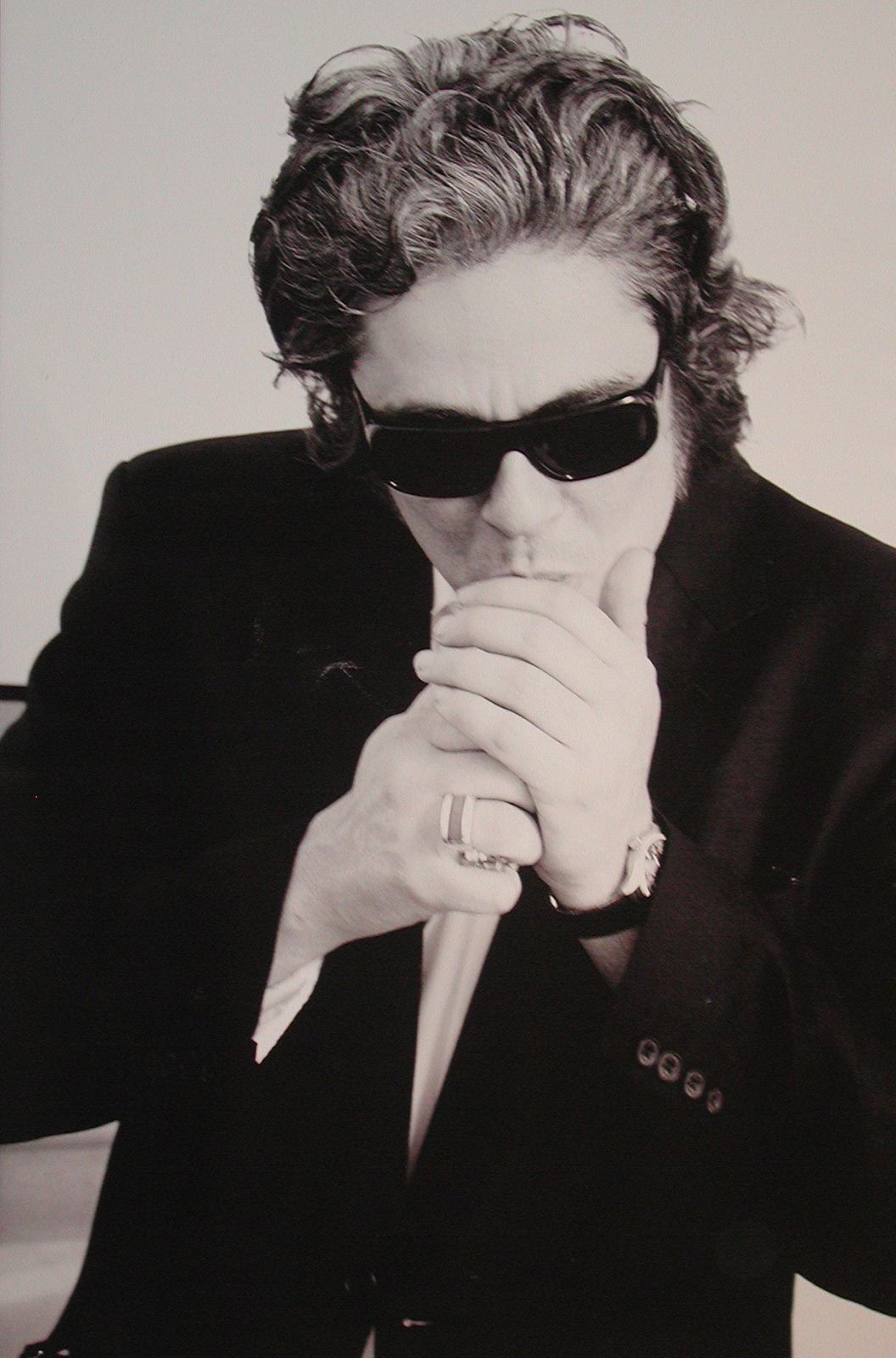

Galerie Gmurzynska pays homage to Karl Lagerfeld, the photographer, with a retrospective featuring 30 years of his work.

Karl Lagerfeld may have earned icon status as the designer at the helm of Chanel for the last 35 years, or as the creative director of Fendi for the last 53 years, or even as the designer behind his eponymous label since 1984, but he was also a renaissance man who often devoted himself to other creative projects. Lagerfeld also collaborated with brands like Diet Coke, for which he designed striped and dotted bottles; and the European ice cream brand Magnum, for which he directed a commercial starring Rachel Bilson.

