As gender moves beyond the binary, Document takes a look at toxic and beautiful permutations of masculinity with Liana Finck, Rashaad Newsome, Cédric Rivrain, Gianni Lee, and Amber Vittoria.

Underlying the debates over reproductive rights, the right to healthcare for queer individuals, or the latest misogynic soundbite hurled by the 45th president, lies the thorny subject of masculinity. Whether termed “toxic,” “traditional,” or “violent,” the topic rears its head in controversies across industries, from journalism and politics to fashion and the arts, often involving the transgressions of male industry leaders. But even as individual stories move in and out of the spotlight, the thorny subject of masculinity remains at play.

The recent release of the American Psychological Association’s “Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Boys and Men” elevates the subject to a public health concern. The guide urges medical professionals to consider the consequences of internalized masculine social norms when treating patients, particularly in situations involving mental health. The guide triggered various responses, some praising the proactivity of these measures while others criticized the implication that aspects of masculinity might be fundamentally harmful.

With this conversation in the periphery, Document asked four artists to comment upon their experience as part of an ongoing series exploring toxic, traditional, and beautiful permutations of masculinity. As society and culture evolve beyond the gender binary, their artistic practices navigate and challenge long-held beliefs about gender performance, violence, and self expression and the work still undone.

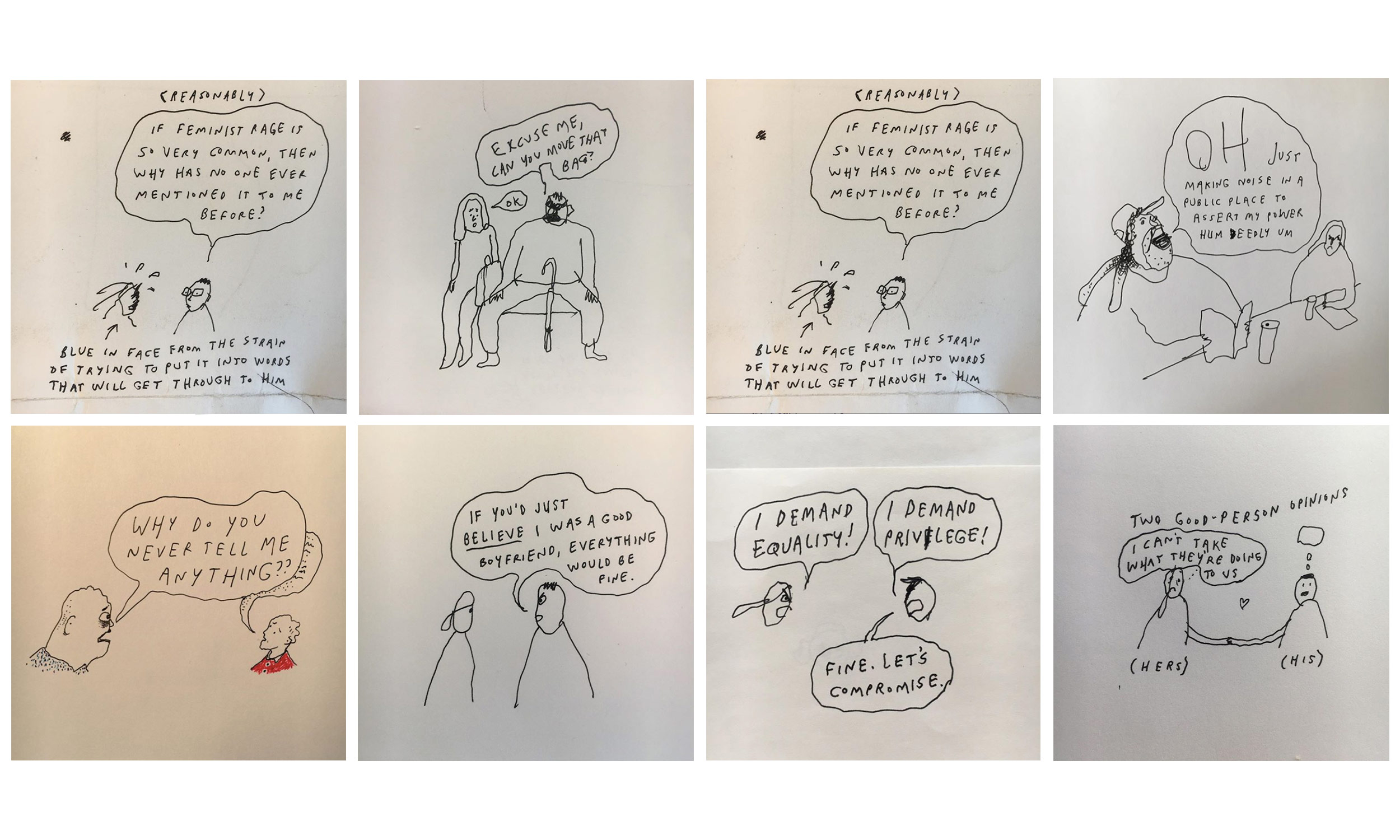

Clara—Do you believe masculinity can be toxic? If so, how?

