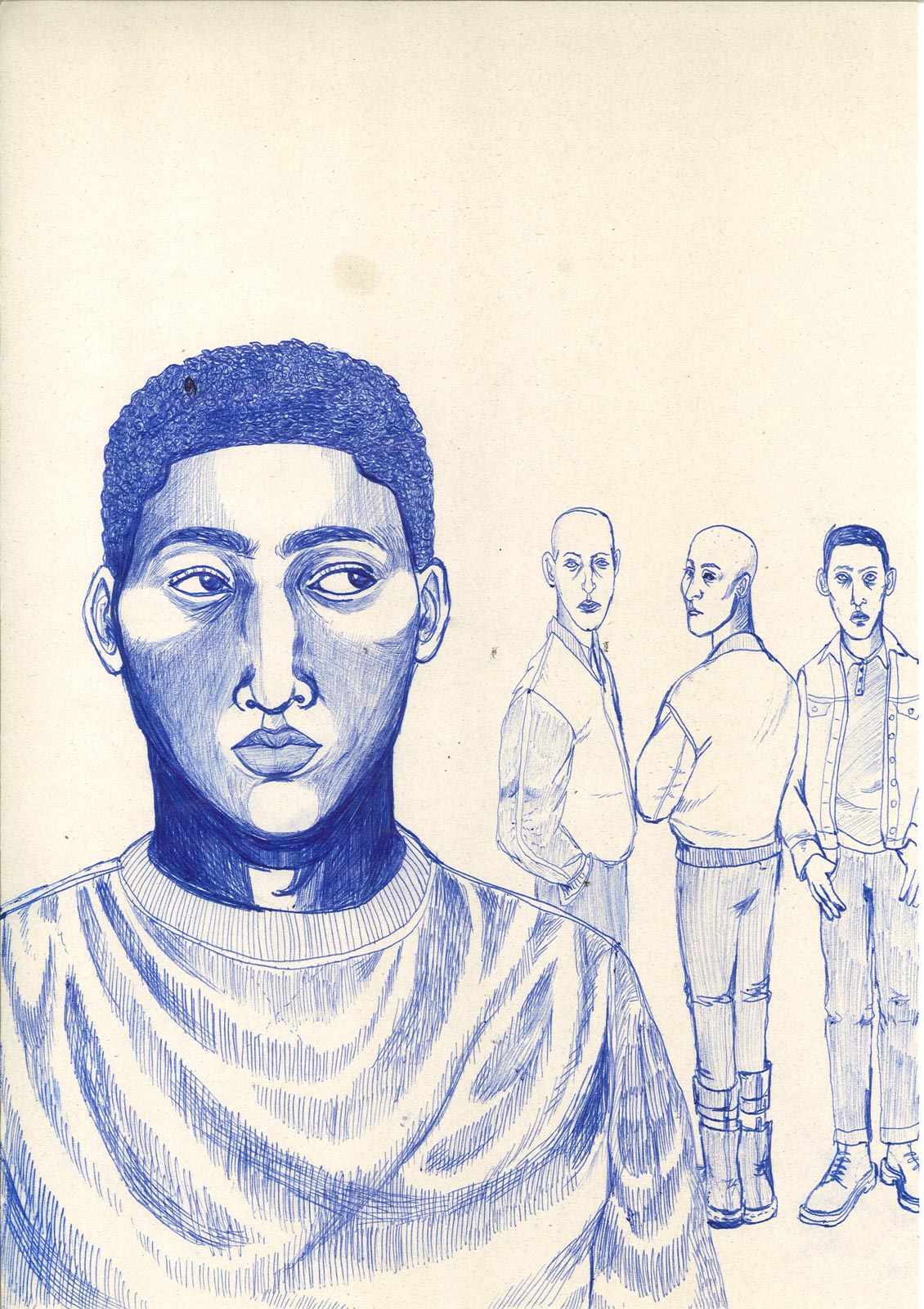

The artist's multimedia anthology exposes the disparities that still exist in the mental health conversation, particularly in regards to men of color.

With each passing day we are bombarded with a wealth of new wellness-centered products, classes, podcasts, books, regimens, inspirational posts, and the list goes on. While our newfound interest in mental health certainly holds promise, many of our approaches remain grounded in consumption. Products cannot address our many specific needs and experiences; they are unable to make space for individuality and personal expression.

Writer and model Hélène Selam Kleih’s HIM + HIS provides a communal approach to mental health. A stunning anthology of multimedia specifically focusing on men’s mental health, HIM + HIS was born out of Hélène witnessing the sectioning, or institutionalization, of her twin brother. As her family began to navigate state run mental healthcare facilities and treatment, Hélène noted the many ways her brother’s needs were not being met as a young man of color. She began to reach out to others around her, friends and coworkers and beyond, creating a large network of individuals who are interested in pursuing alternative narratives as well as means of caring for one’s mental health.

