Can Maison/0—an incubator project from CSM and LVMH—convince luxury brands to be more green?

For the past thirty years or so, Central Saint Martins has been the nucleus of emerging fashion designers. The steady stream of alumni from the London-based university is as impressive as they are frequent; from Alexander McQueen to Stella Macartney, they pique the attention at the right shows, they go on to direct major fashion houses, and routinely wreak creative havoc that ripples through the decades.

But as the full environmental impact of the fashion industry reaches public consciousness, the next generation of fashion designers from Central Saint Martins must take sustainability into account. The UN reports that the fashion industry is more polluting than aviation and shipping combined, stating that 85% of textiles end up in global landfill. From the raw materials to its colossal waste, the industry needs a sharp and serious wakeup call when it comes to its part in climate change and environmental deterioration.

It’s an issue Central Saint Martins has been trying to embed through every single course. In partnership with LVMH, Maison/0 is an incubator at the university aiming to edge the designers of tomorrow towards a more sustainable future. This year, they’ve signposted the environmental mindset through its graduating courses participating in the 2019 degree show. We spoke to four of the students behind the most creative, insightful, and game-changing designs to see how sustainability in fashion looks—beyond hessian sacks, beige colour palettes, and monotone designs.

One of the biggest challenges when creating sustainable designs is ensuring they’re as desirable as they are practical. Elissa Brunato, from the Material Futures course, wanted to create a sustainable sequin. “We wash our clothes in machines. Think about what happens when one or two sequence falls off a garment,” she tells me in the foyer of the university. “Now think of the scale that this sort of creates on a larger level. We’re starting to look at micro plastics entering the oceans, not just from factory floors being swept out into the streets, but in the more global context of domestic washing.”

Brunato’s bio iridescent sequin uses naturally abundant materials to create shimmering structural colors. “Think of a beetle wing,” she says. “It creates iridescence by having a structure that allows light to come in [and] bounce out as a rainbow spectrum for our visible eyes.” With no chemical colorants added to her sequin, Brunato has managed to use structure to recreate a pattern and color previously made using oils and plastics.

Like all the other students I spoke to, Brunato wasn’t interested in designing something sustainable just for the sake of it. Meticulously researched hard data played just as big a role in her creative process as aesthetics. “The statistics are hard to find, but when I last looked on ASOS, out of 75,000 garments over 1,000 are sequined,” Brunato told me before going on to explain the average dress can have anything from between 2,000 to 5,000 sequins on it.

The physical prototype Brunato created during her studies is just step one in a long journey to get the big fashion houses to adopt it: “Rather than trying to validate if this is aesthetically pleasing, or it meets the standards of haute couture, I’ve been gaining a lot of that feedback for myself and for my thesis through [the] industry. Stella McCartney was a collaborator, and I asked people from factories whether they want to work with it, getting real industry feedback and not making this just because I think it’s beautiful.”

But we don’t just need to create new things to engineer our way out of the impending climate disaster. Daisy Yu is about to graduate from the undergraduate womenswear course. Her graduating collection uses leather scraps to create an entire series of garments. “Because the material has no grain I can use all the offcuts,” Yu explains. “But leather is also one of the materials where you can’t make a mistake. Every hole or mark stays there.”

Using traditional Chinese braiding techniques, her approach to the material utilizes it’s supple and luxurious features in bold and structural designs. For Yu, working with a restriction like leather offcuts isn’t a hindrance; it’s another creative restriction to work with. “I would have never of put some of the colours together like I have,” she says while walking me through her work. “But because I was restricted by the colour pallet, I made it work.”

