'Particular Voices' saw Giard capture America's queer literary giants alongside emerging talents, treating each with a profound sense of urgency.

In the 1980s, photographer Robert Giard decided to travel around the United States photographing gay and lesbian writers. The enormous project saw Giard capture over 600 LGBTQ authors, artists, and activists—casting literary icons (Allen Ginsberg, Adrienne Rich) in an intimate new light and elevating a new generation of rising talents on the brink of success. His plan, ambitiously yet simply, was to photograph everyone.

Particular Voices is as much a prophecy as it is a time capsule of his radical, resilient community. “I am still amazed whenever I open the book to find someone who’s only recently achieved success or whom I met face to face just last year,” Bram says. “It’s as if Bob could see into the future…He was an amazing man, a generous reader who celebrated literature with his camera, a zoologist of queer lives who captured people not in cages or pinned like insects in display cases, but on film. He was our own August Sander, the German photographer who explored the diversity of Weimar Germany in all its classes and professions and bloodlines. Bob’s photographs are a remarkable record of both his community and his own capacious heart and soul.” As Brian Freeman of Pomo Afro Homos says, “No afrosheen, no makeup, nothing to sell, no need to hide.”

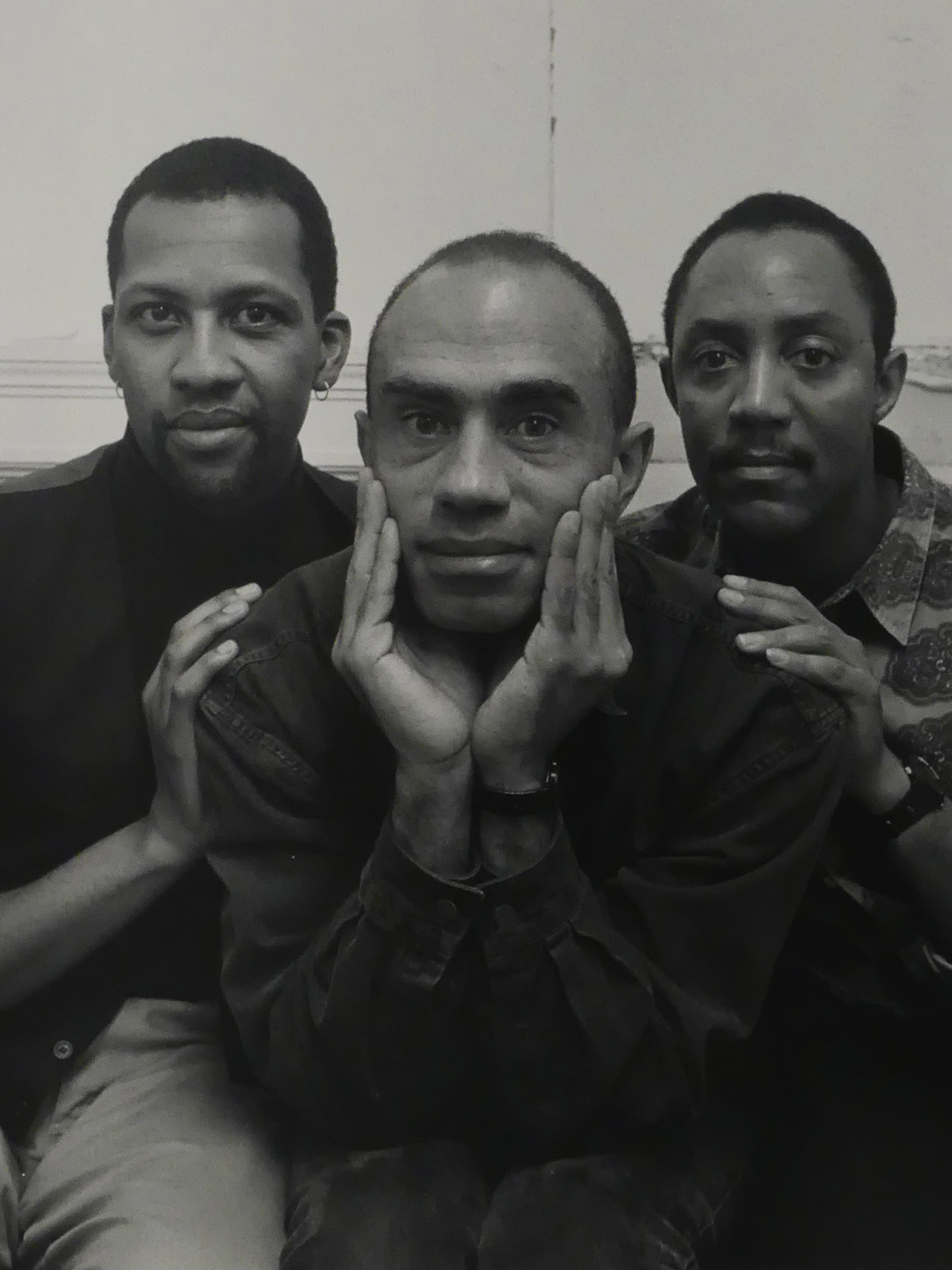

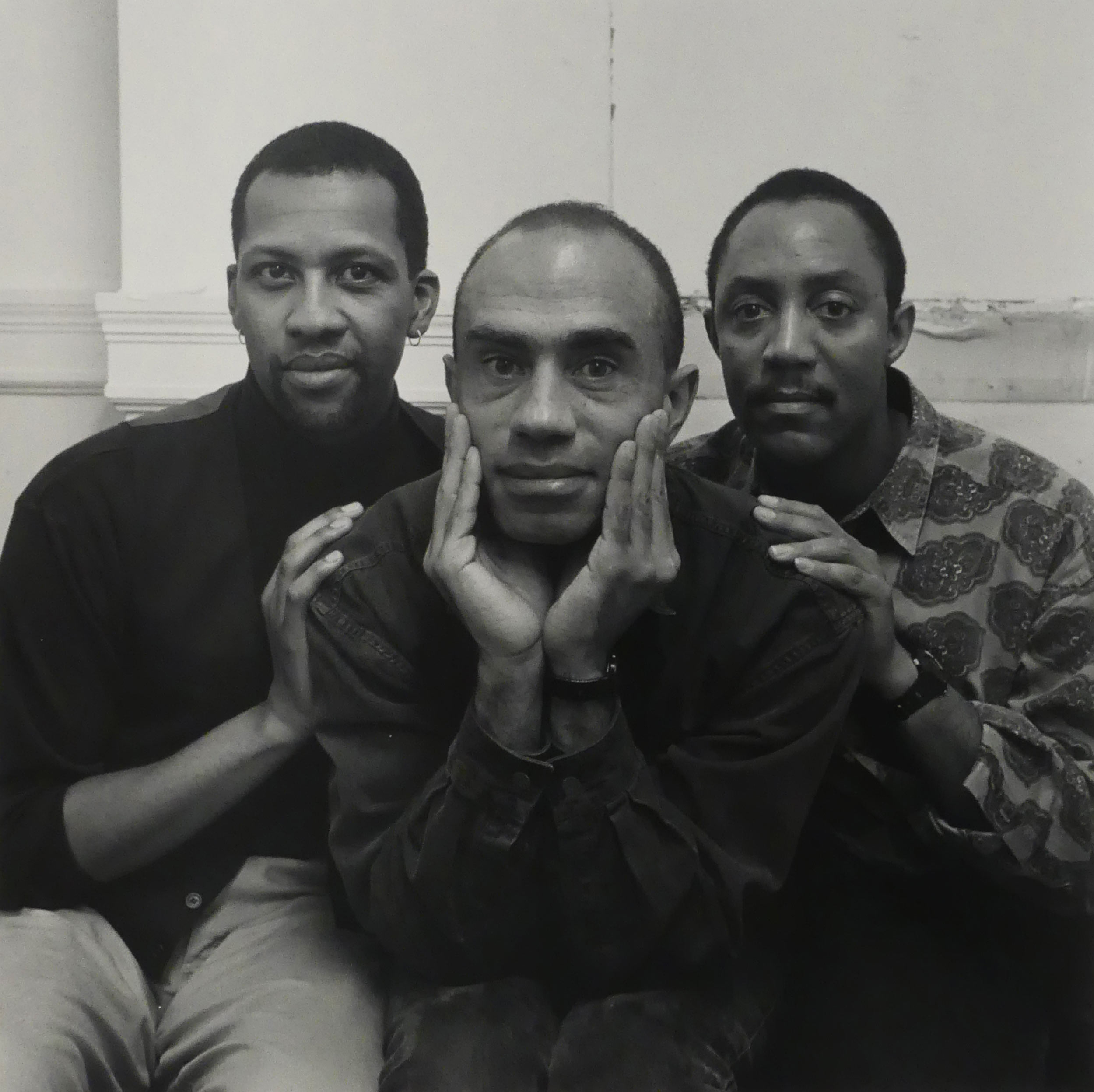

Each portrait contains salient elements of his subjects’ distinct histories and narratives: James M. Saslow’s retired pointe shoes denote the wistful grace of a now-bearded ballet dancer, Joan Nestle proudly holds up a lesbian wall plaque that had formerly adorned the home of Harlem Renaissance dancer Mable Hampton, while Pomo Afro Homos pose with arms subtly contorted in “an intentional nod to vogueing, to our fellow traveller Willie Ninja, and to the roots of performing Black queerness.” Some portraits were created over a full day, others in one magical moment, and all were the genesis of life-long friendships.

