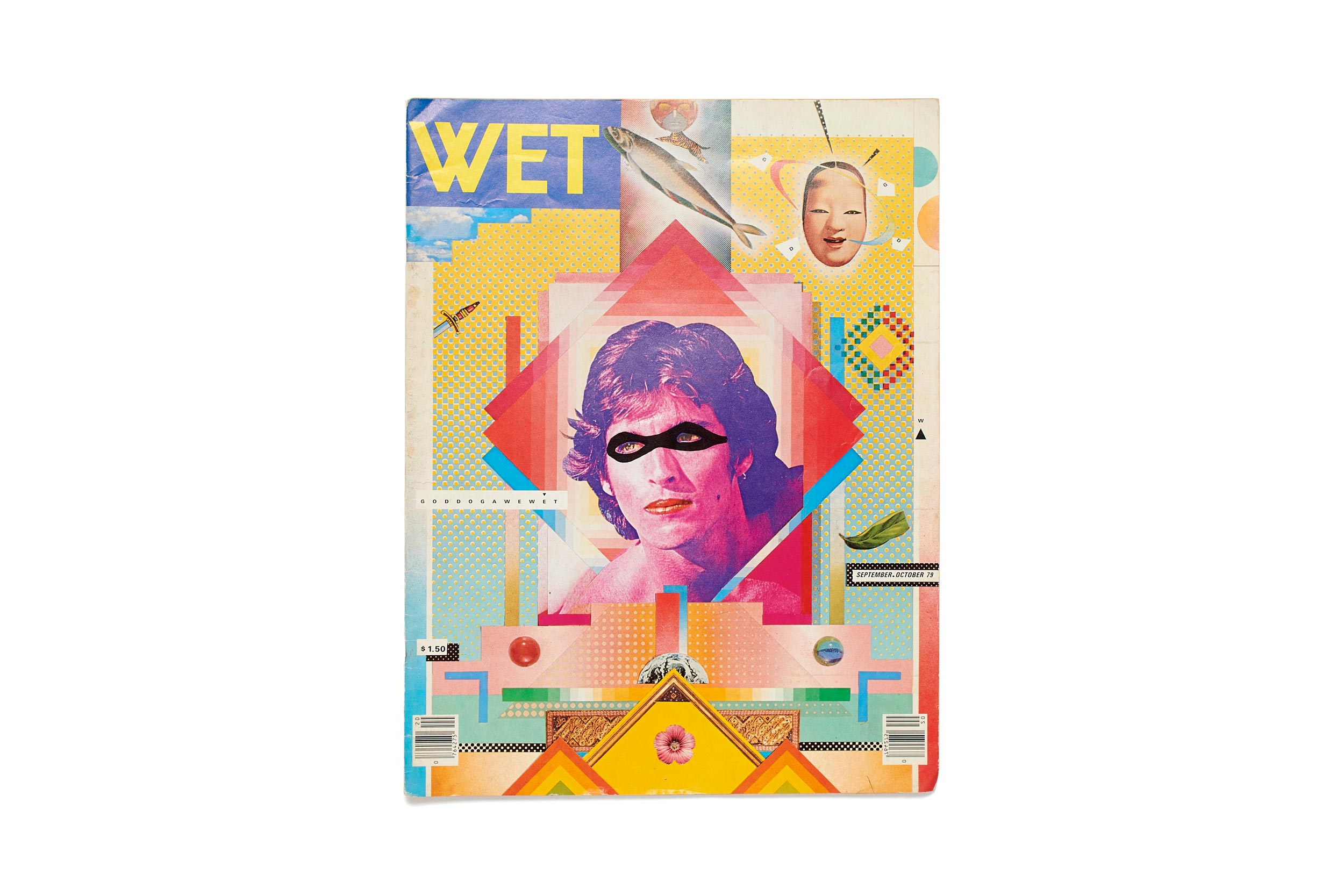

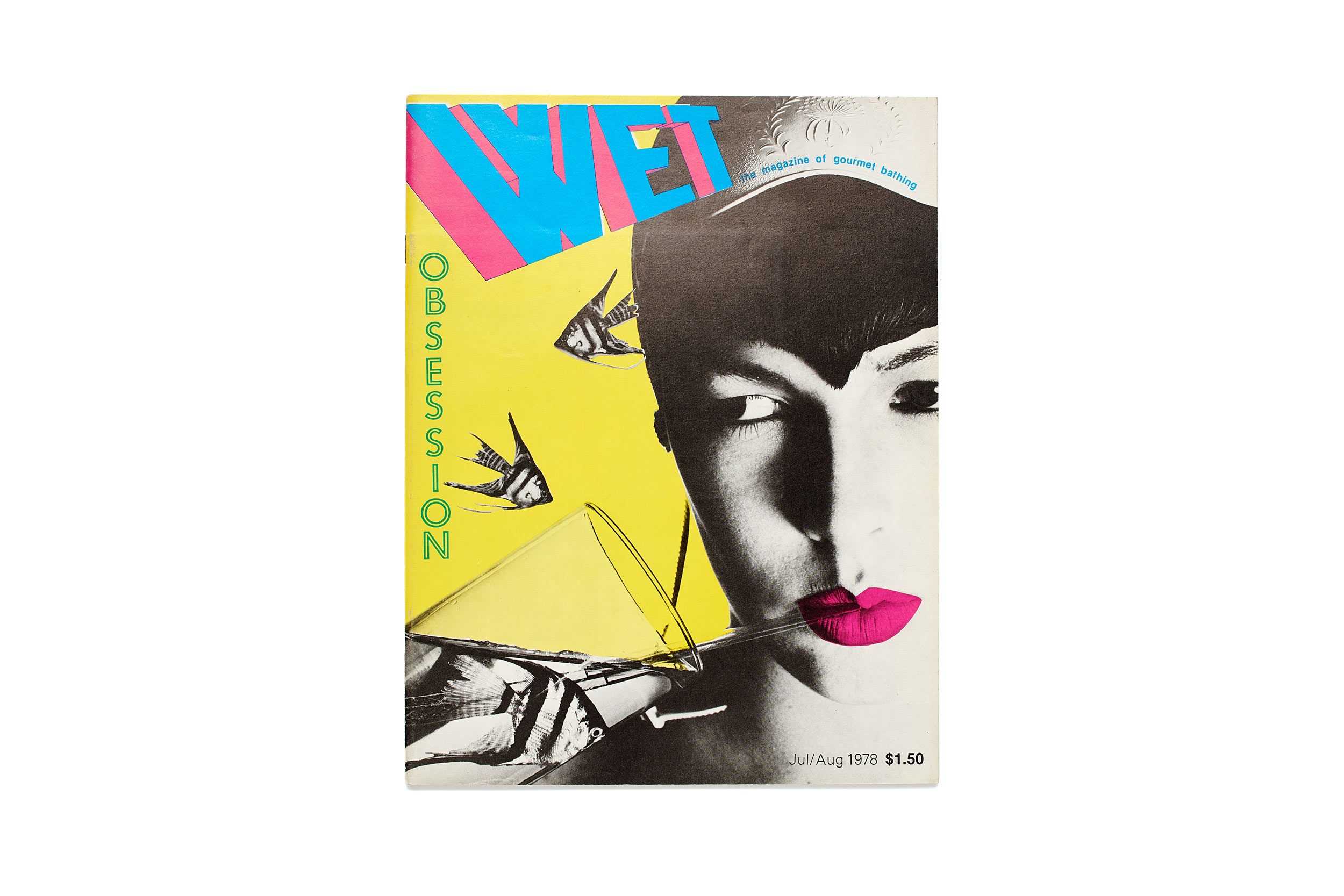

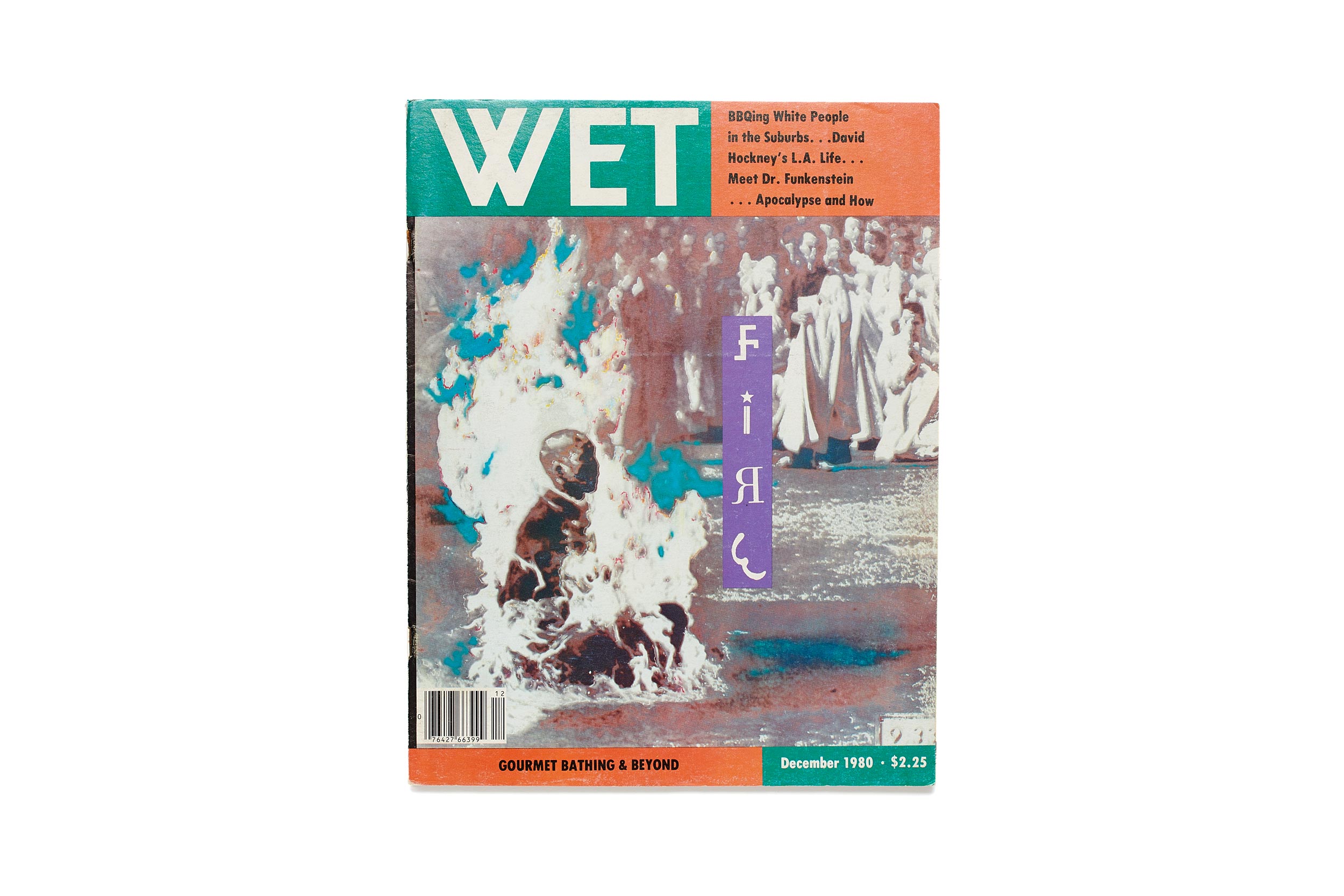

We revisit the oddball ’70s magazine, which counted Debbie Harry and Mick Jagger among its cover stars, for Document Fall/Winter 2019

Leonard Koren put out the first issue of Wet: The Magazine of Gourmet Bathing in Venice, California, in 1976. Just 600 copies, and skimpy. “I was ecstatic nonetheless,” he writes in Making WET, his book about the five-year experience. “I rode my bicycle around Venice and shoved copies into the mail slots of everyone I knew. The response was generally appreciative, but there were also instances of acute mystification. ‘Why would anyone possibly want to make a magazine about g-o-u-r-m-e-t bathing?’”

Good question. Koren was an architecture grad at UCLA but had dropped any notion of pursuing it as a career, and was making what he called Bath Art. That meant persuading individuals, mostly fellow artists, to get naked and bathe in water, in mud, in steam, or just in hot air, while he photographed them. He would turn these into artifacts through various printing techniques and sell them in galleries or by word of mouth.