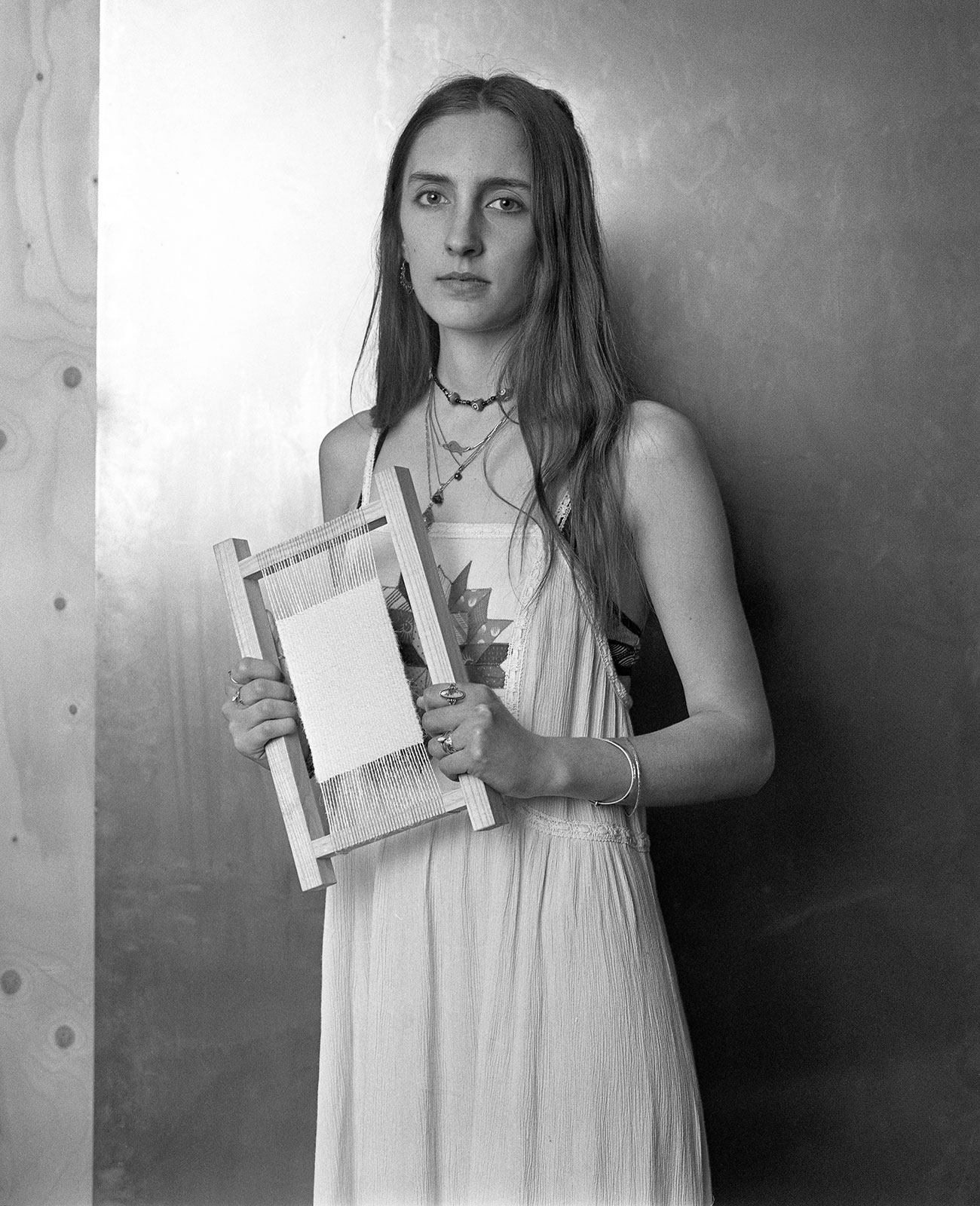

That ability to use an obstacle to break through creative boundaries is a motif that runs through the graduates’ work. The fabric behind Benjamin Benmoyal’s collection has been woven out of the tape from old cassettes. The fact that it’s literally made out of music isn’t a surprise; his final creations look like something the funk band Parliament might wear, ՚70s throwback coats and jumpsuits with disco wigs. “I learnt how to do it myself,” Benmoyal says. “I used YouTube and a teacher from Chelsea, who helped me learn how to weave. It took one year to make 90 meters using recycled yarns and cassette tapes.” Sourcing the VHS tapes from his childhood from Ebay, he dyed them by removing the original color and replacing it with paint. “Fashion is not art,” he goes on to tell me. “You have to produce. So I partnered with a Parisian company and we have now created the fabrics together.” Benmoyal says he does care about the environment, but he never intended to “save the world” with his collection; he wanted to test his abilities: “Because when I limit myself, I become more creative,” he adds.

There are many approaches to creating sustainable garments, be it in the design, the fabric, the production line, or all three. Natalie Spencer, also in the Material Futures course, took inspiration from the biological cycle of the circular economy to create a new type of wool.

“I tried celery, I tried nettles—anything that was a fibrous plant,” Spencer explains, “But I found pineapple worked the best.” Erecting collections station sat juice bars across London, she used a metal spoon to help scrape away excess material and extract the fibers, using product many juice bars throw away. “Ideally everyone would compost the fruit,” she says. “But most of the time it just goes into landfill.”

It was important to Spencer that she create a material designers would actually want to use. “The hardest part was making it soft,” she says. “I tracked down a company in Switzerland who makes biosoftteners from plant seeds.” Her white fluffy wool isn’t bleached either: “The wool I use comes from the natural color, natural form and natural state of the original fiber.”

Like all of the students, the next step in bringing Spencer’s creation off the ground is making it easy for the industry. They know developing an idea is one very small part of getting their it picked up by the wider manufacturing chain. Every one of the designers I spoke to was trying to take their products to the next level. Yu had 3D printed shoes that matched her collection and incorporated her repurposed leather and Brunato was testing how long it takes for her sequin to degrade. The most important thing about their ideas is that they’re viable; they’re based on a bedrock of research and collected knowledge, giving them life beyond the graduate shows—the truest embodiment of what it means to be sustainable.