The artist pounds, massages, and wrinkles images of Playboy models into radical feminist art in Document S/S 2019.

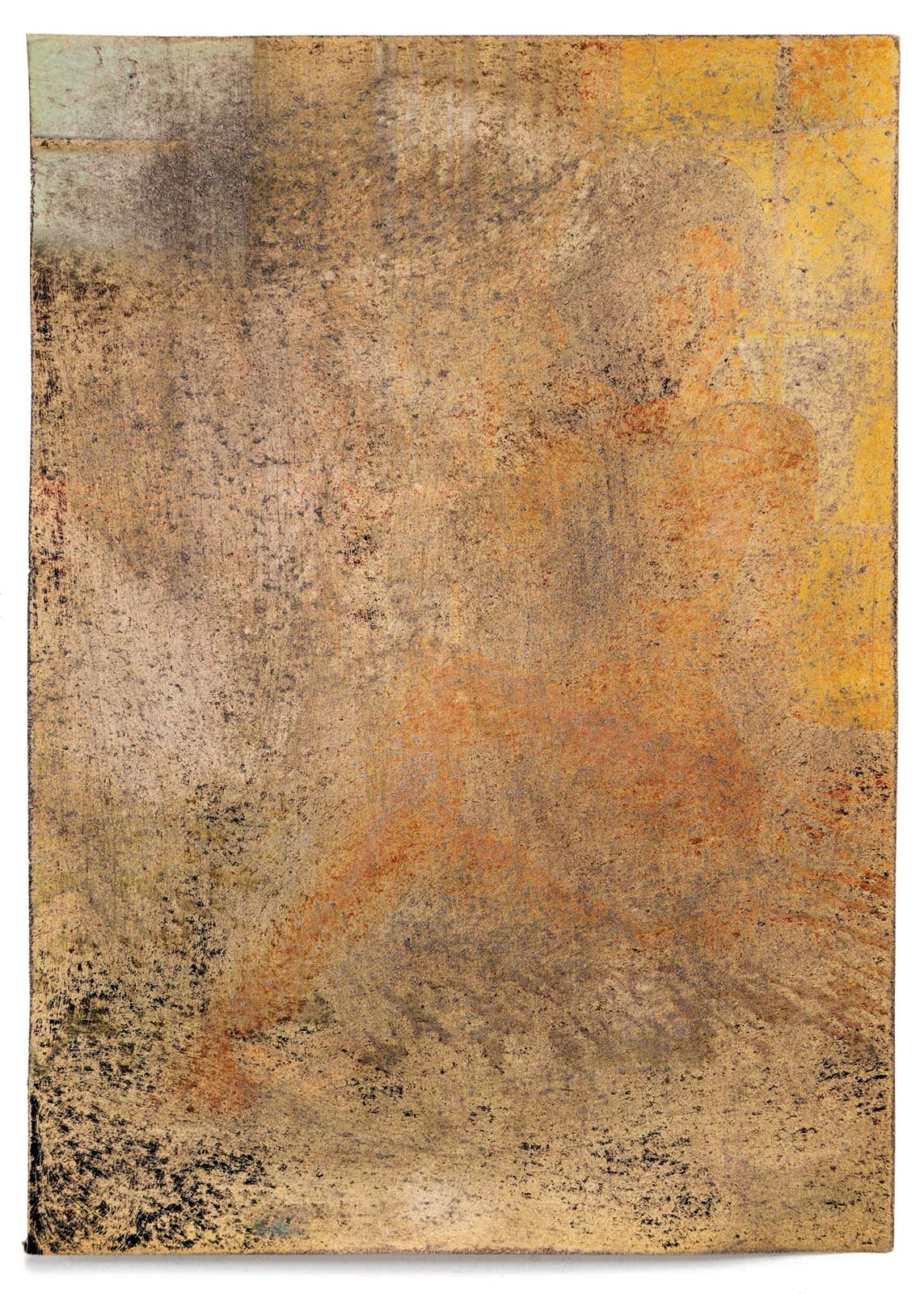

As part of her artistic process, Carmen Winant regularly browses garage and estate sales, collecting a wide array of photographic imagery that she accumulates in the studio and integrates into her work. At one such sale in her Columbus, Ohio, neighborhood, she sifted through the possessions of an elderly man, finding among them a collection of Playboy magazines from several decades past. Pulling each centerfold from the binding, she worked them over one by one with her hands, massaging, pounding, and wrinkling them, rubbing away the surface until the facial expressions and curves of the depicted figures became almost imperceptible. Her method is one of both destruction and tenderness: She erases the body even as she caresses it. As the artist describes, the black ink is the first to go, revealing the paper beneath, which, in some cases, “turns the positive image into a negative.”

Erotic images at once invite the viewer in and keep us at a remove; viewers can behold the body, but cannot enter or share its space. Though bodily pose and proximity may suggest a physical closeness, the fact remains that this is a two-dimensional image, comprised of ink on a magazine page. Yet at the same time, our perception of these works is simultaneously visual and haptic. This makes intuitive sense, as we don’t just look at photographs, we spend time with them in other ways. Winant emphasizes the physicality of these photographic objects through her own handling of them.

After training as a photographer as an undergraduate student, Winant now works primarily with appropriated photographic images, constructing collages and ambitious installations that investigate representations of women: Who gets pictured? How are they pictured? Where are such images found? Why? She has often returned to images made and initially disseminated in the 1970s—the period in which the magazine photos in this portfolio were printed. It was when the women’s liberation movement was in full swing, and women were voicing their empowerment around their own bodies. Photographs produced for Playboy magazine may seem counter to some of these efforts, though here, too, as throughout her work, Winant calls attention to the work of women, by highlighting its visibility but also shining a light on its invisibility.

Though the imagery in these pictures have been rendered almost abstract—ghostly vestiges of what were once glossy figurative depictions—their original state as photographs from an earlier generation remains essential. The ability of photographs to touch us, by evoking a memory or standing in for a significant event or individual through the traces of what was, has by now been abundantly narrated and theorized. Here, Winant has touched them back.