As part of the Document Journal x Prada Mode conversation series at Art Basel in Miami Beach, we highlight six visionary artists changing the future of image making, and transporting us from untenable presents to unimagined futures.

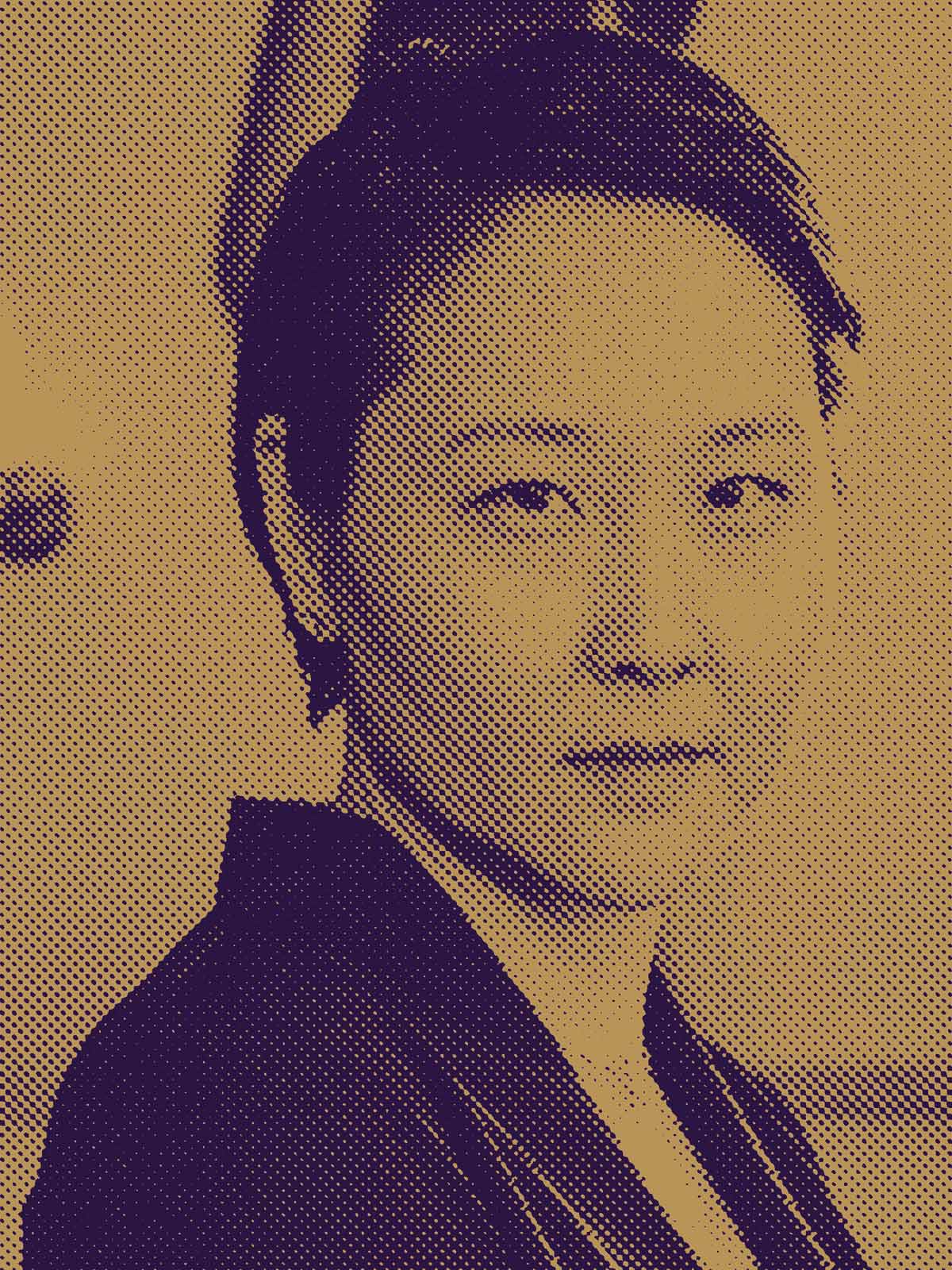

The work of Mina Cheon, a Korean artist based in Baltimore, straddles pop and politics. As the child of a South Korean diplomat who grew up in both the East and the West, Cheon noted the global attitudes towards her divided native country. She eventually used her art practice as a way to educate and make a statement about Korean culture, through a North Korean artist persona named Kim II Soon, and by introducing the western world to Choco Pie, a South Korean treat that is often smuggled to North Korea on the black market. Document spoke to Cheon—a panelist on the talk “Public Access: Offline Media Dissemination” at Prada Mode at the Freehand Miami Beach on December 6—about her practice, her visit to North Korea in 2004, and media dissemination in North Korea.

