In his show ‘mEYEcelium’ the artist uses portraits of eyes to capture the lingering presence of his friends and loved ones.

There’s a famous Samuel Beckett short play, Not I, in which the entire action is distilled to a simple spluttering mouth. Seen on film, that mouth, close up, spilling a torrent of words, is mesmerizing. After a while it seems as if it must have jumped off the face to which it belonged and developed a life of its own. For a playwright who veered towards minimalism all his life, the 15-minute monologue is about as pure an expression of humanity as he would ever achieve.

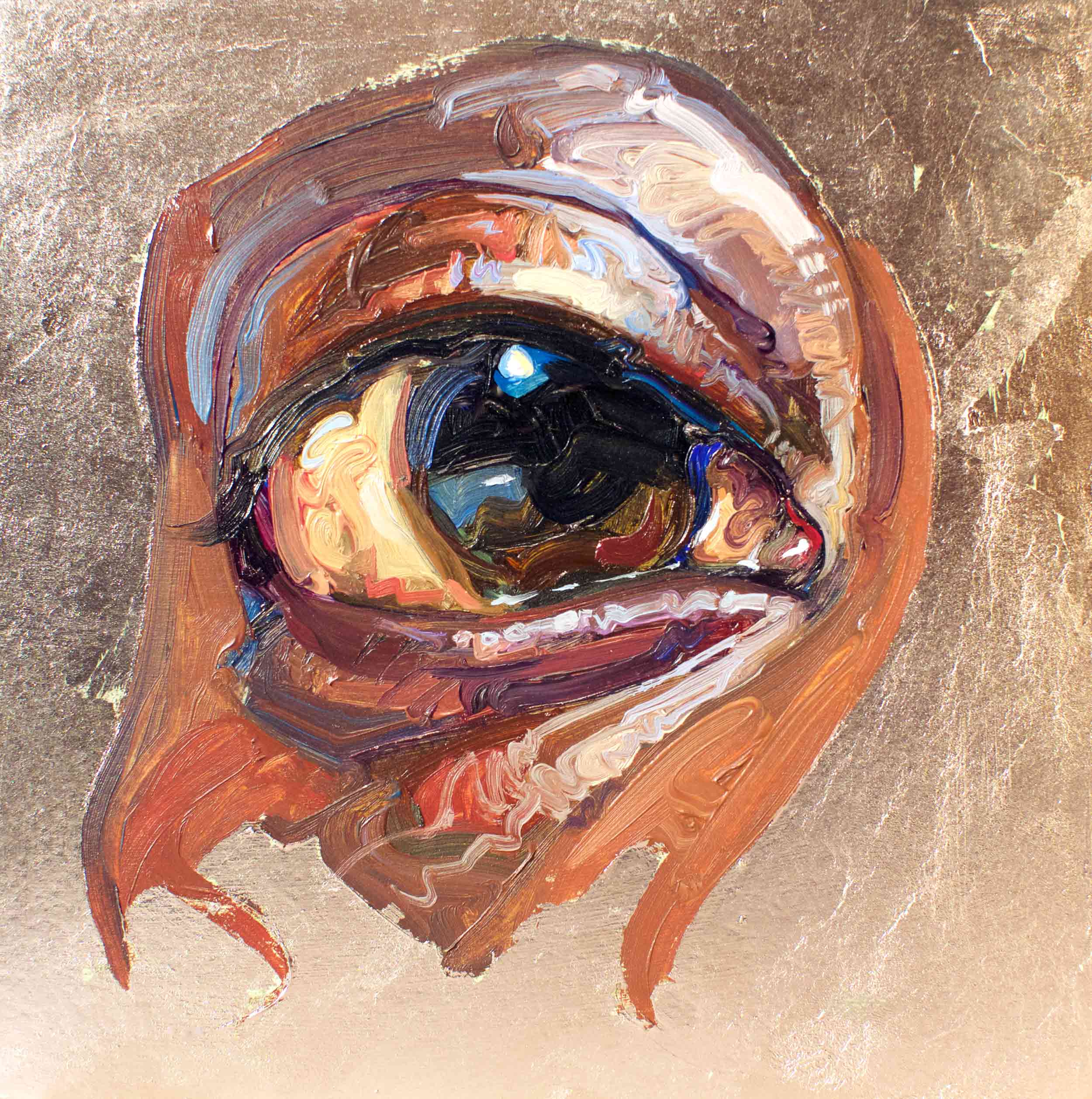

In his new show, mEYEcelium, at the gorgeous Palazzo Grimani Museum in Venice, the artist Sandro Kopp, has created something similar with the eye—abstracting it from the human face in order to amplify and deepen our relationship to it. Seen together, the eyes, 116 of them in total, become a silent, staring crowd. But in isolation each is as distinct and individual, and intimate, as a conversation. What have those eyes seen, what can they tell us? As the writer and curator Jasper Sharp puts it in an accompanying essay, “What we are and will become often begins with the eyes; it is here that love first takes hold, that envy seeps in, that we put together the pieces of the jigsaw that forms the world around us.”

Last week Kopp, who gravitates to oils, and tends—in the classical manner—to focus on portraiture of friends and family, was at his hotel room in Venice, taking receipt of a suit by Alexander McQueen. As we spoke via Skype, he showed off the fabric—embroidered with flowers and birds—and mused aloud on what nail varnish to wear for his opening. Possibly gold-leaf, he thought, to compliment his paintings in which the eyes frequently emerge through a gilded canvas, almost like a peephole.

