Boxing, voguing, and en pointe ballet—Behind her legendary Performa collaboration with artist Cecilia Bengolea.

On a recent Saturday afternoon in SoHo, a line forms outside Jeffrey Deitch’s Wooster Street project space, curling around the edge of Canal Street. It is the closing weekend of Performa 19, the eighth edition of New York’s performance art biennial which, dedicated this year to the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus school (the first to categorize performance and theater within the umbrella of visual art), saw live happenings pop up in venues across the city throughout the month of November. As visitors shuffle into the gallery, they gather around assemblages of plush fabrics, arranged sparingly across the floor like a sand-and-stone garden; meanwhile, two boxers spar in an enclosed vestibule above. When the overhead lights dim to illuminate the fabric sculptures with halogen spotlights, a rasping laughter pierces the quiet.

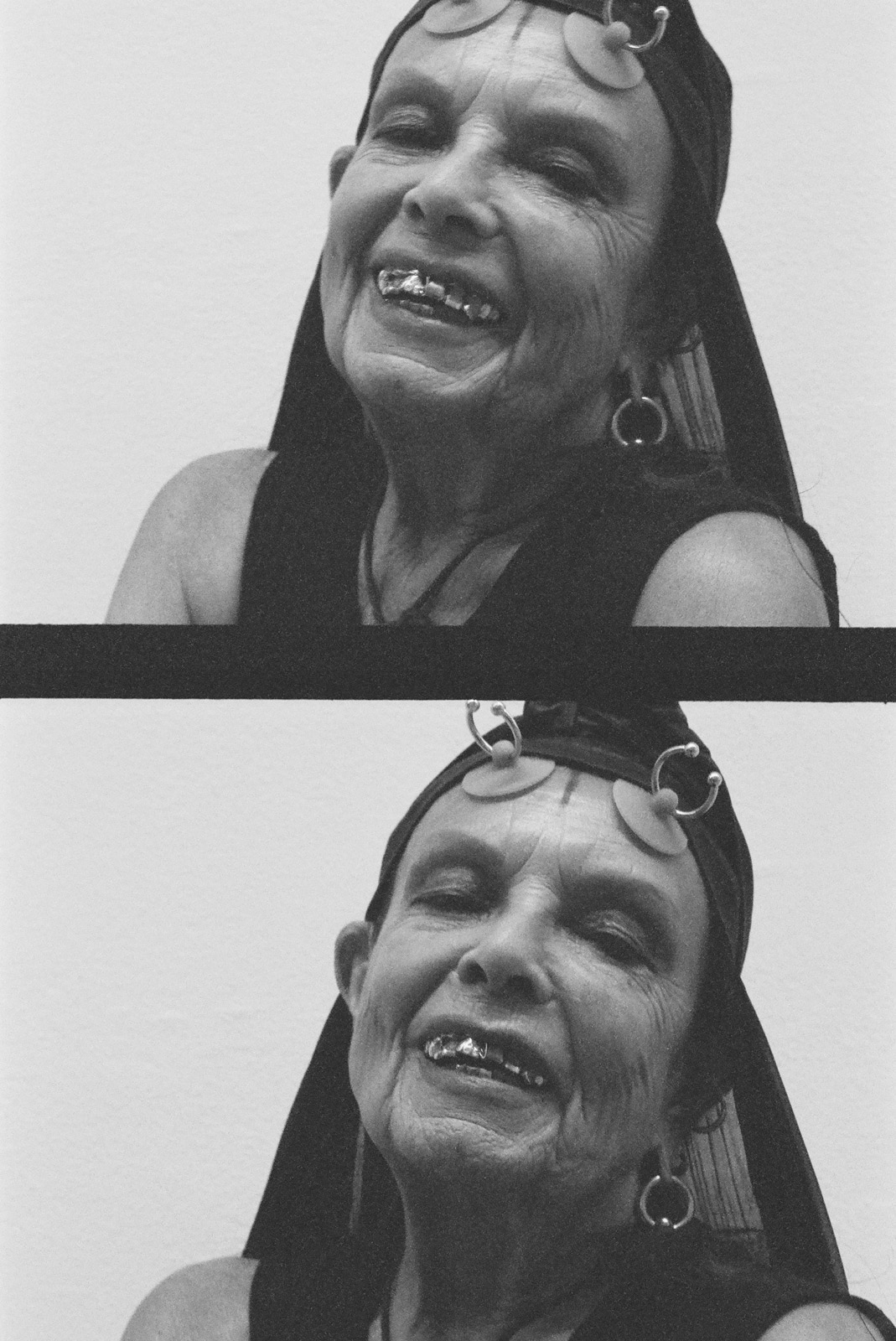

“Sit. Dream. Dance,” the voice murmurs repeatedly, bitingly, rumbling over a gooey noise track by the band LAVASCAR. It belongs to Michèle Lamy—she of the golden teeth and dip-dyed fingernails; the black-haired smoker and matriarchic muse to many, none more famously than her longtime counterpart, Rick Owens—who weaves through the crowd until she reaches the center of the room. Lamy, wearing sky-high platform boots and a short dress designed by Owens, walks hand-in-hand with the Argentina-born, Paris-based artist Cecilia Bengolea, known for staging harrowing performances in which bodies are imagined as “animated sculptures.” Bengolea fumbles behind Lamy, her form obscured beneath a bulbous sheath with a tentacular protrusion emerging from its chest.

Fans of Japanese designer Rei Kawakubo will recognize the garment from Comme des Garçons’s Fall 2015 runway presentation, though this particular item is typically tucked away within Michèle Lamy’s personal archive, which exceeds 50 unique Comme des Garçons showpieces accrued over the last decade. Lamy and Bengolea, who met in Paris, dipped into the closet to outfit a troupe of 10 dancers—and a few audience members, including curator RoseLee Goldberg’s young grandson, who posed in a towering Spring 2014 sheer mesh and velvet number for an impromptu photoshoot following the show—for the debut of this collaborative performance, commissioned by Performa and titled “Before We Die.”

