Dr. Nelly Ben Hayoun's University of the Underground offers a Master's in the Design of Experiences. After the program's first two chaotic years, Ben Hayoun gives her side of the story—and her students give theirs.

This article will appear in Document’s upcoming Fall/Winter 2019 issue, available for pre-order soon.

You think you are going for a night out. Instead you find yourself in an empty warehouse on the wrong side of town. Men, wearing black, their faces hidden, appear, and something that feels unpleasantly like the muzzle of a gun is pressed to the small of your back. One of the men is yelling at you in a language you don’t recognize, in a tone that you absolutely do. You catch the words “information” and something that sounds like punishment. You are taken (driven, then pushed, then dragged) to a big cold space, where more people shout at you about things you do not know. They say they have evidence—search records, calls made—that you were planning an attack. You cry.

You are on your way to a business meeting in an unfamiliar part of the country. At a café, you put your bag down for a second and it vanishes. Inside—stupidly—is everything. Now you have no phone, no keys, no laptop, no money, no cards. You have no way of proving who you are. You cannot get through to anyone. No one believes you. They say there is no record of anyone with your name, date of birth, or address; that you do not appear on any official database; that there is nothing to show that you ever had a job or held a driver’s license or paid your taxes or owned a passport. Nothing you are has left a trace. Even if they gave you a phone, you cannot remember any numbers. After five hours of telling the same story in the same words to different people, you stop believing yourself too. You have no identity other than your digital identity. Without that, you appear to be missing. Completely deleted.

One of these scenarios is an Experience. It’s an item you paid money for, a moment you elected to have happen to you, a thing played with a cast of actors and directed by, well, a Director. The other one was just life. Nobody got paid.

We are, we’re told, tired of Stuff. We’ve done consumption, things, objects. What we want instead is authenticity and involvement, or, at the very least, something that looks incredible on Instagram. We don’t just want to receive any more; we want a memory we can stick on the fridge door. We’d like to be able to say to our friends and colleagues not just I bought this but I did this: I did Burning Man, I did an opera in a parking lot, I had a part in the Blade Runner reboot. It could be artistic or philosophical, or it could just be a nice thing you did one evening. Either way, the aim of an experience is generally to disrupt, to overturn, to make you think again.

