Following her artist portfolio in Document S/S 2019, Ming Smith speaks on representation, improvisation, and photography as a form of survival.

See Ming Smith’s artist portfolio for Document S/S 2019 here.

Photographer Ming Smith has been infiltrating historically exclusive institutions for over four decades. Originally from Detroit, Smith moved to New York City in the early 1970s, and found herself smack in the middle of the Black Power Movement. In swift succession, Smith became the only woman in the iconic collective of Harlem artists Kamoinge, and the first African-American woman to have photographs acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. But Smith has always been insistent on one thing: she’s just on her journey.

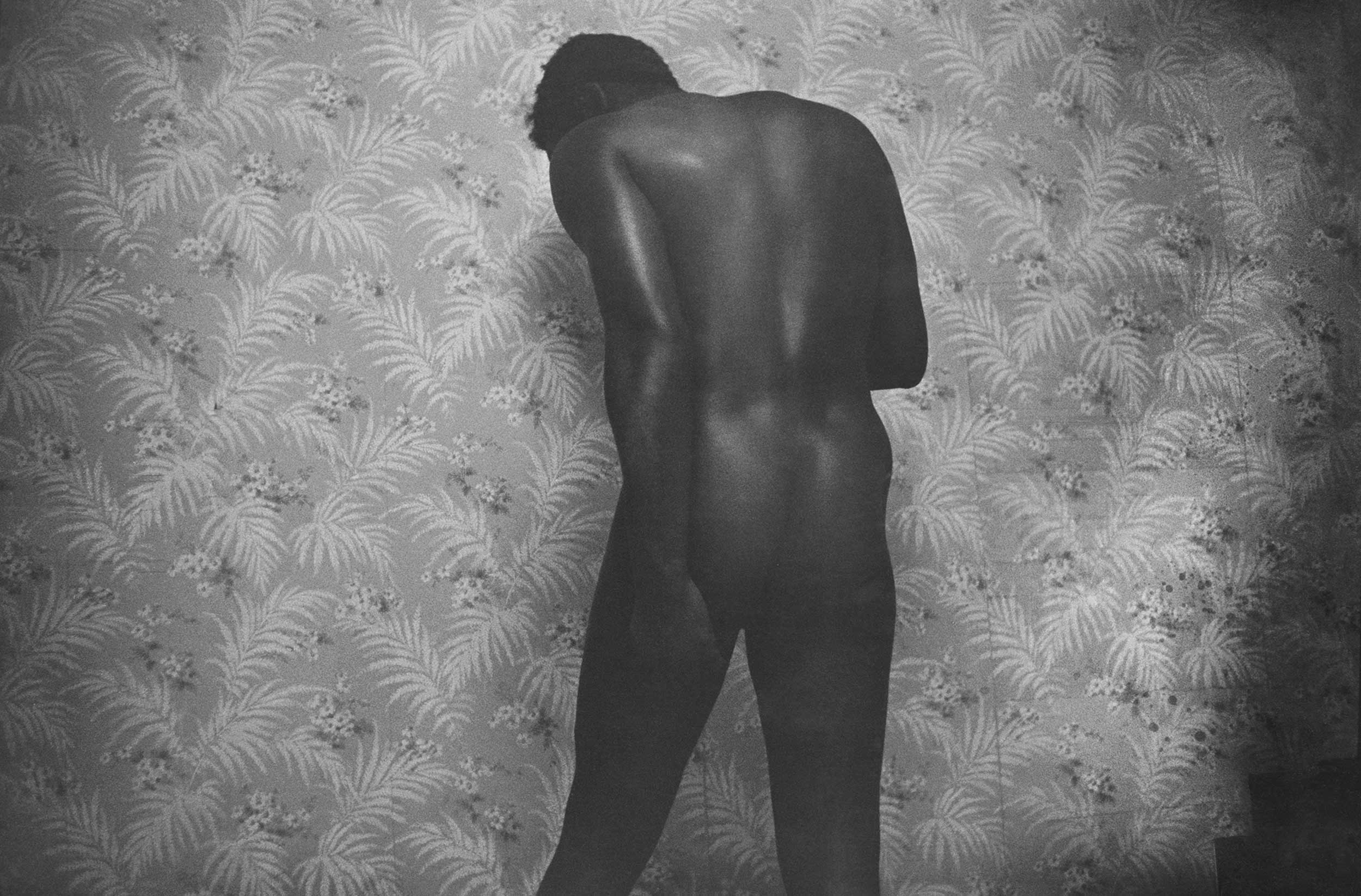

Smith’s photographs haven taken her across the globe, photographing a diversity of subjects and experimenting with a range of forms. She’s photographed children in Dakar with the same grace and respect she showed when shooting the world’s most respected dancers, musicians, and writers of the 1970s. Her work is ethereal and inherently spiritual. As with all great photographers, her images are not static, and affect us differently each time we interact with one.

