Photographer Markn captures the artist's contemplative and explosively kinetic process.

Japanese calligraphy, also known as shodo, might call to mind the traditional hanging scrolls that decorate Kyoto temples. But the art form—much like tea ceremonies and Noh theater that are also strongly connected with “Zen”—has been greatly developed since the old days. The artist and architect Isamu Noguchi incorporated calligraphy into his early artwork most famously in his sets of figurative drawings from 1930, and we can see elements of Zen and calligraphy abundantly scattered through his later sculpture and garden works. From the point of view of contemporary art, Japanese calligraphy can be seen as a documentative performance art within physicality and spatiality.

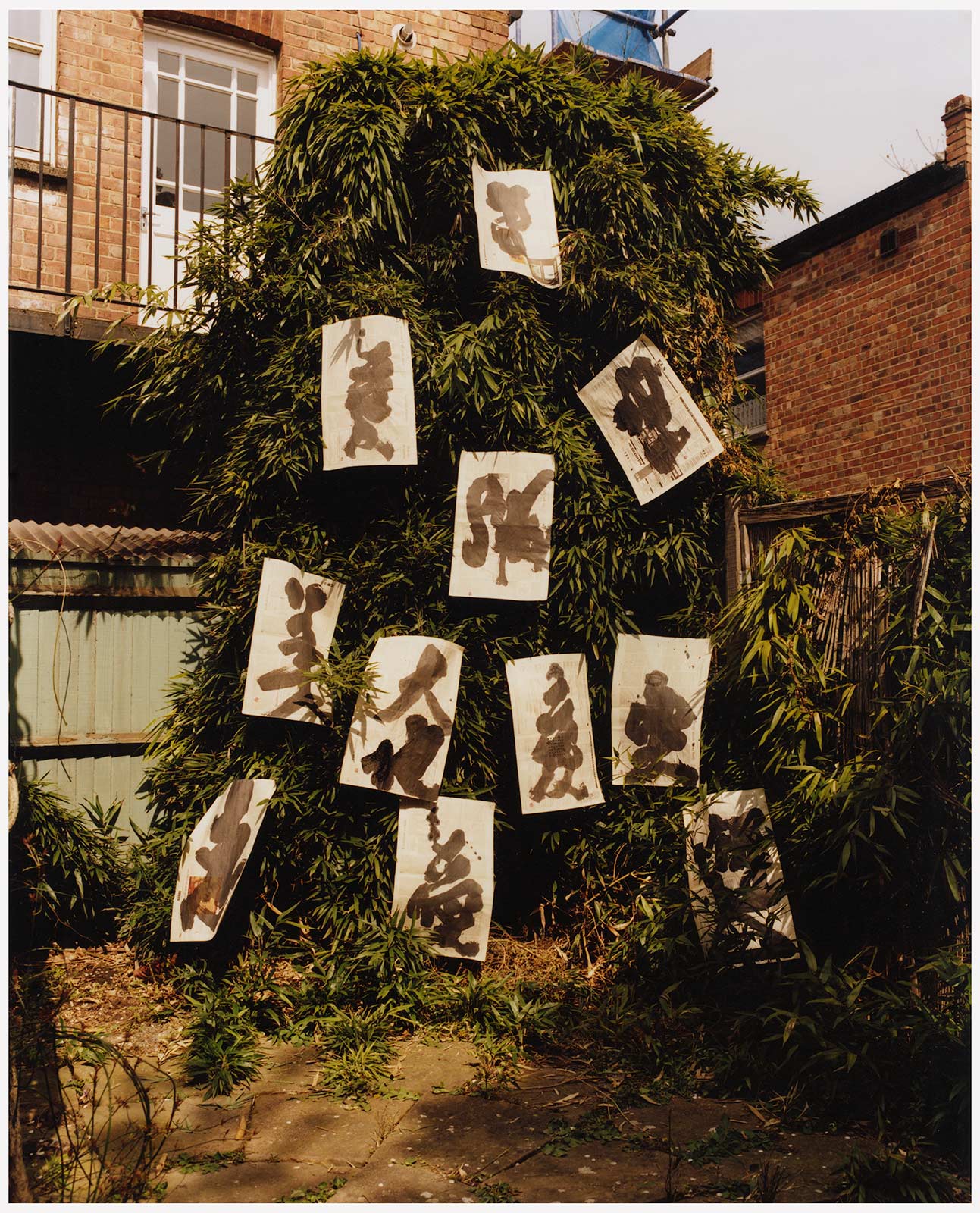

Daichiro Shinjo is a young artist bringing old-fashioned calligraphy into the future, pursuing unconventional light and contemporary expressions. Born in Okinawa’s Miyako Island, at the southernmost tip of Japan, Shinjo graduated from Department of Space Design at Shizuoka University of Art and Culture before moving to London to further develop his art. Last month in London, Markn photographed the contemporary shodo artist and his girlfriend, Aoi Inagaki, capturing moments of uninhibited emotion and intimacy. Hiroshi Hashiguchi interviewed Shinjo about his self-expression, questioning reality, and creating art amidst political turbulence.

