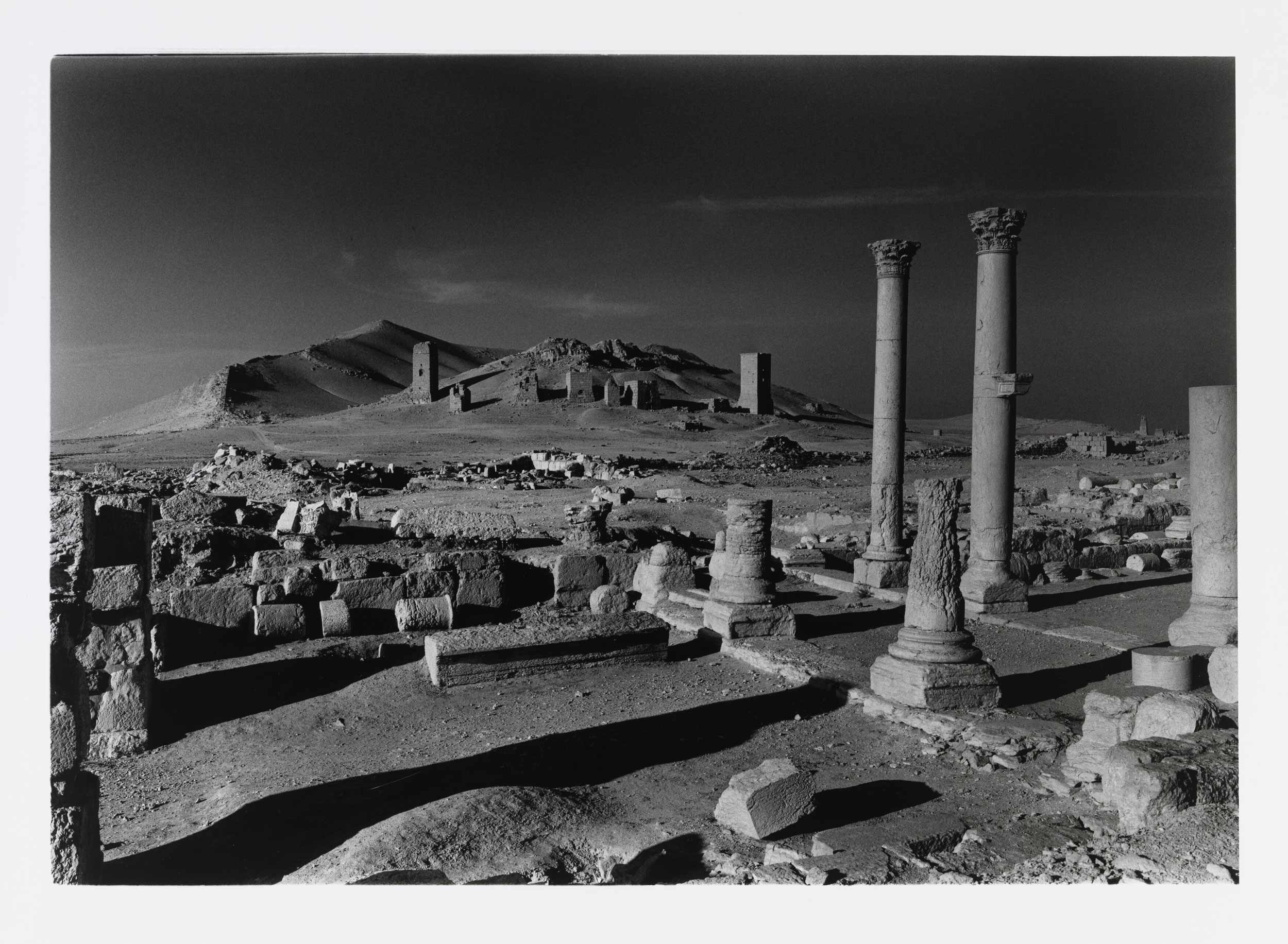

His latest exhibition at Hauser & Wirth Somerset, The Stillness of Life, reveals what has soothed the mind of a man who has seen so much—not just brooding compositions of neighboring fields and meditative still lifes—but travel photographs from Hadrian’s Wall, Palmyra, and most recently the Arctic. Unlike his conflict photography, these photographs were taken as an urgent means of self-preservation, with virtually no people, yet with unmistakable traces of the ghosts he tries so hard to exorcise. “I do this voluntarily,” he says of the landscapes. “No-one asked me to do it, no-one pays me to do it—it’s me that makes myself do it.”

