Psychiatrists delve into the elusive science behind the 'art attack.'

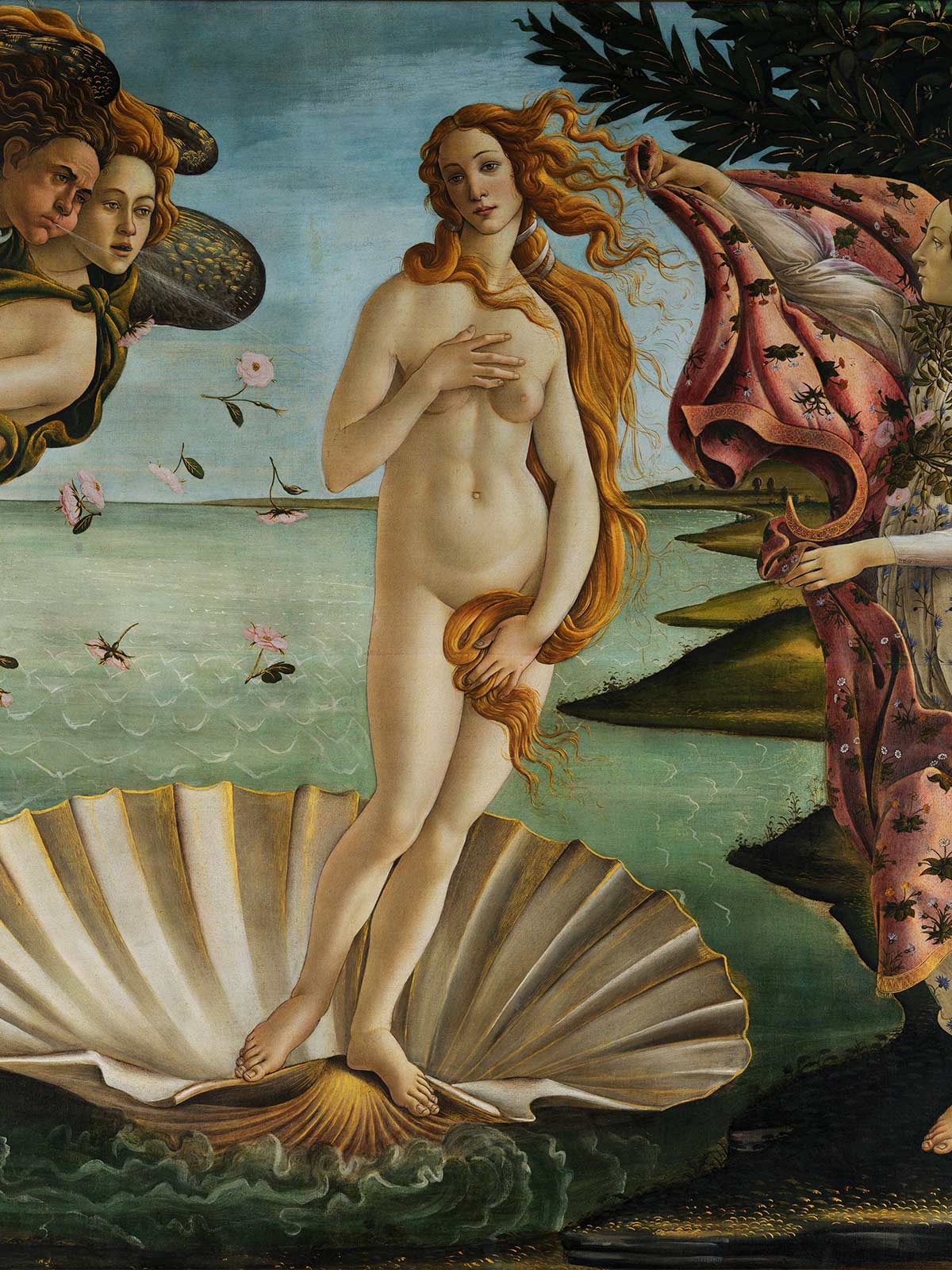

In December 2018, a man suffered a heart attack while looking at Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. Headlines were quick to claim it as another case of Stendhal syndrome—a disorder, specific to Florence, whereby museumgoers are so overwhelmed by the sublime nature of the Renaissance art on display in the Tuscan city that they suffer a panic attack, pass out, or experience a psychotic episode.

It’s a concept that fascinates both physiatrists and artists alike. Director Dario Argento said he experienced a form of it when he visited the Parthenon in Athens as a child—informing his 1996 film The Stendhal Syndrome. But, despite the media meltdown, experts are hesitant to cite the recent case as a classic example of Stendhal. “It seems the person in question had some kind of cardiac event, and he was a local,” says Dr Iain Bamforth, a doctor and cultural writer, “so that rules out Stendhal’s syndrome by definition.”

“We all know the expression, ‘It was so beautiful it took my breath away!’ That common idiom suggests some kind of connection between beauty and the sublime, and an underlying physiological response to emotion,” says Bamforth. “And, indeed, there’s some neurological evidence that the same cerebral areas implicated in emotional reactions are activated by exposure to art or music. But MRIs don’t really explain very much.”

