5 stories of heartbreak, cruelty, and vibrant, resilient spirit—told by Cruz and his colorful, floral portraits.

David Antonio Cruz wants to give queer people of color a place in art history. Through his painting, sculpture, and performance, Cruz gives his subjects a sense of dignity, visibility, and beauty despite the tragic narratives in their lives. Embedded within Cruz’s paintings are layers of code; the foliage often represents plantlife from the same place as the subject; certain colors also mean different things—green, for instance, signals immigration. Cruz’s practice explores the intersection of homosexuality and race, highlighting the complex stories behind the faces in his work. A series of these portraits are featured through October 26 in One Day I’ll Turn the Corner and I’ll Be Ready For It at Monique Meloche in Chicago.

Although Cruz doesn’t know many of his subjects, their narratives align with his own in many ways. He was born in Philadelphia to Puerto Rican parents, and identifies as Latinx, black, and queer. Cruz spent his youth protecting himself with an “invisible shield,” not to draw attention to himself in order to avoid being bullied or harassed. “[I spent] so much of my earlier years trying to navigate that space silently,” remembers Cruz, who found solace in art. “It was the safest thing for me, it was just a way for me to create a place for myself.” Cruz found himself coming out to his mother in a conversation the summer following his freshman year after his sister broke the news to her. “It did not go well,” he remembered. “It was something that—as much as she loved me, as much as I was the baby—was really challenging in our family.” The artist would immortalize his mother, who passed away two years ago, in a painting that emulates Michelangelo’s Pietà, with Cruz as Jesus and his mother as the Virgin Mary.

“So much of my work now is a reaction to that,” said Cruz of his younger years. Now, his portraits portray those who fell victim to violence targeted at homosexuals. Cruz would piece together their lives, collecting images and videos from social media, posting them on his studio wall. “I wanted to become part of my consciousness, I want them to filter into my life in every possible way,” he said. Most of Cruz’s subjects are strangers to him, one exception being Dee, an artist who Cruz met in his youth in Philadelphia as Wesley before he transitioned to Dee. Dee tragically died a few years ago, and Cruz painted a portrait of her that hung on the Brooklyn Museum. “[I remember] talking to her through the moments when she was transitioning, the challenges, and it hit hard,” he said. “Painting her was going through 20 years of memory.”

Their names are Shantee, Dejanay, Camila, Janelle. They could have been our classmates, our neighbors, our friends, and even our family. Cruz shrouds their memory in lush, exquisite backgrounds, painting them as stars, divas, and models—giving them the allure, beauty, glamour, and pride that they should have celebrated in life. In doing so, Cruz preserves their legacy in a way that is traditionally reserved for the wealthy. Below, Cruz describes his process and intent behind five of the paintings in the Monique Meloche exhibition. “I want that that maybe that if in this lifetime we’re not looked at, that painting or art has that power, that maybe 10 year, 25 years, 50 years, and if this planet is around maybe 100 years, maybe what if someone goes back and wonders, Who is Ava?”