Liana Finck—I believe treating humans as “women”—in other words, as people whose only job is to be pleasant and nurturing—can be toxic. Men do it; women do it, too.

Clara—How does your work deconstruct this understanding — if you feel it does?

Liana—I did write a chapter of my graphic memoir about my dad—how it was hard for him to admit his vulnerabilities to himself or others because so many people relied on him. I think the patriarchy often forces men to hide their weakness, the same way it forces women to hide their strength.

Clara—Do you see interpretations of masculinity shifting in your industry as interpretations of femininity and queerness evolve?

Liana—I do think it’s a hard time to be a “straight cis white” man. Women and other persecuted groups are asserting their needs these days, and the job of “straight cis white” men is to listen contritely. There’s a lot of shame going around. On the other hand, it must be nice to have brain space for any type of self-expression that isn’t about identity and anger.

Clara—What comes to mind when you think of masculinity?

Rashaad Newsome—A product of patriarchy that blocks people from rich forms of intimacy and perpetuates an irrational loss of their patriarchal place in society.

Clara—Do you believe masculinity can be toxic? If so, how?

Rashaad—In an imperialist, white supremacist, capitalist, patriarchy I don’t really see how masculinity can ever be positive. Its very core is rooted in the divide of “genders.” This divide supports patriarchal ideals, which breads homophobia, white supremacy, imperialism, and capitalism, which are all structures we need to work on freeing ourselves from.

Clara—How does your work engage with traditionally defined masculinity—strength, stoicism, perhaps violence?

Rashaad—I don’t think that “traditionally defined masculinity” is strong or stoic but it can be quite violent. I think my work engages with it by using images from popular culture that participate in “traditionally defined masculinity,” which traffics in the culture of domination. Through composition and juxtaposition, I try to create abstract images that interrogate masculinity and all of its cohorts that collaborate in the creation of systems of oppression that affect all people.

