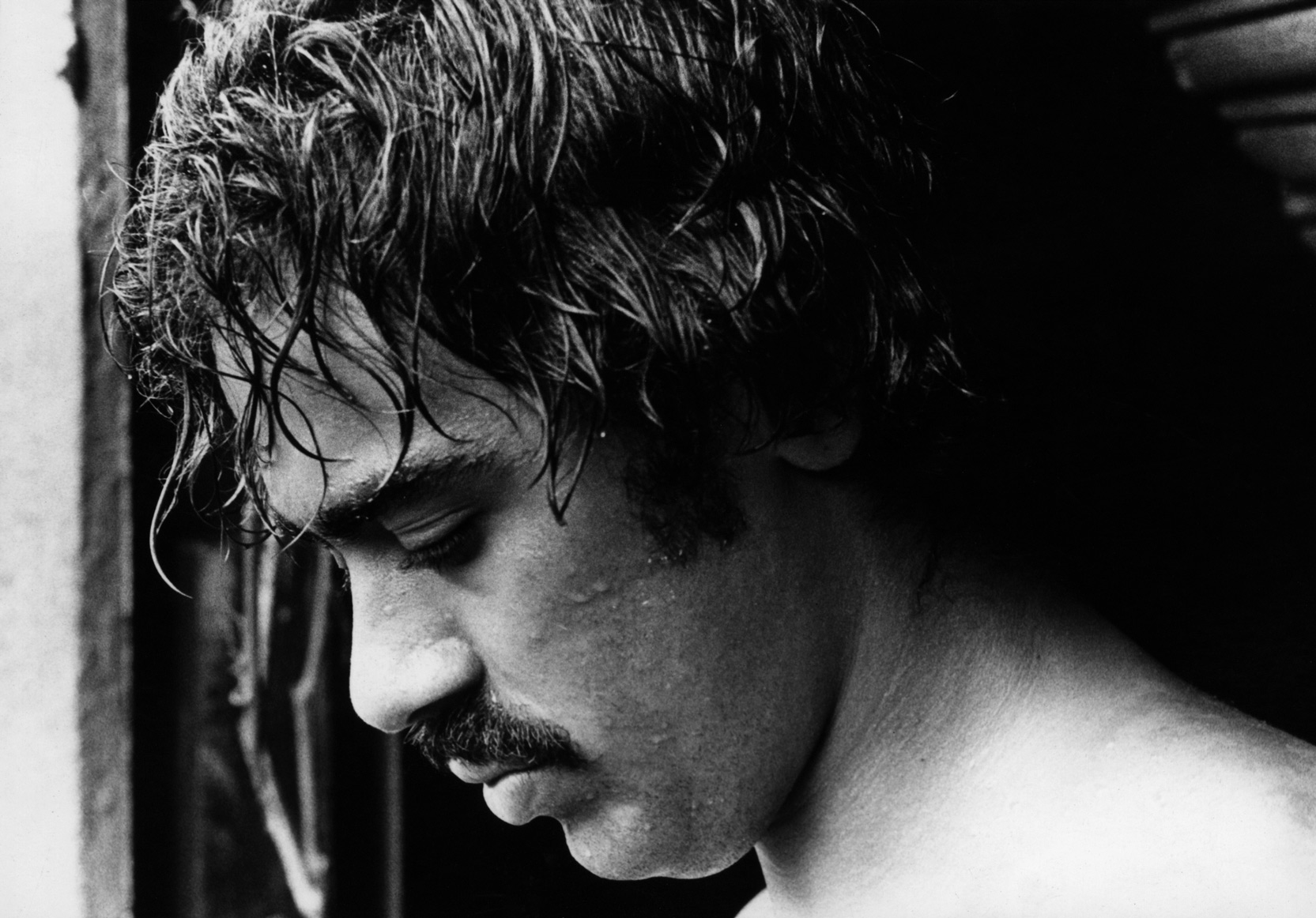

The Bronx-born photographer never achieved the success of Mapplethorpe or Hujar, but his images from Manhattan's West Side Piers illuminate a forgotten era.

