An event hosted by the Rainforest Foundation at the Ford Foundation illuminated the next chapter of indigenous conservationism, presenting the knowledge of local communities and new photographs by Laurence Ellis.

In the fight to curb the destruction of the climate crisis, the Amazon rainforest is a vital battleground. It’s one of the largest carbon sinks, extracting carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and keeping the planet cool—an air conditioner of sorts for our Earth. Yet, for centuries, the Amazon has been eroded by colonizers, loggers, and drug cartels that drain the life from the forest without hesitation.

The consequences of losing this vital global resource are ever more apparent following the mass destruction caused by the Amazon rainforest fires, but efforts to conserve these lands often ignore their strongest advocates: indigenous communities. About 25% of the Amazon is indigenous land and 35% of intact forests are managed by indigenous leaders. But less than one percent of private and public investments go toward indigenous conservation solutions which are demonstrably more effective than those of corporations. Indigenous communities have a strong track record of sustaining and growing the forestation in their territories—and as the Rainforest Foundation rightly notes, “If tropical forests could be saved from behind a desk in a glass office building, it would’ve happened years ago.”

Deforestation prevention that foregrounds the rights, protections, and empowerment of indigenous communities was the central focus on Tuesday, at the Rainforest Foundation conference, “Scaling up effective community-driven solutions to protect the rainforest and tackle the climate crisis.” The event, hosted at the Ford Foundation, featured panel discussions with indigenous community leaders—plus one moderated by Alec Baldwin—and an interactive exhibition highlighting Laurence Ellis’s photographs of the Peruvian Amazon from the forthcoming Fall/Winter 2019 issue of Document.

The aim of the event was to spotlight an on-going initiative that started around 2015. That initiative empowers indigenous communities with new technologies and a procedural framework to ensure their efforts to conserve their forests achieve maximum results. The four-step system, which was developed by the Rainforest Foundation, the Indigenous Organization of the East Peruvian Amazon (ORPIO), and the World Resources Institute, works relatively simply:

1) Indigenous technicians work in regional hubs to collect and analyze satellite data which alerts them of possible deforestation.