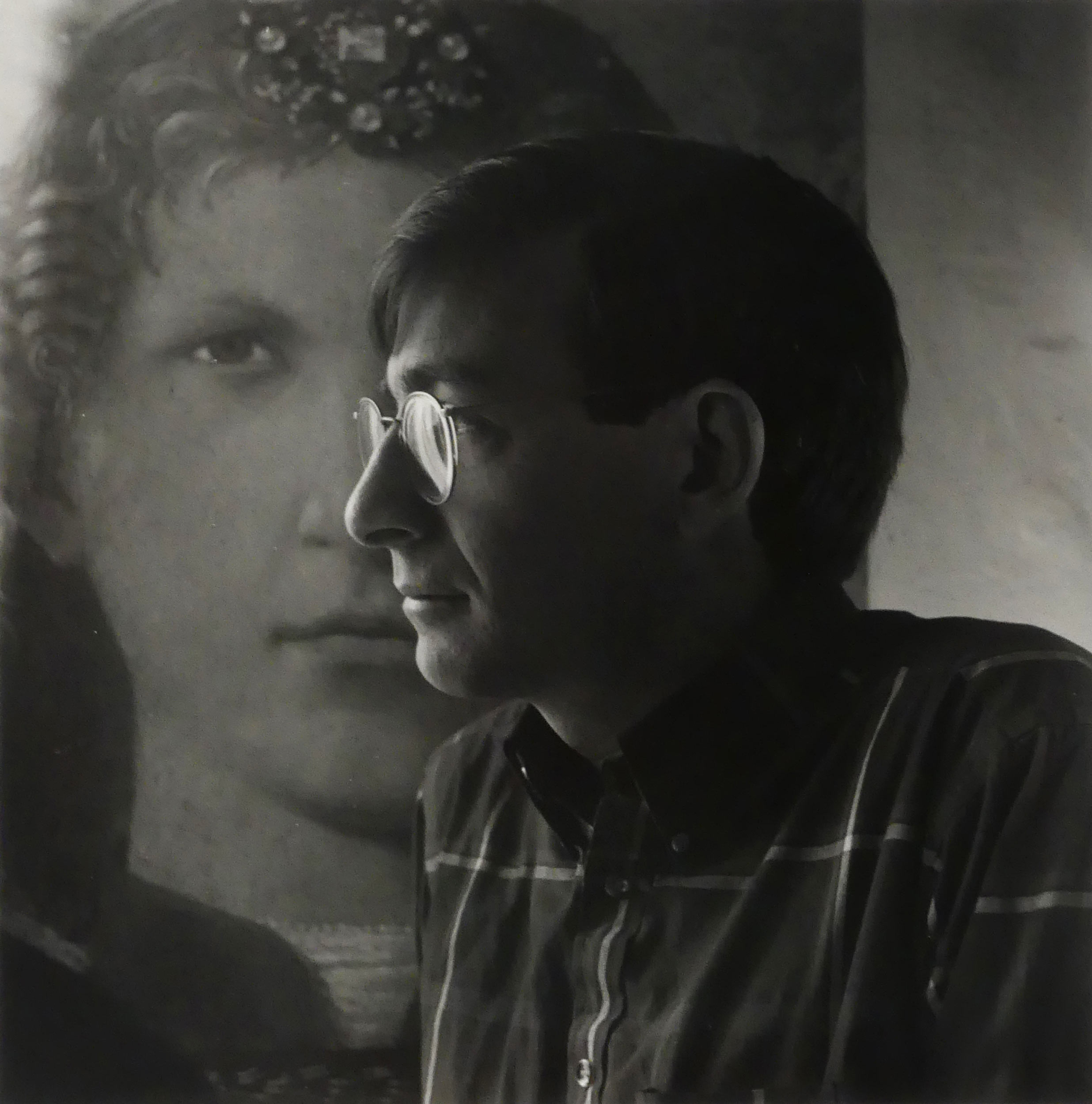

Christopher Bram, author of nine novels including ‘Father of Frankenstein’ (1995) and ‘Eminent Outlaws: The Gay Writers Who Changed America’ (2012):

I first met Robert Giard when he photographed me in 1989. I’d heard that a curious man was making the rounds, photographing gay and lesbian writers. At this point I’d only published two books and assumed he was concentrating on famous people. But one day he telephoned and introduced himself. “Why me?” I asked. “Why not?” he replied and added he was photographing everyone. Was I interested? “Absolutely.”