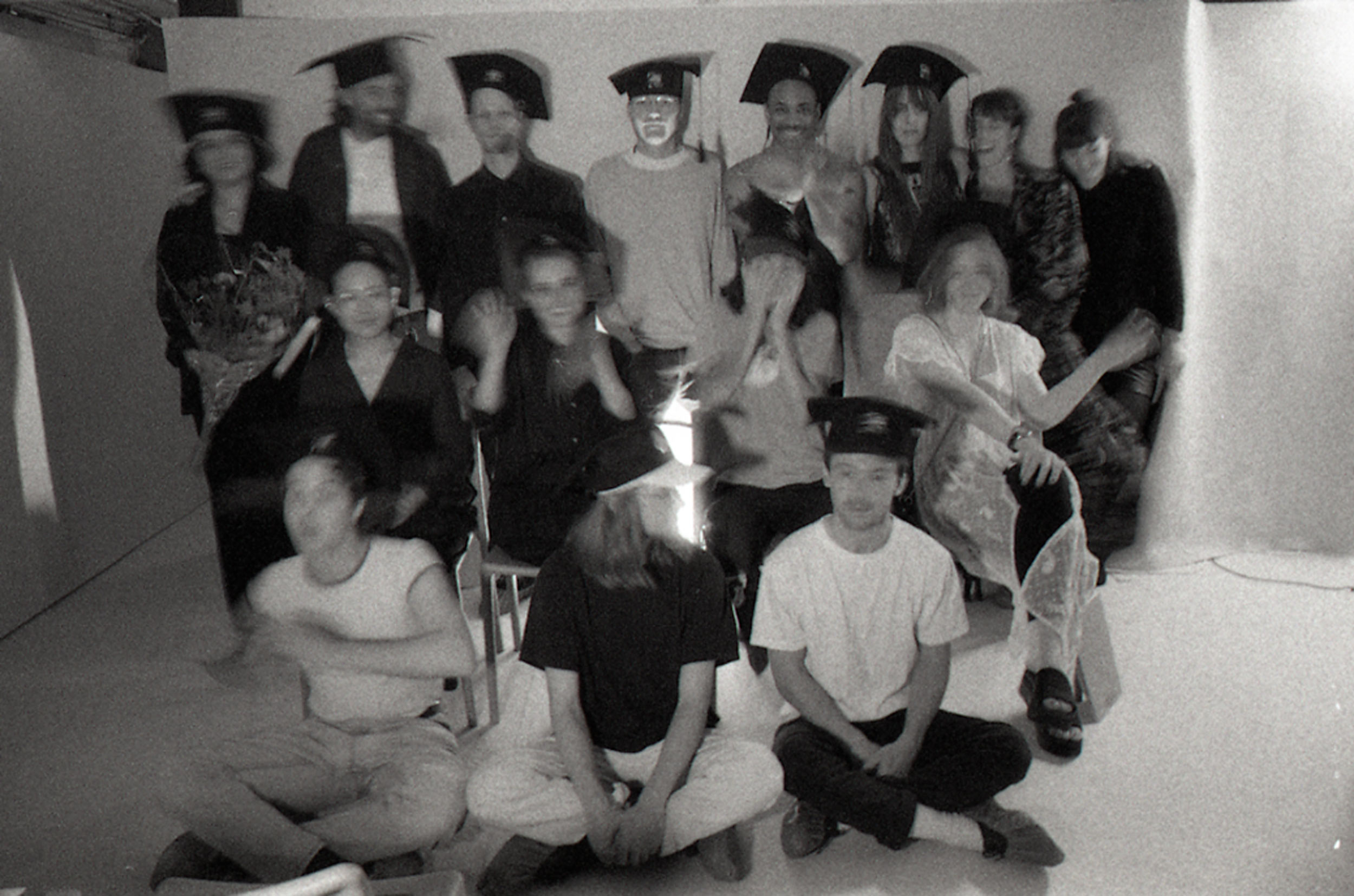

This is where Dr. Nelly Ben Hayoun and the University of the Underground come in. Two years ago, Ben Hayoun began looking for students for the first-ever “free, pluralistic, and transnational” master’s program in Design of Experiences. The course was to be run in conjunction with the Netherlands-based Sandberg Instituut and to take place in London and Amsterdam. According to Ben Hayoun, 250 students applied, from 45 countries; 15—ranging in age between 21 and 34— were admitted. In September 2017 those first students arrived in the Netherlands, attracted by the course’s multidisciplinary approach and the fact that it was free. Two years later, all but two of those students graduated.

“So was she experimenting on her students? Was the course itself some kind of staged experience? ‘Of course not!’ says Ben Hayoun.”

Those are the bits on which everyone agrees. The part in the middle is where things become more complicated. By the standards of Ben Hayoun, some of those students were good, some were bad, and some were just unbiddable. According to some of the students, they found themselves as unwitting subjects to an experiment in coercion and doublethink. They may have been designers, but they felt themselves to have been designed upon. In the end, everybody—including Ben Hayoun—got an experience. It just wasn’t necessarily the one they thought they signed up for.

To understand a bit more, you’d probably need to go back several steps to the origins of the course’s director, a woman so often called “the Willy Wonka of Design” that it now sounds like a second surname.

Ben Hayoun was born in 1985 and grew up near the Alps in Southern France in a highly politicized household. Her mother’s family was Armenian, and as a child Nelly fed on the stories of her maternal grandfather, who had moved to France with his family as political refugees of the 1919 Armenian Genocide. He eventually became the adjunct mayor of Valence—the first French Armenian to move into politics. Her father’s family was from Algeria, once a French colony, and France’s involvement in the Algerian War of Independence (1954–62) has remained a zone of silence—a silence reflected in Ben Hayoun’s family. On the Armenian side of the family, the stories never stopped. On the Algerian, nothing.

Equally crucial to her was the work of the 20th century political theorist Hannah Arendt. Imprisoned by the Gestapo and later exiled to the States, Arendt is best known for popularizing the term “banality of evil.” Less well known is the time she spent studying the psychology and motivation of the prime movers within the Nazi regime. “Everything,” says Ben Hayoun, “is informed by Arendt.”

Despite her interests in both politics and philosophy, Ben Hayoun went first into science, then medicine, then painting, then applied arts, then design. She decided to go to Japan to study kimono printing (“three granddads teaching me how to print on silk”), then turned up in London to pursue a master’s in Design Interactions at the Royal College of Arts, then a Ph.D. in geography and political theory; she then set up the Nelly Ben Hayoun Studios in East London.

