At 84, Ghana's first professional female photographer finally gets international recognition at the Venice Biennale.

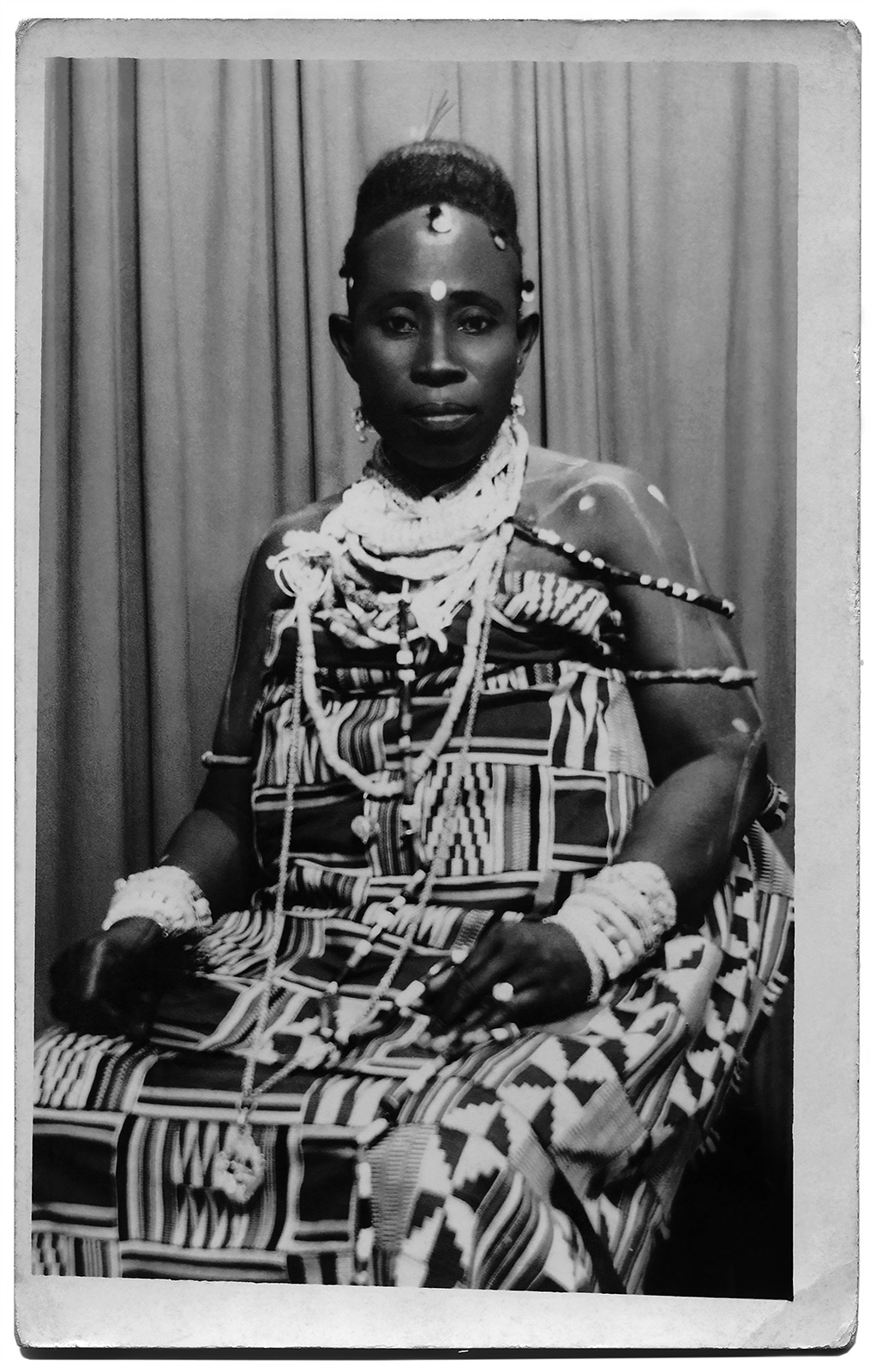

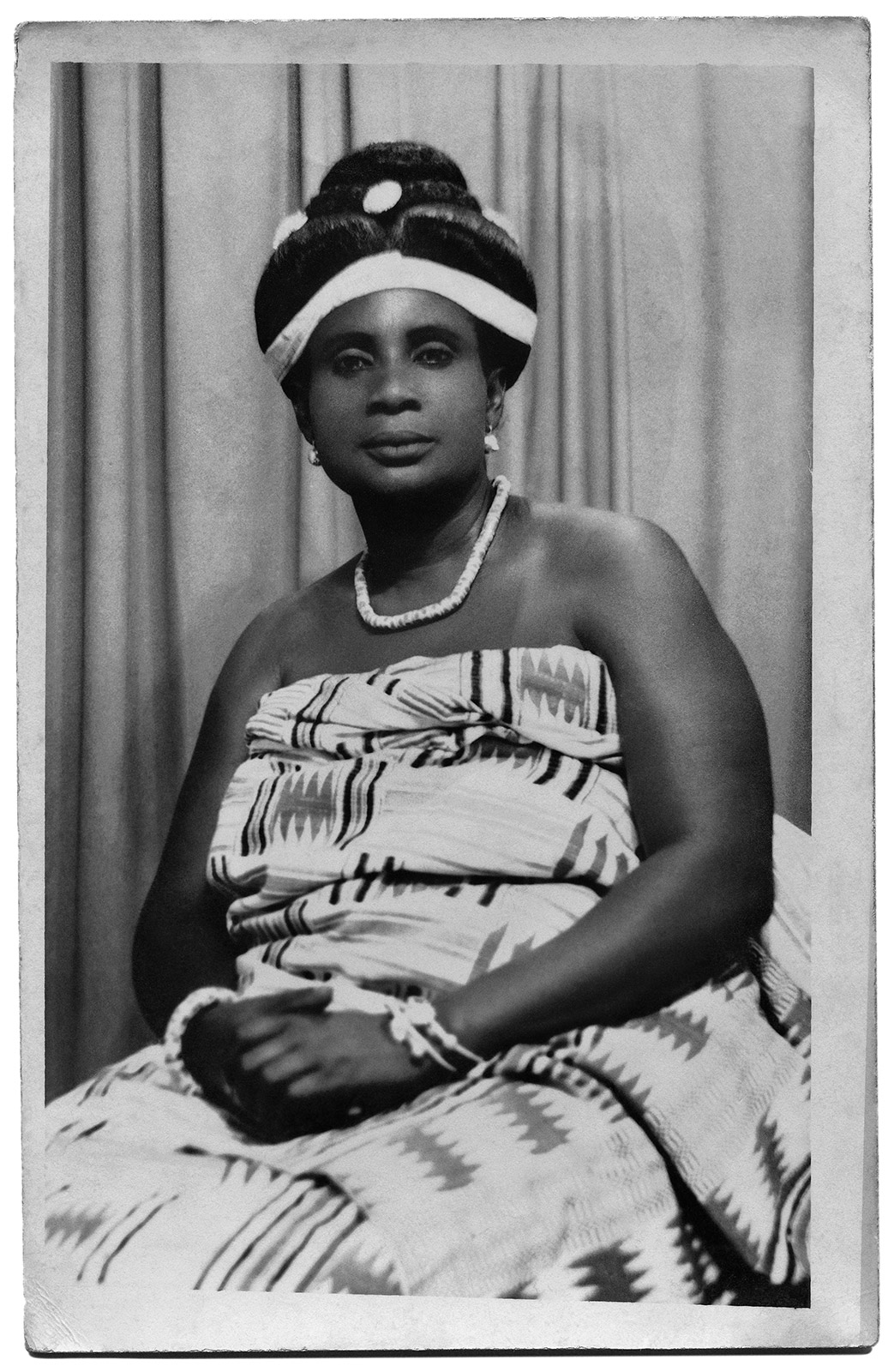

Each night, before she would go out to dinners, parties, and political events, Felicia Abban would take a photo of herself in her portrait studio. Her outfits ranged from a prim-and-proper shift dress accessorized with a string of pearls, to a traditional Ghanian headdress worn with hoop earrings. In doing so, Abban captured the look of Ghanian women in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Abban is widely known in Ghana as the first professional female photographer. She started training at age 14 in her father Joseph Emmanuel Ansah’s studio. In 1953 Abban moved to Accra, where she opened her own photography studio. She used her self-portraits as her calling card, and after Ghana gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1956, she became the official photographer of the African nation’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah. Abban documented the women of Accra in her portrait studio.

Abban is finally getting her due in the international art world some seven decades after she opened her studio in Accra. Nana Ofosuaa Oforiatta Ayim, the curator of Ghana Freedom, the exhibition in the country’s first pavilion at the Venice Biennale, selected Abban’s work to be part of the pioneering show. Oforiatta Ayim selected six artists from Ghana whose work represents three generations of Ghanian art: El Anatsui, Ibrahim Maham, Abban, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, John Akomfrah, and Selasi Awusi Sosu. Abban’s portraits and self-portraits depict a moment in Ghanaian history through her own female gaze, capturing their style and attitude. Document quizzed Oforiatta Ayim about why she included Abban in the David Adjaye-designed pavilion, why her photography was so groundbreaking, and Abban’s reaction when the 84-year-old learned she was going to be part of the Venice Biennale.

Ann Binlot—How did you discover Felicia Abban’s work?

Nana Ofosuaa Oforiatta Ayim—I’ve been working on digitizing and archiving Ghanaian photography for about 12 years now, starting with James Barnor’s work in 2007. [Abban] whe was one of several photographers I came across and began working with.

