Writer Bob Morris reflects on the alternative weekly golden era with Hilton Als, Lynn Yaeger, Michael Musto, and Vince Aletti.

This article appears in Document No. 14, available for pre-order online now.

Once upon a time in New York City, before Craigslist and Grindr, readers would wait at newspaper stands on Wednesdays for The Village Voice to arrive. They relied on the fierce alternative weekly’s listings for apartment shares and quirky personals ads. Suburban and city kids used the tabloid paper with the blue logo for music reviews and underground concert listings, while serious theater, film, and book lovers depended on Voice critics to read between the lines and apply both cynicism and semiotic theory. And if you wanted a takedown of the powerful, including landlords, city officials, and Donald Trump, you could trust the Voice to do so with precision and panache.

Co-founded in 1955 by Norman Mailer—who quit writing his abrasive column because an editor made a proofreading error, mistaking “nuisance” for “nuance”—the Voice was one of the nation’s first alternative weeklies and was considered the most successful for decades. It created the Obie Awards for off-Broadway theater, covered marginalized cultures, and nabbed interviews with Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and Che Guevara. Its publishers, including Clay Felker, Rupert Murdoch, and Carter Burden, had clout, and its readers had attitude.

Pulitzer Prize winners Hilton Als and Colson Whitehead wrote for the Voice, as did Pulitzer nominee Nat Hentoff. Peter Schjeldahl, the New Yorker art critic, and Guy Trebay, the heady New York Times style reporter, gained momentum there, as did Times art critic Roberta Smith and Jerry Saltz, the jester critic of New York magazine (and another Pulitzer winner). Legendary director Jonas Mekas was its first film critic. Editor Bill Bastone left the paper after starting the muckraking website Smoking Gun. Political author Michael Tomasky went on to write for New York, The Daily Beast, and The Guardian. Legends like feminist Susan Brownmiller, literary darling Vivian Gornick, hip-hop arbiter Touré, and cartoonists Jules Feiffer and Lynda Barry walked their wits weekly in the paper, which for years was thick with ads. And for those who needed a massage or escort, the back pages offered that, too.

When the Voice shut down for good, in 2018, it wasn’t much of a surprise—even in New York, the biggest media town in America. In 1996, it became free in order to increase circulation, which many supporters felt lowered its intellectual clout. Then it moved to online only in 2017. The internet was, of course, the cause.

The response was profound, with countless media eulogies decrying the loss, from the socialist-leaning The Nation to Fortune. “The Village Voice, a New York Icon, Closes,” read the Times headline. Mailer, in a 2007 interview with the Times Literary Supplement, had called the paper “an important organ” and “perfect” for this country. “We really did something for America,” he said. It was the last interview he gave before he died.

How did The Village Voice achieve, and then maintain, such relevance? What kind of place cultivates such a strong and diverse stable of talent? Here, some legendary voices from the Voice reflect on its decades of prominence.

