Mikhaile Solomon's PRIZM returns to Miami Art Week, providing artists of the African diaspora a platform to exhibit their work without restriction.

While contemporary culture is slowly starting to recognize the necessity of inclusion, inclusion has yet to become normal. A rising issue that has accompanied the art world’s newfound embrace of diversity is that artists who have historically been excluded from the predominantly white European market are only becoming included for the primary “function” that their identities serve. To be political, disruptive, exciting, exotic. It’s a pseudo form of inclusivity that invites these artists to the table—but to the kids’ table adjacent to the main one.

This absence of genuine representation of artists from African or the diaspora in the art market inspired Mikhaile Solomon to found PRIZM, an art fair that exhibits work from contemporary artists of the African and the global African diaspora to represent the full range of their experiences.

“The art world forces an invisible contract on African and diasporic artists,” said Solomon. “Often, the work that is vetted and accepted by in the wider global market has a limited scope—it is racially focused or can be so self-effacing that we don’t really see where the empowerment exists for people of African descent.”

PRIZM has been forging this necessary space for the past six years and returns to Miami Art Week this year with its seventh edition Love in the Time of Hysteria, an exhibition featuring work from over 39 artists and an international roster of galleries. The exhibition considers how our relationships with love, compassion, and respect evolve during times of social chaos.

“[In] our relationships with each other, we only atone for our poor treatment of each other when there is limited time left,” said Solomon about the exhibition. “What if we just collectively decided that we were going to find a loving and respectful way to deal with each other and our environment?”

This is a powerful theme that the artists in the exhibition consider in their work, which range from paintings and mixed media collages to photography and intricate ceramic weavings. Document caught up with three artists from this year’s fair—Evita Tezeno, Jared McGriff, and Anina Major—to talk about their art practice and the freedom of making art without restrictions.

Kaylee Warren: You create these gorgeous, whimsical images that you say are meant to provoke laughter and to help enrich the soul. How has whimsy played a part in your work?

Evita Tezeno: I believe that this world is so dark and so dreary sometimes. We have so many misfortunes in our lives, and I create a bit of an oasis. A small oasis amidst a storm to combat all the negative things that go on in our lives. So when you come to my artwork, you feel a breath of fresh air.

Kaylee: You’ve also said how you have been inspired by images you see in your sleep that you translate in your work.

Evita: I was painting Impressionism back in the ‘90s. I’m a Romanticist, and I believe that Impressionism is very romantic, but it still wasn’t going anywhere [for me]. So, I had a dream that a mysterious man came to my door and said, ‘I am a messenger from your father.’ I said, ‘My father? You know Earl Tezeno?’ And he said, ‘No, silly, your heavenly father.’ He said, ‘take these images, and said if you do these images you will be successful.’ So, I started to do these sketches that I had in this dream. This was in 1989. The next year, I got a call from the owner of the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival who said, ‘I saw some of your work and would like you to submit some work for the Congo Square poster.’ I showed [the work] to him and got it. I was the first female to do it.

Kaylee: You’ve been a working artist for 25 years now, having become represented by six galleries and selling work to international clients. How does it feel to finally be showing your work on a platform like PRIZM?

Evita: It feels like a fairytale. Ever since I was a young child, I wanted my artwork to be celebrated. My [family] wanted me to be in the medical field, or a teacher, and I told them, ‘No, I want to be an artist.’ I told them I will be an accomplished artist one day. Just watch. And I never gave up. It is a dream come true.

Kaylee: A question that’s popped up in the art world over the past few years is whether or not Black artists can make non-Black art. Considering your deep connection with fairytale, what do you think of this question of whether Black people can make art that exists outside of their identity?

Evita: My work is about emotions. And emotions have no ethnicity. So my figures may represent my Blackness in all the different hues I use in my work, but still people of all ethnicities see my work and they can identify with it. Sometimes, I’ve listened to non-brown people say, ‘Oh, Black work is so controversial. It intimidates me.’ But I just had a showing at my studio, and I had mostly caucasian Americans come, and they were all piled in my studio, gathering around my work saying, ‘Oh my goodness, I feel so much joy, I am so happy!’ And this is what I try to convey in my work. I want to bring joy, I want to bring happiness.