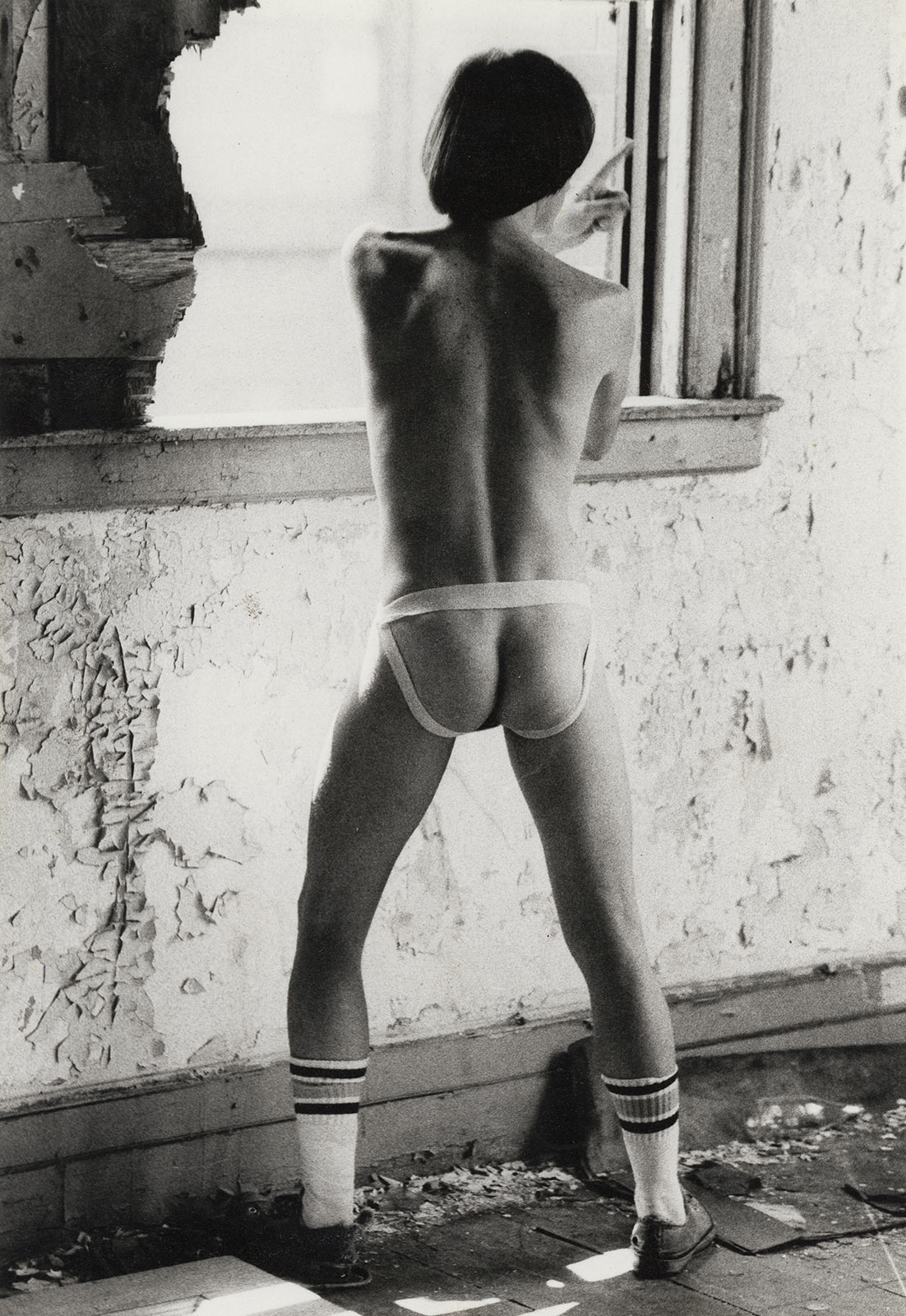

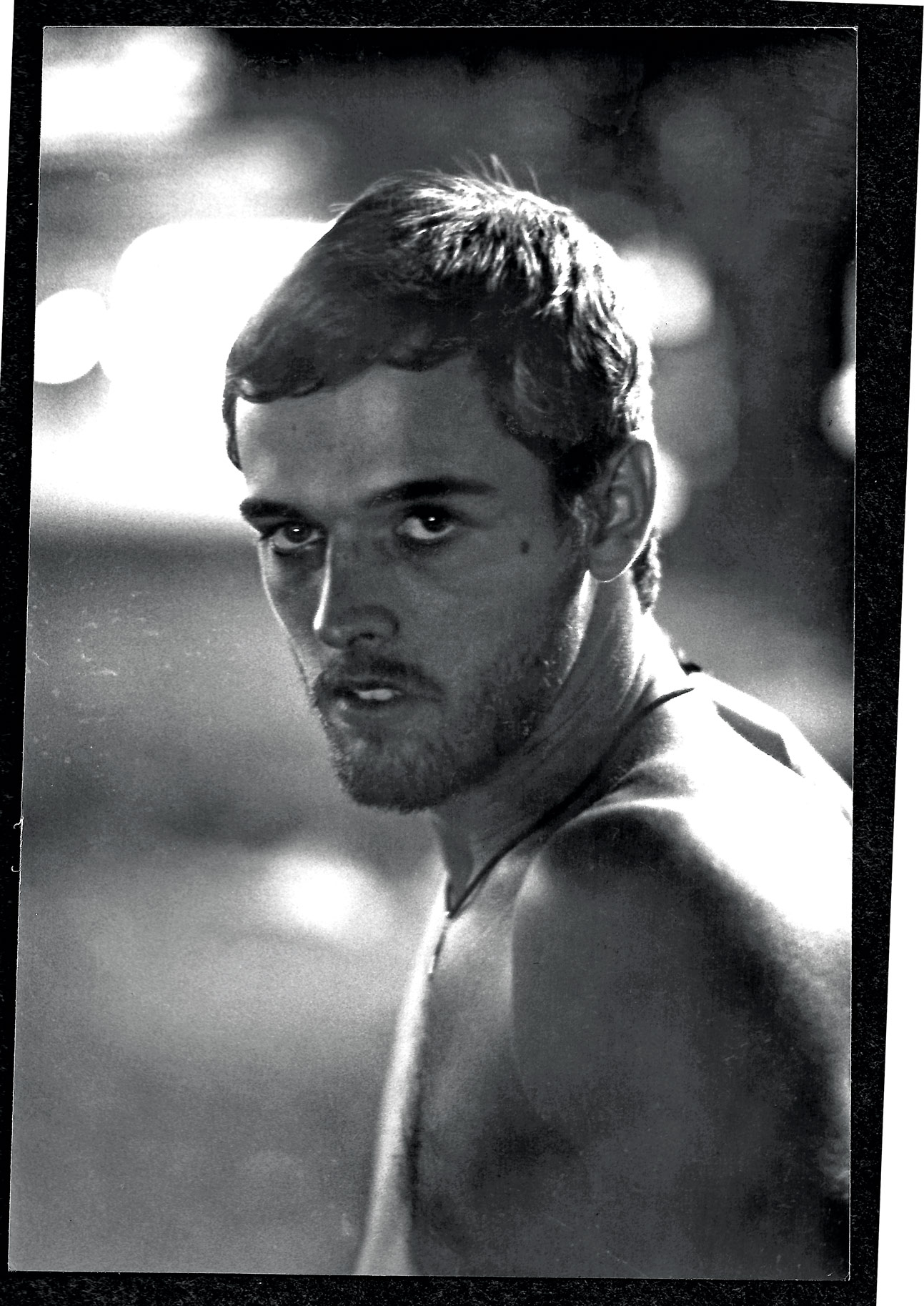

In the brief window between the Stonewall Rebellion and the advent of AIDS, New York City became a wonderland for the sexually adventurous. As the city teetered on the brink of bankruptcy, the spirit of anarchy arose among the dilapidated ruins of the bustling metropolis. Raised on free love, a new gay underground emerged in the bars and clubs, as well as on Manhattan’s West Side Piers where encounters with rough trade-in derelict warehouses flourished in broad daylight.

