Amira Rasool remembers five figures who sacrificed their lives in the United States in the fight for civil rights and social justice.

Black History Month is a time for reflection and celebration. It’s a time when politicians from each party heavily recite quotes from Martin Luther King Jr. and hold memorials to honor the legacy of Rosa Parks. It’s a time when educators curate a curriculum to acknowledge the brave sacrifices of abolitionists Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman, and the glowing accomplishments of Black athletes Jackie Robinson and Jesse Owens. Year after year during this compact month, the same names and quotes of black-American icons are, deservedly or not, regurgitated to no end.

The memorializing of these particular black historical figures is no coincidence. The heroes prominently recognized in mainstream black history texts are often non-violent, mild-mannered, and proud Americans who lived in the country without significant public scandal. They often favored integration, cross-racial cooperation, and a nationalist approach to civil rights advocacy. Although these well-behaved individuals contributed significantly to the fight against racial oppression, it’s the names that most Americans don’t recognize that shook the US government and its policies to its core. These are the people who sometimes had to sacrifice their ability to reside in the US and instead face a life abroad, away from their homes and loved ones, in order to continue the fight to end racial oppression and violence.

The concept of out-of-sight, out-of–mind has done much to diminish and erase the legacy of black historical figures who experienced such fate. Despite the impact black activists like Kwame Ture, Robert F. Williams, and Claudia Jones had on advancing the conditions and consciousness of black-American people, their extended absence from the US as a result of political exile significantly reduced their chances of being notably documented in historical texts and public discourse. Additionally, the radical communist, pro-violence, and segregationist views that initially made them vulnerable to political persecution, also led to their erasure from historical narratives because they fell outside of the traditional ideology promoted by the favored non-violent, mild-mannered, black American.

Above The Fold

A Weekend in Berlin

Georgia Hilmer’s Fashion Month, Part One

An Olfactory Memory Inspires Jason Wu’s First Fragrance

Introducing: Cecilie Bahnsen, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Of course, the names of politically exiled black historical figures consistently remain on the tongues of many history buffs. Approach any African-American studies major and discuss W.E.B. Du Bois and a quote from The Souls of Black Folk will surely follow. However, it is important that this particular type of black-American activist is not excluded from everyday historical conversations and that they are acknowledged by a greater mass of the public. By recognizing black Americans who experienced political exile, we can ensure that their banishment from the United States is not an indefinite part of their legacy and finally returns their stories back to the country from which they were forced to leave.

Kwame Ture

“It is a call for black people in this country to unite, to recognize their heritage, to build a sense of community. It is a call for black people to define their own goals, to lead their own organizations.”

—Kwame Ture

At the beginning of the 1960s, Kwame Ture (born Stokely Carmichael) was a bright-eyed college student looking to desegregate the south and eradicate racism through non-violent protests. Within six years, the former chairman of SNCC, no longer subscribed to the ideas of non-violence. Ture, an extremely skilled orator, made speeches advocating for “Black Power,” a phrase he popularized in 1966 to encourage black people to collectively seek their own social, economic, and political autonomy, without white participation. His sudden transition from non-violent activist to a member of the Black Panther Party came with an immense set of consequences. In the media, Ture, along with other members of the party, were cast as menacing figures whose ideas of Black Power were a threat to the peaceful wellbeing of America. As a target of the FBI’s Cointelpro operation, Ture experienced heavy surveillance by the FBI. The pressures he faced as an FBI target eventually forced Ture to flee the US and settle in Ghana, and later Guinea, where he became a huge proponent of Pan-Africanism and spoke of the need for African people around the world to unite to resist racial oppression and celebrate African heritage.

