The fascinating story of two feuding magazines, and the ideological clash that catalyzed Germany's youth uprising.

The year was 1966. Mini skirts were all the rage and the Rolling Stones blasted from the radio. German women rushed in flocks toward magazine stands in furious pursuit of the latest issues of their style bibles. Beautiful models posed on alluring covers, bold in color and contrast. Despite speaking to the same demographic in the same language, the available copy on the shelf was determined by location. In the West, there was Twen—and in the East, there was Sibylle. They were separated by a wall built five years prior.

These beacons of youth culture chronicled the hopes, dreams, and fears of women born into one of the most politicized countries of the 20th century. They helped light the way for those born in the rubble of the Second World War, who felt a desperate need to distinguish themselves from horrors committed or suffered by the previous generation. Though faced with a similar burden, Twen and Sibylle illustrate the impact of the Cold War; the stark ideological divide that shaped their respective worlds in 1966 and beyond.

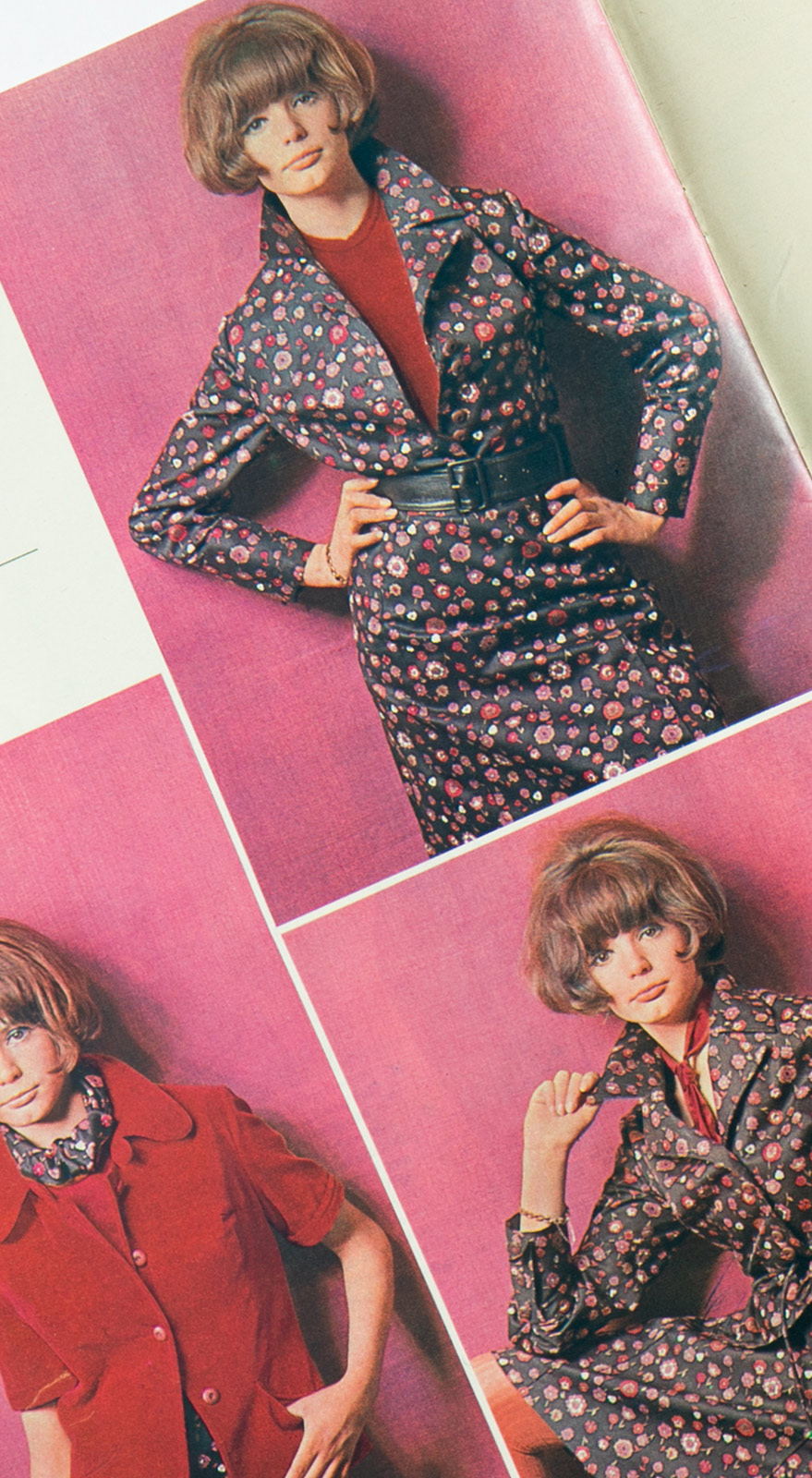

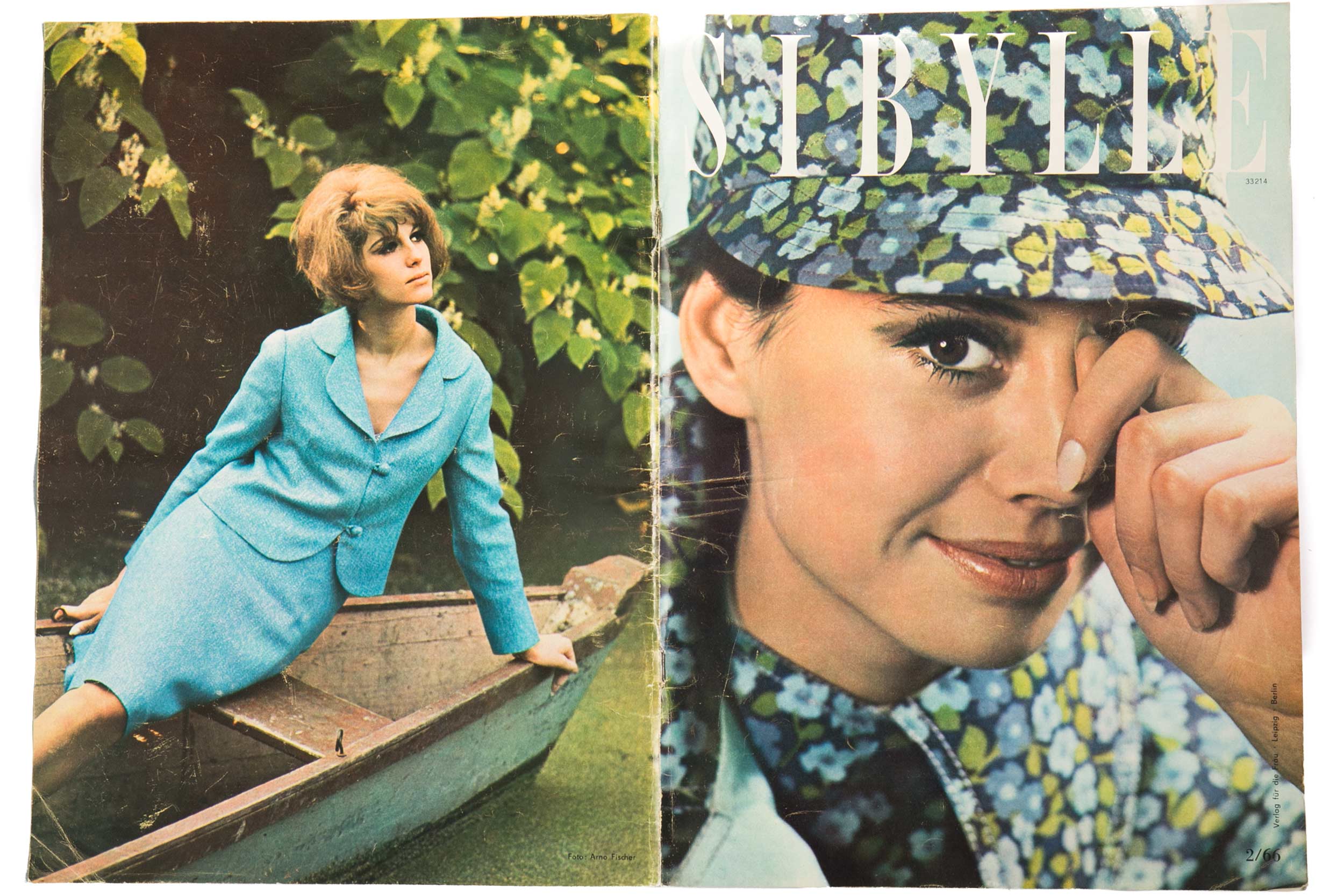

In this particular year, Western readers were greeted by a open mouthed brunette with the punchy headline, “COOKING POTS MAKE WOMEN DUMB,” while those in the East saw a woman in head-to-toe red, posing with the Kremlin, with the only text being Sibylle’s title. Both magazines sandwiched thoughtful essays and reviews between editorials with models sporting thick falsies, paisley, short hair, and working-girl suits. The surface-level stylistic similarities of the era are evident, but the significance of each publication differed dramatically. Twen was a provocative look in the mirror and Sibylle was a cherished escape.

Those traversing between magazine stands in the West and those in the East would have seen neon lights advertising products and places (bustling cafes, clubs, restaurants) fade into the grey superblocks of the German Democratic Republic. There, bureaucratic and tenement buildings served as their own kind of advertisements, not for a product, but for the Communist Party. The respective idols of each German society shaped Twen and Sibylle; depending on which side of the wall you called home, the Western woman was enslaved to—or liberated by—consumerism, and the Eastern woman was enslaved to—or liberated by—Socialism. Cold War mentality necessarily propagated contrasting views of the modern, aspirational woman.