The models had worked for free, so Koren decided they deserved payback—namely, a party as artfully put together as his prints. It was held at a Russian Jewish bathhouse and made such a splash that the Los Angeles Times gave it a column and ran a photograph of Koren greeting a guest, the designer Rudi Gernreich. This was celeb-consequential. Gernreich’s career firsts had included the thong bathing suit, the bathing suit without a built-in bra, and the monokini (a bikini minus the top). Koren had made the charts.

“How, I wondered, could I exploit this unexpected turn of events?” he muses in his book. “My brain was on overdrive. In order to slow things down I would draw a hot, steamy bath around two or three o’clock every afternoon. Once immersed I lay perfectly still. My muscles unclenched and my eyes softly focused on a patch of mysteriously glowing water six inches in front of my nose. During one of these quiet moments an almost-audible voice whispered into my ear, ‘Why not start a magazine about gourmet bathing?’”

Those almost-audible voices can really screw up sometimes, but this one had it nailed. The second issue, dated Aug/Sept 1976, was a 16-pager, and the magazine swiftly evolved into a fairly fat bimonthly, known both for its po-mo eye and a voice that earned it a loopy cool cred—less cosmic than hippiedom, less ornery than punk, so let’s call it New Wave. Wet was off to the races.

In his book, Koren cites Vogue, Gourmet, and Andy Warhol’s Interview as role models of sorts, but you would not have known it. Full-length Q&As were rare and the visuals were quirkier, some the work of young hires like Thomas Ingalls and April Greiman, others from known offbeat talents like the photographer Jacques-Henri Lartigue, who sent in a shot of a mustachioed man afloat on the water wearing a suit, tie, shades, and a UFO-shaped hat.

“It wasn’t trying to be Playboy or a skin magazine, but it treads into that area almost accidentally.”

Gary Panter, who would go on to do the sets for Pee- wee’s Playhouse, contributed a painting, Gators. Matt Groening came up with Forbidden Soaps, a suite of drawings, before Life in Hell, and way before The Simpsons. Larry Williams did a cover shot of Debbie Harry, here formally called Deborah, aiming a six-gun at the reader. There was a double-page of 60 men and women wearing bathing caps, some accessorized by sunglasses and shots from Marcia Resnick’s Re-visions, the realized imaginings of an immediately post-pubertal girl. One image of a freckled puppet was accompanied by the words “She secretly lusted for her television idols.” Another image, this one of a group of dolls, was captioned, “She derived pleasure from dressing her boy dolls in the undergarments of girl dolls.” So, Wet was pictorially unpredictable, except that you could count on some humor, such as a bearded Ringo Starr sitting in a bath, booted and fully clothed, and Jack Nicholson, snorting, “Gourmet bathing? Do I look like the kinda’ guy who takes a bath? Shit—I don’t even drink water.”