Fast-forward past three feature-length films, one International Space Orchestra, several experiences which, entirely by definition, defy classification (vikings and astrophysicists in boats collecting life-forms for future space colonization, stress-testing domestic volcanoes, supersizing Japanese neutrino observatories), a set of determinedly exotic job titles (“chief of experiences” at WeTransfer, member of the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence, inspiration for her own Barbie doll and Lego figurine), plus more awards and commendations than the average Nobel winner, and you get some sense both of Ben Hayoun’s “total bombardment” design philosophy and of why her CV might include the line, “Dr. Ben Hayoun has two doppelgängers who work with her to appear at multiple places at the same time.”

As she says with some understatement, “My areas of interest are extremely broad.” In person—in all media, in fact—Ben Hayoun persuades with a mixture of fireworks, inspiration, control, and flat-out relentlessness. The description most often used about her is “force of nature.” Her experiments and experiences are on a supertanker scale. They involve scientists, astronauts, musicians, people who sew things, designers, artists—anything, anyone, as long as it shakes things up. Less Willy Wonka, perhaps, and more a kind of multiversal steamroller.

Which, of course, may be necessary qualities for setting up a brand-new “free, pluralistic, and transnational” university from scratch in two cities at the same time. Having partnered with the Sandberg Instituut and found space in a couple of nightclub basements, Ben Hayoun and her collaborators set about the creation of a course in Experience and began recruiting students through social media. “The University of the Underground lives in the undergrounds within a hidden network of urban spaces,” declared the course prospectus. “It supports forms of deviance in creativity, the non-established and the unconventional, revolutionary practices. Theatre of cruelties and musical concerts will be celebrated as we manufacture countercultures, radios, pirates utopias and experiences for power shifts.”

As promised, the course’s remit was encyclopaedic, taking in everything from AI to censorship, counterculturalism to the nature of truth—a mash-up of old-school academia, political and cultural theory, technology, opera, film, art, and metaphysics, plus guest talks from artists, musicians, activists, and philosophers, as well as collaborations with the British Film Institute and the Dutch National Opera. The curriculum was divided into conventional lectures, tutorials, and crits led by the UoU’s staff, and one-off workshops on individual subjects such as AI, often taught by outside experts. If some of the experiences seemed wacky, the academic backing was not. The course was run according to standard European Masters guidelines, the core tutors all came from reputable teaching institutions, and the students’ work was all externally examined.

If the course had an emphasis, it tilted less toward art or culture and more toward Ben Hayoun’s own political history. Its driving preoccupation was with control and the nature of the state: how surveillance works, what we the populace agree to, the architecture of technological oversight. Not so much challenging the system from without (Edward Snowden, Chelsea Manning) as overhauling it from within.

Critically, the whole program was free. The UoU’s director of operations, Chloe McClellan, estimates that the cost per student was around £12,000 (about $15,000). That includes tuition, staffing, overhead, materials, and expenses, with the students themselves responsible for all other living expenses. Around half of that money came through crowdfunding, fundraising, and charitable donations (the UoU was registered as a charity in 2017), and the rest was gathered through donations from companies including WeTransfer (with whom Ben Hayoun had been collaborating for years) and Ben Hayoun’s own funds.

“‘For a while I was making the joke that I felt like all of us had been kidnapped and we’re suffering—what’s that syndrome called? Stockholm syndrome.””

That private income, and the fact that some of it came from big tech companies, was apparently the reason the Sandberg Instituut ultimately withdrew from the partnership. Shortly before the course started in September 2017, a group of Sandberg students posted an article criticizing the university’s funding model and flashy profile: “The UUG appears to be ‘stunt-casting itself into significance,” they wrote. “Due to the frequent high profile promotion of the UUG through the name-dropping of its associates, the reputation of its sponsors, and the advertorials on It’s Nice That, etc, its association with the Sandberg has the potential to permanently alter the reputation of the Instituut and its students and graduates, many of whom are not comfortable with the affiliation.” Disconcerted, the Instituut’s governing body agreed to continue its affiliation to the end of the master’s program but not to take it further.