Following an introductory pas de deux between Bengolea and Lamy, the dancers enter, lifting the textile heaps from the floor and placing them atop their frames. Viewing the scene, as they begin to dance, feels like examining the shifting shapes of a kaleidoscope: Performers from varying backgrounds—boxing, ballet, dancehall, ballroom—move, contort, and struggle under the structural, constrictive costumes. The dancer Quenton Stucky shuffles beneath an enormous neoprene coat featuring a cut-out porthole that reveals his bare chest; meanwhile, Honey Labeija, a Brooklyn-born voguer from the House of Labeija, catwalks freely across the space in a Spring 2014 shift.

If nothing else, the performance is “expansive,” as Bengolea describes it, with works of various media melting together to actualize a singular cacophonous composition. And though Bengolea’s choreography divides the show into a narrative of three acts, overall, the movements appear instinctual, raw, though dictated in part by the constraints of the costumes. Clothes, Kawakubo and Lamy would agree, are objects like any other. “Dancers always want to feel free and show their body,” Bengolea says. “And none of the costumes allowed this.”

Lamy, who departed for London shortly after Performa’s finale, reflects.

Coco Romack: You recently debuted your collaborative performance “Before We Die” with Cecilia Bengolea, and it was interesting just to see dancers moving, or struggling to move, in such dramatic, structural Comme des Garçons pieces.

Michèle Lamy: That was the challenge, for a dancer to have that heavy costume to carry on their body, but I think that was what made it so special.

Coco: It was especially wild to see those pieces dragged across the floor.

Michèle: I thought it was nice to start with the clothes on the floor, as the sculptures that they are, and then put life into them. It was important to me that the dancers were putting them on in front of everybody. Rei knew that we were doing this, though I don’t think I will send pictures.

Coco: How did Rei react?

Michèle: Well, we don’t know. I just know there was not a no. Now she is designing the costumes for the opera ‘Orlando’ that is going to premiere in Vienna. We are going with Rick on the 8th of December, and she’s definitely much more into this. When it is time, I will show her but, until then, we had an okay.