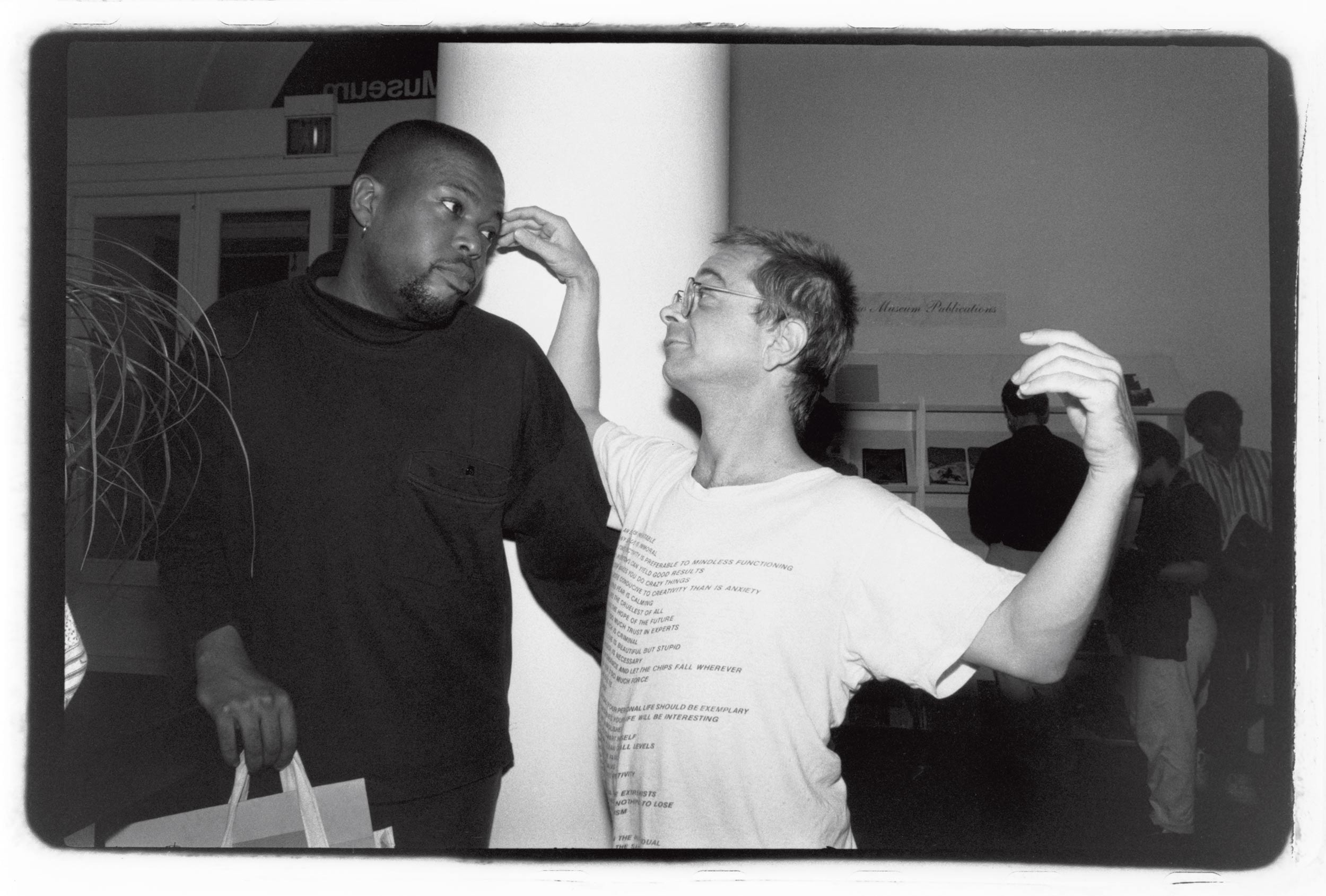

Hilton Als, Staffer and writer, 1984 to 1992

I was the art department assistant. I never assumed that I was going to be writing. That’s not what they hired me for, but it was such a non-hierarchical place that no one ever said no. To this day, I have enormous trouble observing the boundaries in publications because my real training was at the Voice, which was way more of a collective. It became this kind of family. Ellen Willis was an editor who was one of the smartest people I’ve ever known. You could just go to her and say, “I don’t really understand intellectually how to work out this problem,” and she would help you. There was never a door that was closed. There was never anyone saying, “I’m more important than you.”

I was really drawn to the people of color who worked there. It’s probably the most diverse place I’ve ever worked, and it was way ahead of the curve in that way. Everybody was a New Yorker and everybody was of a different color.

Lynn Yaeger, Fashion writer and editor, 1978 to 2008

It had an incredible freedom in terms of what you could write, and you were encouraged to be yourself. It was very much a home of eccentric writers and personal journalism.

I worked in the classified department and became head of the union with Jeff Weinstein, and he pushed the whole idea of domestic partnerships for insurance coverage. After I was there for a while, they hired a fashion editor, and I asked if I could write something for her about shopping, and she said okay. And she printed it, and then I wrote something else about packing for Europe, and she printed it. Then, and this is a true story, Helen Gurley Brown read my article, and she bought it for Cosmopolitan magazine. And she called up David Schneiderman, who was the editor at the time, and said, “You have such great writers there—like Lynn Yaeger,” and he said, “Lynn Yaeger’s in the classified department.” But that was my big break.

