The story behind the keffiyeh, the traditional Palestinian scarf co-opted by Urban Outfitters.

Marginalized people have always fought for visibility, justice, and cultural pride through clothing. The Black Panthers wore berets that signified their power and unity, American college students affixed peace sign pins to communicate a shared goal of peace for the world, and Black Lives Matter activists take to the streets in hoodies to honor Trayvon Martin, whose unjust murder catalysed their movement. Palestinians fighting for the human rights of those in occupied territories, and in exile around the world, wear the symbolic fishnet-patterned keffiyeh (kufiya in Arabic) of their homeland as a display of solidarity.

The scarf native to Palestine has become a metaphor for the resilience of the nation’s people. Western news outlets’ coverage of Palestine is often limited to recounting the most recent act of egregious violence; just the word “Gaza” is enough to incite heightened debate. With the election to Congress of Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib, the United States’ political establishment is increasingly being pushed to speak about Palestinians and the injustices being perpetrated by Israel; the movement to #FreePalestine has 1.1 million Instagram posts and counting.

Hussein Musa, 25, co-founded the online clothing retailer PaliRoots with his sister and father. Musa, now based in San Diego, sells clothing and accessories that define the Palestinian experience, although he sees buying traffic from all over the world. One of PaliRoots’ most popular items is the traditional keffiyeh; as Musa says “The original keffiyeh is one of our bestsellers. We’re redesigning the website to highlight the keffiyeh, because it is a functioning part of the culture.”

Musa grew up away from his homeland as his father completed his medical degree in Saba and Belize, but he always felt a pull towards home. “Palestinians will tell you where they’re from even if they’ve never been, the occupation has done that to us,” he says. “We do not want to lose the land. Our grandparents instill that in us.”

Elias Jahshan is a Palestinian-Lebanese journalist based in London. He grew up in Australia, because in 1948, his then nine-year old father had to flee Palestine due to violence perpetrated by what are now referred to as Zionist groups. But, like Musa, he found the pull towards the home he had never lived in to be overwhelming. Jahshan calls this phenomenon “our inexplicable connection with home,” and says the keffiyeh “is a tribute to my Palestinian heritage, a symbol of solidarity, and a reminder to everyone who sees me wear it that we exist and that our culture and history is real.”

The scarf, in its authentic form, is made in al-Khalil (Hebron), Palestine, at the Hirbawi factory, the last standing keffiyeh textile factory in the world. Hirbawi was started in 1961 by Yasser Hirbawi, who has since passed and left the business to his son, but the proliferation of cheap alternatives to the traditional keffiyeh is threatening its existence. In 1993, the Oslo Accord created a free market in which China could produce inauthentic keffiyehs, among other products, and export them at a much lower price point than the Hirbawi family could. While that hurt the factory, it also caused Palestinians around the world to rally behind the father-and-son business. Musa sources his keffiyehs directly from this factory. “The sound of the machines,” he says reverently, recalling the beauty of the space, and going on to describe “the way the old man kissed his machines.”