Often referring to the English countryside as his greatest salvation, the works on show, some taken in the weeks before the exhibition, are testament to his extraordinary energy and continued sensitivity to darkness, both literally and metaphorically. Despite his modest claims that he “left school with no education to speak of,” his landscapes consistently reference the formal language of classical painters, while his tendency to accentuate threatening skies speaks of his Wagnerian sense of drama. “When I look at the sky I see the paintings of [John] Constable,” he says. “He did a series of skies on small canvases, so the first thing I do when I wake up in the morning is look at the sky and think, ‘Is there a possibility I can make a landscape picture today?’ Of course some days there is and some days there’s not.”

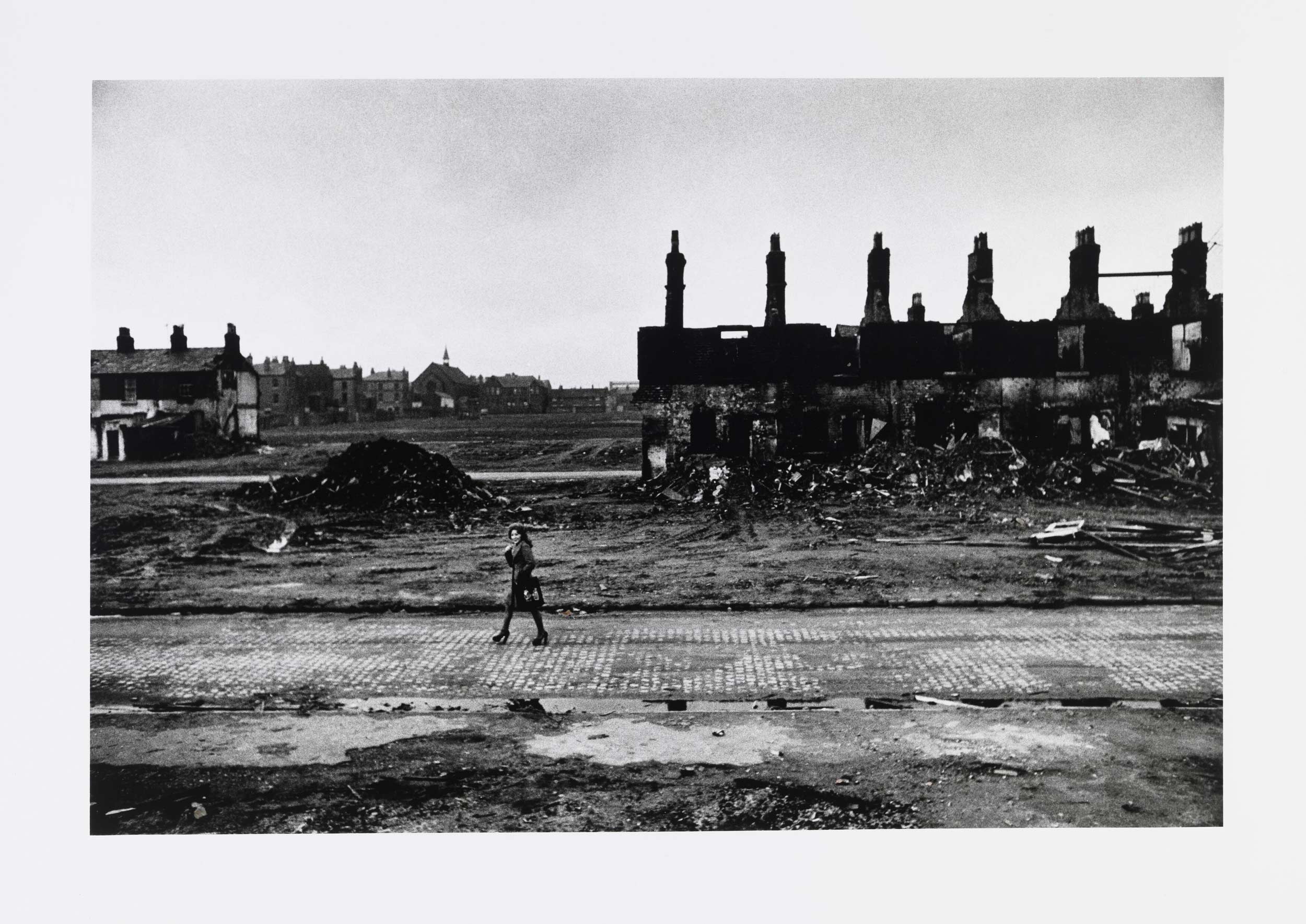

At 84 years old, the run up to this show has seen McCullin tirelessly pore over old negatives in the hope of producing a better print than the last—his collection of over 60,000 photographs is ordered by this standard. Pointing to one of his industrial landscapes taken in the 1960s of a father and son passing through an apocalyptic scene of derelict housing in Liverpool, he says, “I made that print a few weeks ago. I always jumped on [the negatives] I thought were the best and pushed a whole swath aside, so now I’m looking at them and thinking. Time helps the negative. It’s like laying wine down, you can look at a picture that’s taken in the ‘60s and it looks as if it were taken 100 years ago. I dug out a bunch of pictures from Liverpool because of my exhibition [McCullin’s Tate Britain retrospective will travel to Tate Liverpool this June] and I’ve been finding pictures I never bothered with. But they are just as important.”

Just as he is constantly looking to perfect his craft, McCullin has found himself still wrestling with the guilt that has dogged his conscience since he first pointed his camera at the misfortune of others. “I don’t think I’ll ever resolve it,” he says. “I think it’s impossible to resolve because you’ve accepted the laurels. I’ve always thought though, all the prisons I’ve been in and the beatings I’ve had, the hospitals I’ve been to and the blood I’ve seen coming out of me, that’s been my monthly payment to the guilt. But it’s still there.” A quick look at his recent work proves as much. Far from a parochial, tourist board-approved image of Somerset, McCullin’s vision carries the darkness that is so much a part of him, transforming muddy plains into Somme-like battlefields and naked trees into ghostly blasted stumps.