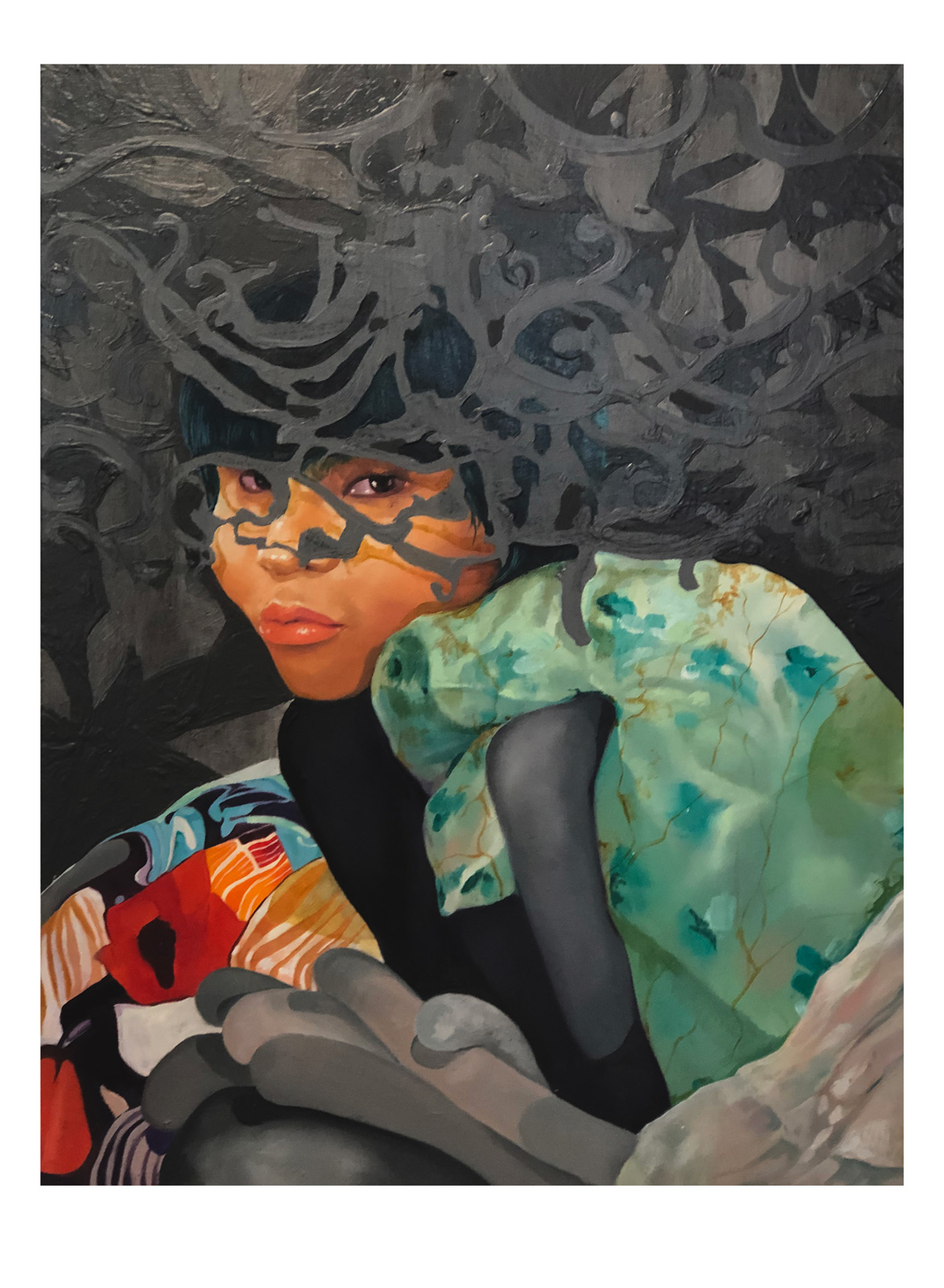

hauntmeinmydreams,ifyouplease, portrait of Shantee, 2019.

Shantee Tucker was a 30-year-old transgender woman from Philadelphia who was murdered in a shooting last year.

“I didn’t know Shantee, the case is completely unsolved,” said Cruz. “I constantly go back to look at the cases. It’s not only looking, but it’s also how the cases are being dealt with, or looked at, or examined, or the law. She was shot, people know how it happened. But no one’s ever come forward to identify the person that did it. And so there’s the silence around it.”