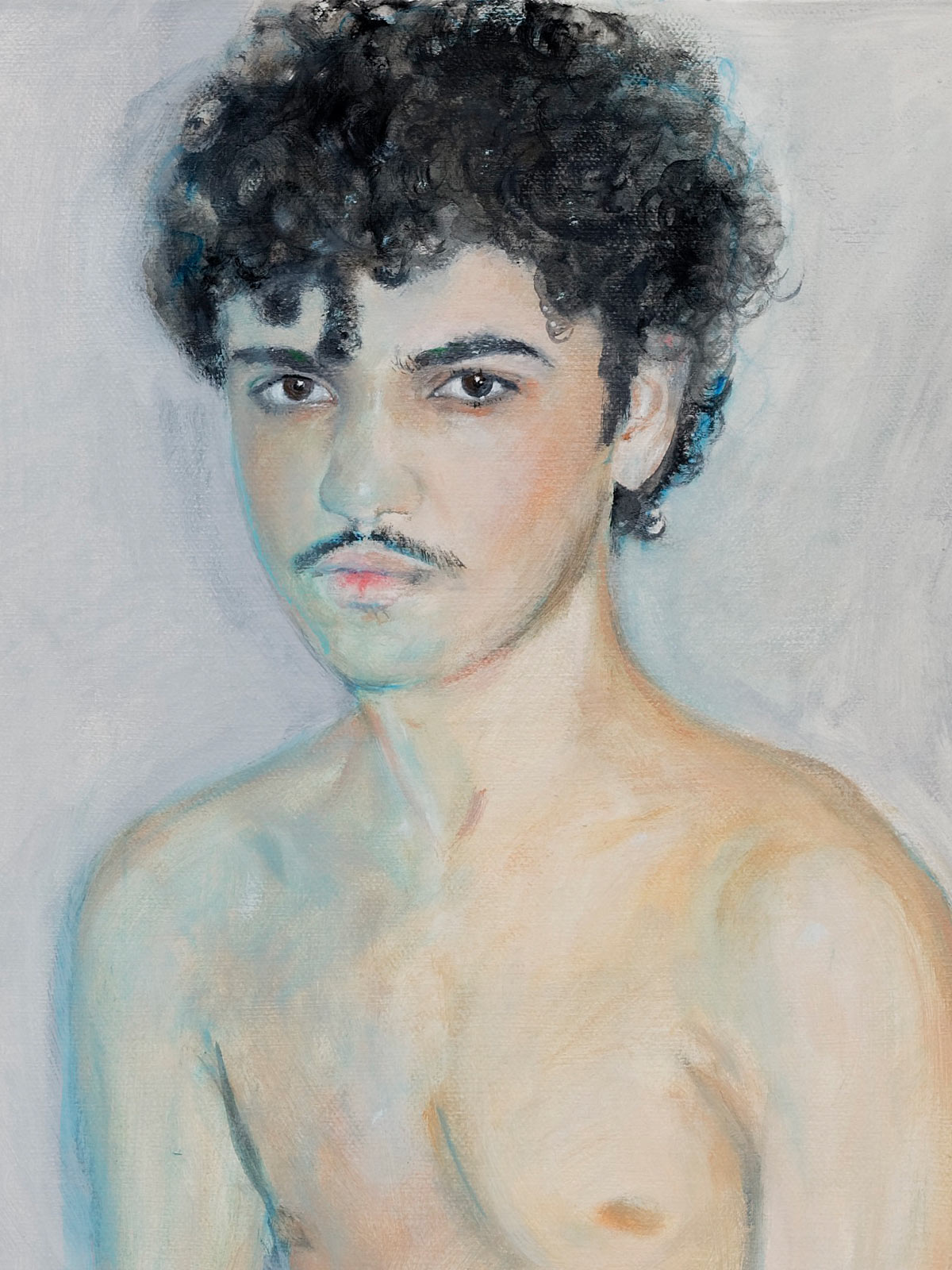

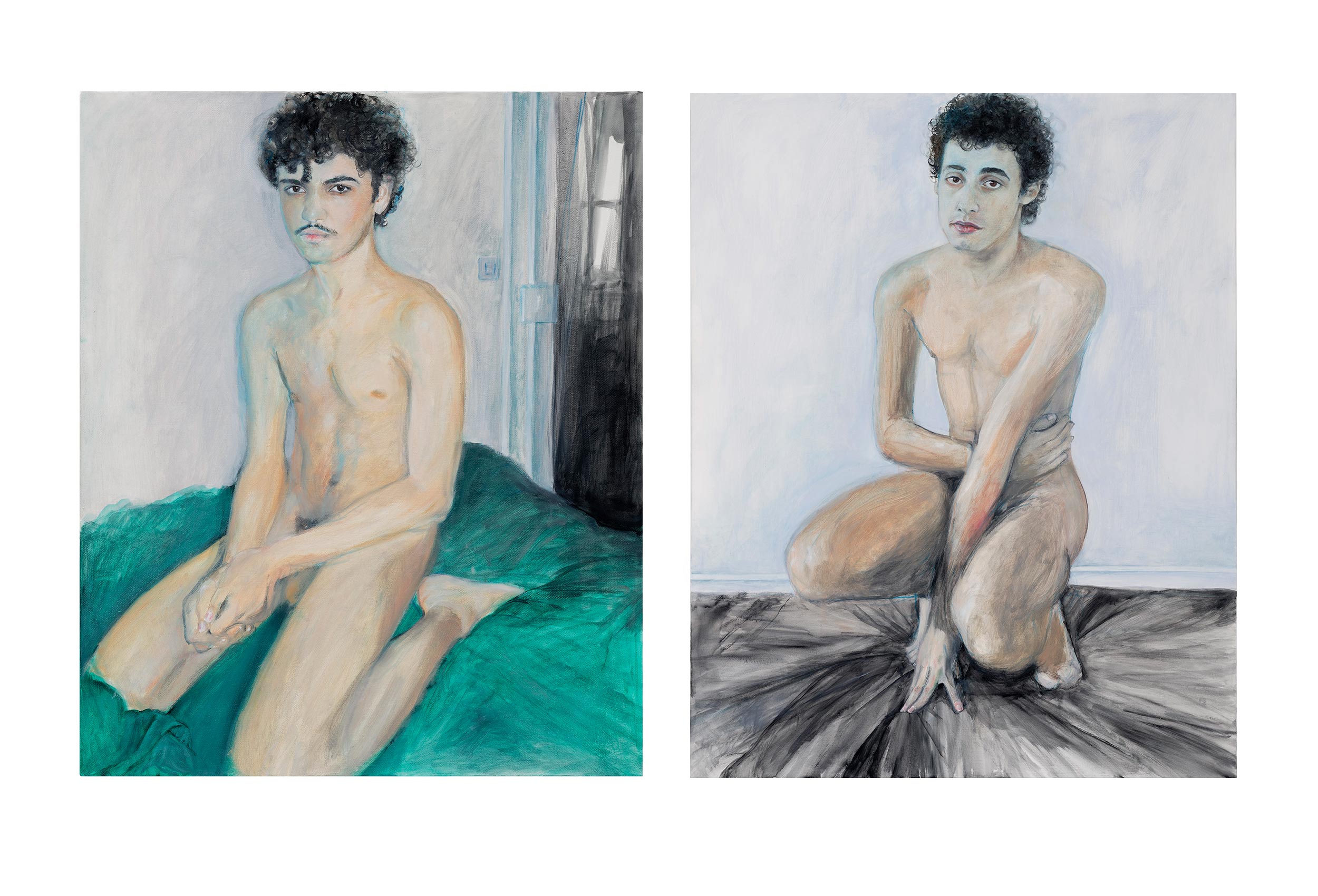

Clara—What comes to mind when you think of masculinity?

Cédric Rivrain—I think of a received idea: a historical and social construction. One can never think enough that Simone de Beauvoir’s sentence, so often quoted and commented on, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman”, implies its masculine corollary and supposes that the man also results from this construction.

Clara—How does your work engage with traditionally defined masculinity—strength, stoicism, perhaps violence?

Cédric—I am interested to circumvent it, to propose variations. Most of my models question themselves, in their life, these gendered partitions. I feel close to them, so I paint them very naturally. If I have occasionally portrayed men whose image corresponds a priori to the traditional idea of masculinity, it has always been by cracking this image, being primarily attentive to their emotion. This trouble is anyway already induced by my gaze on them, my painter gesture inseparable from my queer sensibility. It seems to me that in my portraits the qualities that we generally lend to the masculine, the ones you quote, for example, are rather assumed by women and vice versa.

Clara—How does your work deconstruct this understanding — if you feel it does?

Cédric—The men I draw, whom I paint, whether they are posing friends or figures I invent, always expose the most sensitive, fragile, certain would say feminine part, of masculinity. They can be crying, or on the verge of tears or having a vague look. The bodies, when they are naked, are not sexualized and especially not in a search of power or hardness but rather of abandonment to oneself, to the other, a form of absence which is never associated spontaneously with manliness. During my last personal exhibition in Paris, some portraits of nudes were visible from the street through the windows. It was very interesting to see the reactions of people, mostly men, of all ages. They were rather violent reactions, hostile or shocked, precisely because these men were not used to seeing male bodies naked, sensual without being sexual, represented with softness, tenderness and emotion. I believe that this is at the heart of the problem: dissident, marginal masculinities, are not sufficiently represented in the public space.

Clara—What comes to mind when you think of masculinity?

Gianni Lee—When I think of masculinity, I think of the crossroads of expression and being. It’s far beyond the characteristics of men that define masculinity. It’s more so a language that we all speak; with any language, you have good words and bad words.