A few weeks later Bob arrived at my apartment, lugging his bulky tripod and a large-format camera up our five flights of stairs. He was a trim, mild, shy fellow with a wispy beard and sheepish smile. I offered him a glass of water, which he accepted. He then looked around our three-room apartment, hunting for an interesting background. My partner was out–the apartment is small and Draper didn’t want to get in the way.

Bob was pleased that we had windows on two sides: there was plenty of light. I suggested we do it in front of the bookcase, which Draper and I had constructed ourselves–I was very proud of our bookcase. “No, no, no,” he said. He already had too many bookcase portraits.

He opened his tripod in the bedroom and set his camera on it. I lay on the low bed, trying to look comfortable. Bob used natural light and his camera required long exposures, like something used by Matthew Brady. I needed to be perfectly still. He took a few shots but didn’t like what he saw: the white security bars on the window made the place look like a mental hospital. Bob stepped lightly around the apartment, looking for a better location.

All this time we were talking, not about photography but about books. “What are you reading?” he asked. “Have you read so-and-so?” “Yes. And I liked it very much. But I like his new novel even more.” “Really? I’ll have to read that too.” At first I thought he just wanted to put me at ease, which he probably did. But I love to read, as did Bob. Soon we were happily sharing book titles, recommendations and warnings, while Bob fumbled with his camera and tripod. We began with gay fiction but moved on to history, travel and biography, gay and straight.

We ended up in the kitchen, a small white space full of light from the window over the sink. Bob posed me in front of a poster Draper had bought in Italy, a detail from a Piero della Francesca fresco: a beautiful angel. “A study in contrasts,” I joked. “Maybe,” he said. He took several shots, changed the film, and took one last picture.

We were done. But we resumed talking about books. And we continued to talk about books for the next 13 years, until his unexpected death. Bob would call when he came to New York and we’d meet for coffee just to catch up on each other’s reading. Bob was a more generous, less grumpy reader than I am, but I love more titles than I dislike. I am not a competitive reader, unlike many authors. With that in mind, Bob asked if I’d like to write one of the two introductions for his overview of queer American literature: I would write about the boys, Joan Nestle about the girls. Of course I said yes.

Dolores Klaich, lesbian feminist author and activist:

Bob Giard phoned me in September of 1986 to ask if I would put together for him a list of women writers who are lesbian. I happily agreed. When my list was done he said he would come by to pick it up, since we lived fairly near each other—he in Amagansett, me in East Hampton on the south shore of New York’s Long Island. When he arrived, by bicycle, I had been picturing him on his bike weaving his way around all the high-end East End traffic of Mercedes-Benzes, Hummers, and limos. Bob did not drive, an eccentricity of country living, but very much in keeping with his gentle way of being in the world.

While I made some tea, Bob began to unpack his photography equipment, and then I realized that he was not just after my list of women writers but was, it seemed, going to photograph me. Which, of course, happened, and I happily became the first woman who sat for his amazing labor of love project. When I made the list of women writers for Bob I knew the women would be in good hands. He, and his then-significant other, Jonathan Silin, were serious feminists—unlike a considerable complement of gay men back then who were not.

Some time later, after our photography session, when Bob sent me a poof of my photograph, I couldn’t have been more pleased, but it was odd that I was not wearing my glasses—since I had worn glasses (still do) since the age of 12. Did he see something in me that wasn’t there when I had my glasses on? ‘Tis a mystery.

I suppose full disclosure is needed here. Bob was a dear friend of mine for many years, I greatly admired his photography, and I was devastated by his too-early death. I couldn’t be more pleased that his splendid work is garnering wide attention in these unfinished days of gay and lesbian liberation. I hope that today there are any number of artists (of whatever genre) hard at work, as was Bob, documenting our lives. Maybe some of them are even traveling by bicycle.

