The exhibition, curated by Natacha Polaert, features pieces from Dan Colen, Ouattara Watts, and Walter Robinson, among others.

Glenn O’Brien was a mythical figure in downtown New York who embodied the worlds of art, fashion, film, and music that emerged from its streets during the ’70s and ’80s. He entered the downtown stratosphere as a member of Andy Warhol’s Factory and was later appointed by the artist as Interview’s first editor. He supposedly coined the term editor-at-large while at High Times because it was best for him to be away from the office, out in the trenches, avoiding the authorities. O’Brien wrote the screenplay for New York Beat; a film that starred his best friend Jean-Michel Basquiat, was directed by Edo Bertoglio, and was post-produced decades later by O’Brien and Maripol, before it was finally released in 2000 as Downtown 81. His candor would make its way onto public access television in 1978 in the form of the show TV Party, which featured guest appearances the likes of his friends Basquiat and Fab 5 Freddy. After he stepped down as host in 1982, O’Brien edited Sex, Madonna’s controversial coffee table book. In his final decades, O’Brien was perhaps best known as GQ’s Style Guy, for the monthly column he penned for the men’s bible. He was a man about town, an arbiter of style, a maker of taste, as well as husband to Gina Nanni and father to Oscar O’Brien.

O’Brien, who was also a contributor to Document, was a hero to many, including fashion, art, and design consultant Natacha Polaert. “He was someone that I admired from afar and at some point, I had the right project to reach out to him,” recalls Polaert. The 2012 project was for St. James, the iconic French shirtmaker known for its nautical striped shirts. Polaert refused to ask her acquaintances for O’Brien’s contact information, instead guessing several combinations that could be his email address. “Most of the first name last name combos bounced, and only one stuck—it was the mac.com,” remembered Polaert. O’Brien responded immediately with the words, “These are my favorite shirts in the world. I’d be really into it. And if you can believe ancestry.com, I’m descended from William the Conqueror.” The writer and his son Oscar ended up appearing in the pages of a St. James calendar.

O’Brien would pass away five years later, in 2017, at age 70 due to complications from pneumonia. Polaert wanted to remember O’Brien through an art exhibition inspired by him, so she asked Nanni, his widow, for her blessing. Nanni agreed, knowing very well that her husband would have been on board with the idea. The result is Glenn O’Brien: Center Stage, on view at Off Paradise on 120 Walker Street in New York until November 27.