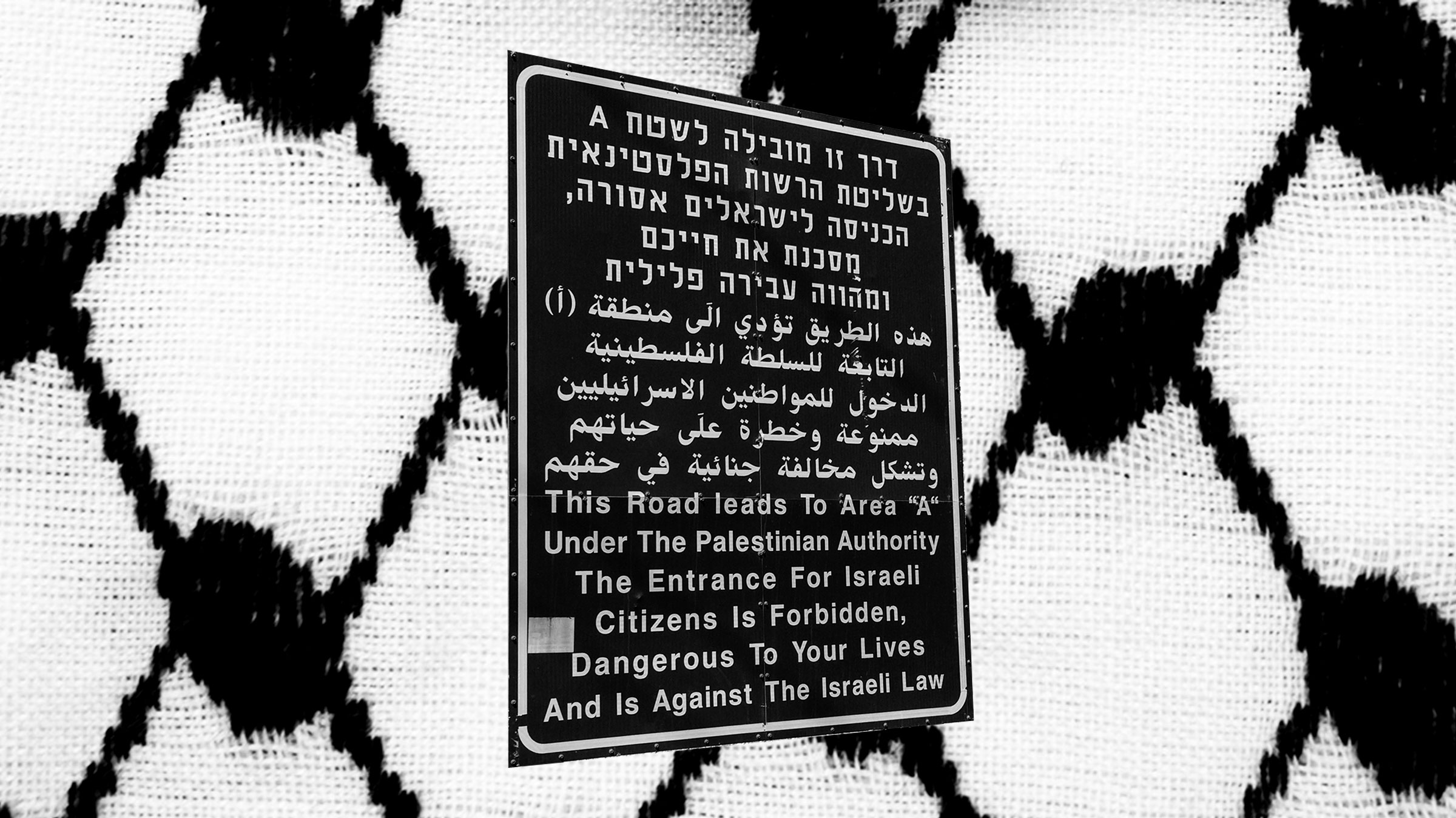

The 47”x47” keffiyeh has three key elements: the fishnet represents the livelihood of Palestinian fishermen on the Mediterranean sea, the lines cutting through the fishnet denote the integral trade routes that pass through Palestine, and the olive leaves symbolize the resilience and power of the Palestinian people. “We’re here to stay, we’re grounded and rooted,” Musa says of the olive leaves, their significance only heightened by the occupation and violence by the Israeli government. The wearing of the scarf is an extremely personal and sometimes political action. Musa even says, “If we don’t have it, we’ve lost a part of ourselves.”

But people from all around the world buy the keffiyeh from PaliRoots; many opt for the keffiyeh-printed long sleeve shirt, or the bandana. Designer Cecilie Jorgensen of Cecilie Copenhagen has an entire collection of keffiyeh-print dresses, skirts, and tops, calling the textile her “signature fabric.” And in the past 15 years, both Urban Outfitters and Topshop have faced international backlash for selling keffiyeh-print clothing. Visual displays of solidarity are one thing, but often these bigger brands disregard cultural symbols for profit that doesn’t benefit the Palestinian people.

Jahshan says, “This is not about who ‘owns’ or is ‘allowed’ to wear the keffiyeh. It is a reminder that some garments are inextricably linked to certain cultures and histories. To capitalize on them without the knowledge, sensitivity, or respect is just inappropriate and offensive.” Musa worries, too, about the way his people are represented across the world. He explains, “One of the signs as you enter West Bank says, ‘Warning! Danger. Your life is at risk,’ but really, if you stop at the first house to ask for directions, I’m sure they will welcome you in and feed you.”

The keffiyeh is a way for this misconception to change, and a reminder to the Western world that the existence of Palestinians is under threat. For a group of people that are misrepresented in media, attacked by the Israeli government, denied the decency of being recognized as a valid ethnic group, and forced into exile around the world, symbols of resistance can mark the difference between fighting alone and fighting together. Jahshan says, “I’ll continue wearing it to make Palestinians visible. If that makes people uncomfortable, then that’s their problem, not mine.”