Stendhal is the name of a mid-18th century French writer who described being “seized with a fierce palpitation of the heart” at the doorsteps of the Basilica of Santa Croce. The term was coined in 1977 by Italian psychiatrist Graziella Magherini at the Santa Maria Nuova hospital in Florence, after she published a book on over 100 case studies who had visited the hospital in the past decade with dizzy spells, palpitations, hallucinations, disorientation, loss of identity, and physical exhaustion. Pinpointing a trifecta of causes—“an impressionable personality, the stress of travel and the encounter with a city like Florence”—Magherini said the only treatment was for sufferers to leave the city and return to their normal lives, leaving whatever overwhelmed them behind.

Stendhal remains a mystery, and the science community is keen to crack it. In 2009, a group of Italian researchers trying to find a solid scientific reason for the condition found that certain areas of the brain were activated by observing an artwork, but couldn’t find a clear-cut reason why art, in particular, can cause extreme metal distress.

Clinical Senior Lecturer at the Institute of Psychiatry Psychology & Neuroscience (IoPPN), King’s College London, Dr Timothy Nicholson, thinks the reason some people experience such a visceral response to certains artworks is because of the special significance we attach to them. “We’re only really used to seeing negative things as overwhelming the mind or body,” he tells me. “What we’re not used to seeing is something that is essentially a positive experience, of going to see the art you’ve loved all your life, essentially trigger mental illness or a relapse.”

In 2009, Dr Nicholson and his team treated a case of Stendhal syndrome: an elderly artist who developed a transient paranoid psychosis during a cultural tour of Florence. The first signs of the syndrome appeared when this patient visited the Ponte Vecchio—the oldest bridge in Florence and one of the hallmarks of the city. Describing visiting the art as “like seeing old friends,” the man had a panic attack on the bridge before experiencing persecutory thoughts, such as being followed by the airlines and thinking his hotel room was bugged. The symptoms slowly dissipated over the course of three weeks, but four years later, while travelling to the South of France, he had a small relapse. According to a report published in the British Medical Journal, the man made the pilgrimage eight years before being referred to Nicholson’s team at the age of 72.

Both Bamforth and Nicholson seem agree that it takes a particular set of circumstances for Stendhal to happen. “There are symptomatic aspects of the condition which suggest a common psychosomatic pattern,” Bamforth says. “Travel, disrupted sleep and fatigue, high expectations, and a certain emotional excitement or lability.”

Travel seems to be one of the primary factors, which is why the recent case of a local resident collapsing is suspiciously un-Stendhal-like. But Stendhal is not the only condition where a place or site can overwhelm you. There’s Jerusalem syndrome, where people experience a religious intensity when visiting the Holy City, or Paris Syndrome, said to be most common among Japanese tourists who visit the City of Love only to find it doesn’t meet their dizzying expectations. Symptoms include anxiety, delusion, and depersonalization. “You can clearly see it’s part of a broader group of conditions,” Nicholson tells me. “That is, anything of massive personal significance.” He says there are many other terms to describe a similar sense of emotional overload. “You’ll have seen people have other words for it. Hyperkulturema is a play on the high levels of blood. It’s too much culture in your blood; it’s an ‘art attack.’ You’re seeing people use it as in a heart attack.”

At a time where you can see a near pixel-perfect replica of most of the world’s greatest artworks online, Nicholson is quick to stress that Stendhal isn’t about merely witnessing the work—it’s all about the context that you see it in. I ask him if he thinks someone could suffer Stendhal syndrome by just looking at a piece of work online. “I can’t imagine it,” he responds. “Or if they did they’d have to be particularly susceptible to it. I think, more than the actual art itself, it’s the context; it’s the pilgrimage to go and see it, it’s being in a group, it’s going somewhere you’ve wanted to visit all of your life and that build-up just amplifies everything.”

In 2016, two million people passed through the Uffizi gallery—making it the most visited art museums in Italy. Speaking to the Italian newspaper Corriere Della Sera, just after news broke of December’s incident, the Uffizi’s director, Eike Schmidt, seemed unfazed by the impact the work housed in his gallery had on impressionable audiences. “I am not a doctor,” he told the paper. “I do not propose a diagnosis but I know that facing a museum like ours, so full of absolute masterpieces, certainly constitutes a possible source of emotional, psychological, and even physical stress for the effort of the visit.”

Bamforth agrees that art has a heavy heritage of evoking emotional reactions but it rarely comes down to pure aesthetics. “There’s a long history of people getting very emotional about art, and it doesn’t have to be beautiful. People had to be stretchered out of the first Dada manifestations at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich,” he explains. “The early modernists—the Futurists and Dadaists—still believed that art had enough aura to disrupt ordinary onlookers. It hardly mattered if it was beautiful or ugly. What they were offering was ‘the shock of the new; what Stendhal syndrome seems to be about is’“the shock of the old.’”