Joan Nestle, writer, activist, and co-founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives:

How I wish I could visit the show of Bob’s work. I live in Melbourne, Australia now so 23,000 miles makes that impossible. But I have Bob’s image deep in my treasured memories. I remember him setting up that old box camera in the living room of my 92nd Street apartment which was also the home of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, and tall as it was, he was taller. While he set up, he spoke of his project to travel around America to do his portraits of lesbian and queer writers. He spoke in a gentle voice, as much to relax me as to share his passion for his work. We were trying to come up with an image that would locate me as a grassroots archivist as well as a writer. My memory—which may be faulty now that I am close to 80—is that together we decided on me holding the 1930s lesbian wall plaque that had hung on the wall of Ms. Mabel Hampton’s Bronx home for many years. I placed it on my shoulder as a symbol of the responsibility I felt for the work the Archives had undertaken in 1974. I was so honored to be the subject of Bob’s camera, and so moved by his dedication to his archival project which the AIDS epidemic had made so necessary. As Bob spoke I could see the depth of his quest deepening, he so wanted not to leave anyone out. He asked me for the names of other lesbian writers that he could contact. Never fancy, but totally dedicated to his project. Later, he gave a set of the lesbian writers’ portraits to the Lesbian Herstory Archives, a wonderful gift to us. Now as my generation grows old, as our time passes, these faces looking back at Bob, those bodies and rooms, are deep human history. My worry about the future of queer writing is my worry about Trump America. About the restricting of queer and feminist imaginative and politically engaged writings in a time of orchestrated hatreds.

Brian Freeman of Pomo Afro Homos, a queer African-American theater troupe from 1990 to 1995:

When Robert called me in Spring 1994, saying he was headed to the West Coast to photograph lesbian and gay writers, I was honored, thrilled to be invited to be in that company. It was clear he’d done his homework. He’d seen our group, knew the history, would also be shooting writer Jewelle Gomez on this trip, a friend and as good a name to drop as there is. The group was rehearsing for its biggest tour yet that summer—NY, London, Atlanta, and LA—and bracing for what looked to be a breakup of the original trio, a collective identity giving way to personal needs. Supreme’s fabulosity meets Destiny’s Child drama. Names called, wigs pulled. Just so hard to be the only Black-queer-anything in the universe. Robert encouraged me, later us, to just be present in our work space, the rehearsal room, but as writers. To let go, a bit, the performer’s need to present an engaging self, and let the contradictions of our lives and even this particularly uncertain moment show. No afrosheen, no makeup, nothing to sell, no need to hide. The chipped paint in the background reflecting the deferred maintenance of the building, a ballet studio rented from the archdiocese with a “no gay content” clause in their lease that no one would enforce, subletting to Pomo Afro Homos at a fabulous rate. The angularity of the arms an intentional nod to vogueing, to our fellow traveller Willie Ninja, and to the roots of performing Black queerness. The faces? Can’t speak for Djola Branner, or the late Eric Gupton, but I was thinking of all the brave things that a writer does, the joy of discovery in writing, and hoping my puffy eyes wouldn’t look so puffy, like my dad’s. The shoot happened in an hour, Robert felt strongly he got something. Robert went back to NY and published Particular Voices: Portraits of Gay and Lesbian Writers. The Pomos went on tour, and on to our own horizons.

James M. Saslow:

Bob’s portrait of me is my all-time favorite, not only because he caught an inner quality that has but few opportunities to reveal itself publicly, but also because his request to pose for him bestowed the gift of validation at a crucial moment. I doubt he thought his project’s purpose was to boost the egos of his sitters, a number of whom were successful and well-known authors— not a group known for self-deprecating modesty. But that was my reaction to his respectful letter, which explained that he was aiming to document the whole gamut of writers who were shaping a then-adolescent LGBT culture. Someone I don’t even know thinks little me is a literary lion? I still felt like a cub reporter.

True, I had a decade of part-time gay journalism under my belt, but I was only in my 30s, barely past graduate school, and my first book on queer art history was hot off the press and being coolly ignored by numerous scholarly publications. To be classed with Allen Ginsberg and Adrienne Rich was a validating reality-check: Yes, you are a creative thinker; yes, some people do take you seriously. For the first time it dawned on me: Maybe my passionate quest to unearth our long-buried queer visual history—hardly a selling point on the job market—wasn’t so quixotic after all. Bob’s invitation injected a welcome dose of self-respect and hope.

Bob liked to shoot his subjects informally, in their own familiar environment. Scouting my home for the best location, he asked about a pair of pointe shoes—souvenirs from my student days pursuing another passion, ballet—and a black alpaca cape, relic of hippie-era exotica. My New York apartment being typically cramped and cluttered, we hit on the idea of hanging the cape behind me to eliminate distracting detail and provide maximum contrast to the light glowing through the unseen window at left. The effect was so theatrical that I suggested including my old toe shoes. Bob at first resisted, wary of crossing the line between factual simplicity and the self-consciously “artsy.” But he went along once we both realized that the picture of a bearded ballerina, wistfully dreaming of a world where men could be as sensitive and graceful as only women were supposed to be, was worth a thousand words of what was then just becoming known as queer theory.