Clara—Do you believe masculinity can be toxic? If so, how?

Gianni—Australian sociologist Raewyn Connell did a study on hegemonic masculinity where she argues it’s use of “toxic” practices, such as physical violence, which may serve to reinforce men’s dominance over women in Western societies.

As with all “dominant” ideals, the one practicing will always experience a sort of privilege. Being a man, I’ve experienced that privilege. I may refuse to see the errors in my thinking because of my privilege and upbringing. Of course, through my study of art, I have learned and shed some walls that the toxic parts of masculinity has built up over the years.

Clara—Do you see interpretations of masculinity shifting in your industry as interpretations of femininity and queerness evolve?

Gianni—As interpretations of femininity and queerness evolve, I feel as a heterosexual male I am becoming an endangered species. While I support interpretations of masculinity shifting, I am a strong believer in some traditional forms of masculinity. I feel all variables should be explored to create a more well rounded multi-dimensional man rather than killing off everything in favor of the new ideals. Social media has a way of sensationalizing this new form of man without actually showing people that they have options in manhood. In other words I find nothing wrong with rough housing , brotherhood, tough love ,sporting institutions and other classic structuring of manhood.

Clara—What comes to mind when you think of masculinity?

Amber Vittoria—Ideally, masculinity and femininity live in a balance within all of us; masculinity should be defined differently on a person-to-person basis, as the combination of our individual traits are distinctive. My masculine elements are honest reflection of my actions and strength in my range of emotions.

Clara—How does your work engage with traditionally defined masculinity—strength, stoicism, perhaps violence?

Amber—My work focuses on the idea of femininity and breaking down its societal tropes. The aim with my work is to reveal how femininity and masculinity live in harmony and to dismantle the stereotypes associated with femininity.

Clara—How does your work deconstruct this understanding — if you feel it does?

Amber—By leveraging physical traits such as body hair, overtly extended limbs, and rounded features, my pieces allow the viewer to define what is feminine within themselves.

Related: 5 Photographers on how masculinity informs their practice