One of his passions outside of design was photography; Lagerfeld would often shoot Chanel’s campaigns, and he also photographed editorials for magazines like V, Numéro, and Harper’s Bazaar. “What I like about photographs is that they capture a moment that‘s gone forever, impossible to reproduce,” Lagerfeld once said. In 1996, Lagerfeld’s photography caught the attention of the Zurich-based Galerie Gmurzynska, which shows blue-chip artists like Pablo Picasso, Yves Klein, and Kurt Schwitters, and they immediately signed Lagerfeld to their roster. The gallery, which was the first to show his work, has represented the designer for the last two decades.

To honor Lagerfeld, who passed away on February 19 at age 85, Galerie Gmurzynska is exhibiting a retrospective of the fashion legend’s photographs: Homage to Karl Lagerfeld: 30 Years of Photographythrough May 15. The show highlights Lagerfeld’s photographic oeuvre, from portraits of celebrities like Jack Black and Nicole Kidman, to black-and-white details shots of the Eiffel Tower, to close-ups of the intricacies of building façades. Document caught up with art dealer Mathias Rastorfer, who worked closely with Lagerfeld at Galerie Gmurzynska, to discuss Lagerfeld’s favorite artist, his techniques, and the one time he showed up to his own opening six hours late.

Ann Binlot—How did Karl Lagerfeld and Galerie Gmurzynska start working together?

Mathias Rastorfer—We worked with Karl for over two decades since 1996, and were, in fact, the very first gallery to show his work. When we started to be the first to show his photography publicly in 1996 we were criticized for it, being a well-established gallery with over 55 years of history and a serious reputation for art historical research in Classic Modern Art. Today we have requests from important museums and collectors around the world to show and acquire Karl Lagerfeld’s photography.

Ann—Where and when did you first meet Mr. Lagerfeld? What was he like?

