On the occasion of Chloe Wise’s portrait exhibition ‘Not That We Don’t’ at Almine Rech London, Document reached out to her subjects to gain their perspective.

Posing for a portrait can be an awkward task; whether it’s with classmates, colleagues, friends, your family—or even complete strangers. Last fall, as New York-based artist Chloe Wise embarked on a new series of paintings, she started thinking about the cultural mores that surround group settings. “I started with the idea of doing group portraits with the intention of looking at the way that the dynamics play out within parameters, whether it’s a room, or the edges of the canvas, or in the photograph, how social interactions and hierarchies play out—the codes and rules that we all agree to in order to exist harmoniously as a group,” said Wise. Wise found herself keenly observing the facial expressions of those around her with a painter’s eye, so she invited individuals from her own network of friends—some were complete strangers to each other—to sit for the series, which began with a photo shoot. The results of Wise’s sociological investigation through portraiture are currently on view in an exhibition titled Not That We Don’t at Almine Rech London until May 18.

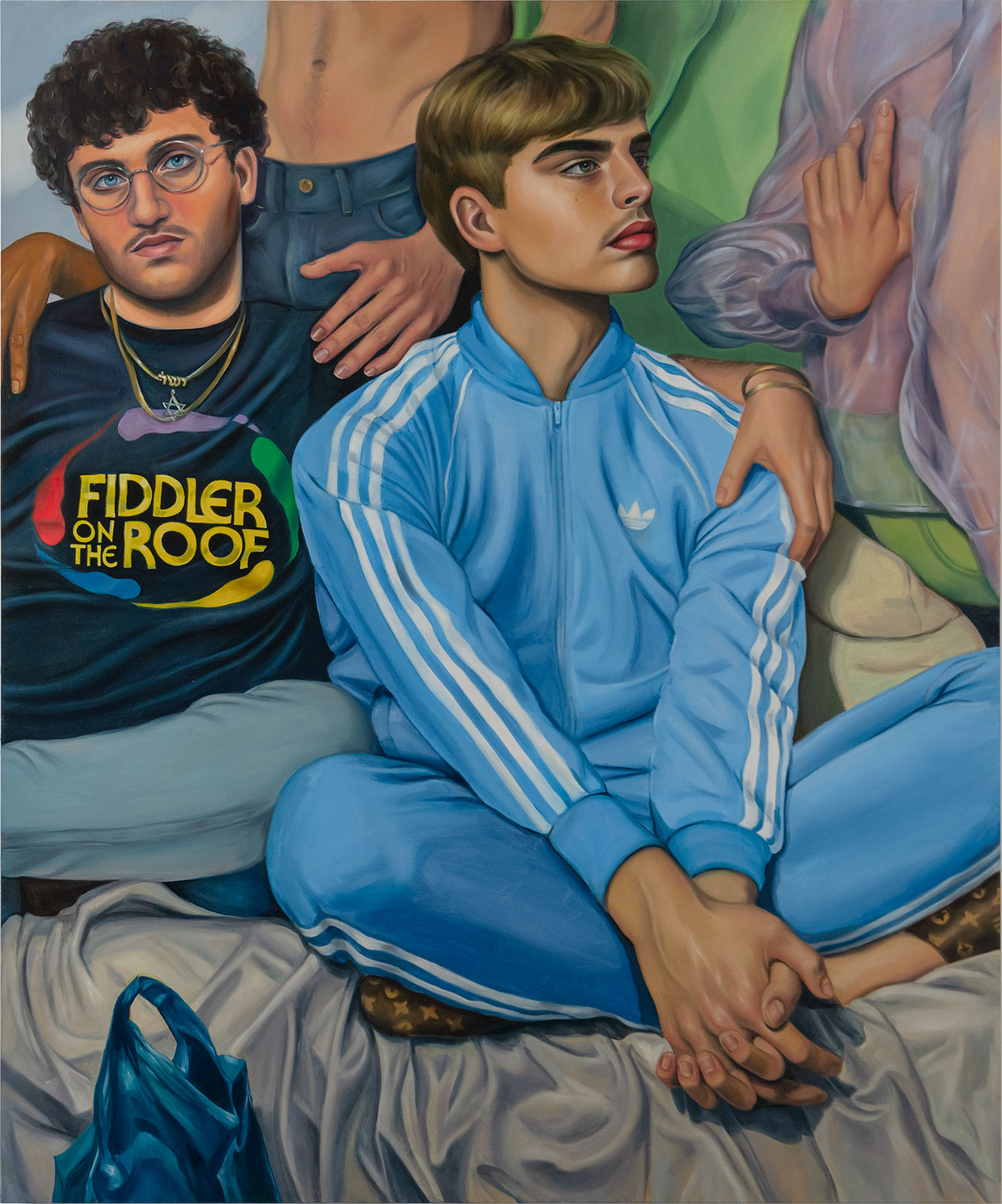

Wise gathered everyone in her studio over two days, and orchestrated their positions to induce a subversive, underlying interaction, causing the viewer to see the level of comfort and trust in their faces. She also filmed a quirky two-channel video that opens the exhibition. “I’m always investigating their features as we hang out,” she said. “The way that we decode facial expressions is integral to guaranteeing we exist harmoniously within society. How we avoid being othered by our group, or how we avoid chaos is reliant on our ability, in part, to decipher subtleties.” The placement of her subjects’ hands become their own characters in the paintings. “There is a subtle feeling that exists just below the surface,” she said. “These fake smiles, a hand on someone’s shoulder or knee. These gestures could be indicative of patience or feeling settled, or out of being forced to sit there for a long time. It could be oppressive or supportive until you realize there’s a double meaning and two ways of reading it, which is why the title is a double negative.” Informed by French philosopher Roland Barthes’s Mythologies, which features an analysis of detergent advertisements in 1950s France, Wise places “sanitizers” like Kleenex, Purell hand sanitizer, and Reynolds Wrap in the hands of her subjects. Sculptures that look like benches come with a paper towel dispenser or a tissue box built in. “You can draw parallels with how we’re supposed to trust in structures of society,” she said. “Like, Don’t worry, the government will save you from the dirtiness and impurity of bad, abject things.”