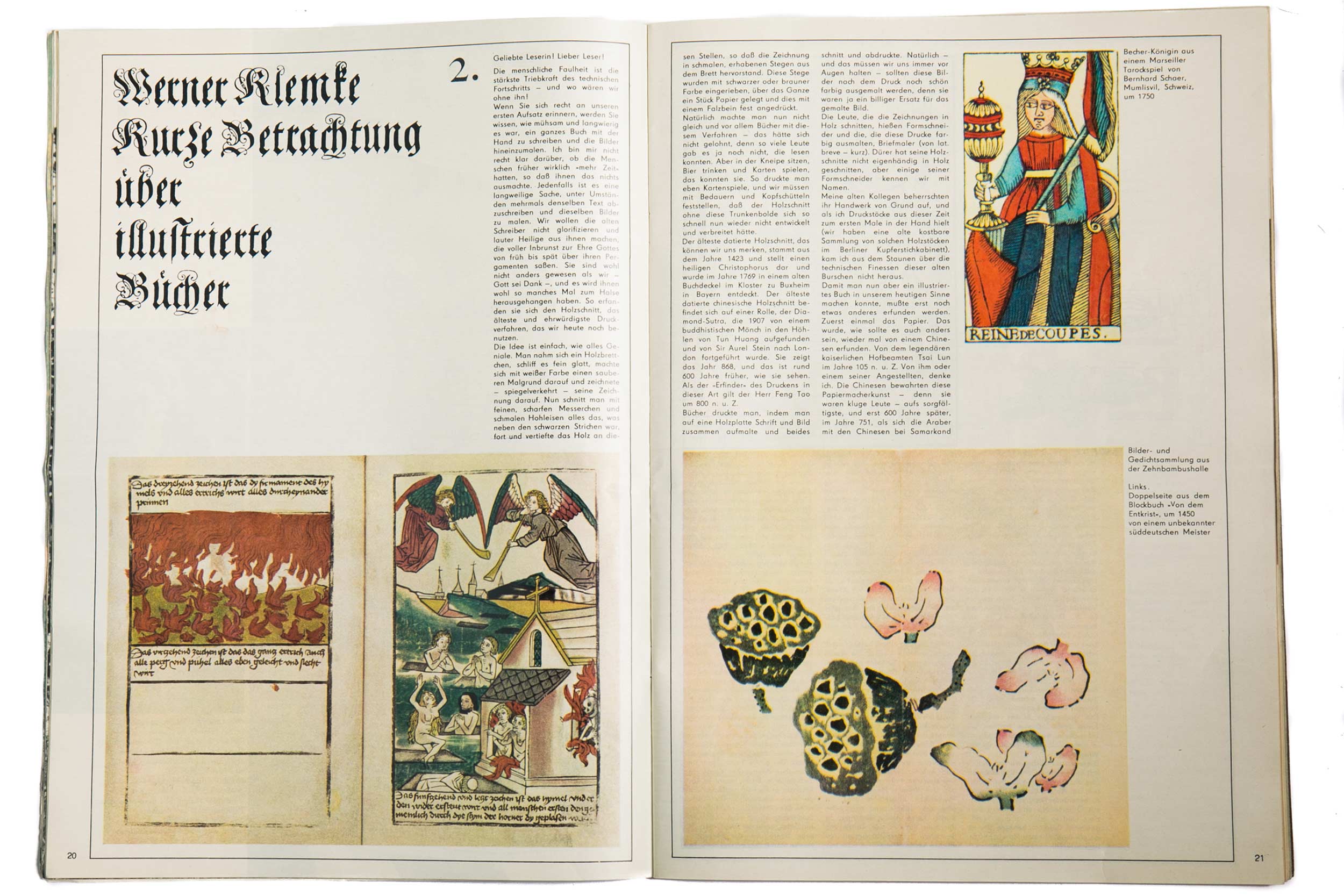

The notoriously eye-catching Twen had a name derived from the word for its target readership: girls in their twenties. The publication launched 60 years ago, in 1959, and had a short but powerful 12-year print run. Twen was the masterpiece of Willy Fleckhaus, who has been called the most influential magazine designer in post-war Germany, as well as the world’s first art director, given that he invented the job position. Taking inspiration from Swiss formalism, Fleckhaus designed the publication around 12 columns and an endless series of coordinates, which he rearranged to create inventive layouts. His taste for images with drastic crops, unusual proportions, and the unforeseen addition of rounded corners shaped Twen’s signature graphic identity; leaving a mammoth design legacy that sparks imitation to this day.