Kaylee: I was reading about how the spaces that exist between our vision and cognition and further themes like spontaneity inform your art practice. I found that so fascinating. I’m curious if you could expound on that a little more.

Jared McGriff: That’s key to the work I create mainly because the work I create is spontaneous. I don’t believe in the compositions for the painting or things like that. Everything generates from this idea that if you enter your unconscious mind, it will tell you a story about the things that don’t really register necessarily in your conscious mind.

Kaylee: What drew you to watercolor specifically?

Jared: I’m not a trained artist, I don’t come out of art school or anything like that. So studio practice just started with documenting the way I obsess. I draw obsessively. I started doing painting in sketchbooks, and watercolor was a really easy way to work in that format, quickly and to get the ideas out and have some of these qualities that kind of capture the ephemeral nature of space and the individual in space.

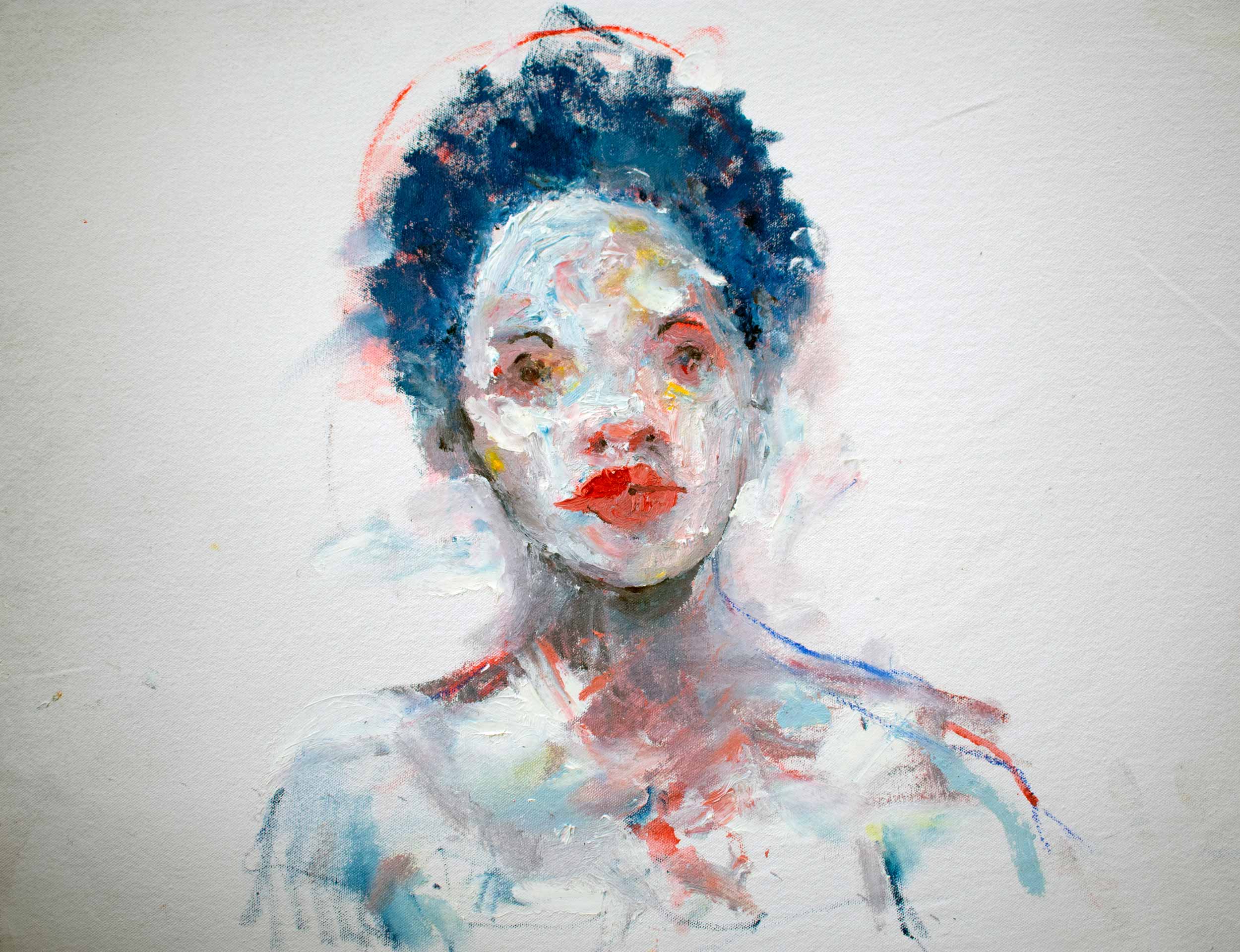

Kaylee: I was particularly drawn to the figures in your paintings. In some of them, you can’t even really see their eyes, which abstracts them. These figures are frequently depicted in domestic spaces, as well. Who are these people?

