In his new book ‘Fundamentals,’ the photographer looks to basketball in Chicago to explore social justice while seeking to empower the voices of those marginalized communities.

For Chicago-based artist Adam Jason Cohen, photography is a form of therapy. Cohen uses his camera as a medium of catharsis and a means for raising consciousness—it allows him to listen intentionally to the needs of his community, while also serving to jump-start honest conversations about the social issues affecting its people.

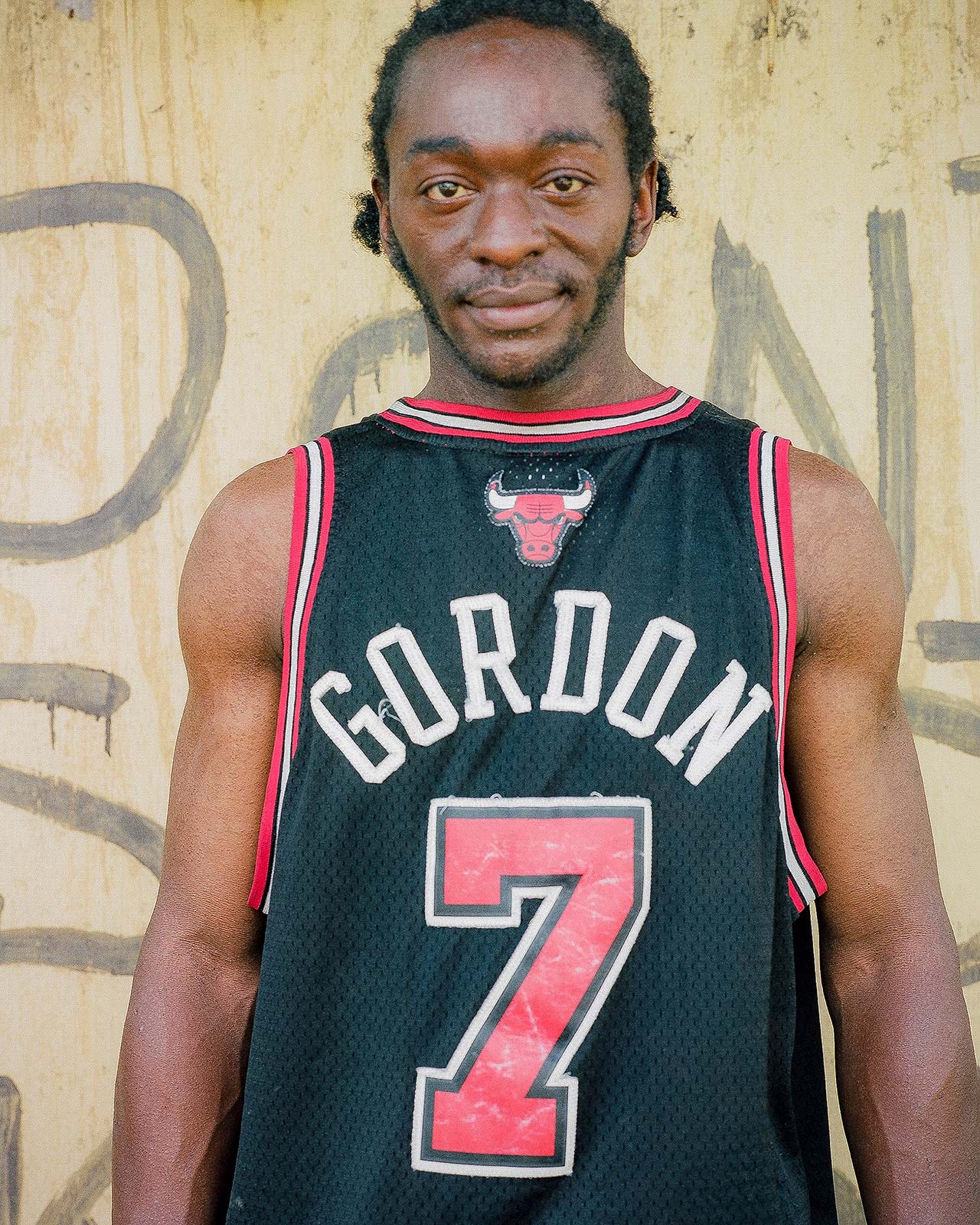

In his new photo book, titled Fundamentals, basketball emerges as a symbol of Chicago’s failure to take care of its youth of color. More than a game or sport, basketball functions as a visual language; a symbol of the pride Chicagoans feel for their metropolis but also of the prejudices prevalent there, which cause public spaces to be neglected and prevent marginalized communities from getting access to necessary resources and educational programs.

