The photographer’s latest series ‘I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating’ captures a glimpse of people in their own homes.

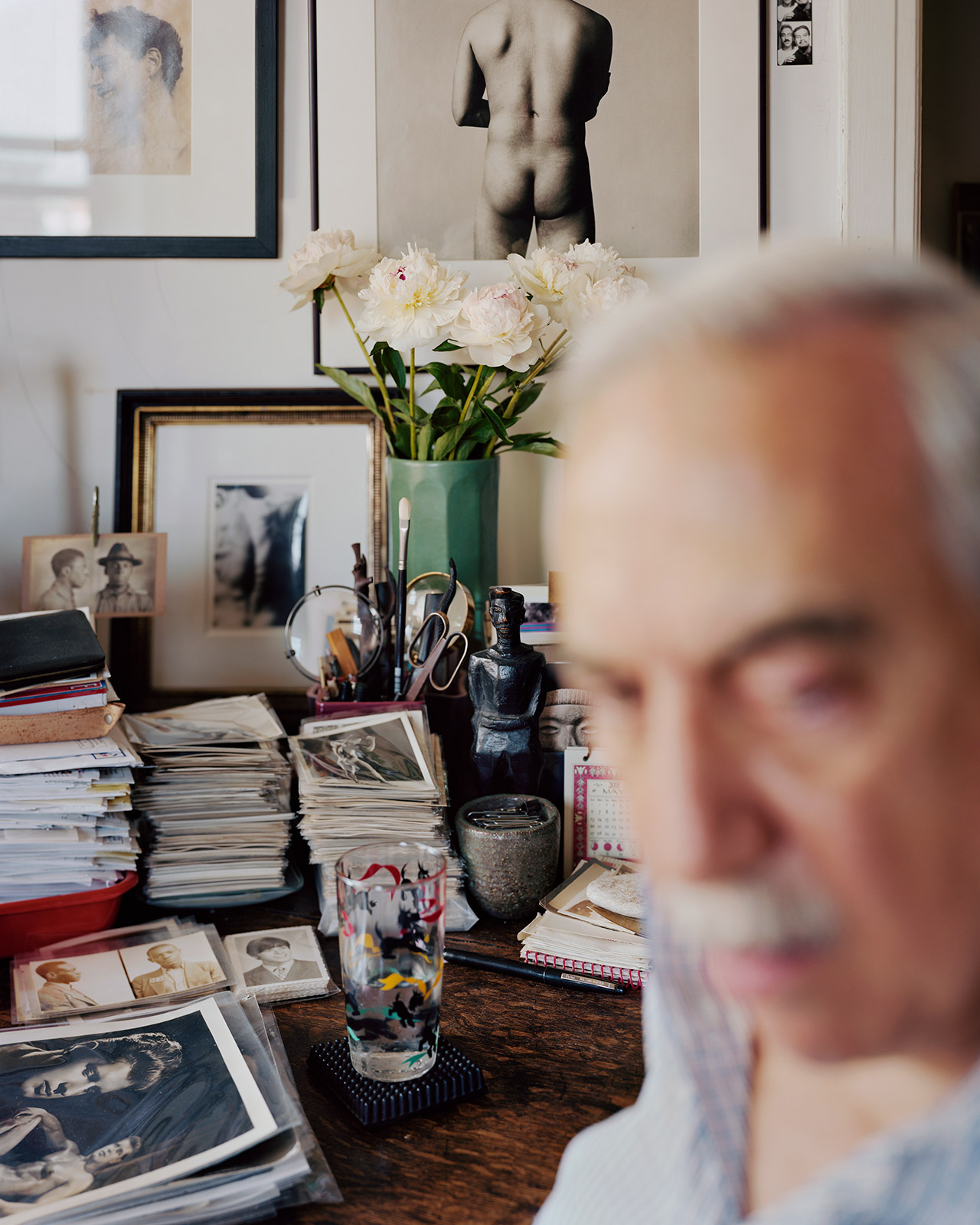

Alec Soth needed a break. For most of his career, he photographed those on the fringes of society in specific areas—the neglected denizens of America’s “third coast” in “Sleeping by the Mississippi,” or the love and romance that people seek through hotels in his series “Niagara.” Laura and Kate Mulleavy, the fashion designer sisters behind Rodarte, even tapped the photographer to collaborate with them on their 2011 book Rodarte, Catherine Opie, Alec Soth. He decided to take a pause to reconnect with nature, forgoing the constant travel and human interaction that had become a regular part of his life. The move would prove fruitful, leading Soth to embark on his latest project, titled after a line in a Wallace Stevens poem. I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating, for which he traveled throughout the United States, the United Kingdom, and Europe, is a series of portraits of people inside their homes, the place where they usually are most comfortable. The results were compiled into his newest book of the same name, and four exhibitions: In Minneapolis at Weinstein Hammons Gallery from March 15 to May 4, Berlin from March 16 to April 18 at LOOCK Galerie, in New York at Sean Kelly from March 21 to April 27, and in San Francisco at Fraenkel Gallery from March 23 to May 11. Document caught up with Soth to discuss his hiatus, the genesis of I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating, and the power of meditation.