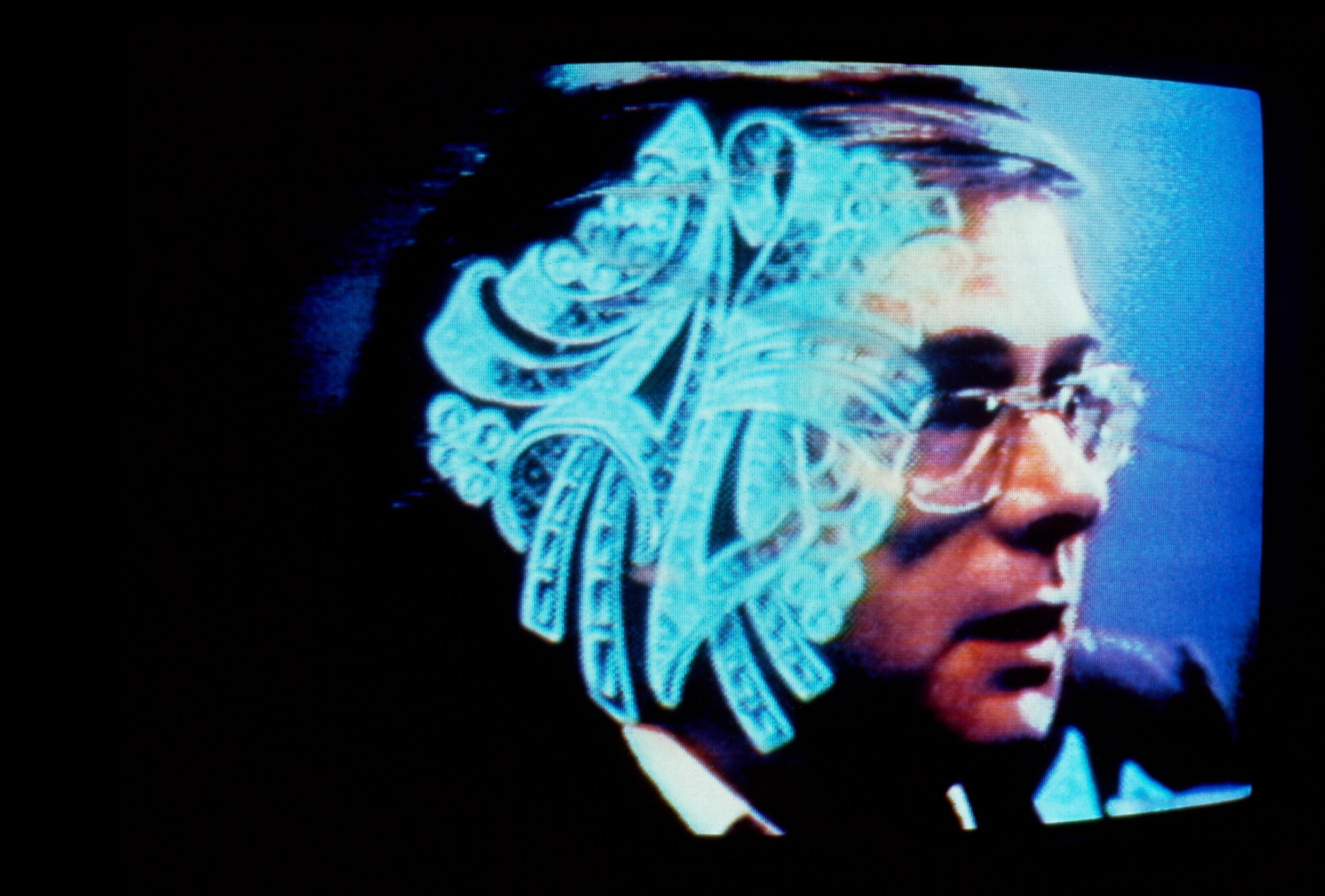

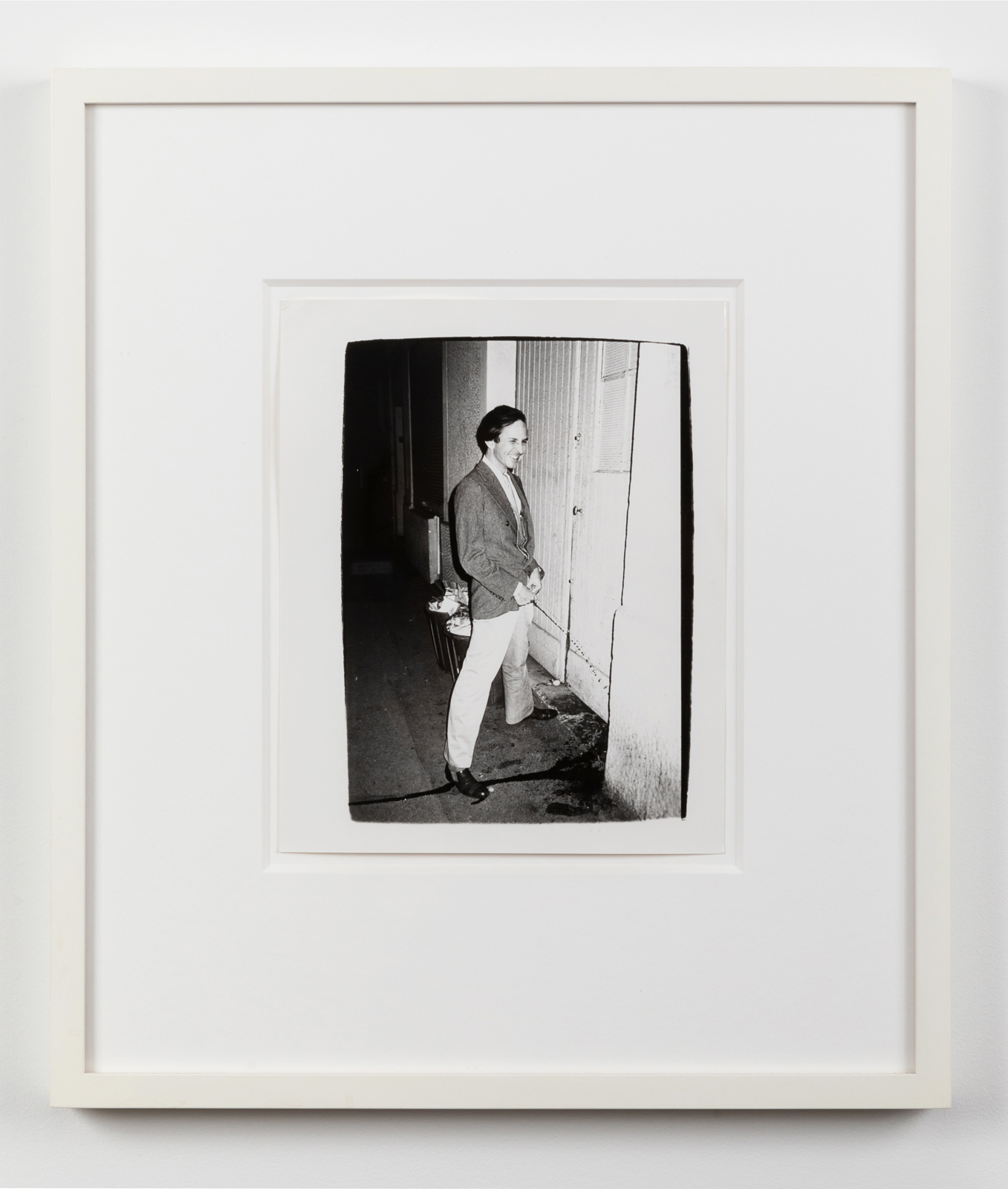

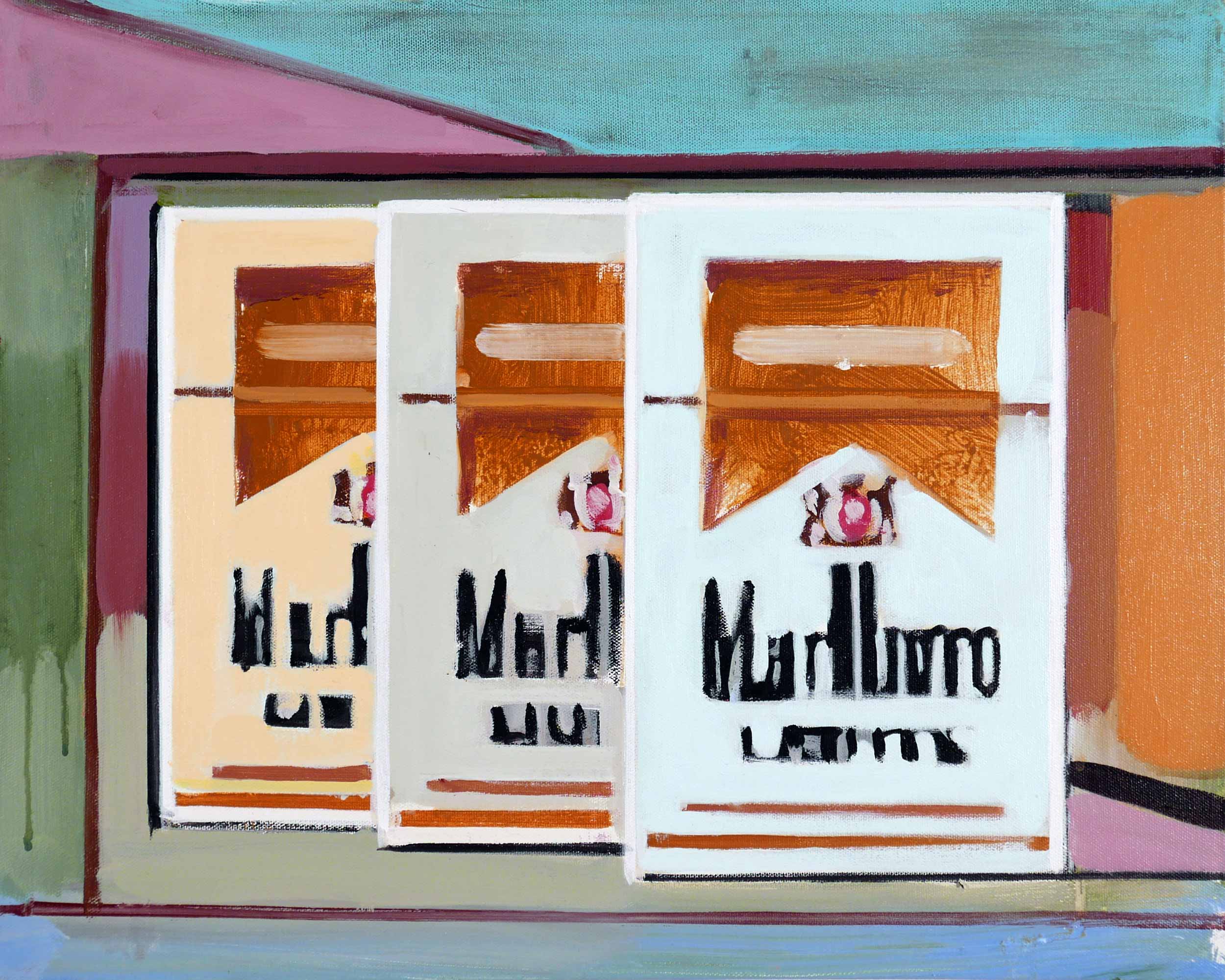

Polaert put together a group of artists who circulated in O’Brien’s orbit from the ’70s until now. There’s a cheeky 1978 photograph by Warhol of O’Brien’s Interview mentor Fred Hughes peeing. O’Brien’s time as an ad man—he worked on the infamous Calvin Klein campaign shot by Stephen Meisel—is represented by a 1976 ad campaign conceived of by Dennis Oppenheim that ran in Art in America and other publications to promote his 1976 solo exhibition at ML D’Arc Gallery. To represent O’Brien’s first art purchase—a set of disposable sculptures by Les Levine—there’s the 1977 video “Diamond