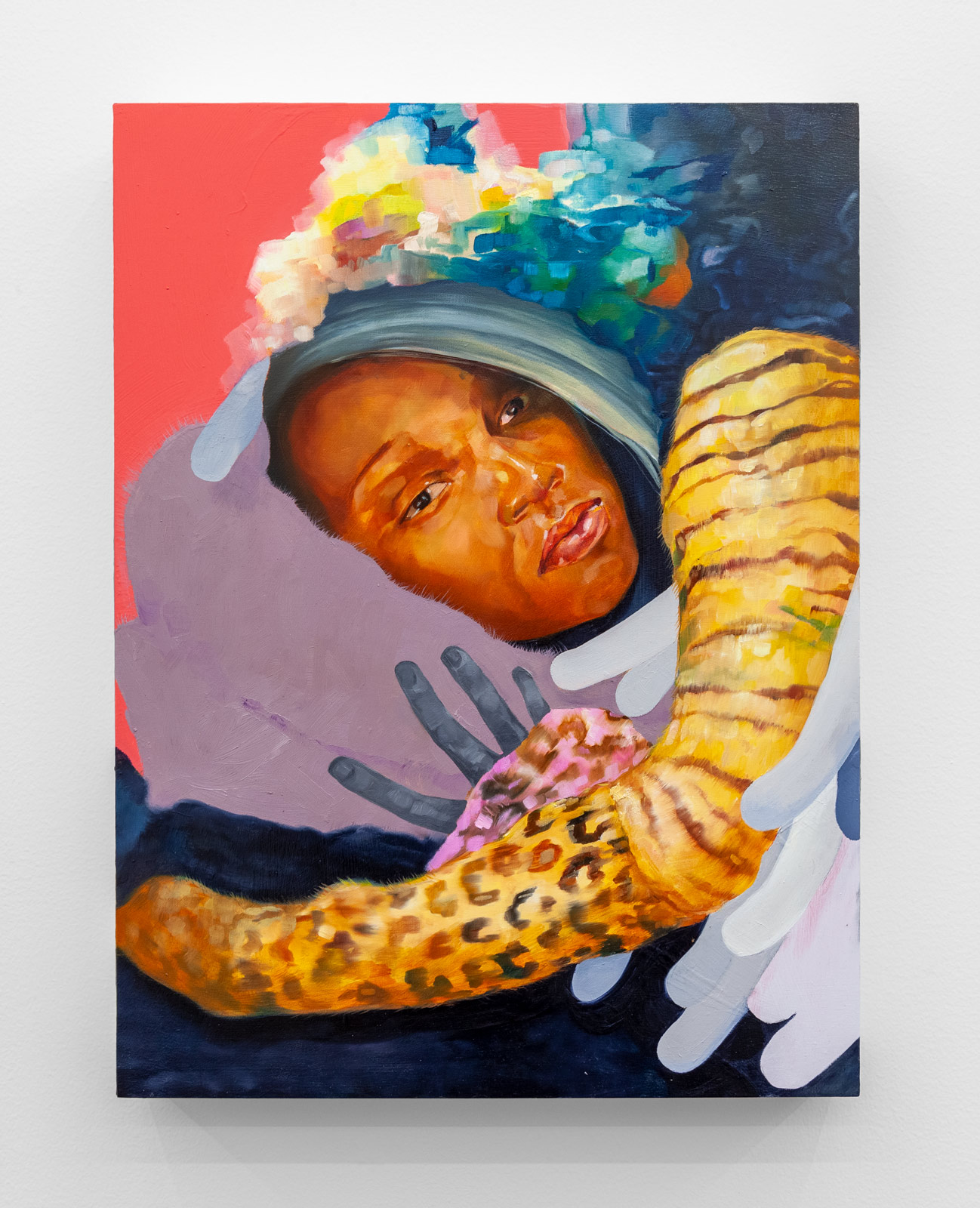

De’ Janay Stanton was a 24-year-old transgender woman was murdered in a shooting in Bronzeville, Chicago in 2019. Cruz posed her based on a photograph of Grace Jones.

“I wanted to think about Chicago,” said Cruz. “She is posed after an early image of Grace Jones. It’s almost like she’s sleeping, lost in thought, like if you would catch her in her bedroom thinking. The person has been charged with the crime, and they’re being prosecuted for her murder. She knew the person.”