Above The Fold

The Form Challenged: Backstage New York Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Realized Attraction: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Nick Hornby: Grand Narratives and Little Anecdotes

Wearing Wanderlust: Waris Ahluwalia x The Kooples

Ann Binlot—So you took a long hiatus from photography, right?

Alec Soth—I took a hiatus from a certain kind of photography. During that year I took pictures, but I wasn’t traveling and I wasn’t doing jobs. Probably most importantly, I wasn’t photographing people. But I was making pictures of light and nature and stuff like that.

Ann—Why did you feel that you needed a sabbatical?

Alec—I didn’t think of it as a sabbatical. I thought, ‘This is the new me.’ I thought that’s the way my life was going to be. I was leaving behind that other stuff. I’m a photographer in Magnum Photos, which is a well-known photo agency often associated with war photographers. I’ve never been that kind of photographer, but I’m out in the world, racing around, documenting, and I thought, ‘Yeah, I’m done with that kind of activity.’ It wasn’t out of a negative energy. It was actually out of a positive energy of a sort of quasi-spiritual experience. I just wanted to connect with nature and nature things and not be in that mud of human conflict.

Ann—Did you feel that it was beneficial to your practice to take this moment of pause?

Alec—It was totally rejuvenating, and it was a real question as to whether or not I would go back to regular old photography. Eventually, I started doing this experimental stuff with other people. I was just kind of playing with them, and this led me to start photographing again. One of the people that I encountered very early on is Anna Halprin, this legendary choreographer, who’s made a career out of knowing how to play in space with other people. That encounter, it’s not like we were playing. It was a normal photographic kind of session, but I felt rejuvenated from this time away and thought that I could approach portraiture in a slightly softer, more open, way.

Ann—You cited Peter Hujar’s work as one of your influences. When did you first discover his photography?

Alec—Really, really, really early on. A long time ago. It’s interesting because maybe 10 to 15 years ago, I was asked to name my favorite photographer, and I named him. It was even weird to myself. I was like, ‘Wow, that’s a strange answer,’ because he wasn’t a project photographer the way that I am. He wasn’t a narrative photographer. He put lots of pictures together in book form. He was more about the individual image and the individual print, but his quality of intimacy is something I have always really admired.

Ann—You used to do these projects where you would photograph geography and communities. You used to take a macro look at the world, and now you’re looking at a more micro aspect through the individual. Why the transition?

Alec—I had this kind of spiritual experience. I think that everybody has this kind of thing—where you’re, like, having your coffee in the morning or whatever, and the light is hitting just right, and you’re not thinking about anything, and you’re focused. You’re just totally immersed in something. It’s so specific in the way that you can lose yourself in that moment. I just had this awareness of how precious that is. It seemed like talking about economics and class and politics and all of this stuff would take me out of that moment. Originally, I was having that kind of moment in solitude, and then I was trying to have moments like that in the intimacy of another person’s room. It’s not always like that, but I just wanted a moment where you could touch another person in a way.

Ann—Once you decided to do this series, how did you select your subjects? They seem pretty diverse.

Alec—I decided, ‘I’m not really going to pick the location. I’m just going to respond to invitations.’ I get asked to go to different places and give a lecture or have a show. So I would just say yes. I had a year of saying yes to those things. I would find somebody in that spot before I would go to that place. I would tell them what I was up to and that I was looking to have these kind of intimate exchanges and ask for suggestions. Then they would send me information—pictures of people, social media, what have you. And I would try to get a read on who I might like to spend time with. I set up these sessions, and it’s a strange thing. It’s like a portrait session. It’s from home. It’s a therapy session. It’s this weird intimacy. Sometimes you don’t speak the same language.

Ann—You cited Walker Evans’ book that had both interiors—

Alec—Yeah, Message from the Interiors.

Ann—Yeah. It had both interiors and portraits. In the book, in your interview with Hanya Yanagihara you discussed your desire to peer into houses when you were a Chinese food delivery man. Why is it so gratifying to see the way in which other people live?

Alec—I’m a photographer. That’s such a key pleasure. But there’s an element of like, when you look at how someone else lives, you look at how you live. We’re all trying to figure out how to live.

Ann—Yes.

Alec—That’s universal. It’s just sort of fascinating. When I’m in someone else’s house—what kind of books do they have? What are they reading? It’s just another way to try to glean who this person is. What’s going on inside of them? We only have so many clues. We see how people dress. We see their mannerisms. And an interior provides all of this other information.