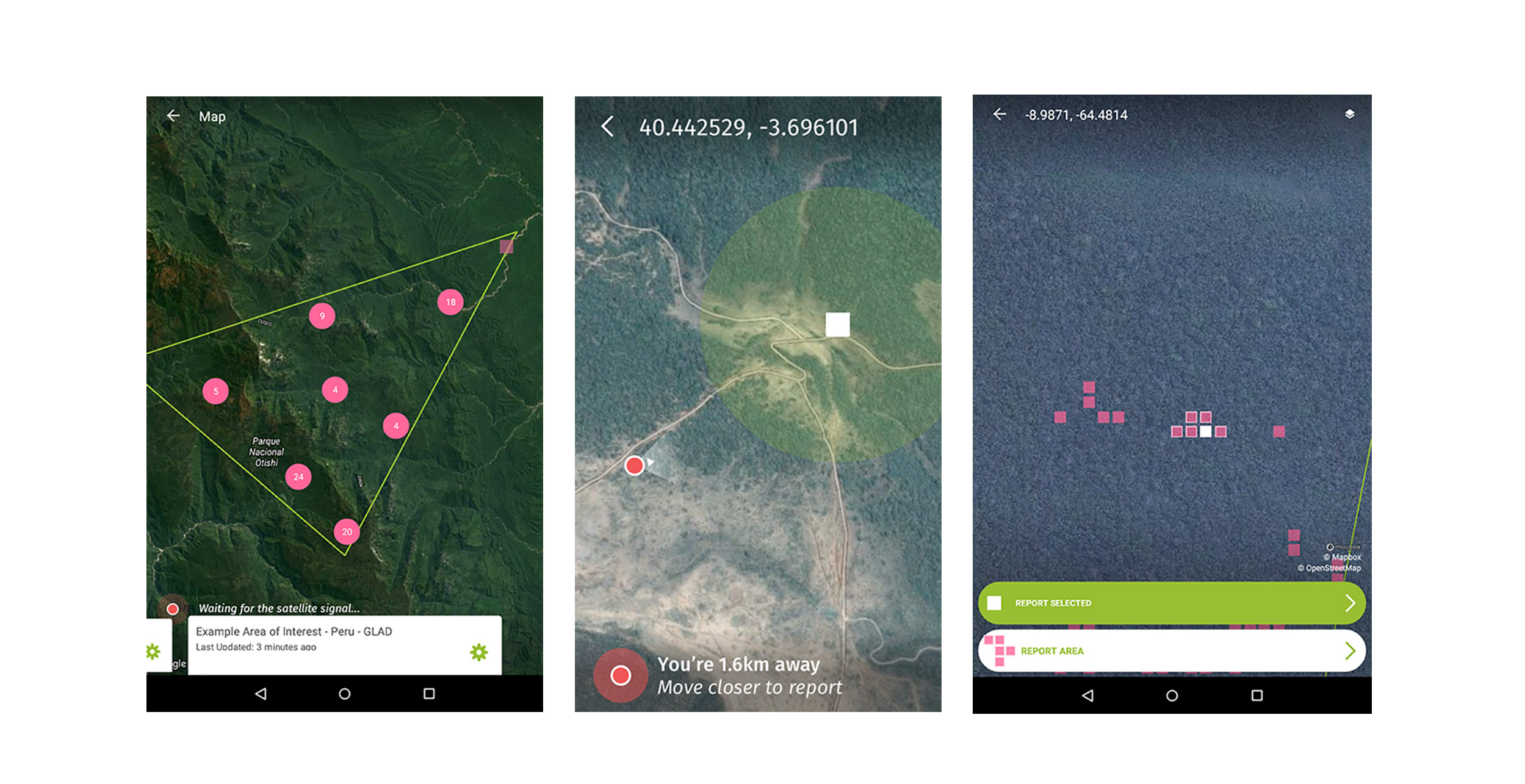

2) They send this information to “community forest technology monitors,” three to five elected local representatives, who use a smartphone app called Forest Watcher to locate the areas in their territory where deforestation may be occurring.

3) These representatives then go into the field with their team to investigate the area, on foot and using drones, to verify the alert with photographs which the app Forest Watcher geotags and catalogues.

4) Monitors then report their findings to their community assembly, the highest authority, which determines as a group whether the deforestation is authorized or unauthorized. If it’s the latter, action is taken—either through internal governance systems or by delivering the findings to the proper authorities.

Between early 2018 and May 2019, researchers at Columbia University performed a study on the impact of the program. Tara Slough, the principal investigator of the study, delivered preliminary findings during Tuesday’s conference. Slough and her team found that not only did the surveyed communities participate in monitoring at high rates, but that their monitoring activities increased over time, suggesting that maintaining and scaling such programs is viable long term. The core of the message was clear: deforestation prevention is vastly more efficient when indigenous people are empowered and their territorial sovereignty is respected.

However, many indigenous leaders like Betty Rubio Padilla and Francisco “Poncho” Hernadez, who are regional field representatives and ORPIO technology coordinators working in the Loreto region of Peru, stressed the importance of labor this system requires in addition to the technology. Day-long treks into areas populated by coca farmers or other dangerous trespassers can make enforcement of land rights incredibly risky.

One oft-cited advantage of these technologies was their cost. Using this program, the Rainforest Foundation prices saving one hectare of forest at $5 and preventing one ton of CO2 from entering the atmosphere at around $1. Community monitoring is an incredibly cost-effective funding model for deforestation and climate change mitigation—if you ignore the human cost.

Land defense is one of the most deadly forms of resistance. The most recent statistics in 2017 estimated that nearly four land defenders were killed per week, with most of the deaths occurring in South America. Oftentimes, illegal deforestation is carried out by outsiders from neighboring Colombia and Brazil, who seek to plant coca to produce cocaine. Field organizers put their lives on the line every time they follow up on alerts to verify land loss.

Nonette Royo, executive director at the Tenure Facility, correctly pointed out that there are many places where environmental and economic impact statements simply fail to adequately capture what’s lost when an acre of forest is gone—or what indigenous land defenders are putting on the line in service not just to the Amazon, but to all of us, who rely on the forests. And despite their sacrifice, indigenous-led efforts to combat climate change by defending the Amazon are still met with violent resistance, often by these communities’ own governments.

Michael McGarrell, an indigenous activist from the Amerindian Peoples Association of Guyana, illuminated the stakes of the on-going project during a panel presentation. “It’s about time [our governments] recognize the value of our indigenous knowledge which has allowed us to sustain our forests for many generations,” he said. “This is not just for us indigenous people. This is for all of us.”