There were also internal issues. “Really quickly, it became negative,” says Ben Hayoun. Some UoU students began to feel that, far from the course being an opportunity for unshackled exploration, they themselves were being controlled and censored. They felt at times as if there was little room for dissent or collaboration and that the course was dominated by one very powerful personality. “I am known in the industry as a designer to develop a set of cruelties which is quite violent in [confronting] power structures,” says Ben Hayoun. “The power and the confrontation they got with their teachers, and myself included, [created] a reaction of reject[ion] for some of the students. In a way, it is part of the strategy.”

So was she experimenting on her students? Was the course itself some kind of staged experience? “Of course not!” says Ben Hayoun. “Once it started to get a bit heated with the Sandberg Instituut, one of the charges was, ‘Oh, it’s an experience!’ But it’s not.” So what did she mean by the “Theatre of cruelties?” “It’s a dramatic, immersive stage technique pioneered by Antonin Artaud and Bertolt Brecht,” she explains—and no, it didn’t mean cruelties to the students.

“It was very hierarchical,” says Evita Rigert, who came to the course from Switzerland with a background in fashion. “This course was not at all free, it was like, ‘You do it that way and you work that way.’” Some questioned whether all of Ben Hayoun’s connections with famous people really existed. According to the students, about half the advertised speakers appeared (including Jeremy Deller, Nadya Tolokonnikova from Pussy Riot, Savages, and Peaches), but the others—particularly those farther away from Europe—did not.

“It was chaotic,” says Heather Griffin, who had come to the course from Ireland with a background in graphic design. “Really chaotic…. You just make it up as you go along.” Some of the students did briefly talk of a coup against Ben Hayoun, but it never came to anything. “I asked many times if it is a giant experiment, because then it makes sense,” says Rigert. “I learned a lot [and] I always think things have a purpose in life, so I would not say now I would never [have done] it. But it was also torture.”