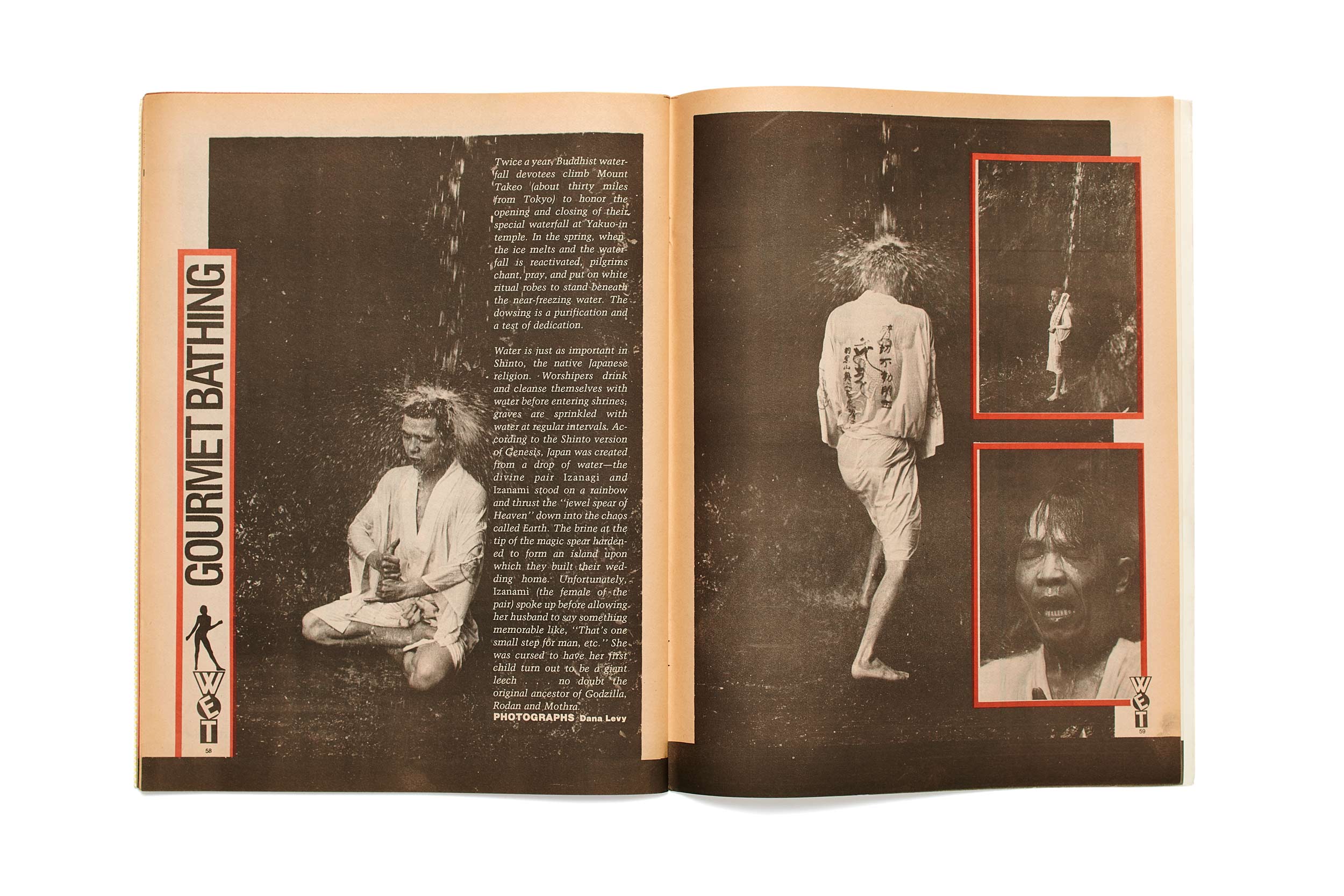

More bathing. I should make a point here. The bathroom is a core concept in Wet, but Koren’s use of the word was focused. When you hear somebody ask for the whereabouts of the bathroom, it’s not because they plan to take a bath. The Duchamp urinal is famous and Maurizio Cattelan’s fully functioning 18-karat gold lavatory bowl made an impact when it was installed in a Guggenheim bathroom, but I know of few major works of art in which an actual bathtub plays such a central role. In 1498 Albrecht Dürer made a woodcut in which Saint John the Evangelist is shown in the bath, but this is because an executioner is drenching him in boiling oil, an image which made it into Wet. The most famous bathtub painting is surely The Death of Marat, a 1793 canvas by Jacques-Louis David, which depicts the firebrand of the French Revolution after Charlotte Corday stabbed him in the tub. A somber, forbidding tub it is, too. Modern plumbing awaited the attention of Wet.