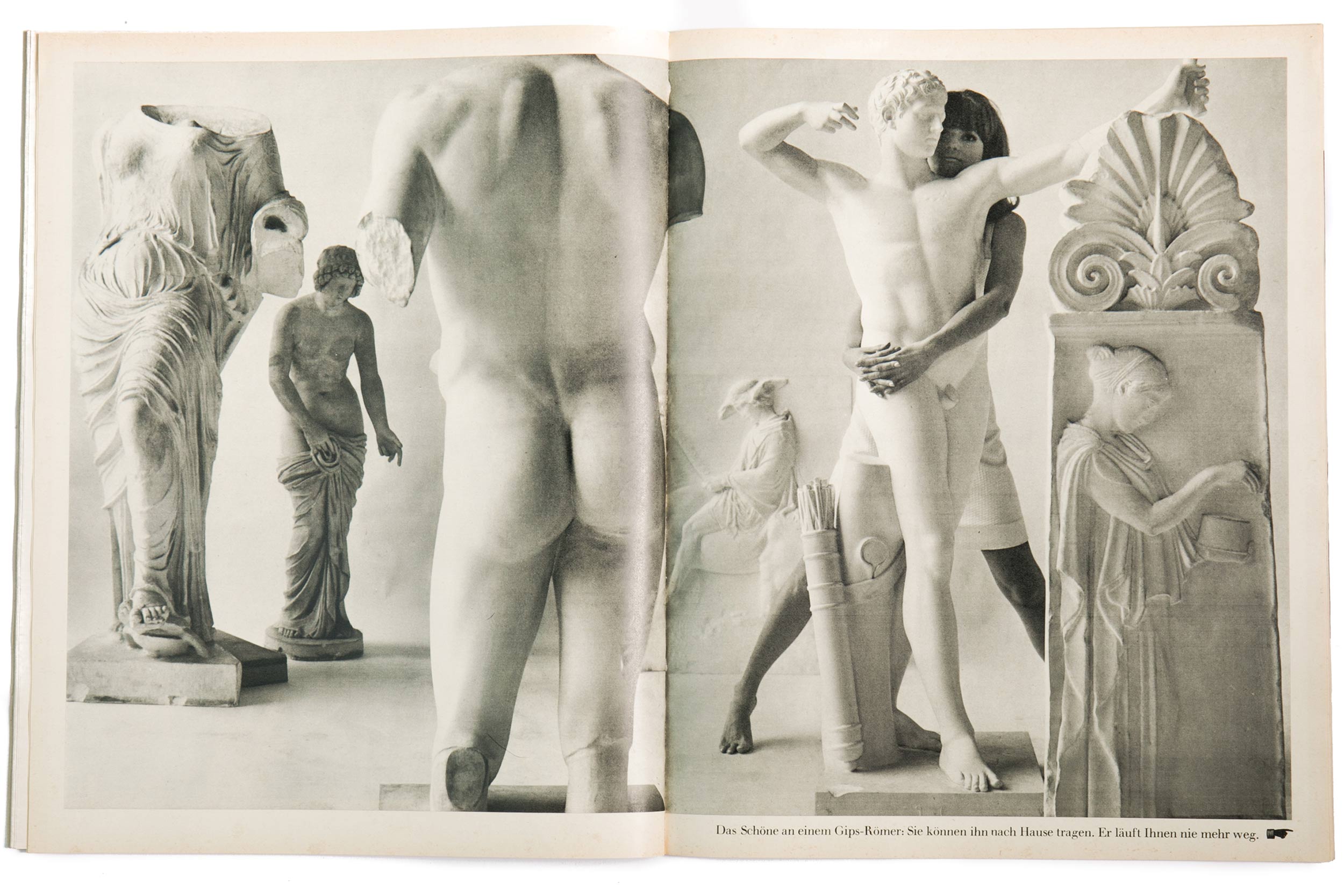

The magazine made heavy use of solid black; another hallmark was sans-serif headlines—‘1966: THE YEAR OF SEX’—that had every intention of raising eyebrows. They were fitting appetizers for the contents inside: texts and op-eds that often dealt with taboo or ‘amoral’ topics, like premarital sex, homosexuality, and compulsory military service. To the delight of the Twen team, the magazine was no stranger to controversy. In 1961, critics took Fleckhaus to Munich’s high court, charging Twen with being more dangerous than pornography and breeding super individualism to society’s detriment. The publication that was a slap in the face of the older generation functioned as a playful spank for raucous and experimental youth. The Tweneration’s desire to restructure social values and morals felt paramount in West Germany, when previous members of the National Socialist Party still held positions of power.

Today, Twen is recognized as an important catalyst for West Germany’s Sexual Revolution and its 1968 Student Movement (68er Bewegung), an organized reaction against the perceived authoritarianism and hypocrisy of the West German government. Twen responded to the copies of The Feminine Mystique being passed around campuses and was an early adopter of a Second Wave Feminist mindset. The Twen woman was socially critical, politically active, and sexually liberated.