Later I became the fashion editor and I didn’t know anything. I thought we could take clothes from a store, shoot them, and return them. But I had an intern who told me, “No, you’re supposed to shoot the clothes from the next season—there’s a showroom and you borrow those clothes.” We didn’t have any fashion advertising, so I could be just as mean and reckless and ruthless as I wanted to be. I remember one time Harold Koda, the curator of the Met Costume Institute, called me up and said, “I have to meet you because I cannot believe the nerve that you have to write these things about my exhibitions.” He had done an Armani show at the Guggenheim and I said it looked like the sales rack at Loehmann’s.

“The Voice was ahead of its time trying to iron out issues of identity. I see people having these debates now, and I roll my eyes because we talked about the exact same things 20 years ago—gender and identity.”

James Ledbetter, Media columnist, 1990 to 1998

If you opened yourself up to The Village Voice, the chance was very good that you might get trashed. It wasn’t an outlet that was necessarily going to take P.R. pitches at face value. Part of the role of a publication like that was to poke through the hype.

There were office debates, at times enhanced by the diversity of the staff. In some ways, the Voice was ahead of its time trying to iron out issues of identity. I see people having these debates now, and I roll my eyes because we talked about the exact same things 20 years ago—gender and identity.

I liked the vibe of the office. There were old and young folks, people of different races and sexual orientations, and everyone shared a kind of left politics. People would wear strange clothes and do weird things. There was music playing, and there were people who had weird magazines that they’d show you. Some people would have Japanese pop culture fanzines. Some would have obscure Marxist-influenced slacker zines. Some would have feminist studies journals. It was crazy eclectic—a fun, carnival-like atmosphere. And you could learn a lot just by walking around and looking at what other people were working on.

Jeff Weinstein, Senior editor, 1979 to 1995

There was a lot of dirt, a lot of books, lots of rats and mice, and it was a very lively office scene at Broadway and 13th Street—a kind of warehouse-sized open space near the Strand, and the last office before Cooper Square. There was a lot of sleeping around. At holiday parties there was stuff going on in the back rooms, and I remember at one we had a gay-porn room and a straight-porn room with old videotapes on loop. That was pretty amazing. I still wonder how that happened. I never saw anybody have sex at the office, but I know they did.

The big division was always between the front of the book and the back. The front of the book was for politics and run by all white men. Nat Hentoff, Jack Newfield, Tom Robbins, Joe Conason, and some others went after people that other papers wouldn’t touch. Like Wayne Barrett going after Donald Trump in a deep investigative way in the late ’70s, long before Spy started going after him. I think he called Trump “a user of users.”

But the arts got a lot of readers, too, and they were very important to the paper ever since The Village Voice started. The politics and the arts overlapped when it came to race, gender, and gay stuff, and that crossover is ultimately what the Voice did that nobody else did. We were trying to make sure that we were on the edge all the time.

Robert Christgau, Senior editor and music critic, 1974 to 2006 and 2016 to 2017

What I believe happened to improve the quality of the Voice is that Clay Felker bought it in the 1970s with the idea of turning it into another version of his New York magazine, but for a slightly more downtown crowd. He didn’t last long. But what made a tremendous difference is that he put money into the fucking paper. A lot of the guys who owned alternative papers were really nuts about not spending money. Felker, on the other hand, was an uptown spendthrift. He instituted a weekly drinks-included editors’ lunch, to which selected writers were also invited. It was the only time in my life I ever drank more than a beer at lunch. I even got sloshed once or twice. I was an actual music editor who cared about music criticism. I knew there was a bunch of good writers out there. So when I had the money, I hired them. We didn’t pay a lot but we paid better than most. Money’s very important in journalism, if you haven’t noticed, based on what’s out there today. And the fact of the matter was that the paper was making money hand over fist. In the late ’70s and the 1980s, in particular under Murdoch, it did extremely well. Then the shit began to hit the fan in the ’90s, and it was killed by the internet, like all journalism.

Vince Aletti, Art editor and critic, 1985 to 2005

The Voice had much more engaged photojournalism—being on the scene, being very present. Fred McDarrah was an incredible early influence on the paper as a photographer and editor. He knew that he was the eye of The Village Voice, and covered anything from a Beat Generation cocktail party and the Stonewall uprising to the art scene.