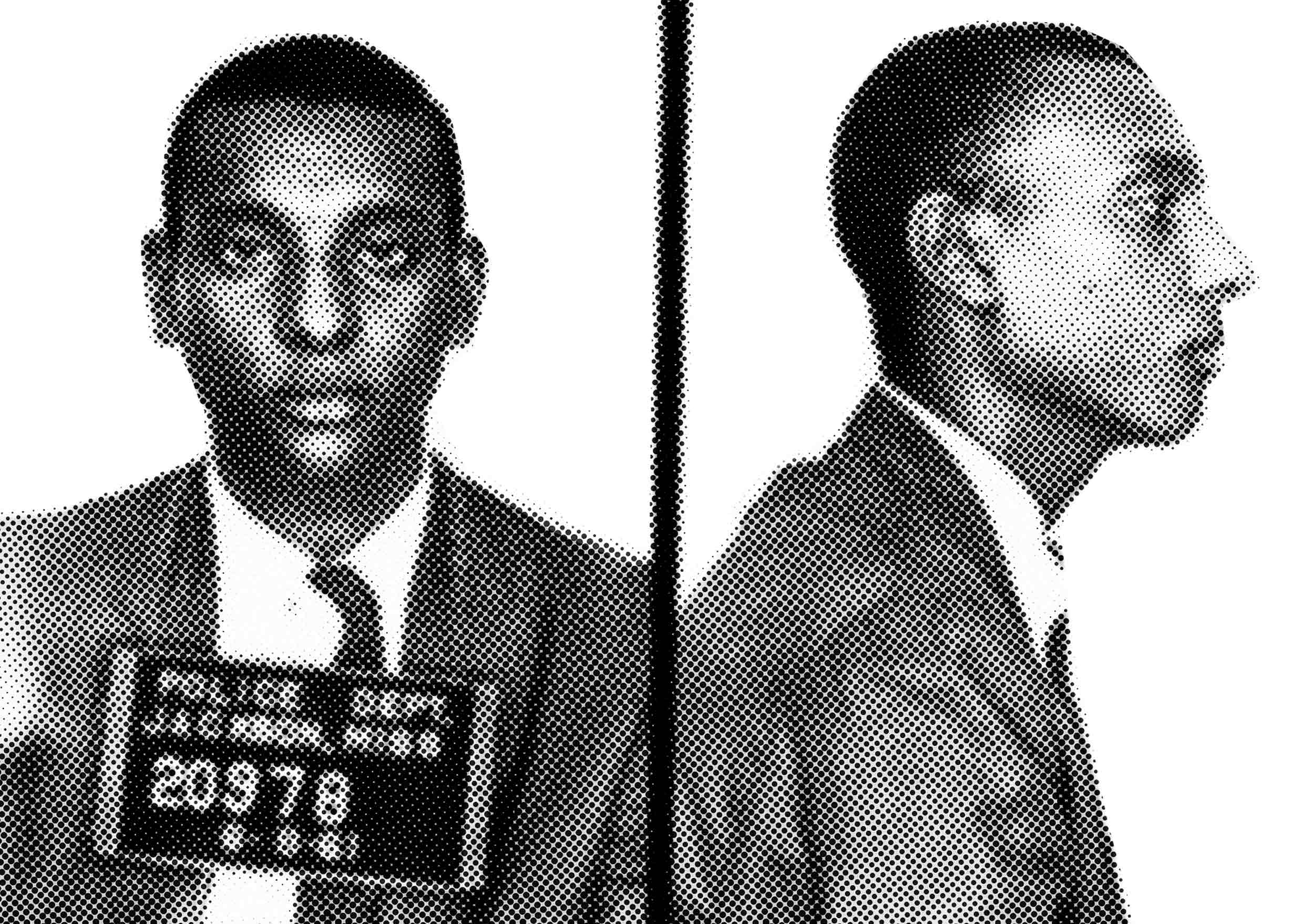

Robert F. Williams

“That there is no law here, there is no need to take the white attackers to the courts because they will go free and that the federal government is not coming to the aid of people who are oppressed, and it is time for Negro men to stand up and be men and if it is necessary for us to die we must be willing to die. If it is necessary for us to kill we must be willing to kill.”