From 1975 to 1986, African-American artist and Bronx native Alvin Baltrop (1948-2004) dedicated his life to documenting this little-known chapter of gay history, amassing a singular archive of work that preserves the era perfectly. At a time when the nearby Meatpacking District still ran red with fresh blood, Baltrop captured the grit, grime, and humanity that thrived in an enclave of illicit pleasures of the flesh.

Largely excluded from the art world during his life, Baltrop is finally receiving his due with a major exhibition, The Life and Times of Alvin Baltrop, opening August 7 at the Bronx Museum of the Arts. The museum is home to the Baltrop Archive, a trove of personal documents, photographs, and ephemera that provides a first-hand account of the challenges he faced throughout his life.

With the understanding that the artist was just as important as his work, Sergio Bessa, Director of Curatorial Programs at the Bronx Museum, has assembled 120 works that illuminate Baltrop’s unique ability to be both participant and witness to an era that has all but disappeared. “I was fascinated by how the city was falling apart but the outpouring of creativity was remarkable. This show can inspire communities in crisis,” Bessa says.

Baltrop took up photography as a teen and supported himself with odd jobs that included working at the Stonewall Inn prior to the 1969 uprising. He enlisted in the U.S. Navy in 1969, serving as a medic until 1972, and nurturing his love for photography by creating a makeshift lab using medical equipment.

“The photographs he made in the Navy were a revelation,” Bessa says. “He was photographing the landscape, along with intimate scenes of his comrades inside the cabin or on the deck sunbathing—as he would later do on the Piers. His work from this period already conveys the visual style that distinguishes his mature work: intense sexual desire encrypted into a chaotic network of signs.”

When Baltrop returned to New York, he enrolled in the School of Visual Art to study photography. Though it is unclear exactly how he learned of the scene at the Piers, his work as a taxi driver certainly kept him hip to what was happening on the scene.

The Piers first came into vogue after a section of the elevated West Side Highway collapsed between Little West 12 Street and Gansevoort Street in December 1973—the site of Pier 52, which would soon attract the likes of artists like Gordon Matta-Clark, who used the discarded space as a site for artistic interventions. In the years that followed, artists including Peter Hujar, Robert Mapplethorpe, and David Wojnarowicz would be drawn to the Piers to make art of their own.

Like his contemporaries, Baltrop was inspired by the radical energy of the space—but his perspective was much more nuanced, ambiguous, and unconventional due in part to his background. “His mother was very religious and at some point, it seems she discovered a lot of his photographs of naked men and threw everything out. When she discovered he was bisexual he had to leave home,” Bessa says.

