As gender moves beyond the binary, Document takes a look at toxic and beautiful permutations of masculinity with Slava Mogutin, Jan Philipzen, David Uzochukwu, Soraya Zaman, and Kamau Wainaina.

Underlying the debates over reproductive rights, the right to healthcare for queer individuals, or the latest misogynic soundbite hurled by the 45th president, lies the thorny subject of masculinity. Whether termed “toxic,” “traditional,” or “violent,” the topic rears its head in controversies across industries, from journalism and politics to fashion and the arts, often involving the transgressions of male industry leaders. But even as individual stories move in and out of the spotlight, the thorny subject of masculinity remains at play.

The recent release of the American Psychological Association’s “Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Boys and Men” elevates the subject to a public health concern. The guide urges medical professionals to consider the consequences of internalized masculine social norms when treating patients, particularly in situations involving mental health. The guide triggered various responses, some praising the proactivity of these measures while others criticized the implication that aspects of masculinity might be fundamentally harmful.

With this conversation in the periphery, Document asked five photographers to comment upon their experience of toxic, traditional, and beautiful permutations of masculinity. As society and culture evolve beyond the gender binary, their artistic practices navigate and challenge long-held beliefs about gender performance, violence, and self expression and the work still undone.

Clara Malley—What comes to mind when you think of masculinity?

David Uzochukwu—As a set of values – at best, directness, courage, a sense of responsibility to provide. But this describes many people who are not men, and definitely not all men.

Clara—Do you believe masculinity can be toxic?

David—Masculinity seems harmful to me when it stands in radical opposition to femininity. When focussed on self assertion, it allows for disregarding others and avoiding self confrontation. Negating a range of emotions, because softness is feminine, can not be healthy. The ideal of pure masculinity is unbalanced in a way that does not do justice to a human’s inner workings.

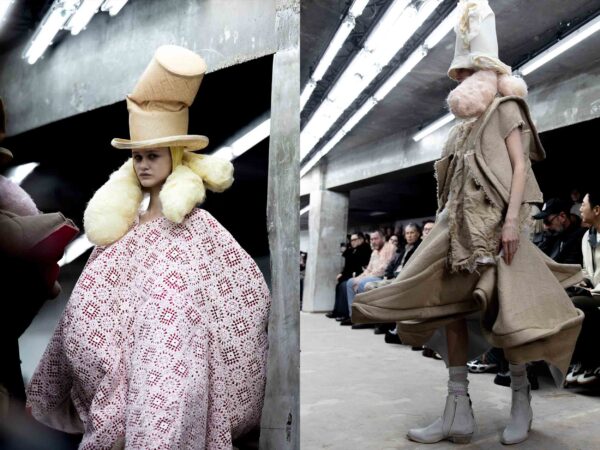

Clara—Do you see interpretations of masculinity shifting in your industry as interpretations of femininity and queerness evolve?

David—I see individuals acknowledging issues arising from our current understanding of masculinity [such as] Ryan Caruther’s “Tryouts,” Sam Fenders and Vincent Haycock’s “Dead Boys,” and people carving out a space for their interpretation of masculinity, whether consciously or unconsciously (Ib Kamara’s entire body of work ). Even within the arts change could come faster – and they are far from representative for the state of all industries.

I believe that evolution of our societies’ view on queerness is largely tied to removing stigma attached to femininity. It seems to me that any change of what masculinity means has to be directly linked to this process, too.

Clara—What comes to mind when you think of masculinity?

Slava Mogutin—I grew up in a culture where masculinity is traditionally associated with uniforms. It’s not a coincidence in Russia, where they have a two-year compulsory military service. I learnt how to operate AK-47 as part of my school education, but I wasn’t drafted because I told them I was a homosexual. In a paramilitary society like Russia, uniform is what makes a man a man—not his talents or character. My young nephew told me he wanted to become a cop and when I asked why, he said because he could wear the uniform. As David Bowie put it, “When you’re a boy you can wear a uniform, when you’re a boy other boys check you out.”

Clara—Do you believe masculinity can be toxic?

Slava—I always say that too much testosterone is a recipe for disaster. In a way, we’re all hostages of the toxic masculinity of our political leaders, authority figures and business moguls. It basically shapes the cultural and political climate in the majority of countries. According to the recent UN data, males account for about 96 percent of all homicide perpetrators and 79 percent of the victims worldwide. Numbers like that are where you really see toxic masculinity in action!