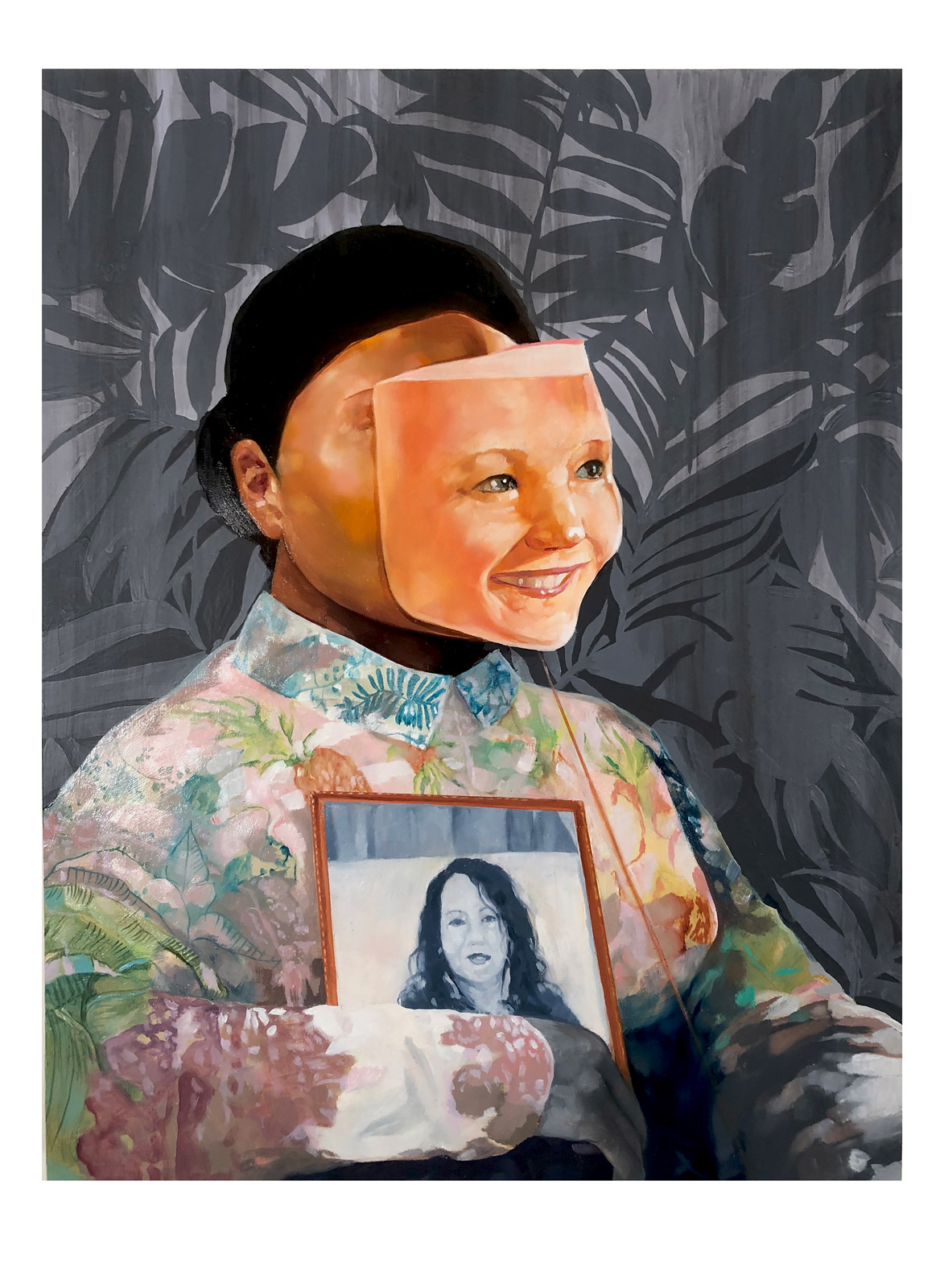

suddenly,youandiwillwaitinyourdreams…tonight, portrait of Camila, 2019.

At 31, transgender woman Camila Díaz Córdova attempted to move to the United States in hopes of gaining refugee status. Her request was denied, and she was murdered in El Salvador shortly after returning from the United States.

“She was part of that caravan thing that the country was politicizing, and she came in from El Salvador, where she was abused, battered, and attacked,” said Cruz. “She came in and was asking for asylum and was [denied and] sent back. She was murdered [after] she was sent back to El Salvador. She came [to the US], and she was being held, and then she was deported. So much of it is the idea of class, gender, and race, and I wanted to have a mask, you put on this mask—what happens, does it lead to safety, does this become a cover up in a way that you save a life, because your brown skin or your black skin is the target?”

onedayi’llturnthecornerandi’llbereadyforit, portrait of the Texas girls, 2019.

In this painting, Cruz depicts four victims of hate crimes: Brandi Seals, 26, who was killed in a shooting in Houston in 2017 (bottom left); Janelle Ortiz, 28, who was murdered by a serial killer in Laredo, Texas, in 2018 (top left); Kenne McFadden, 27, who was drowned in San Antonio in 2018 (middle) ; and Carla Patricia Florez-Pavón, 26, who was strangled in Dallas (top right).

“Looking at a concentration where a lot of the violence is happening, you start noticing certain patterns,” said Cruz. “Looking at Texas, all these women were [murdered] between 2017 and 2018 and all were younger than 30. They ranged [in age] from 26 to 28, and the crimes, the way they’ve been processed or looked at, one of them was a victim of what they consider a serial killer, which was the last one I had on in that piece. He was a border police and murdered four women, and Janelle had become the last one. There was another case of Kenne, who had been drowned and pushed. The man was arrested, and I believe the case was dismissed. Because of the law, it’s not considered a hate crime. They didn’t know each other, but I’m seeing there was a pattern in certain areas and I wanted to put them together. They are posed after high fashion and brought together to create a certain composition, so all the vegetation in the back is from plants native to Texas.”

Cruz created this painting as a memorial to the black and brown trans migrants and asylum seekers escaping the violence in their home countries who have become victims of rape, exploitation, and assault during their journey to the United States.

“I call her the diva,” said Cruz. “I was really thinking about Whitney Houston in the early years, The Bodyguard, “Queen of the Night,” that whole lusciousness, that idea of arriving, this gala, this ball. She’s such a force, I wanted her to be center stage, very powerful. She’s of the future, she’s taking us with her. She’s dressed in country cotton, which is the very southern cotton with a little stitching at the tip, which is also used in the Caribbean, any warm climate. I wanted something that is very familiar for certain people. She is completely covered, and if you look very carefully, under one of her folds, there is a locket. When I started working on the project, I talked about those that are unseen, those that are not talked about, those who are misgendered, or those where their family refuse to use their chosen name, so therefore embracing them. She’s like, I’m taking me with you, I carry you. It’s close to the heart with the idea of carrying you, being close to you. It’s the way we carry tokens of our families.”