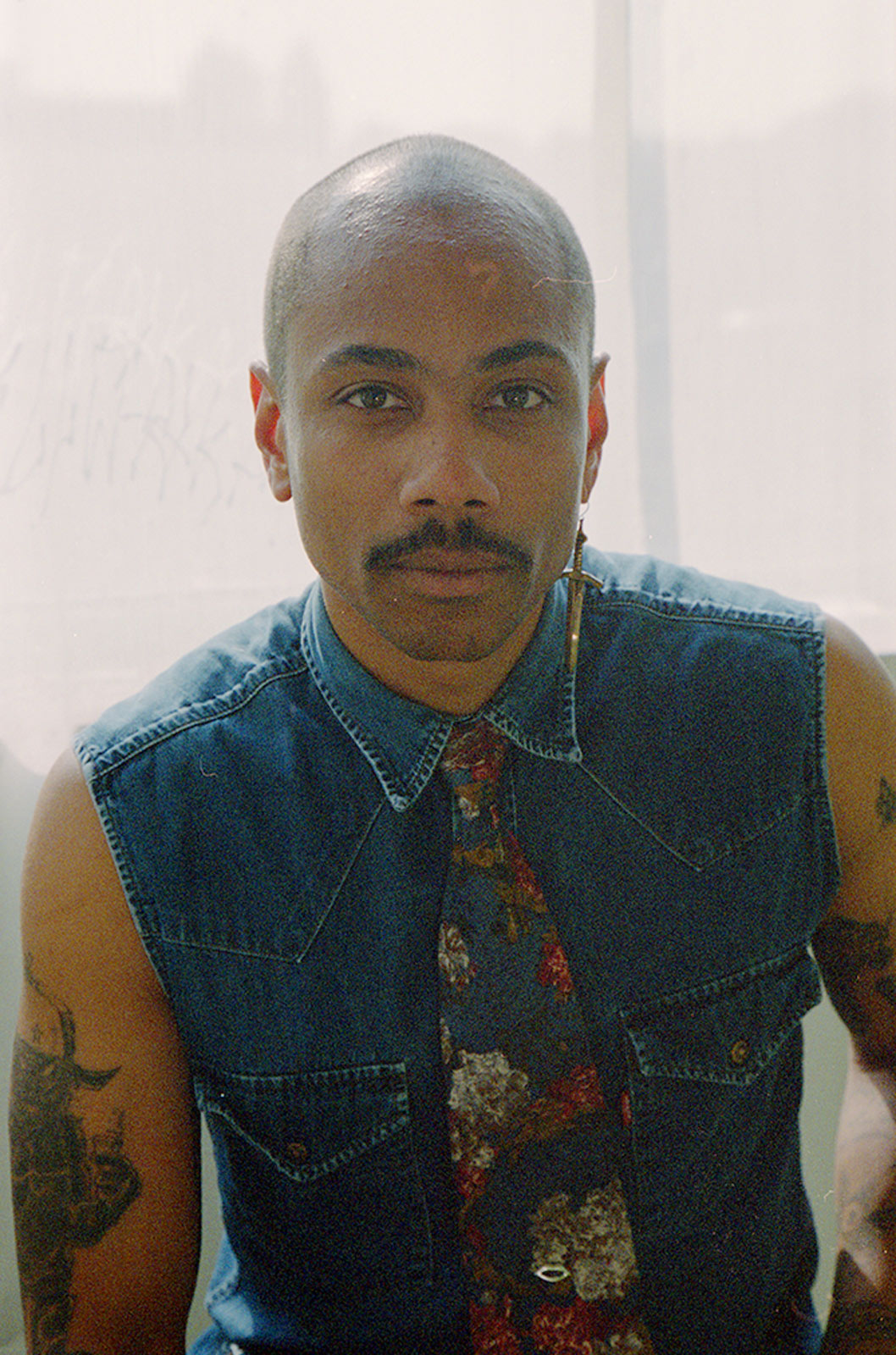

Alexander Cromer, who joined the course from a middle-school teaching background in Pittsburgh, calls it “Tumultuous, fascinating, heartbreaking. And love. Can I use love?” Yes, of course. “Actually, for a while I was making the joke that I felt like all of us had been kidnapped and we’re suffering—what’s that syndrome called?” Stockholm syndrome. Where you start identifying with your captor. He laughs. “Stockholm, yeah. It’s been weird.”

Ben Hayoun’s take on things is different. “It’s crazy to me what happened,” she says. “I was sitting in my studio, all happy, and suddenly it turned. Suddenly colleagues were questioning my work, bad-talking me.” Ben Hayoun denies that she’s in any way controlling, though at one stage she does talk of the students as “kids.” She concedes that she was unprepared for much of the pushback she got from both the Sandberg Instituut and the students, and that she found many of the criticisms painful. “I took them really personally, and in a way it was a really misogynistic way of coming at me…. I have my Ph.D., I have my credentials, and everyone was questioning the way I was using words, and I really didn’t appreciate that. I basically got censored. They didn’t like what we were doing [so] the students decided that we have to be removed.” Her response has been to make a film, I Am (Not) A Monster (planned for an October release), intended both to act as a kind of personal manifesto and to explain her bewilderment to a bewildered world.

At the degree show in the basement of the nightclub De Marktkantine in Amsterdam, the 14 remaining students have presented their work: poltergeists and social housing, subverting facial-recognition surveillance technology, fakery in counterfeits, ice, slavery and the Middle Passage, the lack of pluralism in censuses and autocorrect, a video game role-playing the experience of euthanasia. One student’s video alludes to difficulties within the program and her search for outside collaborators. There is music, friends, dogs, a viciously effective pastis liqueur, a smokers’ corner, a steady wander of people around the basement. Ben Hayoun is there.

The following day, at the graduation ceremony, she is really emotional. As for the students, all say the experience will take a while to process. And, though many feel that they did not get from the course what they expected to, they acknowledge the benefits of the past two years— not so much as a set of employable outcomes, but in skills with which to negotiate an increasingly politicized world, in wisdom, and—most of all—in experience.

McClellan says the UoU will continue. Ben Hayoun is keen to absorb many of the lessons from the first class, and to find a new partner with the intention of restarting the course next year. In August, she ran a four-week tuition-free program at Bard College in New York City, and she’s exploring possibilities in other parts of the world. As both Ben Hayoun and some of the students point out, it would be a shame to let the momentum of this first tumultuous class go to waste. For something of this scale and ambition to succeed takes time. “There was a lot of press for this program, and a lot of jealousy,” Ben Hayoun concedes. “But my most important work to date was this one.”

Dr. Nelly Ben Hayoun’s film ‘I Am (Not) a Monster’ will be released on October 10th at the London Film Festival. The University of the Underground will be accepting applications for a new class of research students in November 2019, and for postgraduate students in March 2020.