Hiroshi Hashiguchi—Why did you choose calligraphy among many expressions of media?

Daichiro Shinjo—I started calligraphy when I was a kid, more than 20 years ago. I went to calligraphy school almost every day; it was a part of my life, and I realized I was naturally familiar with calligraphy. At university, I majored in architecture, but I did not have the opportunity to learn other expressions, so I felt that my breadth of self-expression did not expand.

Hiroshi—Japanese calligraphy can express the world even with one character. Is there any standard for selecting characters to write as a work?

Daichiro—I have never considered the standard. In retrospect, I may have avoided negative words and letters unconsciously. As I spend my time surrounded by various information and events, I think about it and ask myself about themes that appear spontaneously. This determines the words and characters I write. Of course, there are also letters and words that are decided the moment I am writing, which forms the basis to write the same letter consecutively.

Hiroshi—Are there moments when you feel a difference between expressing through Japanese calligraphy and expressing through other forms of media?

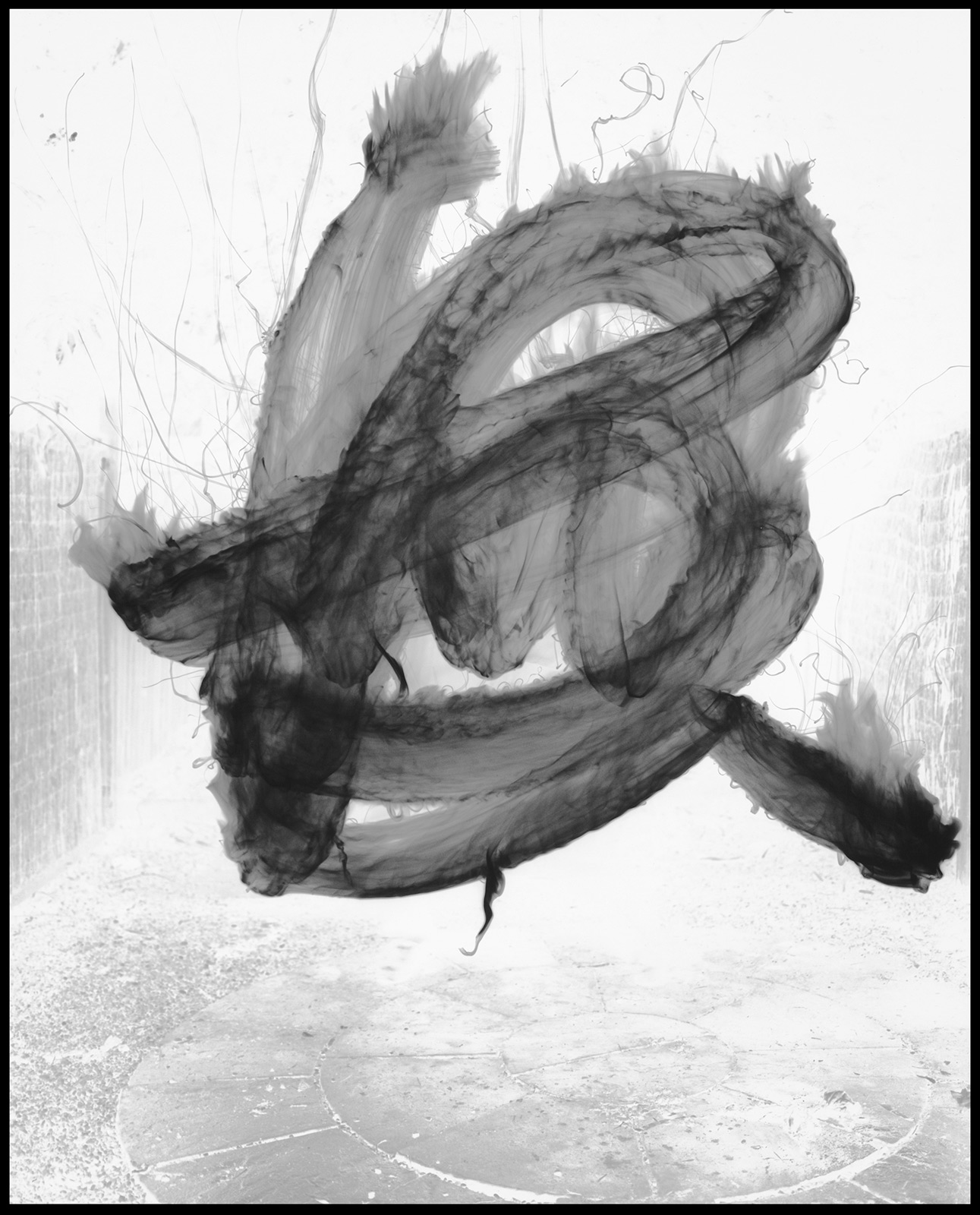

Daichiro—I feel the difference in the time it takes to produce. Writing is instant, very physical. Because it takes less time, I think it is a straightforward expression that allows you to shape the emotions within. Of course, the process from preparing the ink to the ink drying is not instantaneous. I have also created new works with layers of text on what I wrote in the past, but I feel that writing the same text again and again creates a depth of expression. Recently, I feel my process is closest to photography. It’s almost as if a moment captured through photography is similar to writing drawn on paper. I think that calligraphy is an intuitive media that is easier to understand through feeling. In Japanese education, calligraphy is compulsory. There is also a belief that written letters are just as letters that have common universal meaning, and therefore are not a form of art.

Hiroshi—You also draw abstract patterns. What forms the inspirations for these patterns?

Daichiro—The Zen philosophies are directly influential. In my grandfather’s temple I used to imitate the drawings of monks representing the Edo period. In particular, the writings of Sengai’s “○△□” have been greatly influential. It is not a character or word that has been captured, but a work created through questioning and confronting oneself for a long period of time, and the patterns are a result of this—unlike words my works of abstract pattern, they can be made through multiple layers of ink. It is a series of continuous accumulations of ‘writing acts.’ It’s a slightly different approach from writing characters. I keep chasing the black of the brush tip on black as if taking a long breath. It is not a search for something, but it is an action to approach ‘nothingness’ or a depth of time and infinity.

Hiroshi—In Japan, traditionally, there is a room in a house that has a space for calligraphy art. Your work captures a sense of meaning in a space and challenges the conventional codes of the calligraphy seen in hanging scrolls. What are your thoughts on conventional calligraphy art and your art?