Document spoke with Cohen about how he hopes images of basketball culture will inspire the city to address these issues and what his role is in documenting the community.

Sara Radin—Hey Adam, thanks for making time to chat. When did you first start practicing photography and what do you love most about the medium?

Adam Jason Cohen—I didn’t go to a great high school and there weren’t a lot of art resources there. I began taking pictures because there were people around me who were taking pictures. From there I went to school for photography, but I decided it wasn’t for me because I was more interested in doing photography outside of school—having more one-on-one relationships with other photographers, peers, and mentors. After I dropped out of college, I saw Robert Frank’s anniversary of The Americans at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. I was really moved and in that moment I knew that all I wanted to do was to be a photographer.

Sara—What was it about Frank’s work that drew you to photography?

Adam—At the time, his work felt really honest and captured life in the moment. That really spoke to me about shooting more and inspired me to be more aware of my surroundings a bit more. He was always an outsider. He wasn’t from the United States, which gave him an interesting perspective when he was shooting. He treated what he was photographing with a lot of respect and there was a lot of honesty within that respect as well.

Sara—How have you brought that sense of honesty to the work that you make? What kinds of stories do you attempt to show through your own lens?

Adam—I’m not really that great of a photographer. I’m just really good at having organic conversations with people. It’s a normal day-to-day thing for me, walking up to someone and talking to them and listening to people. That’s what I really try to capture in a photograph. Oftentimes I’m not even bringing my camera out into the world. I just get absorbed in the world. I try to talk about social or systemic problems happening around me, and hope that it encourages people to do something about it.

Sara—It’s interesting because I feel really similarly about my work as a writer. It’s not really about writing for me, it’s about storytelling and using my platform to shed a light on the work of other people who are talking about social justice issues in a fresh way. So, when did you start working on the Fundamentals series?

Adam—This series was done over the last four years but I started taking the photos in 2014. In 2016, I made a little zine called Hoop Dreams, which was inspired by a 90s documentary with the same name, because I wanted to start getting some attention on these issues.

Sara—Why did you decide to use basketball as a way to discuss these problems?

Adam—Basketball is ingrained in the nature of Chicago so I used it as a frame of reference because it was a way for me to get a message across about what’s really going on. I also have a real love for the game. I’d play seven times a week if I wasn’t 32 years old right now.

Sara—How was the project received? Why did you choose to do this larger version on your own?

Adam—After I made Hoop Dreams some NBA players and local news organizations ended up coming to me and asked if I wanted some funding. But I was like, ‘Hey, instead of helping me, you could also help the community yourself.’ In the last few months I decided was done shooting this series and I wanted to put all of it out in the world. I wanted to spread the DIY spirit and show that everyone has some sort of responsibility wherever they’re living or whatever community they’re a part of. You know?

Sara—You mentioned on Instagram that the spark that ignited this series was the fact that the kids deserve better. Could you share more about that?

Adam—I think as a whole and as a city we can do better by being better neighbors and making sure our money is staying local in the community. My main responsibility outside of being a storyteller or working with youth is trying my best to be a liaison between huge companies and communities. I teach as many youth programs as I can and most of them are based around storytelling or photography or video. I want to show kids that they can empower themselves just by making images and that that can lead to change. People want to hear their point of view.

Sara—What were some of the moments you captured that you felt represent some of the issues you were trying to talk about?

Adam—I photographed this stuff all over the city. The first portrait I took for this project was because parents urged me to do it. A lot of the details in photographs—even a line painted on the cement says so much to me. It shows how so many parents and older people in these neighborhoods have had to make safe places for the kids because the city won’t provide that for them.

Sara—I like how basketball represents a sense of pride for the city of Chicago, and that you’re using these images to challenge that and show the ways the city is not caring for its people.

Adam—Taking people’s pictures is a very big honor. I mean, I hate getting my picture taken or even hearing my own voice. So the fact that someone is willing to let me into their life, I just try to respect that and make sure I’m not doing a disservice to them. I try to make sure the photos stay as honest as possible.