In recent years, Smith’s work has rightfully gained a renewed relevancy. As talks of proper representation continue to spin, Smith serves as a necessary reminder that change can be as simple as following one’s own path. Document caught up with Smith at the opening of Women’s Work, a group featuring her and four other female artists from across the globe at Pen + Brush, to discuss photography as a form of survival, representation, and improvisation.

David Brake—I took a writing workshop with Zadie Smith and she referenced that in order to write like a writer, you had to learn to read like a writer. How do you see, as a photographer? When you walk outside is there something tangible, something that you notice, something that you look for?

Ming Smith—Well, I’m really old school. I look at the light–that’s the first thing. Everything is about light. If you look at yourself in the mirror at sunset, or you look at yourself in the mirror in the morning, depending on how the sun is hitting the mirror and your face, you could look good, or you could look bad, or you could just look different. So one of the first things I would tell someone who was aspiring to be a photographer is [to look at] the light.

David—In a lot of your work I notice experiments in form, whether they be double exposures or different kinds of overlays or compositions. How do these formal experiments change or alter the subjects?

Ming—I actually see those images when I’m photographing—what’s on film is what I usually see. They weren’t manipulated images. I photographed them as I saw them. But I photograph the way a person paints. Some people say, “I paint with light.” In the beginning they all [said], “Well she paints with light, her photographs look like paintings.” Through aesthetics, seeing, and doing it over and over again, trying to catch that image at that moment, all of those—that’s the art form.

David—I just watched Swizz Beats’ new video series where you talk to Arthur Jafa, and you said something really interesting. You said, “Photography was a way to survive.” I was wondering if you could talk a bit more about that.

Ming—We were alone. I was always a loner, and photography was my best friend. It’s like someone who goes to yoga, or to a dance class, or sports, where they work out things. Photography was that for me. I could be in my own world, I could create, I could be one with myself. Say something was happening and I was upset, I could always go out and be in the world, and commune with nature—because I do trees, I do birds, I do people. When I was in California I saw a lot of trees and foliage, and landscapes. So it’s a way of being with one’s self. It can be very meditative, and I always feel better afterwards. It’s the act of doing it. Later, after you see your images, then you choose, but you’re in your world, and you’re creating.

“Photographs are empowering, but bottom line, it’s been a spiritual journey. It was something that was leading me.”

David—Do you consider yourself an activist?

Ming—I would say yes. I was always very anti-establishment when I was growing up. I loved Angela Davis and the Black Panthers; those were people I looked up to. I was basically a shy and quiet person and I could never be on a platform to talk and preach. But photography—bottom line, photography has been a spiritual journey. It’s something that I always did. I remember someone saying, “Either you built up or tore down the system.” And photography was my way of confronting the injustices and the images of black folks. Let’s take one particular image—they said there were no fathers in the homes, but when I saw the world, [the] people in Harlem or wherever, there were a lot of fathers, and they were being fatherly, and they were being lovely. It was an inaccurate stereotype that they perpetuated in the newspapers and media.

David—Since you started have you noticed a change in terms of representation?

Ming—It still goes on. The will still goes on. White supremacy, injustices, are still going on, but there also are [those] who are actively trying to go against that. As of recently, I think there’s been more talks. We’re going to all need to work for change, and go forward, and I think we’ll be able to get the job done. And I’m just one little drop who’s trying to do my part. I chose to work against the system. I try to show truth and love in my photographs. Photographs are empowering, but bottom line, it’s been a spiritual journey. It was something that was leading me. It wasn’t intellectual, I was just on my journey.

David—Reading people that have written about your photography, they always turn to the spirituality, and it’s just undeniable in your work–this ethereal kind of presence. When you go out to take photographs, is that something that you are actively looking for? Is it something you stumble across and you find?

Ming—Oh no, it’s all discovery, it’s all improvisation. It’s like when jazz musicians solo. They improvise, and photography is definitely that, for me.

David—My favorite photograph of yours is of Sun Ra, where he’s glistening. It’s lovely to see mediums blend together, and how you work with so many people of all different types of mediums. The Swizz Beats video is a perfect example of that. How has music affected your work?

Ming—I’ve always been fascinated by artists in general. Quite honestly, most of the photographs of other artists—I wasn’t there to photograph them, but they were in my life, they came to me, or it was just my journey, and I photographed it… Many times as an artist—with all of the suffering and poverty and climate change, and every horrible thing that’s happening to humanity in the world—I think, “Is it even worth making a difference? Why am I doing this?” Especially during moments when there was no support at all. But it was about documenting the culture. Even though a lot of these folks—say, Imamu Baraka, who started the Black Arts [Movement] right along with the Black Power Movement—weren’t really mainstream, the black [community] had this huge, beautiful culture of value. For me, I can say, “At least I have these photographs.”