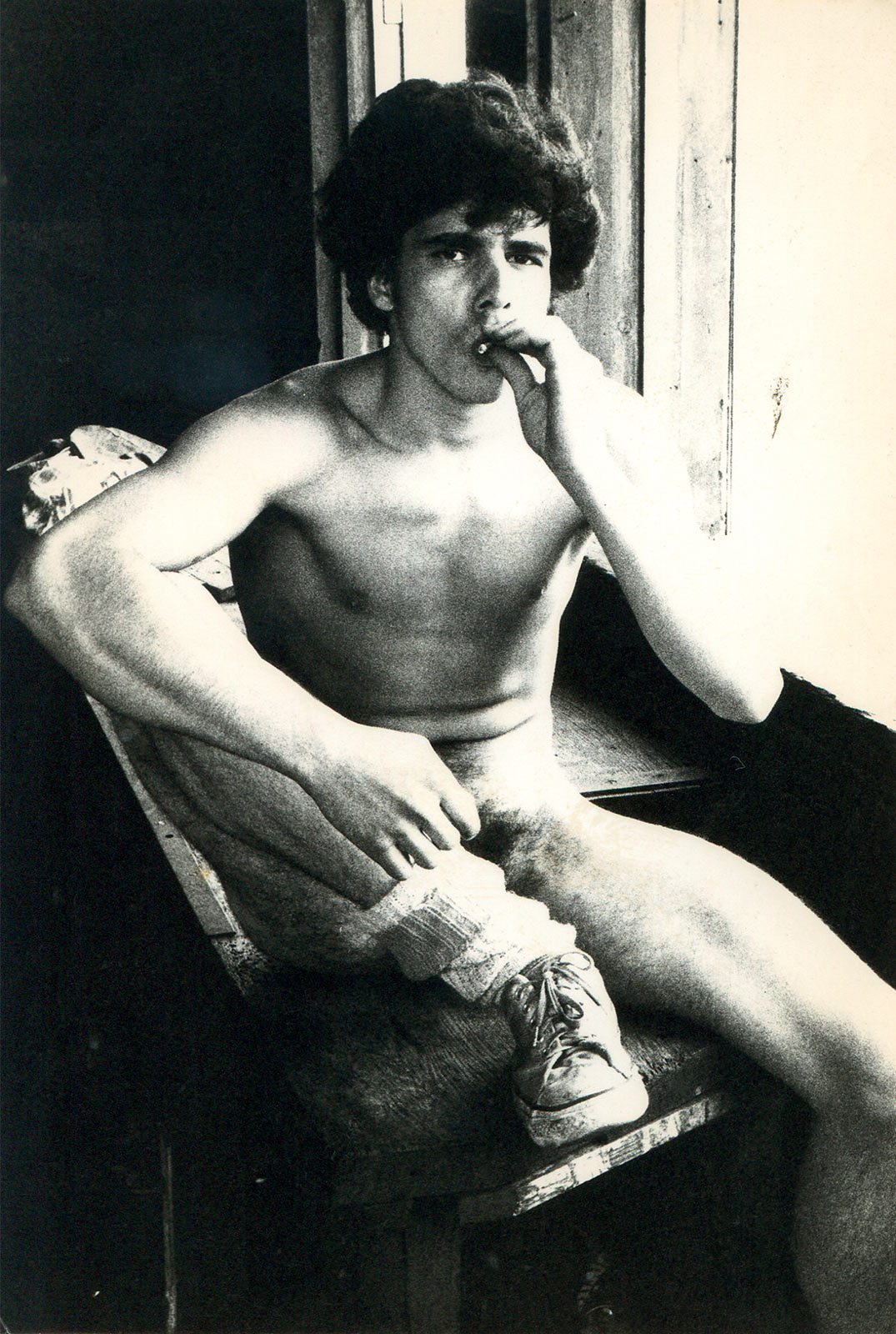

In the 1970s, sodomy was still illegal in New York State (the laws were not repealed until 2000). Though the Gay Liberation Movement tore the door off the closet, those who engaged in homosexual acts were still outlaws. The Piers attracted those looking to escape the confines of “civilized” society, enjoying the thrill of living on the edge and engaging in anonymous trysts.

“Cruising areas for gay men always happened but by the ‘70s, it was happening on a much larger scale. People were not hiding in the Ramble in Central Park during the evening; this was going on in the center of the city during the day,” Bessa says.

