The photographer’s experiments in shadow and light reform gender and racial boundaries in a portfolio for Document S/S 2019.

Ming Smith is a pioneer. She was not only the first female member of Kamoinge, the African-American photography collective established in 1963, but also the first black woman, in the late 1970s, to have photographs acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Born in Detroit and raised in Columbus, Ohio, Smith moved to New York in 1973 after graduating from Howard University and took up modeling to support herself. Working alongside Grace Jones, Bethann Hardison, and Sherry Bronfman, Smith was among that seminal generation of black women to achieve success in the fashion and beauty industries. It was during this time that she began experimenting behind the camera as well.

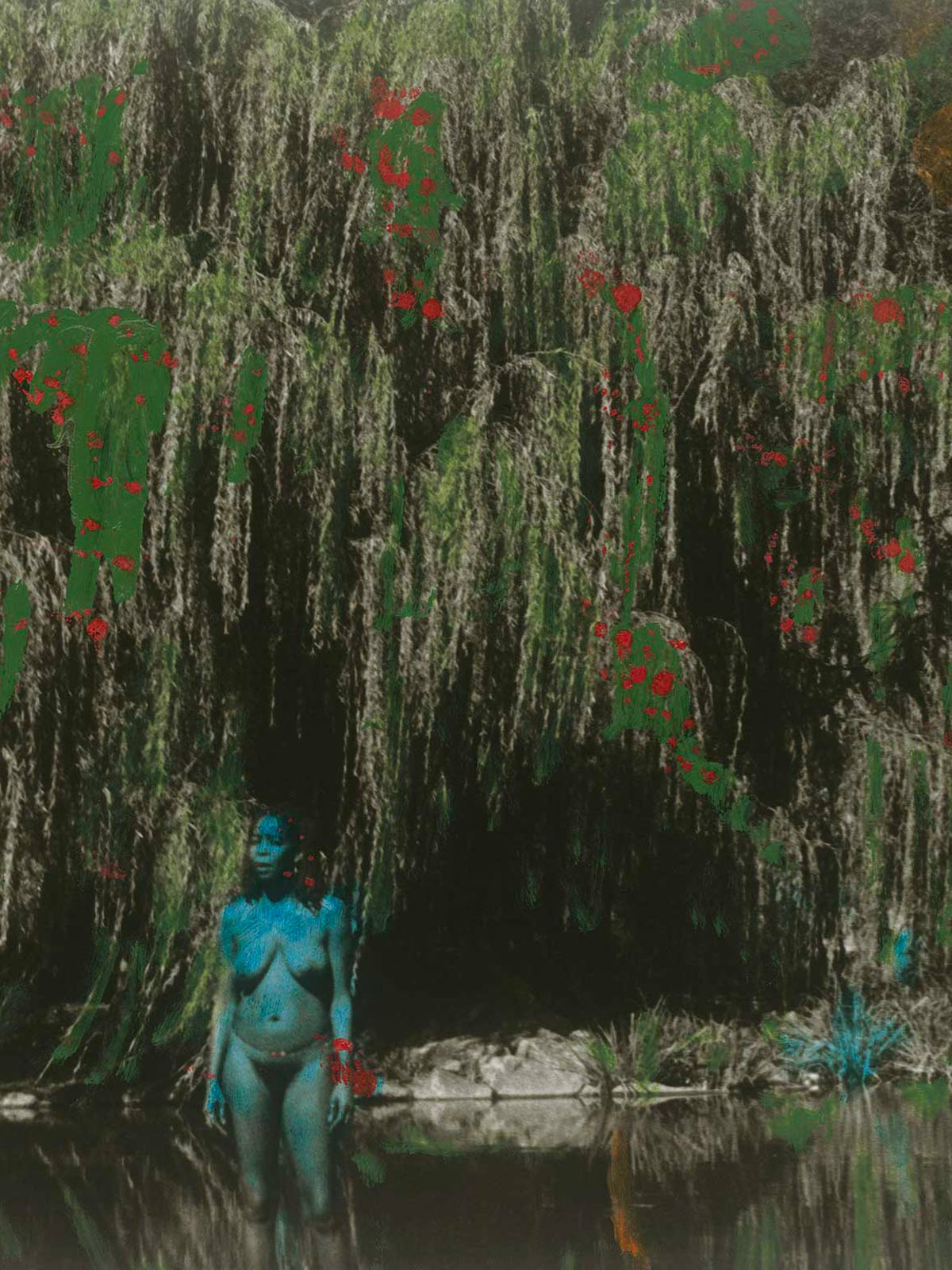

Over the past several decades, Smith has photographed numerous subjects, from abstract images of architecture and portraits of black cultural figures to street scenes in Harlem and Pittsburgh. A through line of the work has not only been black people in all their complexities and multiplicities (one of the core principles of the Kamoinge group), but also an interest in formal experimentation—whether it’s blur effects and double exposures, incorporating the sprocket holes of her negatives, or painting directly on her prints. As a result, her subjects are often caught between visibility and invisibility: faces or bodies are turned away, or blurred or shrouded in shadow effects and paint—perhaps a metaphor for the struggle for African-American visibility in the art world, as well as in broader cultural production in the United States. Indeed, she titled one of her series Invisible Man, borrowing the name of the 1952 novel by Ralph Ellison.

Smith’s photographic experimentations draw upon the legacy of surrealist practices from the 1920s and ’30s, which similarly used double exposure and other techniques to question the medium’s relationship to reality. Since the late 1970s, Smith has explored another hallmark of surrealism: the nude. While many of the predominantly male artists of that period focused on the female body, Smith initially turned her lens on a male subject. These early photographs display her ability to harness shadow and darker tones, much like the work of Roy DeCarava, an early member of Kamoinge, who similarly photographed black figures using available light. The sense of spirituality found in Smith’s photographs is equally evident in her personality. Perhaps this is what has allowed her to carve her own unique path, breaking through gender and racial barriers along the way.