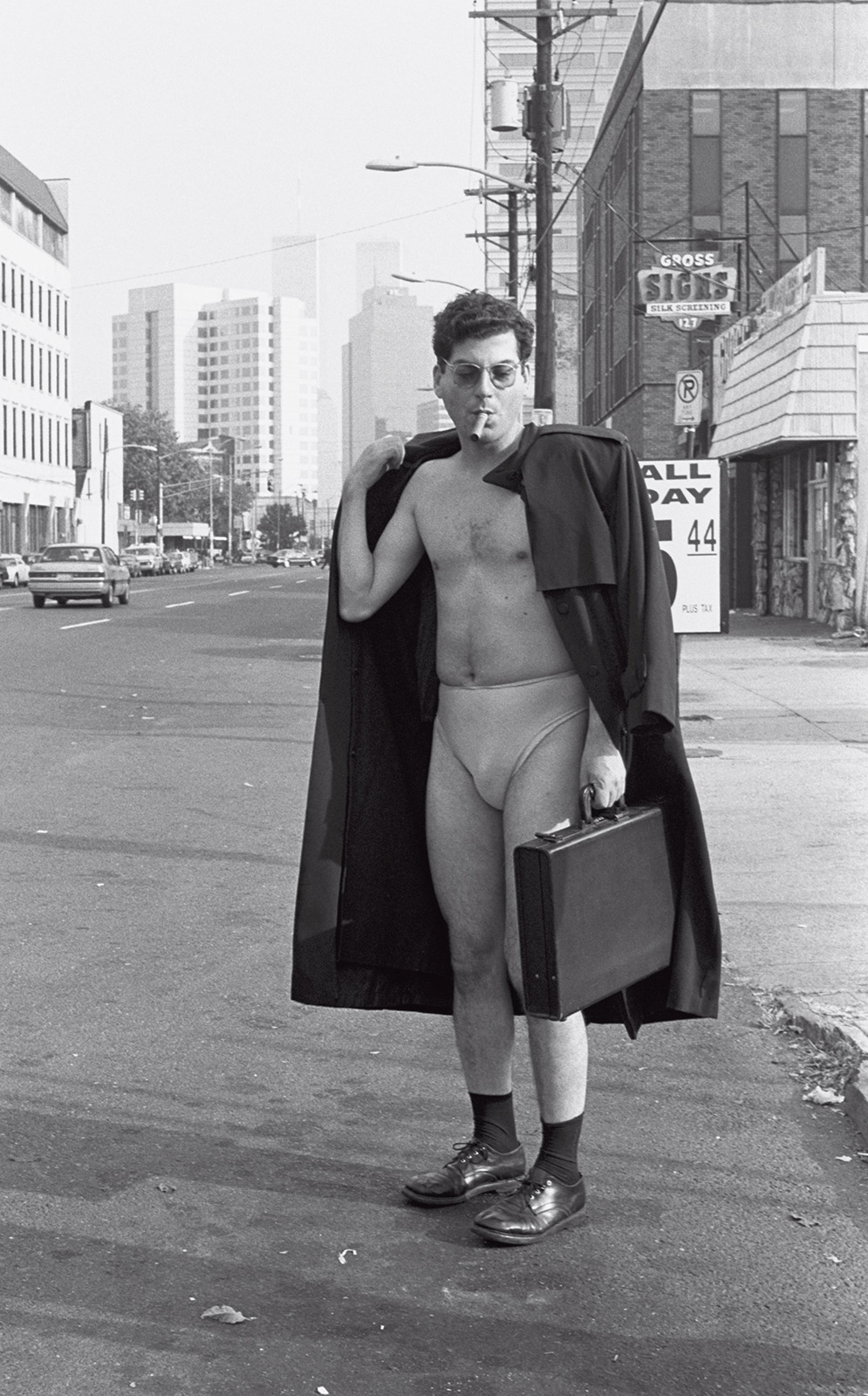

Sylvia Plachy, I think, was the first great extension of Fred’s way of looking. She would print panoramas. She would use cameras that were imperfect so she would have an impressionistic view. And then there was Amy Arbus. Her contributions in fashion and all her work on the street was so influential beyond the Voice in terms of how people saw fashion as not something italicized or in quotes but as something people wore all the time. She really saw the life of the street and gave it a frame.