Coco: You own over 50 Comme des Garçons pieces, including many iconic runway pieces from the last decade. How did you select which garments to pull from your collection?

Michèle: This summer, I had all the clothes brought to my house in Paris. I put them on Cecilia, and both of us were playing with the clothes. When the garments were sent to New York, I was with Rick in Los Angeles, so they started the styling and casting before I arrived. When I came in, I saw the dancers had a tendency to try to put the less heavy pieces on. Even for Cecilia, there were some of the pieces that were a little less taxing to get in. I thought it was not really the story, so I challenged the direction.

Coco: What do you love most about Comme des Garçons?

Michèle: It is a love story that began when I moved back to Paris and started going to her shows. To me, it’s art. I have a collection because you collect an artist. They are beyond clothes, it’s difficult to say that they are clothes—they are sculptures that are made to be on a body. If I could have them all, I would. It’s just I have to choose. When I got the idea that they could be in a performance, I thought this was the reason I was collecting.

Coco: How did you meet Cecilia and come to collaborate?

Michèle: Like most of the things I’m doing, she asked for it. I got a text from her late last spring, saying that she was going to do a performance and asking if I wanted to participate. I Googled her, and then I remembered that I’d seen her perform in Gstaad in 2017, where there were performances outside in the snow. So I knew who she was, and I said yes.

And then she heard the music that I’ve been doing with the band LAVASCAR. She chose some of the music, some pieces, and then we worked on it to make it to go with our performance. All the dancers came four days before the show and she choreographed on the spot. She is herself an amazing dancer so, to me, it was a performance, but a lot was said with dancing.

Coco: How would you describe the music you make?

Michèle: Hip-hop slam with a very slow voice.

Coco: What do you listen to while you work?

Michèle: I always listen to music, whatever I’m doing. Mainly techno.

Coco: Cecilia said that, when preparing for your show, the two of you slept overnight on a beach in Deauville together.

Michèle: You never know what will put you in a creative mindset. We became friends and wanted something to do. This summer I was in Paris a lot because I was working on that performance and on the furniture collection I was doing with Rick for a piece we did at Centre Pompidou.

But then we were in Paris, and Cecilia was in Paris. And this is one of my things—sometimes we were fucking dying of heat this summer—so I said, okay, let’s all get in the van, we can sleep on the way. Of course when we get there, it’s totally raining and it’s dark and the ocean is big. That’s the thing I like to do, that we loved to do together. So, we were not preparing for the piece, but we were hanging out.

Coco: What do you do when you procrastinate?

Michèle: I smoke. But I smoke a lot more than I procrastinate.

Coco: You and Cecilia both had leading roles in the performance, alongside numerous other dancers from varying backgrounds. What does your role say about you?

Michèle: I was a troublemaker, in a way. I was not in Comme clothes. I was one of the voguers, and my laugh was my vogueing. It was amazing how everything worked together, those clothes with the movement, and I thought I could bring some kind of humor to it—doing a little dancing on one foot in the middle of those dancers. I wanted to have this kind of element.

Above the performance, there was a mezzanine that was empty. I don’t like when there’s something empty, except for somebody doing the lights, so I thought, let’s bring in some more boxing. So I thought, with those vogue guys, it would be fun to be hanging out up there. While people were showing up, we also had the element of those funky fights up there.

So this is that element I was bringing to it—this is that bubble of art, or of saying something in a different way, but being in conjunction of what we usually do.

Coco: Who do you look up to?

Michèle: I love Björk, but I don’t listen to her music too much. I like the idea of her. And Laurie Anderson. I like the cabaret-style of things, too. I think it’s about time I realize I like mixing strip tease with the voice.

Coco: You and Cecilia have both spoken openly about having worked performing strip tease. How does sexuality tie into your art-making?

Michèle: I don’t think that strip tease is especially sexual. It’s about expressing yourself, having fun, playing with your body—it’s mainly for yourself. But perhaps we are just exhibitionists.

Coco: “Before We Die” explored tropes of destruction, serenity, and pleasure. What, if you could, would you destroy in the world today?

Michèle: Guns and pistols.