Although the artist’s point of view is often recorded in art history, seldom has the perspective of the artist’s subjects been documented; what was the woman in Leonardo da Vinci’s famed Mona Lisa thinking as the Renaissance painter sat behind the canvas? Who was the woman in Johannes Vermeer’s Girl With a Pearl Earring? Alberto Giacometti biographer James Lord outlined his tedious experience as the Swiss artist’s last subject, which was immortalized in the recent film Final Portrait. Document wanted to go behind the scenes of Not That We Don’t, so we reached out to four of Wise’s subjects to learn about their experiences sitting for the artist. Here are their responses:

Adam Eli, 28, Community organizer and writer

Document—How did you meet Chloe?

Adam—Chloe and I were introduced through Kay Kasparhauser in 2013. She showed me a photo of her newest piece, a Jewish star made of bacon called The Star Of Larry David. The rest is herstory.

Document—Describe your relationship with her.

Adam—Unadulterated support and joy. In our seven years of friendship we have thrown not one, but two Hanukkah parties, a seder, travelled internationally, and never had a single fight. Last year I was in Paris for work on my birthday and I didn’t really know anyone there. Chloe informed me that she was going to throw me a birthday party and told the time and name of a tiny restaurant in Le Marais. I showed up and found 20 Parisian strangers and a gaggle of the most beautiful European art gays I had ever seen. They all hugged me, wished me a “Joyeux anniversaire!”, sang to me, paid for my dinner, and then took me to a fashion party. That’s what being best friends with Chloe Wise is like.

Document—How did you end up sitting for her?

Adam—She asked me and I told her to name the time and place. She has done so much for me, I felt like it was the least I could do. Up until recently she primarily painted woman so my facial hair and I were thrilled to be included her growing body of work.

Document—Describe your experience sitting for her.

Adam—Sitting for Which lake do I prefer, 2018 felt like sitting for a family portrait gone eerily wrong. At first it was just fun, being surrounded by people I know and love in Chloe’s studio, a space I know well. It felt a bit like attending the shiva of someone you don’t really know. You are with a bunch of near-strangers in an unfamiliar living room, munching on culturally informed snacks and sort of nodding at each other. You are all there for the same reason, but do you say hello or just focus on your rugelach and Dixie Cup of orange juice? Then I started to notice a few odd details—why was this empty plastic bodega bag posed next to me as if it were a human subject? Where did all of this coconut oil come from and why did people keep rubbing it on me? A topless man was instructed to put both his hands on my shoulders. I tried to make eye contact with the other subjects, hoping one of them would acknowledge how bizarre this all was, but I had no such luck. So I sat there tersely, my face inches from my new friend’s happy trail and dissociated a little.

Document—What do you think her painting is all about? What does it say about the era in which we live?

