The artist meticulously documented the influential art school, but while her male cohorts became legends, her work was misappropriated and forgotten.

What if you were a woman and your life’s work was stolen from you and credited to a man? In 1933, Hungarian-born Jewish photographer Lucia Moholy was forced to flee Berlin after her then-partner, communist politician Theodor Neubauer, was arrested by the Nazis. She was forced to leave behind 600 glass negatives that documented the Bauhaus, placing them in the care of her ex-husband, artist and Bauhaus master teacher László Moholy-Nagy. When Moholy-Nagy had to leave Germany, he left them with Bauhaus founder and director Walter Gropius, who eventually had them sent to Chicago after he arrived in the United States. In 1938, Gropius used around 50 of Moholy’s precious negatives to create photographs for the Bauhaus exhibition, and its catalog, at the Museum of Modern in Art in New York, not crediting her once. Moholy got wind of this and wrote letters to Gropius asking for her negatives back, but he refused until she got a lawyer involved, and finally, in the late ‘50s, Gropius begrudgingly sent Moholy her negatives, with several of the fragile glass negatives damaged.

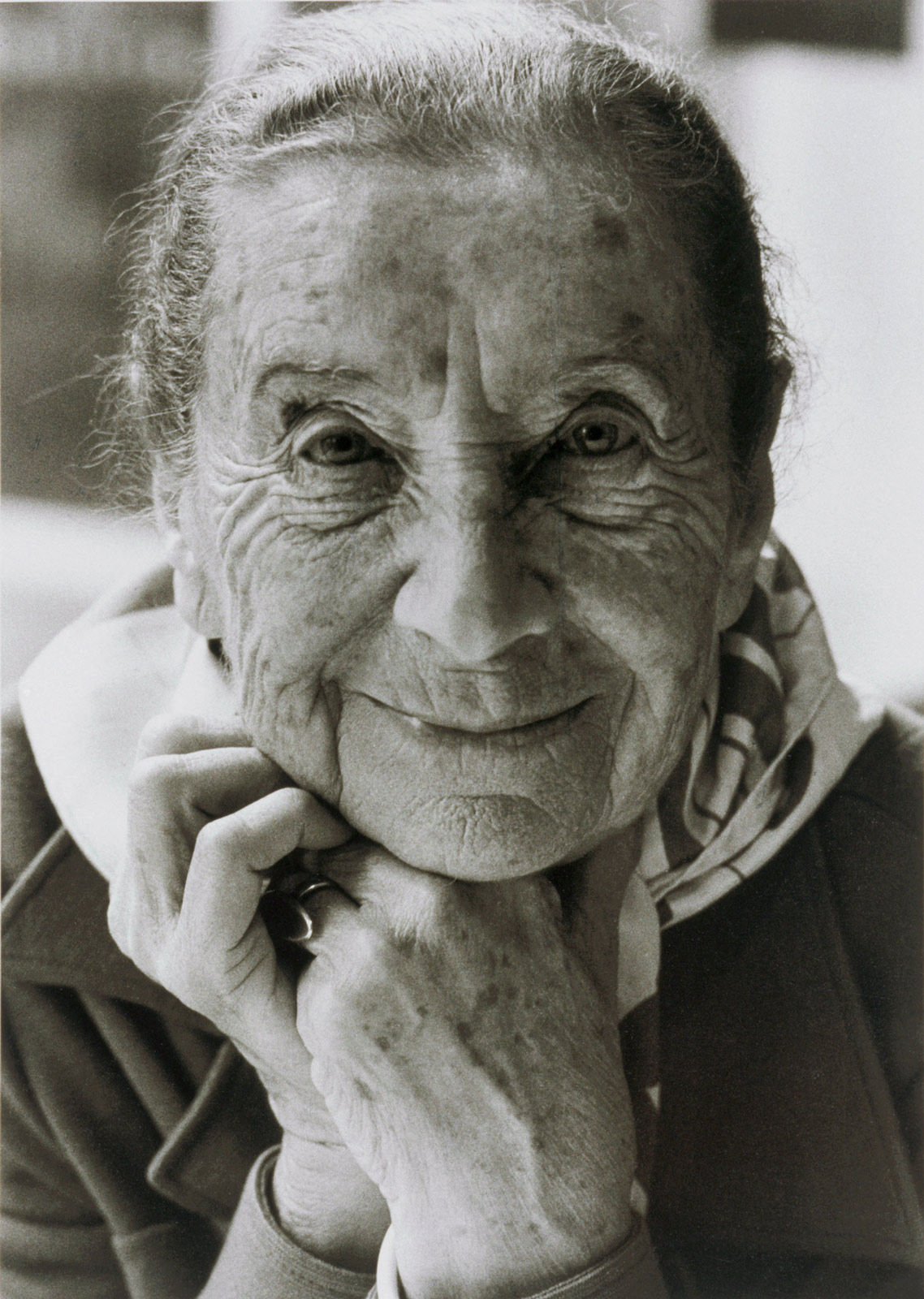

Moholy is finally getting her due at Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Germany until February 2, 2020, in an exhibition titled Lucia Moholy: Writing Photography’s History. The show traces Moholy’s career, and her impact on the Bauhaus and photography, from a pioneering photogram she created with her husband and the photographs she took while at the Bauhaus—which include three vintage prints recently acquired by the museum—to the 1939 book she authored, Hundred Years of Photography: 1839–1939, up until her death in Zurich in 1989. With the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus underway this year, it’s about time that the women receive the credit for their talent that was often overlooked because of their gender.