Daichiro—I think that it is necessary to inherit traditions, which also brings questions and fears about people that follow tradition. But I think it is necessary to look at these things. In that sense, while I search for my truth, there are quite a few repulsions that I wish did not exist. I do not want to be a part of an absurd society full of crazy information. A character is born, a word is born, and a person lives by adhering to the symbol. A person unconsciously clings to words and limits themselves for many reasons. However, we cannot live without information…I want to be skeptical of everything and to deal with contradictions between myself and society.

Hiroshi—Are you thinking about expanding into another media in future activities?

Daichiro—I am interested in photography, and I often visit photo exhibitions. A photograph visualizes the moment in front of you and similarly calligraphy visualizes the moment of your mind. When both elements of time and space work, I feel that I come across strong expressions.

Hiroshi—How do you feel about creating in a foreign country where the characters in calligraphy are not understood? What kind of reaction is interesting for you?

Daichiro—I wanted to see the island where I was born in Japan from a distance. Being born on a small island, I was able to look at myself and the island every time I moved away. I wanted to go to places with different languages, lives, history, and cultures. I have not even been in London for half a year, but I feel less restraint and attachment, which I am grateful for. However, at the same time, I feel a sense of emptiness that I am only a tourist. I feel that is especially true if you look at the Brexit demonstrations.

Since I have not yet exhibited in London, I have not experienced many reactions. Recently, a British friend turned my work upside down and was looking horizontally at a vertical writing. Such reactions are interesting. Not understanding the letters, he gave me a new perspective. He takes it as graphic and has no attachment or understanding to the characters I wrote. When I explained the meaning of the letters, he reacted ‘Oh, I see.’ He sees it as a symbol. It seems like a sculpture for foreigners.

Hiroshi—The island Okinawa where you are from has been merged with different cultures from China, Southeast Asia, mainland Japan, and the United States through trade, war, and cultural exchange. In addition, you grew up on an island in the environment of Ryukyu Shinto’s indigenous faith. How do you think that the background affects your work?

Daichiro—In Okinawa, there is a lot of change that happens continuously which leads me to question the island’s identity. The human origin and unchanging spirit can be seen in small ritual events in the village. On the other hand, under economic rationalism, the landscape and the political pressure changes rapidly. I feel this environment is connected to expressions that ask questions about reality and realities of society and myself again and again.

Hiroshi—Okinawa has undergone major political changes, and London is now undergoing a similar upheaval. In such a chaotic environment, what kinds of things influence and inspire your work? Also, what is your outlook for the future?

Daichiro—I am inspired by looking at the changing landscape which flows underneath the shifts of power. In London, I walk around the developing city. Political rebellion creates graffiti on the buildings. There is a similar movement found in Okinawa. Because you live in it, you are physically influenced and inspired by all the changes. My outlook for the future is that I want to create stronger and more physical expressions than ever before. As I mentioned, this approach could be something closer to photography. I want to look deeper into my roots in order to create more powerful work.

Hair Kei Takano using Davines. Make Up Mattie White at Saint Luke Artists. Photography Assistant Milly Cope.