Adam—I think this painting is about the humor and humanity we create to avoid the chaos we actually feel when interacting with people we don’t know and don’t really want to be around. The result is a well moisturized commentary on the extent to which we’ll “act normal” and pretend like “everything is cool” when in actuality we are deeply troubled by what is happening around us.

Vere Van Gool, 30, Associate director at IdeasCity at the New Museum, and an independent curator and writer

Document—How did you meet Chloe?

Vere—We met through mutual friends in New York.

Document—Describe your relationship with her.

Vere—Chloe is one of my dearest friends and neighbour in the East Village.

Document—How did you end up sitting for Chloe?

Vere—She organized a session at her studio where she invited friends and peers to come together as she was exploring this idea of the group portrait.

Document—Describe your experience sitting for her. Why did you choose the clothes you wore? Did she pose or style you? What was it like?

Vere—It was a brilliant and exciting experience. Upon Chloe’s direction, we all experimented with our postures, behavior, and facial expressions. What was striking though, is how natural the process was. Chloe wanted us all to be ourselves, and yet simultaneously the setting she provided allowed for us to follow her curatorial mission; asking questions about group dynamics, communion, the self, performed inclusivity, and this ultimate question about belonging. Given Chloe’s interest in contemporaneity and the politics of everyday commercialization, I was wearing bold colors, contrasting one another in both material, texture, and style.

Document—What was it like when you first saw yourself in the painting?

Vere—When I saw all the works together, in sequence with her videos and participatory exhibition design, it felt very powerful. And admittedly a little weird, as this painting will live on to have its own life, away from me, and while I will change and obviously age, the image will stay the same. Professionally, it’s been incredibly insightful, as most of my work organizing public programs and exhibitions has a time limit; shows that close and talks that end. This painting will live on.

Document—What do you think her painting is all about? What does it say about the era in which we live?

Vere—Chloe’s paintings are a brilliant and illuminating snippet of her world, and using the medium of painting and video, she is transforming selected fragments and frames into an investigation of our contemporary society. Through addressing the everyday commercialization of our society, as well as the awkwardness of human behavior and group dynamics, she is able to capture the zeitgeist of our generation—one marked by consumption, globalization, and digital identity. What I love most, though, is how in each of the works she renders visible a question about belonging, and the struggle we all face to fit in, or not.

Ian Bradley, 33, Fashion editor/stylist

Document—How did you meet Chloe?

Ian—Through mutuals, while bopping around NYC. We really bonded on a bizarre “influencer” trip.

Document—Describe your relationship with her.

Ian—Two fun-loving Sagittari who enjoy socializing, pretty boys, and dancing—we also love one-on-one heart-to-hearts.

Document—How did you end up sitting for her?

Ian—She asked and I was there! Chloe had mentioned a couple months before that she wanted to focus on her friends for her next series, was hoping I made that list.

Document—What was it like when you first saw yourself in the painting?

Ian—Crazy! I’ve been illustrated by friends before, but never painted. I thought I knew her talent, didn’t expect it to be so spot on. I have a hard time making eye contact with the painting, to be honest.

Document—How does being in a painting compare to seeing your likeness on Instagram and social media?

Ian—Somehow, it looks more like me than any iPhone picture.

Document—What do you think her painting is all about? What does it say about the era in which we live?

Ian—What I love about Chloe’s work is that it’s reminiscent of the dreaminess of classical oil paintings, but has a contemporary sense of humor and irony. Also, I love the range of diversity of characters she chooses to capture, I’m honored to be among them.

Carly Mark, 30, Artist and fashion designer

Document—How did you meet Chloe?

Carly—A mutual friend.

Document—Describe your relationship with her.

Carly—Very close. We travel together, speak everyday, our animals are best friends.

Document—How did you end up sitting for her?

Carly—She asked nicely.

Document—Describe your experience sitting for her. Why did you choose the clothes you wore? Did she pose or style you? What was it like?

Carly—Chloe styled me, I appreciate the irony. I know what she’s looking for in terms of posing.

Document—What was it like when you first saw yourself in the painting?

Carly—It felt like me.

Document—What do you think her painting is all about? What does it say about the era in which we live?

Carly—Chloe is great with people, she knows how to connect. These paintings are just as much about her connection with the subject as they are about the subject’s connection with any other viewer. You feel like you’re part of something, even if you can’t exactly put your finger on what that something is. She titles things in a very similar fashion. You’re about to get it, but then it slips through your fingers. She has you coming back for more.