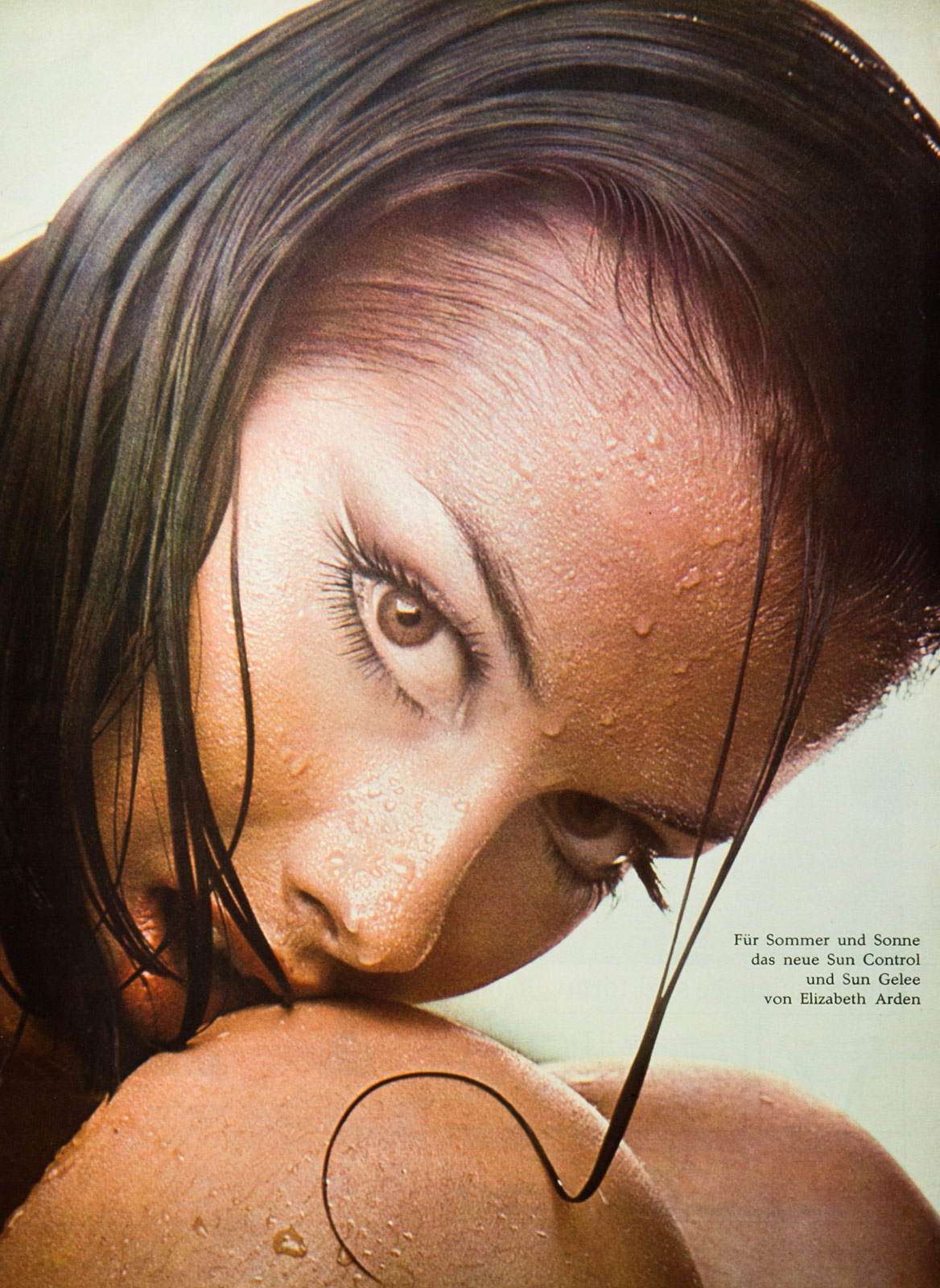

While Twen was a beacon of radical ideas, it was also a beacon of products. Radical ideas are sandwiched between ads for alcohol, cigarettes, and perfume; a reminder that in Western capitalism, consumption characterizes everything—even rebellion. The Tweneration rebels, proponents of hedonism and daring style, were taught to mirror intellectual resistance with their purchasing power: buy to identify.