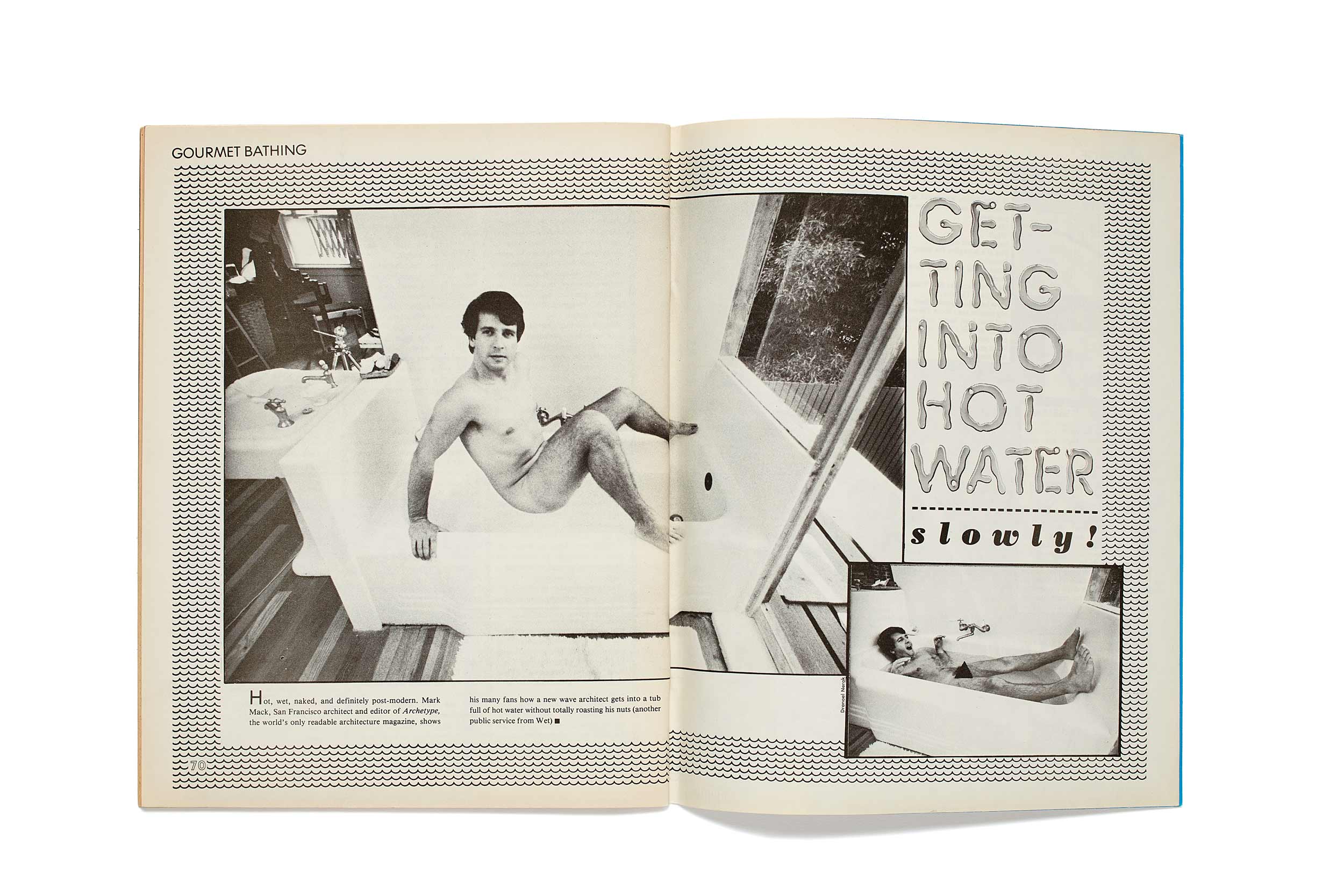

There were two iconic shoots, Koren says. “One is 23 Beautiful Women Taking a Bath. It’s different women taking a bath in the same bathtub individually. It’s put together in kind of a wonky way. They all use the environment of the small tub in a slightly different way. And that was what I was looking for. The counterpoint is 17 Beautiful Men Taking a Shower. Each person showers in a distinctive way. And I turned that into a fold-up book that extends into a long panorama.”

Another point. “The Pubic Hair Papers,” a piece of mine, which ran in Rolling Stone well before the launch of Wet, looked at how Penthouse and a slew of mags were trying to outdo Playboy. Anybody hearing of a magazine featuring youthful nudity would likely assume that Wet was of their number. Wrong. “We skirted the line. When you have naked bodies, there is an undeniable erotic energy,” Koren says. “But it was never soft-core. There was a little bit of spiciness, a little bit of charge. It wasn’t trying to be Playboy or a skin magazine, but it treads into that area almost accidentally.”