Document spoke with Hélène about the formation of HIM + HIS, the disparities in mental health care, and the importance of centering creative expression as a means of coping. The care that Hélène approaches this project with serves as a reminder of the wonders that can spring forth when steadfastly committed to community, even in the midst of our most challenging experiences.

Allie Monck—What motivated you to begin this project and approach men’s mental health from this angle?

Hélène Selam Kleih—I was interested in why the state of mental health within men was so bad. On the table of contents page I wrote, ‘There is no order, there is no filter.’ I can’t classify what my brother has gone through or what he is going through right now. Neither can I classify what us as a family has gone through, or his friends, or from the outside and how they view him. When we come up with these classifications on people it stigmatizes what people are going through instead of thinking of the person and the human. They’re now either a percentage once they’ve been put into the system or they’re a statistic or they’re a tragedy, and all of these dehumanizes the person. That’s what the point of HIM + HIS is. Him is the notion of the physical being and His is having possession over oneself.

Allie—Did you initially plan on the book including a vast array of writing and media or was it an organic process?

Hélène—It was literally a rolling basis of me initially talking to friends. It came organically through discussions. It was just, ‘Hey, this is what’s happening to my brother; I want to create something that could speak to him and speak to others. Whatever creative medium you use.’ I wasn’t asking photographers to send in photography work. They could literally send me five lines of whatever they wanted to put in.

Allie—Did you find the editing process took a toll on you? How did you manage to prevent it from being too overwhelming and ensure your own mental health was being attended to?

Hélène—A lot of people didn’t even know that I had a twin brother, and at the time, it was very traumatic. I’d be going to an institution pretty much every day straight from shoots. I think a lot of people were shocked that I had never relayed any of that information. One, because of the stigma but also because it was this kind of preservation. ‘If I don’t tell anyone it’s not happening,’ kind of thing. I was also lying to myself because that’s not how a community grows or how a community can help you. If you’re not speaking there’s no notion of ever receiving support. It was quite a lonely journey even whilst creating the book. It was quite stressful, but then I think once it came out, there was an enormous amount of support. It completely surprises me with how many people came forward to help and they’ve never even met me.

Allie—What was the editing process like for you?

Hélène—The first piece we had from Akinola Davies. He is a director in London who used to be known by the name Crack Stevens, and he also DJs on the scene. His submission was a letter to Benga, when Benga came out about his own mental health. Honestly, it made me cry because it was someone I not only respected but someone who I got on with more in a working capacity, who I had never expected had gone through those things. When he sent me that, I was like, ‘this is brilliant.’ It also gave me the validation that I could continue.

Allie—You speak a lot about prevention, and it’s interesting to hear about the way that institutionalizations work in the U.K. versus the U.S. In addition, you have spoken about the ways medication can serve as sedation, what do those differences mean to you?

Hélène—You’re prescribed just based on what you have; your diagnosis becomes you. When you have a lack of agency it’s because you’re not a person anymore, you’re your medicine. For example, my brother’s dosages, whether they increased them or decreased them really impacted how he felt as a person. That determines how he reacted to us and how he was going ahead and getting better. With medication, it’s how we can attach prevention, how we can look at working communities, and making communities, growing them ourselves, work forward within them to prevent tragedies.

Allie—With dramatic levels of gun violence and white supremacist violence, a lot of times our response in the U.S. is, ‘Oh, they’re mentally ill. They’re troubled or shy.’ I don’t know if similar things happen in the U.K., but there are odd ways that mental health has become politicized. Can you speak to that and how you respond to those challenges in your work?

Hélène—I think the largest issue that has to do with mental health is race. What a Black man feels when he is profiled consistently and his identity is mis-received. My brother would continuously be profiled because he’s mixed race, but also his reaction to the police would be a detriment to him. He doesn’t maintain eye contact; from that alone they wouldn’t think, ‘Okay, mental health issue.’ They would focus on his race first. Those things can impact someone’s mental health, and afterwards they’re deemed ‘crazy’ and when a Black man is crazy that’s different from when a white man is crazy. It’s a lot easier to then focus on the white man’s mental health. When Black men are sectioned, the way they’re treated is different. It’s easier to go down the sedation route because they are valued as less human. Sedation is just keeping you quiet. You’re a vegetable.

Allie—The color green seems to have emerged as a theme in both the book and events you’ve hosted. You posted ‘Green is for Prosperitee’ and I wanted to ask if you can share what that means.