Extraordinarily, for a photographer as revered as McCullin, he bears a genuine sense of conflict regarding his legacy and contribution. “I don’t know why I haven’t been attacked more in my life, verbally or in print,” he says. “I’ve been to all these wars and revolutions and you make a name for yourself covering other people’s misery. I couldn’t really have stuck my head out any further, it would have been chopped off, but people tend to be quite kind to me.”

Without a hint of bitterness, he recalls taking part in a BBC film last year, during which an engineer refused to participate because of the objections he held towards McCullin’s work. He is even less certain of the impact his work has had, despite the enormous success of his Tate Britain retrospective last year, adding, “I never thought what I did in my life has made an iota of difference to the way the world has moved on. Every time you get rid of one war another one pops up. I think sometimes I feel I’m preaching to the converted.”

The solace he has found in photographing landscapes and nature has partially helped alleviate that uncertainty, just as it has helped reconcile the trauma and anguish. On several occasions during our conversation he refers to the pride he feels for these photographs—unlike his conflict images, many of which he no longer looks at, buried as they are deep in his archives. Above all though, there is still a strong sense of the tenacious photographer who dropped everything to photograph the Berlin Wall in 1961, who risked life and limb to show horrors that might otherwise not have been seen, and who still looks for any excuse to return to his darkroom. “When I was young I didn’t know anything about photography but I quickly started learning. I never got big-headed about it because I had so much to learn. I still feel the same, I don’t think I’ve arrived, I don’t think I’ve finished the journey.”

“Don McCullin: The Stillness of Life” is on at Hauser & Wirth Somerset through May 4, 2020.