Jared: As someone who’s really fond of abstract ideas and paintings, I think that with the figures there’s a kind of unknown about the individual. In societies, when groups of people come together, there are often certain people who are particularly silenced, who aren’t as prominent as the dominant culture. [I try to convey ideas around] abstracting these histories and things we take for granted as our sensory pool of how to navigate the world. The individuals themselves, they are imagined people. [I’m] abstracting the [domestic] space and making it something that’s not necessarily one person’s place but a place that could belong to others as well.

Kaylee: What are your thoughts on the question of whether or not Black artists can make non-Black art?

Jared: That one’s tough. The short answer is: yes. My work is not Black, but it’s Black at the same time. I am Black as a creator, so that in and of itself, makes it Black. My work is going to reflect my Black American experience. But, I don’t think it’s necessary for me to stylize my work or position it in a way to where it says this is Black. It’s odd. I think, overwhelmingly, what I want my work to do is to spark those conversations and to build more empathy in the world. If it inspires people who have a particular agenda or end, that’s fine too. But my goal is to work on these ideas and explore them fully.

Kaylee: As a ceramicist, what initially drew you to clay?

Anina Major: First of all, I really like it. [Laughs] Basically, you can make anything with it, but as I developed my relationship with the material, [I began realizing] it has this lasting quality so it’s able to deliver a sense of permanence and at the same time still offer enough room for fertility. There’s a long history with this medium, and conceptually that is what attracts me to it. The history lends itself to the dialogue I am trying to have with my work.

Kaylee: That relates to a line I read from the core of your practice, which is the relationship between self and space as a means of cultivating moments of reflection and acceptance. I found this to be really special and important.

Anina: I’m originally from the Bahamas, which is where I was born and raised. For me, there was no escaping how the actual place, the actual location I was in had an influence on thoughts of self and what it means to belong. When I left [the Bahamas] for school [in America], I was at a point where I was spending a lot more time in the United States, so it started becoming a form of home. I started to think about how that influenced my idea of belonging and what are the things that make us feel like we belong to a space or a community. My work is really just parsing through those experiences and trying to find these connections, whether that’s through objects or through an actual activity such as weaving.

Kaylee: How do you feel your work is relating to the themes of love that inform this year’s exhibition?

Anina: I think about how easy it is to lose oneself in a time like this. I think about activities I can engage in that can keep me connected to the things that I’m proud of, that contribute to this world in a positive way. I think about our ancestors a lot, I think about what it means to love oneself and love and embrace one’s history and how we can use that in a very empowering way. I think the spirit needs healing and it also needs strength and it also needs grace. These are the things I think about when I engage with weaving.

Kaylee: What you say about self-love in particular really hits home for me with how people of the diaspora are simply seeking to find love in this time of hysteria, as the exhibition calls for.

Anina: Oh, agreed. And finding ways to connect, finding ways to have kindred experiences with each other.

Kaylee: What are your thoughts on the question of whether or not Black artists can make non-Black art?

Anina: I think that across the African diaspora, we are all connected. I think we have a shared history, and there’s some kindred energy in us. But, I also find the term Black art to be a bit restrictive. We’re all navigating the world with individual histories that contribute to our voice, whether it’s art or music or writing or math. Yeah, I’m Black. Quite proud of it, nothing wrong with it. It gives me a unique voice, and I think part of that is because we don’t have enough of our voices. The range, as far as I’m concerned, is still very restrictive. One of the things I like about PRIZM is you have a myriad of voices coming together, and as we expand our definition of Black and what it means to be of the African diaspora, I think we will start to have less and less of these questions.

PRIZM Art Fair takes place at the Alfred I. Dupont Building in Miami through December 8, 2019.