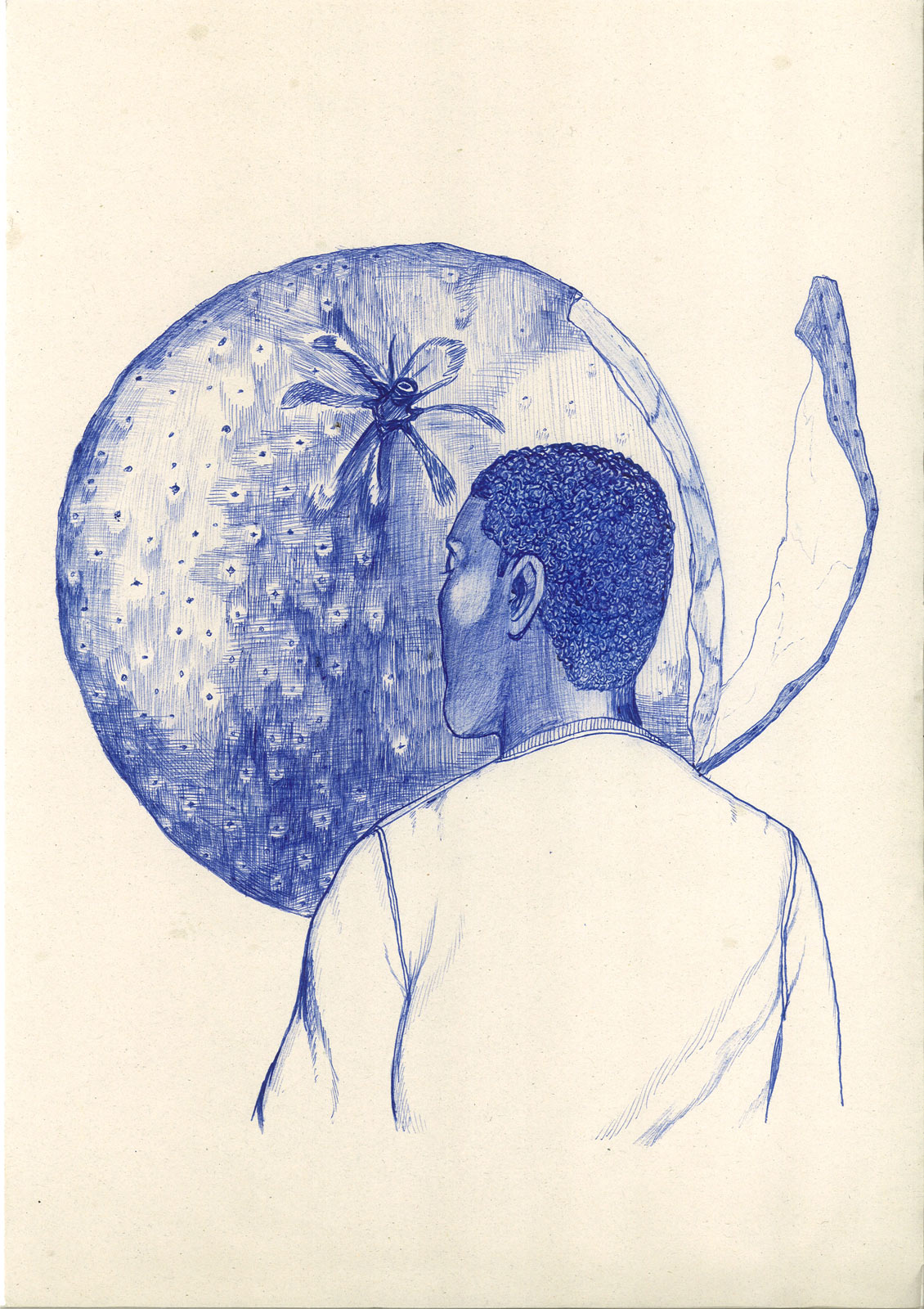

Hélène—I just chose [green] because it’s a universal color that is quite neutral; it doesn’t really have any kind of association with a gender. When my cousin passed away in 2017, for him to have committed suicide when he was the one pushing me along, there was a notion of, ‘I don’t know how to go forward if he’s done that.’ I found out the day I was going to Lagos; I was with one of my best friends and one of the first signs we saw after getting off the plane was for ‘Prosperitee Furnishings.’ From that, I kind of coined, ‘More Prosperitee.’The green represents vitality and health in a way that I hope represents a new version of health. Health doesn’t have to be medical like blue. Green also represents treachery and grief, that duality of someone’s identity can also be healthy. I say ‘treat the root before the rot.’

For submissions for the second edition of HIM + HIS, you can email himandhis.info@gmail.com and stay updated on events @himxhis.

In the coming year, Hélène will be releasing a feature documentary based on HIM + HIS. Set within Hélène’s personal story and those of the contributors, the documentary looks at the larger conversations around male mental health, toxic masculinity and its effects on family, friends, and society. How can creativity be a form of prevention? How can we treat the root before the rot?