—Robert F. Williams

According to PBS, activist Robert F. Williams was the first prominent black-American civil rights leader to champion armed resistance in the fight to end racial oppression and violence. During his tenure leading a local North Carolina chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Williams formed the Black Guard, an organization committed to using weapons to protect the Black community from violent attacks by the Ku Klux Klan. The idea of Black men preparing to combat racial violence with violence did not sit well with white people or members of mainstream civil rights organizations that advocated for non-violent resistance. After being outed by the NAACP for his pro-violence advocacy, Williams was eventually forced to flee town after being accused of kidnapping two white Freedom Fighters that he rescued from a violent attack. He spent five years with his family living in Cuba, where he was granted political asylum and another extended period in China. While exiled, Williams wrote the infamous book, Negroes With Guns. The book would eventually influence Black Panther co-founder Huey P. Newton and other young radical leaders interested in armed resistance.

Claudia Jones

“The Lady with the Lamp, the Statue of Liberty, stands in New York Harbour. Her back is squarely turned on the USA. It’s no wonder, considering what she would have to look upon. She would weep, if she had to face this way.”

—Claudia Jones

Journalist Claudia Jones was an intersectional feminist long before civil rights scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw first coined the term in 1989. The Trinidadian-born, Harlem-raised activist spent much of her adult life fighting for the empowerment of marginalized people, in particular, those who were marginalized as a result of race, gender, and economic biases. She publicly petitioned for the inclusion of women in liberation movements and warned that any anti-oppression movements that did not include women or address economic exploitation would fail. Her beliefs, influenced by her childhood experiences with racism and poverty, led her to join the Young Communist League and closely study the science of Marxism-Leninism. Throughout the three decades she spent in America, Jones helped communist and civil rights groups organize resistance movements. In 1955 following several stints in jail as a result of the anti-communist Smith and McCarran Acts, the US deemed Jones un-American and deported her to Britain under the condition that she was a “subject of the British Empire” (Trinidad was a British colony at the time). She would go on to lead several iconic social movements in the UK.

W.E.B. Du Bois

“The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line: the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea.”

—W.E.B. Du Bois

Scholar and activist W.E.B. Du Bois is often heralded as one of the most prolific thinkers of the 20th century. As a trained sociologist and one of the founding members of the NAACP, Du Bois combined his knowledge of sociology with his passion for analyzing the vial conditions Black people faced under America’s racially oppressive systems. One of his most noted literary contributions was The Souls of Black Folk, a collection of essays that examined the social conditions of back Americans and problematized race in the US. Throughout his adult life, Du Bois wrote a series of books and gave speeches calling for the dismantlement of racism. He also became an outspoken proponent of communism and eventually joined the American Communist Party. His advocacy for Black Americans’ liberation and his communist ties led to the suspension of his passport for several years. Following the restoration of his passport, Du Bois accepted an invitation to Ghana to join the growing Pan-African movement spearheaded by president Kwame Nkrumah. He spent the remainder of his life in Ghana advocating for global African unity, and eventually renounced his American citizenship to become a citizen of Ghana after the US declined to renew his passport.

Ida B. Wells

“The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.”

—Ida B. Wells

The formerly enslaved activist, Ida B. Wells, was one of the most prolific journalists of the 19th and 20th centuries. Her work detailing lynchings in the deep south exposed international audiences to the vile nature of America’s violent acts of racism. Wells, as both a race and feminist activist, spent a significant amount of time traveling around Europe giving speeches about lynching and urging women’s rights movements to recognize lynching and other forms of racial oppression. She advocated for black people to engage in violent resistance if faced with the threat of racial violence. Because of her radical views and the significant amount of international scrutiny her anti-lynching crusade summoned, she was continuously targeted in the US and a victim of many threats and assassination attempts. Wells eventually settled in the UK and certain parts of the north for extended periods of time and didn’t return back to the south for over 30 years. Although Wells’ time outside of the States was not a government-sanctioned exile, her writings and speeches made her unable to safely live or travel in the south, and the U.S. government and law enforcement officials did not do much to quell this threat.