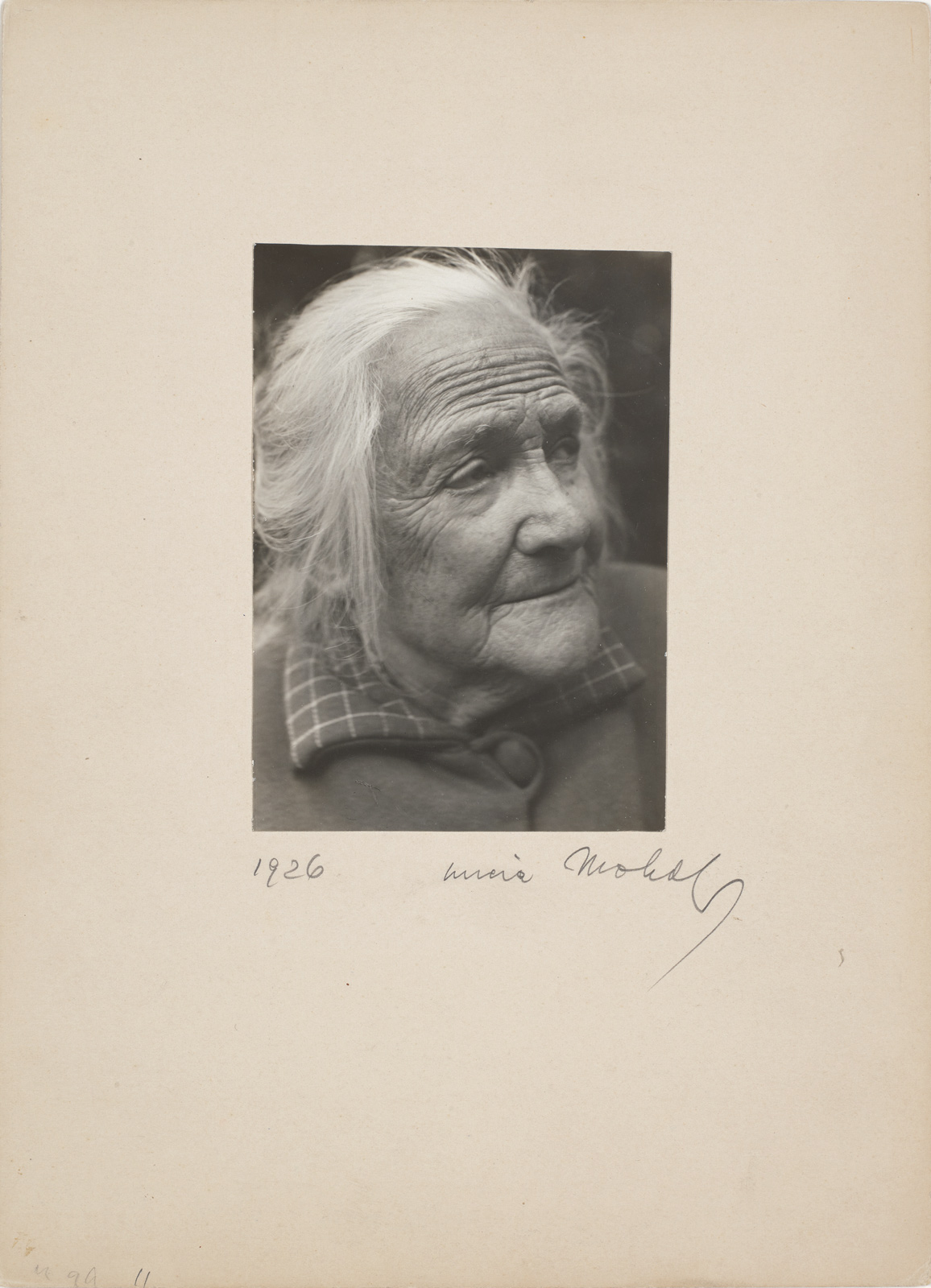

At the height of the Bauhaus in the ‘20s, Moholy was better known as Moholy-Nagy’s wife rather than as a photographer in her own right. Moholy’s work preserved the history and legacy of one of the most influential art schools, yet during her lifetime, the photographer seldom got the credit she deserved for documenting the Bauhaus. While at the school with Moholy-Nagy in Weimar from 1923, and in Dessau from 1925 to 1928, she toiled away in the darkroom as Moholy-Nagy’s primary darkroom technician, and she also collaborated with him on his art, but the credit usually went to Moholy-Nagy. Moholy meticulously photographed the school and everything about it, from the interior and exterior of its iconic Dessau building, to its students and faculty, and the work they created. The cosmopolitan Moholy felt trapped and isolated in the remote Dessau, writing in her diary in 1927, “Dessau was like a place where you travel, miss the train, and are forced to wait for the next one.” One of her black-and-white photographs depicts the minimal masters’ homes on Ebertallee, with trees—that she could have erased with a simple retouch—resembling the bars of a jail cell. During the couple’s final years with the Bauhaus, Moholy she pleaded with her husband, telling him that if he wanted their marriage to survive, they would have to leave. They returned to Berlin together, but the move couldn’t save their marriage and they parted ways in 1929.