Wet’s bodies tended to be shot avant-garde grainy rather than centerfold glimmery, and the women were not all centerfold cutie-pies, but there was more to the mag than naked bodies. Like clothed bodies. As one leafs through the issues, names and faces bob up, with memories attached: the Jim Carroll Band, with Carroll’s druggy hit, “People Who Died”; Eve Babitz, the author of fictive memoirs who is now experiencing a renaissance; the Kipper Kids; and, inevitably, Timothy Leary. I went to a party at Leary’s in L.A. back then, over-celebrated, lost a favorite shirt to a grabby girl, napped, grabbed a handful of biscuits in the morning and wolfed them down on the way to my New York flight which took a detour through the Milky Way. Those biscuits! Was the Wet interviewer at that same party?

Here’s Kenneth Anger, a maker of dark short films, gay when that was still illegal, deeply involved with the occult. Anger had fled California for London because one of the actors in his movie Lucifer Rising, Bobby Beausoleil, was furious with him and had joined the Manson group. Here is Anger on the subject of LSD. “All this mystical bullshit about it, that it was dangerous,” he says. “What isn’t? I mean, even hair dryers are dangerous.”

Wet was good for such quotes. Nico of the Velvet Underground, asked if she had ever made a record with commercial marketability in mind, snapped back, “I made a single once with Jimmy Page, but it was a failure both artistically and commercially. Page’s music was like cement.” Jimi Hendrix surprises with the revelation that “I patterned my style after Dick Dale.” That would be Dick Dale, King of the Surf Guitar. “I don’t listen to nuthin’,” Captain Beefheart says. “Bob Dylan impresses me as much as… well, I was gonna say a slug, but I like slugs. But Johnny Rotten. He’s a big fan of mine. I used to see him out in the audience in England and he’d stand up and holler. He’s funny. Smart too, and a nice guy.”

Here’s Elio Fiorucci, who had launched in Milan in 1967 and then opened a New York outlet in 1976 with a party at Studio 54. The store was hotter than hot when he spoke with Wet two years later. “What do you think will happen in fashion?” he was asked. “My theory is that fashion will end,” Fiorucci said. “There will not be any more of what we now call trends. Trends are very reassuring. They exist because they are reassuring. One thinks: I dress so-and-so because everybody dresses so-and-so. Maybe someday people could just wear what they like.” Maybe someday. Fiorucci went into receivership in 1989.

Another observation. Studio 54 had opened the year before the interview with Fiorucci, and disco was global, ubiquitous. I have not read every issue of Wet, but I’ve read many, and I didn’t see much about disco. The mag does reference punk, but casually, as when a photo of David Johansen, taken before he performed at the Whisky in West Hollywood, noted that he was “formerly of the New York Dolls.” The July/Aug 1978 issue, the theme of which was “obsession,” ran a cheerfully nasty drawing, a Punk profile by the line artist, Natali, captioned STUBBLE on chin, DOWNRIGHT DISGUSTING hair, SLY APPEARANCE. This was totally Wet. Print media, from The New York Times to the tabs, like to bring back information from frontiers of intense public interest. Not Wet. Its frontiers were oddball, peculiar.

Five years is a short span to track cultural changes, but they can be spotted in Wet, if sometimes through their absence—like AIDS, still a few years away from darkening that fun in the sun. Celebrity culture was not yet an industry. Wet covered it as freaky fun. “Divine descended from the scarlet Caddy convertible with the panache of a hefty Bardot,” ran one item. “He was resplendent in a black Lurex miniskirt, his platinum hair reflecting the neon signatures of Fiorucci’s. Ironically, though, the androgynous star of John Waters’ films Female Trouble and Pink Flamingos (the longest-running film in L.A.) had difficulty out-dressing the crowd of adoring fans.” This was shortly followed by: “Imagine Cheryl Tiegs vs. Jesus Christ. Fighting it out in a boxing match.”