Mind” by Levine, filmed in a control room at Syracuse University. From the ’80s, there’s the aptly titled 1989 work “TV Party” by Martin Wong that Wong made years after O’Brien’s show ended. From the aughts, there are a set of skateboard wheels by Tom Sachs, as well as contributions from two younger artists O’Brien respected—M&M sculptures by Dan Colen, and piles of fabric and a black studded glove encased in a glass vitrine by Dash Snow. The newest works are by contemporaries of O’Brien; a painting by Ouattara Watts, and a painting of packs Marlboro Lights—O’Brien’s preferred cigarette even though he had quit smoking—by Walter Robinson.

The work that is perhaps the most poignant is Claude Rutault’s 2019 homage to O’Brien, “Bookshelves: A Portrait from Afar.” The piece features a life-sized version of the bookcase in O’Brien’s Bond Street loft. Although Rutault, who says he “writes” paintings, didn’t know O’Brien personally, they lived in New York at the same time. On the shelf we see monographs of artists like Ed Ruscha, Robert Mapplethorpe, Keith Haring, as well as a number of copies of Wyndham Lewis’s The Apes of God, evincing O’Brien’s predilection for collecting first-edition books.

Polaert remembered something that writer Carlo McCormick told her after seeing the books, and the several obscure titles that lined the shelves in O’Brien’s home: “‘We are still learning from Glenn.’” Indeed we are.