Although the school touted itself as an institution that promoted equality between genders, and was one of the first art schools that admitted women, they were often relegated to disciplines like weaving. “There were great, creative women working at the Bauhaus, but they didn’t have official functions, or they were trapped into the weaving course, because that’s a typical ‘feminine’ material,” said Miriam Szwast, the photography curator at the Museum Ludwig.

After Moholy fled Berlin and the Nazis, she spent time in Prague, Vienna, and Paris, before landing in London in 1933. Her ex-husband tried to get her a job as a lecturer in Chicago, where he lived after leaving Europe, but Moholy’s visa request was denied. She microfilmed publications in British libraries for UNESCO in 1940. Then, an opportunity to help establish libraries and archives in Turkey brought her to Istanbul and Ankara in the early to mid ‘50s. She relocated to her final home in Zurich in 1959, working as a critic for The Burlington Magazine and publishing Moholy-Nagy: Marginal Notes. Towards the end of her life, Moholy finally started getting recognition, when the first monograph of her work was published in 1985.

Moholy’s images captured the geometric lines of a 1929 opera set by Josef Hoffman, a now-iconic tea set by Marianne Brandt, and the masters’ homes—which have since been rebuilt and designated a UNESCO heritage site—that were bombed and destroyed during World War II in 1945. Without Moholy’s photographs, the Bauhaus’s identity would have lived on solely through the memories of those who lived through it, and the art, design, and architecture that was born from it.