“It was this countercultural paper in the back, but the front was this hard-hitting thing that every F.B.I. agent in the city took really seriously.”

Amy Taubin, Film critic and columnist, 1987 to 2001

The Voice, like any newspaper, relied on movie advertising, so there was always coverage of big Hollywood movies. They could not ignore them, but the critics Andrew Sarris and J. Hoberman found ways to take them on from a different position. I had a column called “Art and Industry” about independent film, in the 1990s. I was writing about people like Jim Jarmusch and Spike Lee, but they would never be on the cover. So the film section was a place where you saw a very traditional hierarchy of culture. And then we would write our 10-best-films-of-the-year lists, and it wasn’t full of Hollywood movies, and everyone would say, “What the fuck are those films?”

Writing about film can bring up power issues, of course. I remember talking to the director Neil Jordan about The Crying Game and he was very open with me. We discussed the revelation at the end of the movie, which had to do with gender, and specifically genitalia. I submitted the interview and a Voice fact checker called Miramax, who made it clear that I was revealing the film’s ending in the interview. Harvey Weinstein went ballistic and called the editor and film editor—and they said the decision about what to print was up to me. I said I wanted to go with revealing the ending. When he heard that, Harvey went even more insane. Neil called me and told me if I don’t get the Voice to kill the story that Harvey would shelve the film. I really liked the film and Neil and I capitulated. I never wanted to be the cause of this film not showing in the U.S.

Another time, I wrote an essay about Fight Club in which I interviewed director David Fincher. I really liked his work and I thought Fight Club was a great film, but I would never be able to buy into the ending—the fact that Brad Pitt’s character was actually a projection of the imagination of the Ed Norton character. The problem was that Rupert Murdoch hated the film because they blow up a building at the end. And, like Harvey, he was threatening not to release it. So Fincher couldn’t take any criticism of the film at all because he was looking for all the help he could get, whether from the Voice or any other publication. Three years later, he was still so upset by my criticism that it ended up on the introductory commentary track of the DVD.

Michael Musto, Columnist and reporter, 1984 to 2017

I was an openly gay writer who went to extremes. Some of the intellectual and political snobs there looked down on me, but the paper promoted me like crazy because my column was popular. So I felt it was my responsibility to be opinionated and funny, but also target the big guys and ruffle feathers. I got a telegram from Whoopi Goldberg saying “get a life.” I thought Jay McInerney was going to get violent in my face once. David Geffen was mad at me because I wrote something about how he was promoting Guns N’ Roses even though Axl Rose had said stupid stuff about gays and black people. Spike Lee froze me out once. I’d always just think, “Well, at least they’re reading me.” You can’t go out there hoping to be loved by everybody because then you’re not doing your job.

But things have changed because the homophobes are in the minority now. There are out LGBTQ celebrities. It’s a whole different landscape, so there’s less to be angry about in the entertainment world. John Waters once told me that you can’t carry that level of rage with you your whole life. Eventually you mellow, the world around you changes, and a little bit of that is your own doing.

Michael Tomasky, Columnist, 1990 to 1995

The difference between the Voice and other papers was that those were huge newspapers with dozens of people covering New York City. We had a few people—I mean, literally. The fact that the Voice could get scoops and beat The New York Times was just astonishing. It was this countercultural paper in the back, but the front was this incredibly hard-hitting thing that every F.B.I. agent in the city took really seriously. And it was a writer’s paper through and through, when newspapers weren’t like that.

It had a long heyday. I don’t know that what constitutes really good journalism has changed that much. I just think that the sort of organic community that produced the Voice got scattered to the winds, you know, by gentrification and too many high-priced chain boutiques in SoHo.

There were disagreements and frustrating times, but everybody loved the place. That’s what animated the reunion party that we had a couple of years ago. That and the death of Nat Hentoff and then Wayne Barrett right around the time of Trump’s inauguration, when Wayne was still working on Trump stories, probably even on his way to the hospital. We thought maybe 100 people would show up for the reunion. But 350 people came. It was a very emotional night.