Ann—I saw your photo of Keni at The Armory Show in Sean Kelly’s booth. Can you tell me more about that experience?

Alec—What was Keni like? I mean, that was atypical of a lot of the pictures in that—so Keni was a bit more apprehensive than some of the people that I photographed. We met ahead of time in a coffee shop, and that was the opportunity to really sort of let the thing settle. And then, Keni didn’t want me in their space. So it was just a bit different. I was staying at an AirBnB, and that’s where that picture was made. So they came over, and it was a bit different because Keni was much more self-aware of presentation.

Ann—What does Keni do?

Alec—I don’t know what Keni does.

Ann—Interesting.

Alec—Yeah, he was just very fashionable.

Ann—You said in your interview with Haniya, ‘Enough is enough with the ego gratification’” I mean, I know we work around creative people, and there are always these egos running around, and they’re not happy until they get what they want. What led you to tame your ego?

Alec—It’s a great question, but I also feel like a piece of shit fraud answering that question because I’m doing a fucking interview, and it’s like, ‘Me, me, me, more me.’ And I’m in it again. [Laughs]. I’m like, ‘Here I go again.’ I’m very conflicted about this because, when I was talking to Haniya I was in a really good state of mind. I was just in the making of work and having these experiences. And now I’m in the promotion of the work, and just getting it out there, and it’s just very problematic, and I haven’t solved that. I’m fascinated with the role of ego in art, you know?

Ann—Hell yeah! [Laughs.]

Alec—Because it’s an engine, for sure. It’s why so many of us pound the pavement to get the work out there and to get seen. But you can lose yourself in that for sure. I don’t think I’ve ever lost myself in it, but I just feel that current. It’s like there’s a waterfall down there, and it’s, like, swing to the edge quick or you go over that waterfall. It’s dangerous.

Ann—Yeah. [Laughs.] How did you discover the poem where you got the title of your series, “The Grey Room”?

Alec—So I’ve read Wallace Stevens forever. He is just so great in dealing with consciousness. Just in thinking about consciousness. You know, we’re talking about ego, and what is the self, and all that kind of stuff. So, poetically, he just deals with it. I very often am turning to poetry for help in understanding whatever photographic predicament I’m in. In this case, I’m making this work about being in a room with another person. And of course, Wallace Stevens has the perfect poem about the subject and the perfect string or words.

Ann—You talked about Diane Arbus and exploitation. Last year I saw an exhibition of one photographer, and he photographed marginalized domestic workers. That photograph was selling for $90,000 and he stood to make, what, $45,000 if it sold? Let’s talk about photographers and exploitation. When is the line crossed?

Alec—Everyone draws their own line. I make the analogy to eating meat. I always ate meat and then I went through a change, and I stopped eating meat but I wasn’t a vegan. Then after a year of that, I started eating meat. But it’s more farm-raised. I check out the background, that kind of thing. It’s more like these moving lines. And we all have to do this in different ways.

Ann—Yeah.

Alec—If I’m going to photograph people, I have to figure out what that line is. Is it what Bruce Gilden does? Do I make it totally collaborative? And the subject chooses which picture I make, and styles and does everything for it? In the end, this is what I’m grappling with. For a period of time, I was like, ‘That’s it. I’m done with it. I’m a vegan. I’m done.’ And now, I [am] eating meat again but trying to make it more ethically conscious.

Ann—How do you define what your own responsibility is as a photographer?

Alec—It’s an evolving question. I like people to be aware of how these things can be used. I always ask people for permission. Well, I mean, most of the time. There’s this one big project that’s an exception, but I ask people to take their picture. I explain what they’re for, but I didn’t know that the [Sleeping by the Mississippi] pictures were going to be in the Whitney Biennial. I was a nobody…something does change if it ends up being that picture on the wall. Suddenly, that’s different. And I’m just starting to reflect on the meaning of that again because I can’t put out of my mind this moment where all this work is revealed and enters the commercial world.

Ann—Do you still meditate?

Alec—Oh yeah. All the time. But it’s nothing special. It’s like brushing your teeth.

Ann—And does it actually clear your head and make you feel centered?

Alec—No.

Ann—[Laughs]

Alec—It helps. I mean… oh god! Anyone who reads anything out of all this starts meditating. Yeah. It’s the best, but it doesn’t cure. It’s no cure for anything. It just helps. And you live in Brooklyn! Get on the meditation!

Ann—I can’t! My mind’s too noisy!

Alec—Everyone says that.

Ann—[Laughs]

Alec—No, really! That’s what every single person says. And the whole point of meditation is not to stop thinking. It’s to understand how the noisiness of your mind works. You have to be the most badass meditator in the world to go for ten seconds without thinking. It’s really hard. But you can slow it down a little and have a little more awareness of when it’s taking over. Trust me.