Ann—Why did you want to include her work in the pavilion?

Nana—The pavilion encapsulated pluralities and breadths of expression that stemmed from Ghana, it was important to me to have a voice that had witnessed independence, as well as a balance of genders. Even though West African photographers, such as Seydou Keita and Malick Sidibe, are well known, there hasn’t been much narrative on pioneering female photographers.

Ann—What does her portraiture say about Ghanaian women? Why was it so groundbreaking?

Nana—In her own words, she says she thought she could portray women better than the men around her. She was the only female photographer in a male-dominated field; the only official female photographer of our first president, Kwame Nkrumah. she was a celebrity of her time because of this. What is interesting is that so much of her focus was on female subjects, and on her self-portraits. What will be interesting to discover as I go deeper into the research is whether there is a difference and if so what in a female gaze.

Ann—When you met with her, what was she like? Did she have any anecdotes about photographing women in the ‘60s and ‘70s? Did she experience discrimination for it?

Nana—I have been in conversation with her for about three or four years now. She was still at her studio that she’s had since the ‘50s at the time. She has a lot of chutzpah still and I think like most women who succeed, just got on with it, despite the obstacles.

Ann—What was her reaction when you told her you were going to include her in the pavilion?

Nana—To be honest, she’s not that interested in the art world. She’s 84 years old and has, as she sees it, done her life’s work. I’ve become like family to her, and she was happy to indulge me in including her, but not too interested in becoming part of the art world discourse.

Ann—How does she want her legacy to be remembered?

Nana—I think she sees her job as done now. I’m trying to turn her studio into a museum at the moment and she’s happy with that idea. She spent a lot of her life training other female photographers, so I think this is a large part of her legacy. I’m working on a book on her work, and I think the narrative of her legacy will emerge from this.

Ann—Does she still take photos?

Nana—No, she’s retired now.