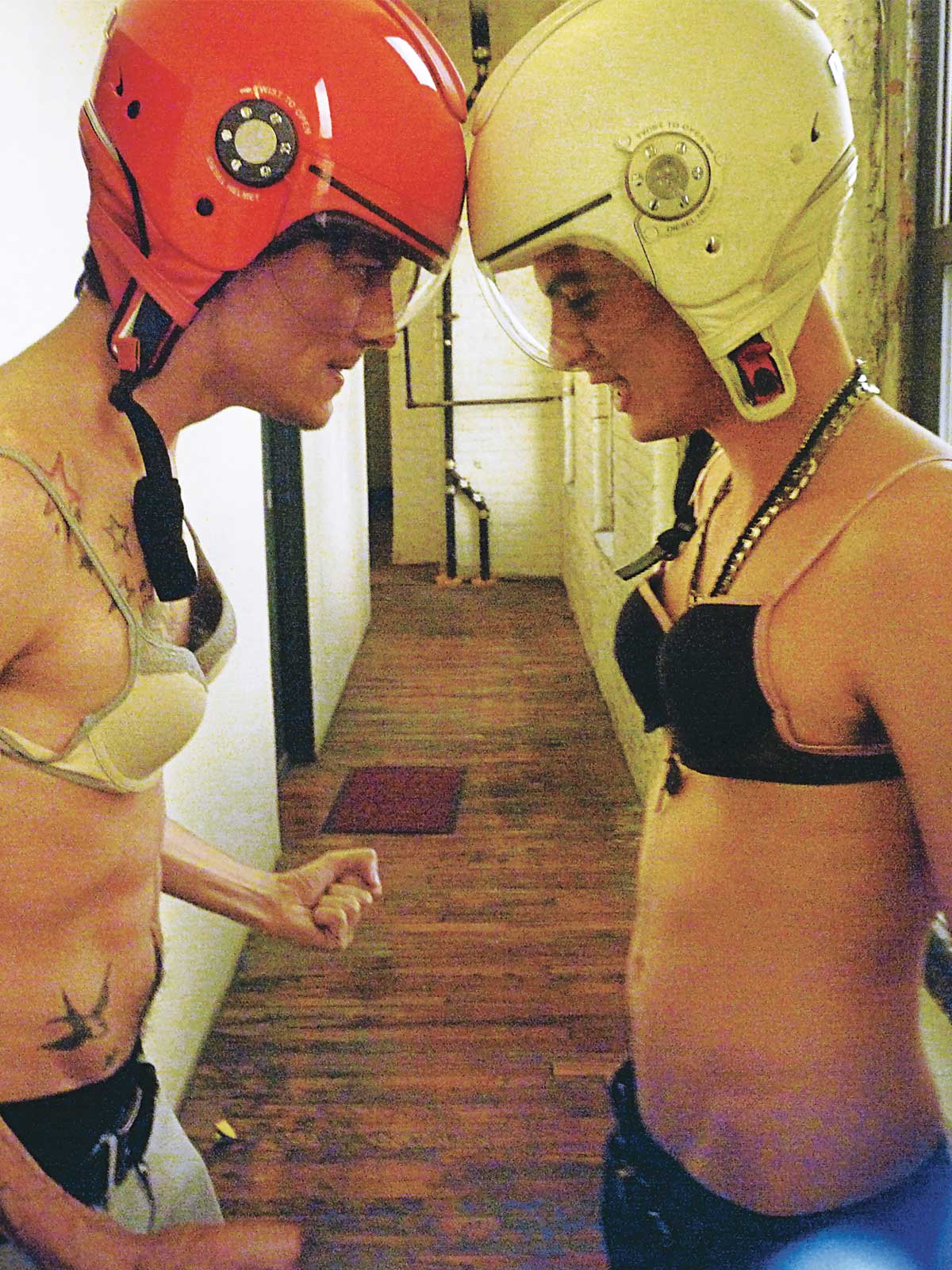

Clara—How does your work engage with traditionally defined masculinity—strength, stoicism, perhaps violence?

Slava—I often reference masculine archetypes as a way to understand what really makes a man a man. It’s like decoding the codes of machismo, tearing up the façade and trying to find out what hides underneath. For example, look at my photos of gay German skinheads bonding, showing off and urinating on each other. In a country with a Nazi past, it’s a double transgression to be a gay skinhead. What’s the appeal behind adapting your enemy’s identity and subverting it? What makes violence and aggression so appealing to straight and gay men alike? Do muscles make us empowered or lead us to body fascism? These are some of the questions that I’m trying to raise through my work.

Clara—What comes to mind when you think of masculinity?

Jan Philipzen—It’s a sometimes seemingly paradoxical balancing act I would say.

