Looking back at the impact of the anthropologist turned ‘paraconceptual’ art pioneer, who passed away this week at 78.

This week it was announced that Susan Hiller, the artist known for her love of all things esoteric, died aged 78. Hiller’s background in anthropology, and her persistent fascination with the people and systems that govern our experiences, permeated her 40-year career across installation, sound, technology, and media. Spurred by the marginal and underexplored, Hiller honed in on the occult and arcane aspects of life—even coining the term ‘paraconceptual’ in an effort to articulate her obsession with the outer fringes of the human experience. But news of Hiller’s passing will hardly dominate headlines. She was a somewhat cult name despite having a large following of respectable figures; in 2005, the Guardian summed up Hiller’s influence perfectly by calling her the “artists’ artist.”

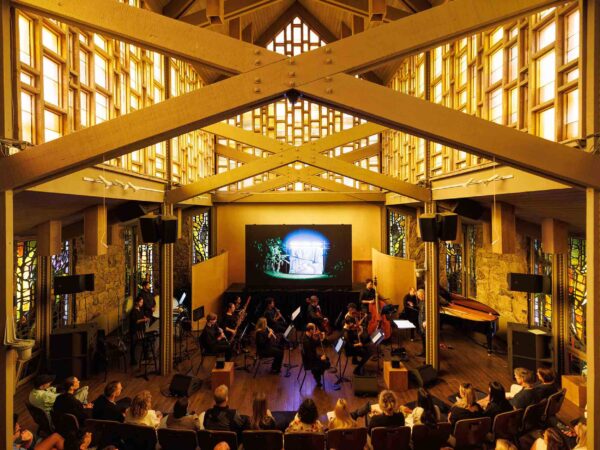

I first came into contact with Hiller’s work during a major retrospective of her work at Tate Britain in 2011. I was an art school student at the time, and it was only my professors that insisted I see the show; outside of the art world, it didn’t garner the coverage an exhibition of that size in one of the world’s most prominent museums should have. That’s because Hiller’s work wasn’t palatable—it was as esoteric as the subjects which fascinated her. Speakers dangling from the sky broadcasted people’s recollections of experiences with UFOs, while fragmented video art documented dying and unspoken languages. Hiller recorded people’s dreams while sleeping in an arc of mushrooms in the middle of a field in the British countryside, and worked with scientists who claimed to have recorded the voices of dead people.

Hiller grew up in Cleveland, Ohio and South Florida in the 40s and 50s, before moving to New York to study film and photography at The Cooper Union, and archaeology and linguistics at Hunter College. She went on to postgraduate work in New Orleans with a National Science Foundation fellowship in anthropology. But she became increasingly uneasy with the level of detachment and impartiality expected of her in this field. Citing anthropology’s “objectification of the contrariness of lived events,” she moved to London in the 60s to pursue art, and called the city home until her death this week.

During her formative years in London, Hiller began blending her anthropological eye with an artistic sentiment. Always attracted to the marginal, she explored everything from the taxonomy of British seaside postcards and domestic wallpaper to dying languages and automatic writing. She was perhaps least sentimental when it came to her own work—once she burned a whole collection of her paintings.

This disrespect for convention is often associated with male artists; your John Cages, Bruce Naumans, and Duchamps. But Hiller carved out space for younger artists to make their own subversive ascent. She was an avant-garde female artist at a time when it was a struggle to be one of those things let alone all of them at once. Working in the largely male-dominated practices of conceptual art and anthropology, Hiller was strong an advocate of women.

“To be a woman and an artist is a privileged position, not a negative one,” she said in Thinking about Art: Conversations with Susan Hiller. “When I speak of being a woman artist, I’m suggesting a position of marginality is privileged. If you are marginal, you know two languages, not just one. And you can translate and bring into language insights that have been previously unarticulated. So I consider, like being a foreigner, being a woman is a great advantage.”

Susan Hiller was a political artist in the truest sense of the word. It’s easy to think of political artists as campaigners trying to shine a light on causes likely to go under the radar. But Hiller wasn’t that. Politics permitted all of her work because for her there were no other lenses in which to view the world. “Artists have a function. We’re part of a conversation,” she once told the art critic Adrian Searl. “It’s our job to represent and mirror back the values of the culture in a way that people haven’t seen before.”