Like his portraits of friends, such as the musician Michael Stipe and the actor and designer Waris Ahluwalia, Kopp plays with the tropes of religious iconography, surrounding them with precious metals and attending to their features with painstaking detail. Often, he’ll use palette scrapings to create a textured frame within the frame, echoes of the magnificent rococo frames of Renaissance art. There is nothing hurried in his work, which is about accumulation—of layers, of details—and of contemplation and conversation. It’s fitting that the show is paired with Domus Grimani, an exhibition of classical sculpture reassembled here, back in its original setting after four centuries, as well as a collection of work by the American abstract expressionist, Helen Frankenthaler.

The alchemy of two people in a room together is central to Kopp’s method—he resorts to photos only to complete a painting—and the eyes are no different. If you look carefully you see reflected in them the room in which they were painted, sometimes even the shadow of Kopp himself, held for eternity in the center of the pupil. “In a way, it’s about the moment of sitting together, looking into someone’s eyes,” says Kopp. “The byproduct of that is the painting, which is a trapped-in-amber piece of time.”

Kopp, who grew up in New Zealand and Germany and often takes his paints with him on his travels, has a lively curiosity that registers in the range of his subjects—musicians, artists, filmmakers, writers, friends from the lovely seaside town of Nairn, Scotland, where he lives with his partner Tilda Swinton. Late at night, when Kopp likes to work, he’ll hole himself up in a room, stream whatever jam is speaking to him (currently the Canadian cellist Zoë Keating and New Jersey’s Screaming Females) and paint into the early hours. “The truth is that with painting you need to do a lot of looking,” he says. “A lot of my studio time, if I finish working at two in the morning, I’ll usually spend another hour just looking at stuff, which is crucial because I get to know these new beings in the world, and I get to understand what they need to take them further.”

Here, Kopp talks about inspirations and muses, and how a painting can create presence through absence.

Aaron Hicklin—All your work is about family, friendships, love—these feel like the great themes of your paintings. But the eye, in particular, feel like the ultimate vehicle for capturing what’s essential about your sitters.

Sandro Kopp—It’s very much about human connection and about presence, and about a mediation of presence, which all my work is about. But also, it’s about absence, because the person has gone but their presence remains in the painting. It’s about creating something lasting out of this moment. And if you look at a portrait, you’re usually drawn to the eyes. That’s what captures your gaze. In a way, this series is like a greatest hits album. It’s like skipping all the other wonderful tracks on the albums and making a compilation of the greatest hits of the portraits of all the people I like.

Aaron—In many cases the eyes are embellished or encircled by gold leaf. What was the impetus for that?

Sandro—There’s something about this gilding process that immediately makes it feel historical. The moment that you put gold leaf on something you have this hard-wired associative historical line—you think, Egypt, Byzantine icons, baroque architecture. It conveys all these things much more than a color would. Every one of the sitters is someone I admire, and I think that in turn is where the gold leafing comes in because it does feels as if there’s an elevation of that person’s presence in that.

Aaron—Were you ever tempted to continue and fill in the rest of the face?

Sandro—I thought about that a lot, but although they are small paintings, they are over life-size for eyes, and a full portrait would be quite huge, really monumental. So, it’s also like those fragments of sculptures or paintings that have survived, with just a fragment of the body, but which convey the presence of the whole thing in the part.

Aaron—You’ve done a notable series of portraits from Skype sessions, but you don’t love painting from photographs. What’s the alchemy of the subject sitting in real time that makes it work for you?

Sandro—It’s spending time together, and that’s why the Skype stuff also works—it doesn’t have to be in the same room, it’s even quite exciting for the subject to be around the other side of the planet. Of course, I’d prefer to sit with someone in a room for the sake of being able to really see, but the conversation or even silence—the company of it—makes a vast difference to the end product. It’s the thing that I need in order to do what I do.

Aaron—Who are the artists that serve to inspire and guide you?

Sandro—Lucien Freud is someone I admire greatly, and there’s the Swiss painter, Ferdinand Hodler, who was a contemporary of [Gustav] Klimt, and I literally stole stuff from him: the particular type of pigment that he uses to create dark shadows, and which gives this wonderful fleshiness. Technically he’s someone I very much lean on. In terms of those working these days, Jenny Saville is amazing, Marlene McCarthy, and the Nigerian painter Njideka Akunyili Crosby, who is in the pavilion [at the Venice Biennale], and is fabulous.

Aaron—Do you recall a moment that defined your calling as an artist?

Sandro—I remember the first time I did life drawing. I was so focused I stopped breathing—I forgot to breathe. It was just this real sense of, Ok, this is what I’m supposed to be doing. My interest in portraiture initially came out of wanting to do better faces on my nudes. Then the faces just became more interesting for me. At some point in life I’d still love to do a substantial body of nudes but it’s so difficult to find a unique angle on nudes. I feel I need to find the chink in the armor of what everyone else has done, especially working from life, because there are only so many ways that somebody can hold a pose for three hours and they’ve all been done, like a million times. I need to come up with a personal way of approaching nudes, and then I’ll do that. I usually have a series of parallel fields that I’m plowing, if you will, and then at a certain point a certain field comes up and is ready for harvest, but at the moment the eye harvest is in full bloom.

“mEYEcelium” runs at the Palazzo Grimani Museum in Venice through early September.