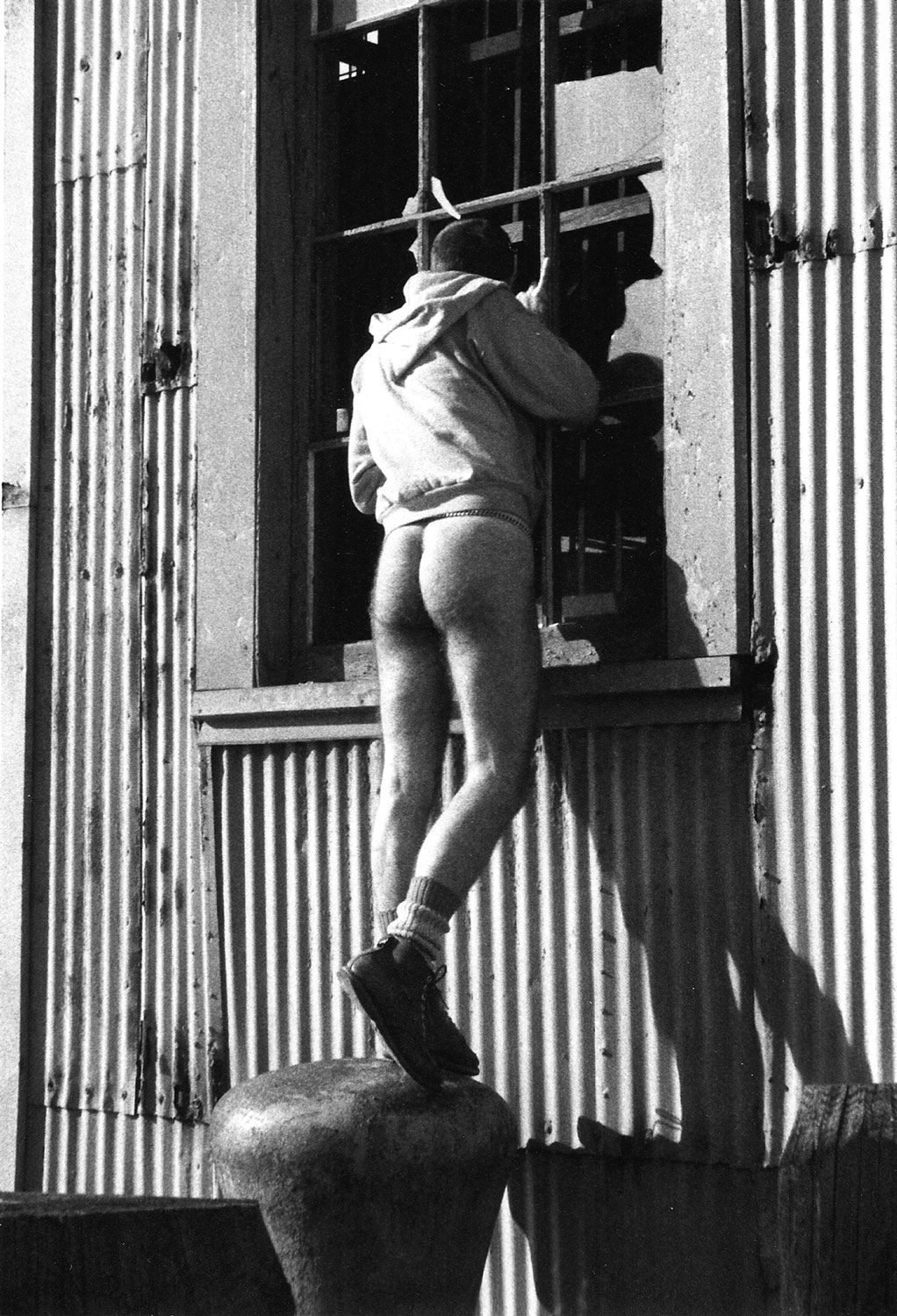

“Baltrop got in there at the beginning. He quit his job as a cab driver and bought a van to become a mover so that he could afford to spend more time at the Piers. He saw his work as an archive. Sometimes he would spend days sleeping in the van just waiting for opportunities to get some of the shots.”

Baltrop’s dedication to his subject fosters work akin to Danny Lyon’s Bikeriders, or Stephen Shore’s Factory photographs, continuing the practice of the New Journalism that sought out understanding through immersion into the scene. In Baltrop’s work, objectivity and subjectivity merge into theater writ large.

“In the Navy, he developed a sense of drama through juxtaposition of the intimate and the landscape that he applies to the Piers,” Bessa says. “There will be a sequence of three or four images that show two guys coming, undressing, and getting on the floor to have sex. At the same time, you have lots of photos where his main concern is the conditions of the environment.”

Baltrop took his desire to create a 360-degree view of the scene to the ultimate height, going so far as to don a harness and hang himself from a beam on the top of a building in order to capture the scale and scope of a new sexual frontier nourished on the waterfront. “He was like a hunter, in there for hours until something happened, and then he captured that,” Bessa says.

For all his careful observations, Baltrop was not a voyeur. “His gaze had a lot of ambivalence. The way he looks at couples is more about desire and longing. His photographs are not pornographic at all. There is a lot of dignity in them,” Bessa says.

“I think he was fascinated by what was happening at the Piers and he participated but he also cared for the people. There are stories about him taking kids to be tested for STDs. The values of his mother seeped into his personality.”

“The Life and Times of Alvin Baltrop” is on view at the Bronx Museum of the Arts through February 9, 2020. A catalogue of the same name is published by Skira, and “Alvin Baltrop: The Piers” is available from TF Editores.