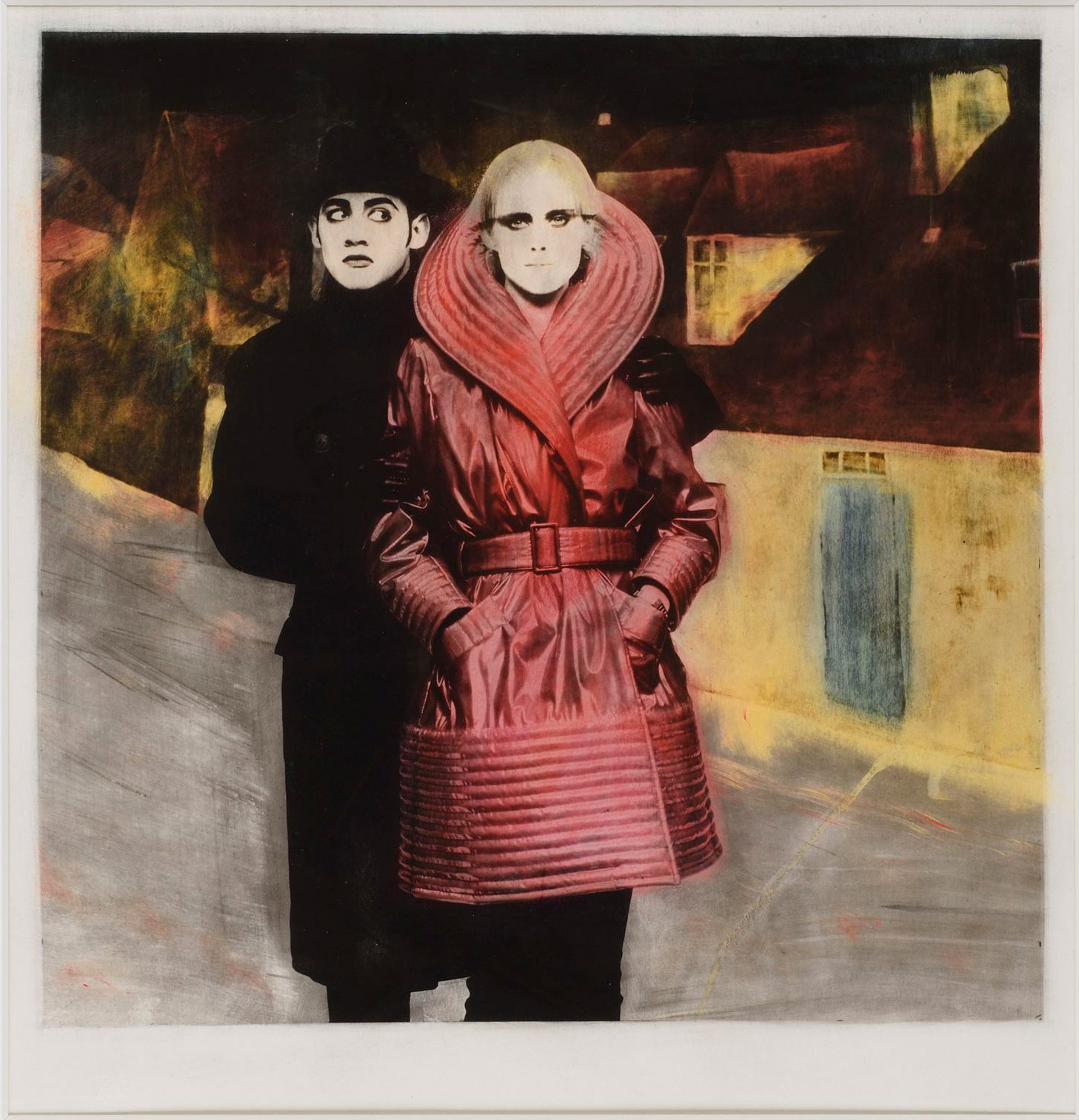

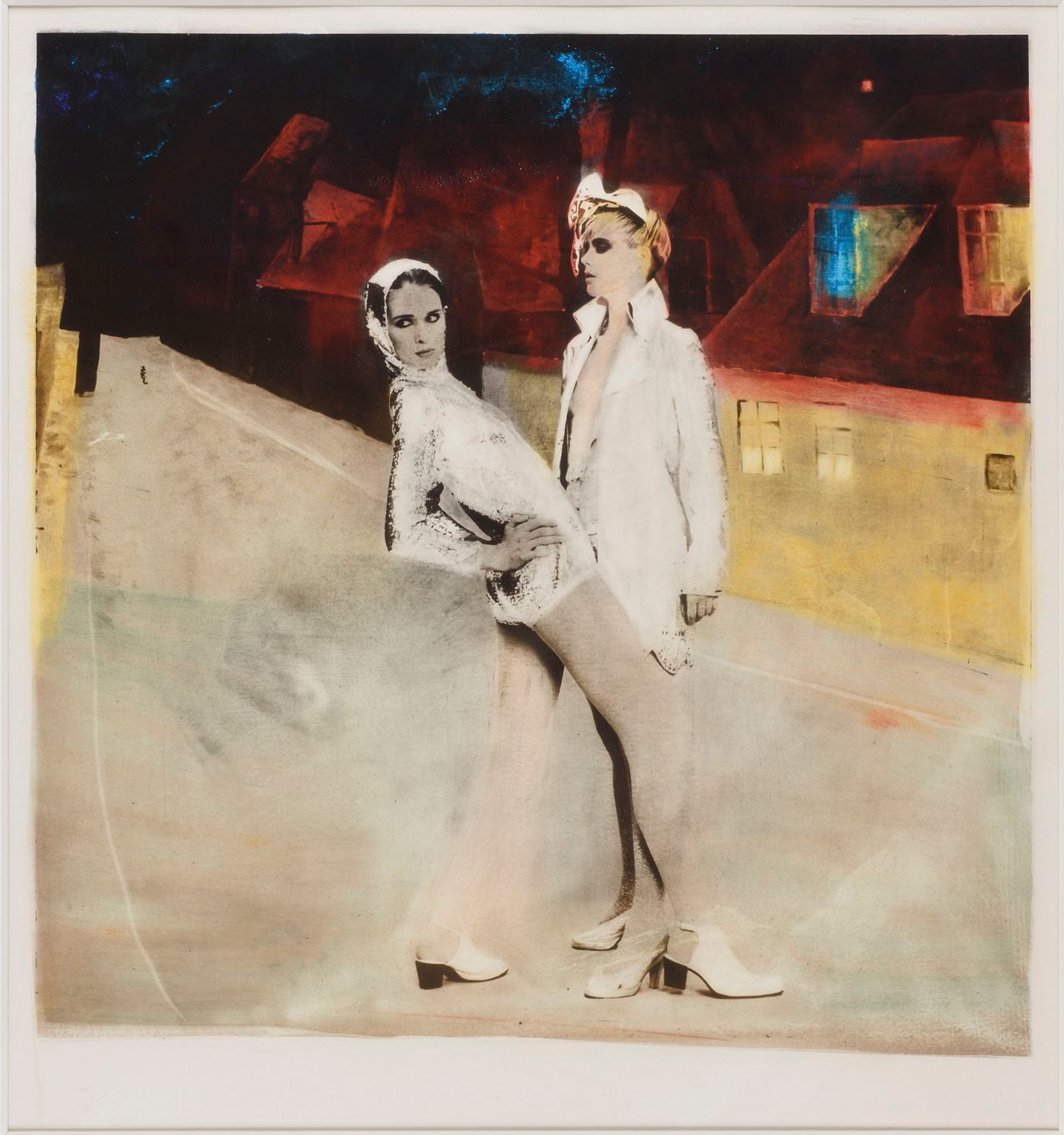

Mathias—Our close relationship with Karl dates back to the early 1990s. He was a connoisseur and collector who admired our exhibitions and publications. In 1996 we spoke with him about his love for the work of [German-American Expressionist artist] Lyonel Feininger from the 1910s and ’20s and his interest in publications of the time like Simplicissimus. One thing led to another and we decided to mount an exhibition of his photographs inspired by Feininger next to original works by Feininger from the first part of the 20th century. The exhibition was an incredible success and the rest is history…

Ann—What was his approach to photography? What made his aesthetic his own?

Mathias—Karl was what I would call a Renaissance Man. He had many cultural interests and a connoisseur knowledge about it. Photography was important to him and a favorite medium to express himself.

Ann—To what kind of subjects did he gravitate?

Mathias—Karl shared with us a deep curiosity for rediscovering artistic talent from the past that had been overlooked today. Artists that contributed greatly to art history at their time and whose work still matters today, but might be misrepresented. Diamonds in the rough, so to speak. Juxtaposing Karl’s photographic homage to Feininger next to historic work by Feininger was such a collaboration.

Ann—What did his photography reveal about himself?

Mathias—Karl was a very generous person who had one precious commodity and that was time. When we apologized if it would be ok to disturb him for a meeting on a Sunday he would respond by saying, ‘We are not public servants, what is Sunday?’ On the other hand, when we did an exhibition of his in our St. Moritz gallery, due to a late departure and a late arrival, Karl came six hours after the highly feted lunch, when most people were already gone. Upon entering the gallery he said, ‘What is worth waiting for…?’ The ones who had the luck to know Karl a bit better knew that he was never arrogant, simply very selective in how he spent his time, and time with Karl was never wasted.

Ann—What photographers did he admire the most?