Across the wall, Sibylle readers had no such freedom. With spies and informants infiltrating virtually every aspect of public and private life, expressing discontent was dangerous. Subtlety was Sibylle’s only recourse. The mag’s 1966 April cover boasted an intimate close up of a woman in blue floral, winking at the reader, as if sharing a secret with them. Though out in the public and sanctioned by the state, Sibylle gently went against the grain. The magazine’s rebellion lay in its reverence for style; a taboo idea in a society of brutalist buildings and social realist paintings that dismissed a reverence for beauty as bourgeois. Physical attractiveness was seen as an interest of oppressors.

Sibylle, the ‘Vogue of the East,’ stands today as one of the GDR’s greatest artifacts and anomalies. Though the very concept of a fashion magazine may seem to epitomize Western aesthetics and consumerist values, the East German team of creatives behind Sibylle manifested the impossible. The publication was founded in 1956 by a German-Jewish esthete, Sibylle Boden-Gerstner; a devout Socialist who dared to suggest that beuaty, glamour, and fashion weren’t at odds with the aims of an anti-fascist state.

The magazine that bore Boden-Gerstner’s name strove to deviate from the typical woman’s magazine limited to gendered topics like cooking, housekeeping, and family care. She strove to include the highest quality academic writing and artistic images to supply East German women with enduring sustenance, keeping readers within the cultural landscape of the Soviet Bloc. But after just four years at Sibylle, Boden-Gerstner was forced to step down from her own magazine due to external threats; her aesthetic vision was criticized for being too cosmopolitan, too international, and ‘too French for Socialism.’

After her departure, the ‘60s at Sibylle reflect the push and pull between censors and creatives testing the boundaries of the messages they conveyed through text and image. It granted photographers like Arno Fischer, Ute Mahler, Roger Melis, Günter Rössler, and Sibylle Bergemann a sacred exhibition space and greater artistic liberties than traditional photojournalism could. Images made under the fashion umbrella were given more leeway, as they were alleviated of the responsibility to reflect reality and the government’s version of it. But the Communist Party underestimated the potential for political subversion in the ‘mere’ fashion mag. By focusing scrutiny elsewhere, the state allowed for an unprecedented convergence of artistic and documentary styles, and the production of some of the most impressive works in the canon of East German photography.

As economic hardships in the GDR became more severe towards the end of the decade, the propagandistic aspect of Sibylle became inflated. Women were shown in workwear and overalls, riding the U-Bahn or walking about town. Fashion photography emphasized the elegance of the everyday. Well aware that the clothes exhibited could not be purchased behind the Iron Curtain, each issue contained sewing patterns, so that women could attempt to make the garments shown at home. The Sibylle woman had to be, above all else, a working woman. Those not in hardhats were shown as diligent students, or in the Kremlin ‘66 issue, as disciplined Soviet ballerinas, making visible contributions to socialist society. If Twen sought to reach liberated women, Sibylle sought to sustain a readership of intellectual and capable ones.

Striving to remain relevant and edgy proved challenging for Sibylle given the huge confines of censorship and the scarcity of resources. Even so, it triumphed, and became one of the most cherished pieces of youth culture in the GDR. Sibylle was a colourful escape from socialist realities; it awarded its loyal readers access to an alternate, stylish world—one that provided alleviation from a daily life dictated by postwar uncertainty.

Unlike Fleckhaus and his magazine, which died young, Sibylle died a slow death. Twen’s firecracker run preserved it as a poignant portrait of a historical moment and cemented its place as the definitive publication of Germans in their twenties at that time. Sibylle, as the GDR’s only fashion magazine, was able to retain its influence up until Reunification. Suddenly forced to compete with established, powerful, and wealthy Western publications, Sibylle folded after 1989, along with the GDR.

Today, the magazines show a split generation, bonded by age, language, and historical trauma, but separated by location and ideology. Though these women were shaped by dramatically different sets of limitations, there’s an undeniable zeitgeist that linked them, blending East and West into the singular category of German Youth. Twen and Sibylle reflect a precious blend of discontent and optimism, the precise qualities that helped break down the wall between them and end the Cold War.