Ann Binlot—Describe your practice to someone who may not be familiar with your work.

Mina Cheon—I am a global Korean-American new media artist, scholar, and educator who is a professor at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). I make art known as ‘Polipop’—short for political pop art. Polipop combines popular culture with political issues, or pop art and protest, or simply think Andy Warhol and Kim Jong-un.

Ann—Tell me about Kim Il Soon. Who is she? Why did you create her?

Mina—I practice and make art as both South Korean Mina Cheon and North Korean Kim Il Soon, my art persona, [to represent] my native country being divided for 70 years, although the Korean people have been together for 5,000 years. Kim Il Soon is a social realist painter, naval commander, farmer, mother of two, married to the state, and a human being. She is also a cosmopolitan North Korean and knows how to paint abstraction in her dreams, and through her unconscious state is the mother (UMMA) of unification.

Above The Fold

Escapism Revived: Backstage London Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Ludovic de Saint Sernin Debuts Eponymous Collection in Paris

Falls the Shadow: Maria Grazia Chiuri Designs for Works & Process

Introducing: Jahnkoy, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Ann—What prompted your interest in North Korea?

Mina—My interest in North Korea became of focus especially when identity politics and postcolonial rhetoric dominated the academic world, which may have been an academic and intellectual compass for me, but [this interest] is without denial [of my] being a part of the trans-historic, transgenerational trauma of Korean history.

Ann—What was it like when you visited North Korea in 2004?

Mina—I remember being bused through the DMZ into North Korea with large glass windows without curtains so that the North Koreans can see us through the windows; the feeling of being monitored was intense, all our lenses and equipments were checked, we all had to wear badges of occupation, mine being “housewife.” But the moment I crossed into North Korea, the landscape changed drastically. There was something very artificial about the North Korean experience at the same time, the sky seemed more blue, the landscape more natural, and while knowing that it can be due to lack of industrial and technological development, most of the experience was shaped by the heightened program of surveillance and the rigid tourist programming, such as designated time for walking, seeing, eating etcetera. When interacting with North Koreans, however, they were just as Korean as those you see everyday in South Korea.

Ann—Can you briefly explain why media dissemination is so difficult in North Korea?

Mina—There is a lot of media dissemination in the undergrounds of Korea through the black market, but foreign media is not state sanctioned; instead the government has their own media players and propaganda media that is distributed widely, and the propaganda is plastered everywhere in North Korea from posters, banners, statues, to stamps and literature engraved in stones honoring the legends of the Dear Leaders.

Ann—How does the lack of internet access affect North Koreans?

Mina—There is Intranet in North Korea, meaning internal internet, and it is not provided to everyone. Certainly, even in a socialist state, North Korea is highly classist and Pyongyang life is very different than [that of] the smaller towns and villages. I’m not sure if having internet means there is democracy, but freedom of information certainly helps not only with cultural deviation as well as all forms of cultural freedom.

Ann—You’ve also sent contemporary art lessons to North Korea in the form of short films on USB drives. Why do you think this is important?

Mina— They showcase over 40 artists’ works, including Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol, Ai Weiwei, Shirin Neshat, Sooja Kim, Mark Bradford, and more. The tightly edited video includes myself as Professor Kim [Il Soon, and/or Umma] giving the lectures with music video-like quality of video and sound; somewhat mimicking children’s educational TV shows. It possibly is the very first [showcase of] contemporary art works going in; the fact that they are being received and watched, and that content is so radically different from soap operas or anything North Koreans have been exposed to, is also important; and lastly, what artists can do to bring change in awareness—and the activism of art—is crucial in today’s world in terms of direct impact and measurable outcomes.

Ann—Tell me about your exhibition Choco·Pie Propaganda at Ethan Cohen New York Gallery and the piece Eat Choco·Pie Together at the Busan Biennale 2018.

Mina—The first form of resistance [against] the North Korean government by the North Koreans may have been in the loving and receiving of Choco·Pies. At the Kaesung Industrial Complex in North Korea, where there was a joint labor force of North and South Koreans, the South Koreans gifted North Koreans Choco·Pies as a token of thanks, and soon after the piece spread like wildfire in the North Korean black market. At the height of South Korean efforts to share Choco·Pie with North Koreans, I had my first solo exhibition on Choco·Pies at the Ethan Cohen Gallery in New York, with 10,000 Choco·Pies installed in a rectangle to reference the other very famous food art piece [that consisted of wrapped candies] by Felix Gonzalez-Torres. The Choco·Pies in New York were to bring awareness to the Americans of the already existing loving exchanges between the two Koreas, and for Americans to learn of North Korean desire. When shown in the recent Busan Biennale 2018, it was in a circular form to signify unity, as well as the healing aspect of eating that comes with the highly interactive food art for the audience to eat.