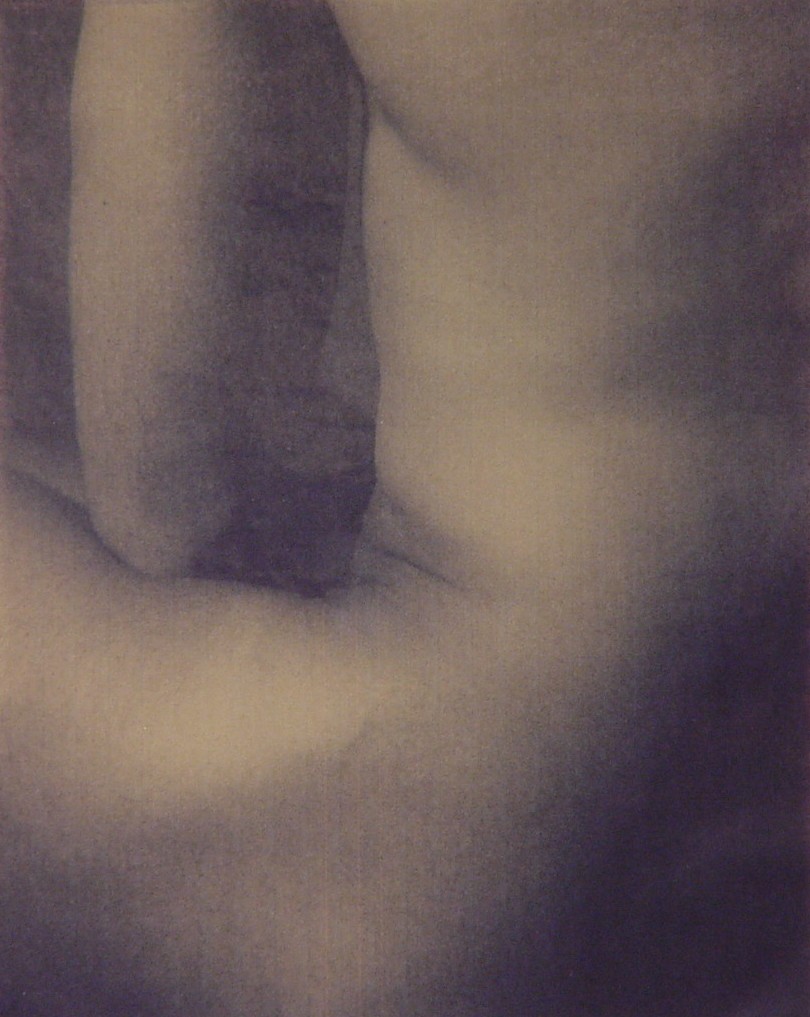

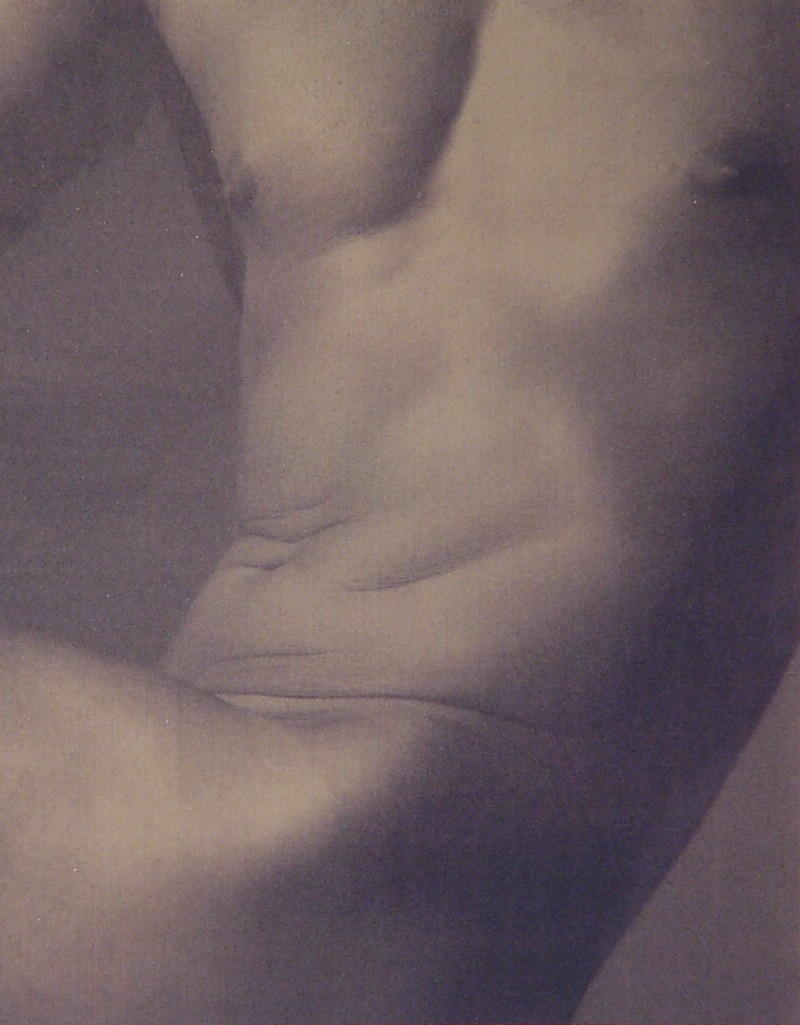

Mathias—Karl was fascinated by techniques that were either rediscovered from the past or cutting edge of the future. In this context, for the Feininger photos, he used a 1900 technique to hand color a black-and-white photograph with pigment and a mixture of honey and rubber on handmade paper. The effect is magic. Or, he used the largest Polaroid camera at the time (of which there were only three in the world) to make instant and totally unique large scale Polaroid images. These are unique in both technicality and beauty.

Ann—What was your dealer-artist relationship like with him?

Mathias—Krystyna Gmurzynska and myself were personally close to him. We wanted to honor this long collaboration and this man whom we regarded as one of the last true renaissance genius. We were all incredibly saddened by his passing and spontaneously wanted to show our respect for Karl by remembering our two decades of collaboration, showing a wider public his lesser known passion for photography.