One change was in everybody’s face. Or out of it. Smoking had only recently been recognized as potentially lethal. But, like any dangerous sport, that made it a usable metaphor. Here’s Leonard Cohen talking about a new amour. “People in the liquor store actually pop-eyed and double-took as she went by,” he exulted. “I’m going to start smoking again. I want to die in her arms and leave her. You need to smoke a pack a day to be that kind of man.”

Over to David Hockney, to whom Wet spoke soon after his arrival on the Left Coast. “Do you jog and all that?” the magazine enquired.

“No, I just smoke,” Hockney said. “I only started smoking last Christmas and I feel a hundred percent better. Even my work is better since I’ve taken up smoking.”

I have never smoked cigarettes and tend to walk around smokers as though they were swinging plague bells, but when I interviewed Hockney a few years back, he was still aggressively puffing away and looking as full of beans as ever.

The once potent subject of mankind’s journey into space was covered, wholly characteristically, by The Process of Elimination, a piece on how bodily functions were managed in a gravity-challenged situation. This brings me to a further observation, which is that science, seldom a presence in Andy Warhol’s Interview, let alone in Vogue, was often featured in Wet. Sometimes, as with a segment about healing waters and hydro-jet therapy, because it was bathing-connected, but often because the stories were as darkly off-the-wall as the following:

It was reported from Cape Town that Christiaan Barnard, the heart transplant pioneer, had rejected an offer of $250,000 from the National Enquirer to help with the transplantation of a human head from one body to another: “I didn’t even consider it,” said Barnard. “The idea is immoral, unethical, impractical, and of doubtful legality.”

He also doubted that the head would be able to talk, even with vocal cords, because breath is necessary for speech, which was impossible without a spinal cord.

Often the science edged close to sci-fi. A piece about longevity argued that the human life span had been just 18 during the Bronze Age but has continuously lengthened, so “death should be an option, not a necessity.” But the theme of the March/April 1979 issue was “the future,” and those pieces tended to be rather less optimistic. “Can a new electronically transmitted ‘personality virus’ be altering our brain-wave patterns… forever?” inquired one writer. They went on to predict that the US would be swept by “a whole new wave of mass delusion,” causing people to experience a zombiesque “new reality.”

The “Mystery of the Mutes” in the May/June 1980 issue plunges further into our new world disorder, examining the phenomenon of mutilations of animals, mostly cattle, in 40 states, but with “concentrations of mutilations in the vicinity of American nuclear facilities.” The writer gives one vivid example, an Appaloosa gelding, called Snippy in the original reports, later shown to be called Lady. This was on the San Luis Valley, Southern Colorado, ranch of Mrs. Nellie Lewis, who discovered her cow beheaded, with no living tissue left in the “boney-eyed skull.” Also, the ranch was “plagued by weird lights” at night for years thereafter. Indeed, “Right up until she committed suicide in 1977, Mrs. Lewis maintained that UFOs had killed and mutilated her animal.”

The story became huge. Ranchers reported finding their cattle with the eyes removed, tongue and ears cut off, sex organs gone.

Among the probers of the mutilations, according to Wet, were Ed Sanders, a former member of the Fugs, who wrote The Family, a gripping book about the Manson killings, and Bill McIntyre, who produced the Firesign Theater’s radio program. It was claimed “that there had been two thousand ‘confirmed’ and 8,000 ‘probable’ cattle mutilations.” Also, that “mutilations have occurred in almost every species of wild animal in North America. Even a pair of Buffalo were grotesquely disemboweled in their cage of the Denver Zoo.”

Many blamed the mutilations on operations of the government, who were perhaps checking that mad cow disease, a brain disease that afflicted cattle and which was particularly prevalent in the UK decades ago, was not creeping into the US. But most agreed with Mrs. Lewis that aliens were pranking us. A book published a few years back uncovered a “UFO highway” across the country. The ’70s mutilations were never truly explained and have never returned in strength, but UFOs, like crop circles, are still with us. Leonard Koren’s bathing magazine kept its finger pretty much on the pulse, so we are now, I should guess, about due for that other prediction to come true: “A whole new wave of mass delusion” and a “new reality.” I can’t wait. And maybe won’t have to.

Archival issues of WET magazine and book courtesy of Arthur Fournier Fine & Rare, LLC.