Clara—Do you believe masculinity can be toxic?

Jan—Yes I believe that certain behaviours which are attributed to masculinity can be toxic. But I think it is also very important to emphasise that it always depends on the application. Self-reliance for example is a good thing, when you are alone in a foreign city. Meanwhile it’s a terrible idea to refuse help when it comes to physical and mental illness, because of one’s desire for self-reliance.

Clara—How does your work engage with traditionally defined masculinity—strength, stoicism, perhaps violence?

Jan—I definitely engage with aspects of traditionally defined masculinity, but not necessarily under the umbrella of masculinity. I engage with violence for instance more as an exploration of the Nietzschean idea of the Dionysian. An exploratory journey which I find quite common in art and music, especially in an era where minor keyed songs about drugs and dark ecstatic techno music heavily influence popular culture.

Clara—How does your work engage with traditionally defined masculinity—strength, stoicism, perhaps violence?

Kamau Wainaina—A lot of my work is family-related, trying to document loved ones organically so as to better understand them and my connection to them, and subsequently what my Kenyanness looks like in its fluidity and various branches. There’s a lot of tension that arises when family becomes subject and a lot of work has pushed me to ask questions that reveal the toxicity that surrounds Kenyan culture. When my maternal grandfather died I was taking photos throughout the whole funeral and burial process, as my mother’s side experienced an intense grief that came with confronting the great and awful things that my grandfather Ike had done and been. As Kenyans, and by extension Africans, attempt to grow and self-actualize there’s a need to confront the toxic masculinity that exists at the root of a lot of cultural elements.

Clara—How does your work deconstruct this understanding, if you feel it does?

Kamau—I don’t feel that my visual work goes out of its way to specifically deconstruct masculinity as much as others, but in trying to capture different African/Kenyan and Black identities, I’ve found that capturing younger men and boys both within my family and throughout the continent has given interesting insight into how masculinity is quietly imposed and deconstructed. I hope to do more in the future though, as I delve more into the makings of my masculinity.

Clara—Do you see interpretations of masculinity shifting in your industry as interpretations of femininity and queerness evolve?

Kamau—I definitely see things changing, more so in visibility than anything else. The danger of evolution within the arts is that it can remain quite surface level, not reaching the production and practice – and how we treat and recognize queer and femme artists as well as subject matter that discusses those experiences. There’s still a long ways to go, which includes not just embracing the current winds of change but recognizing and amplifying the histories of these other narratives so when things like the APA Guidelines arise we can recognize the importance of listening and self-critique as men, rather than rushing to defend an inherently oppressive masculine culture.

Clara—Do you believe masculinity can be toxic?

Soraya Zaman—Yes, absolutely. Masculinity is a performance and so too is toxic masculinity. By upholding these performative behaviors and guidelines for what it means to “be a man”, we are not allowing people to find their authentic and true gender expression which in turn, is oppressive and toxic. Queer people are not immune to toxic masculinity and are also guilty of perpetuating gendered stereotypes. For instance, cis gay men who live ostensibly heteronormative, hyper-masculine lives to reduce the feelings of being part of a minority group for an example or even the drag king community, which has been called out for replicating toxic masculinity. It just shows how pervasive our social construct is. Masculinity can be reimagined. Crying can by masculine, wearing a dress can be masculine, expressing your feelings and being vulnerable can be masculine, anything can be masculine! It’s just what society associates with these words with that gives them their meaning. The challenge is for all of us, queers included, to think outside of the mental binary.

Clara—How does your work engage with traditionally defined masculinity—strength, stoicism, perhaps violence?

Soraya—I think my project and book, American Boys, engages with traditional understandings of masculinity by directly challenging them. The project title is an intentional call out to this nostalgic, almost patriotic idea of American boyhood and the notion that masculinity belongs exclusively to cis men. The work centers and celebrates transmasculine individuals across the country through a series of portraits and essays. It unpacks this belief that gender identity must align with one’s sex assigned at birth and embodies different interpretations of masculinity. I also hope it allows people to look and challenge the way they themselves perceive traditional binary gender roles.

Clara—Do you see interpretations of masculinity shifting in your industry as interpretations of femininity and queerness evolve?

Soraya—The way we think and talk about masculinity is changing but has a long way to go. The representation of masculine presenting queer, trans, and gender non-conforming folx is definitely lagging and when you reach beyond just the model and talent level to consider all aspects of the industry, from magazines, photographers, photography agencies, designers, creatives, brands etc., there is a little representation. These aspects are still steeped in cis heteronormativity.