Lynne Tillman and other contributors to Suck magazine look back and analyze the legacy that the transgressive magazine left behind.

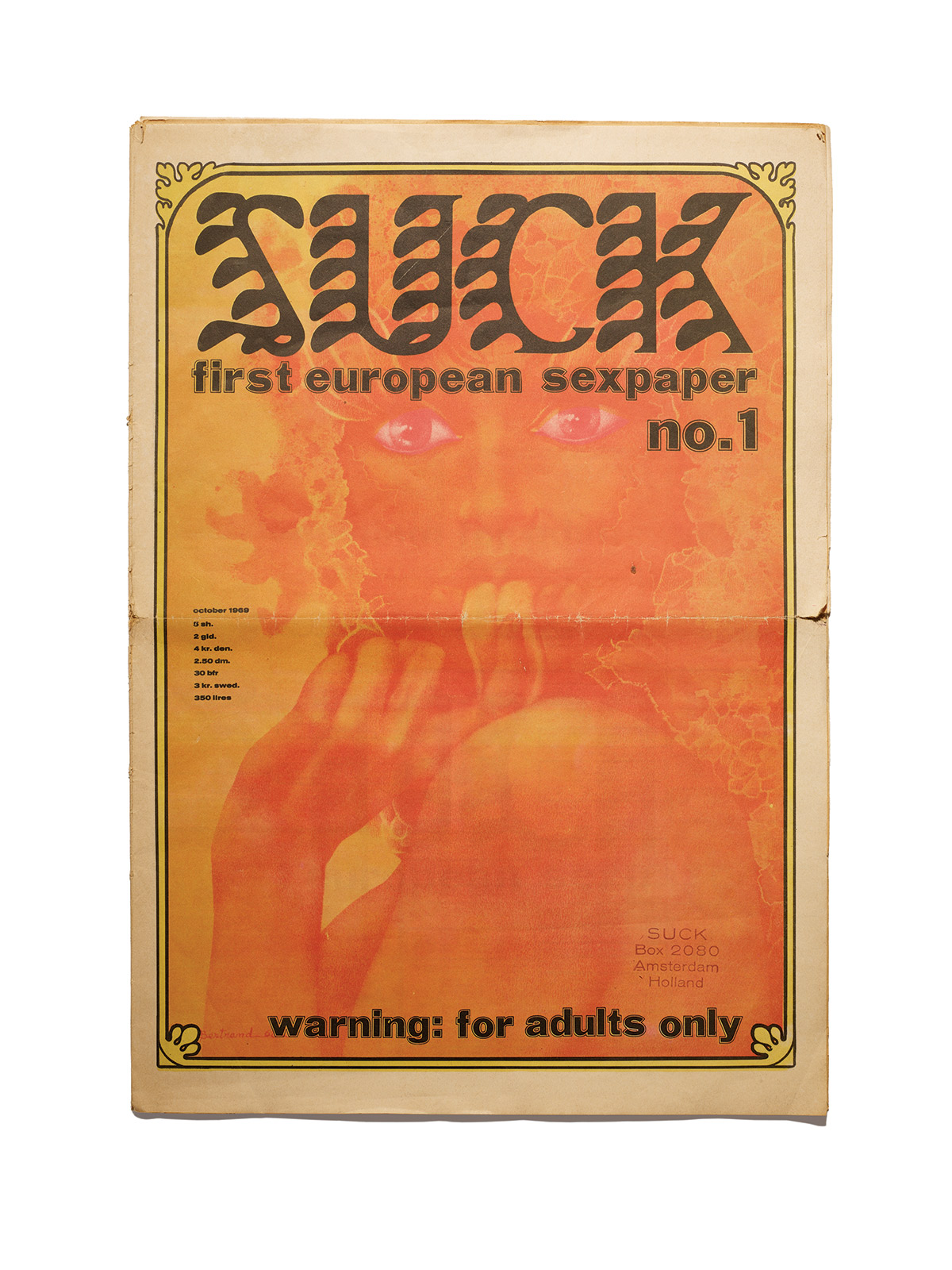

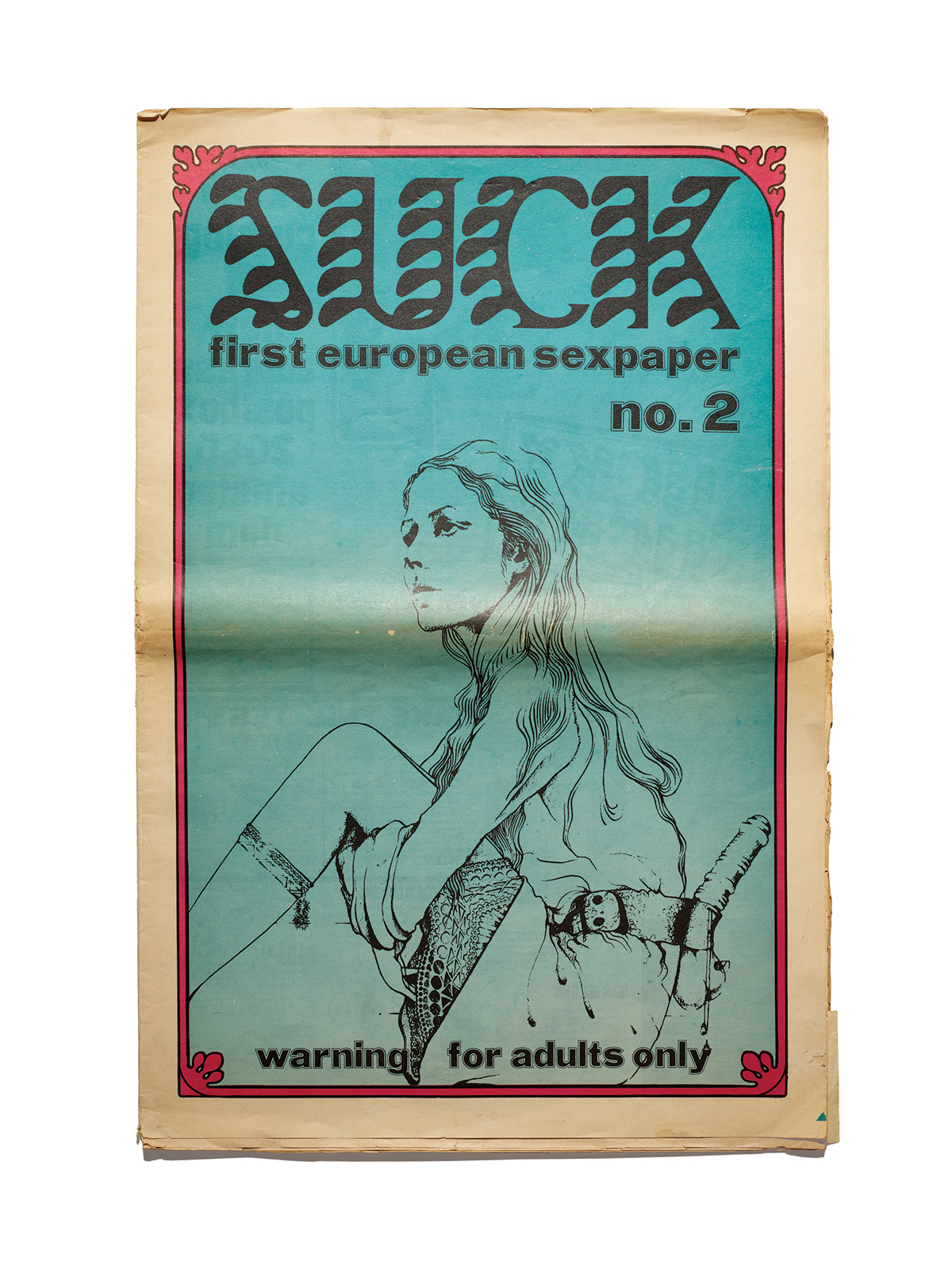

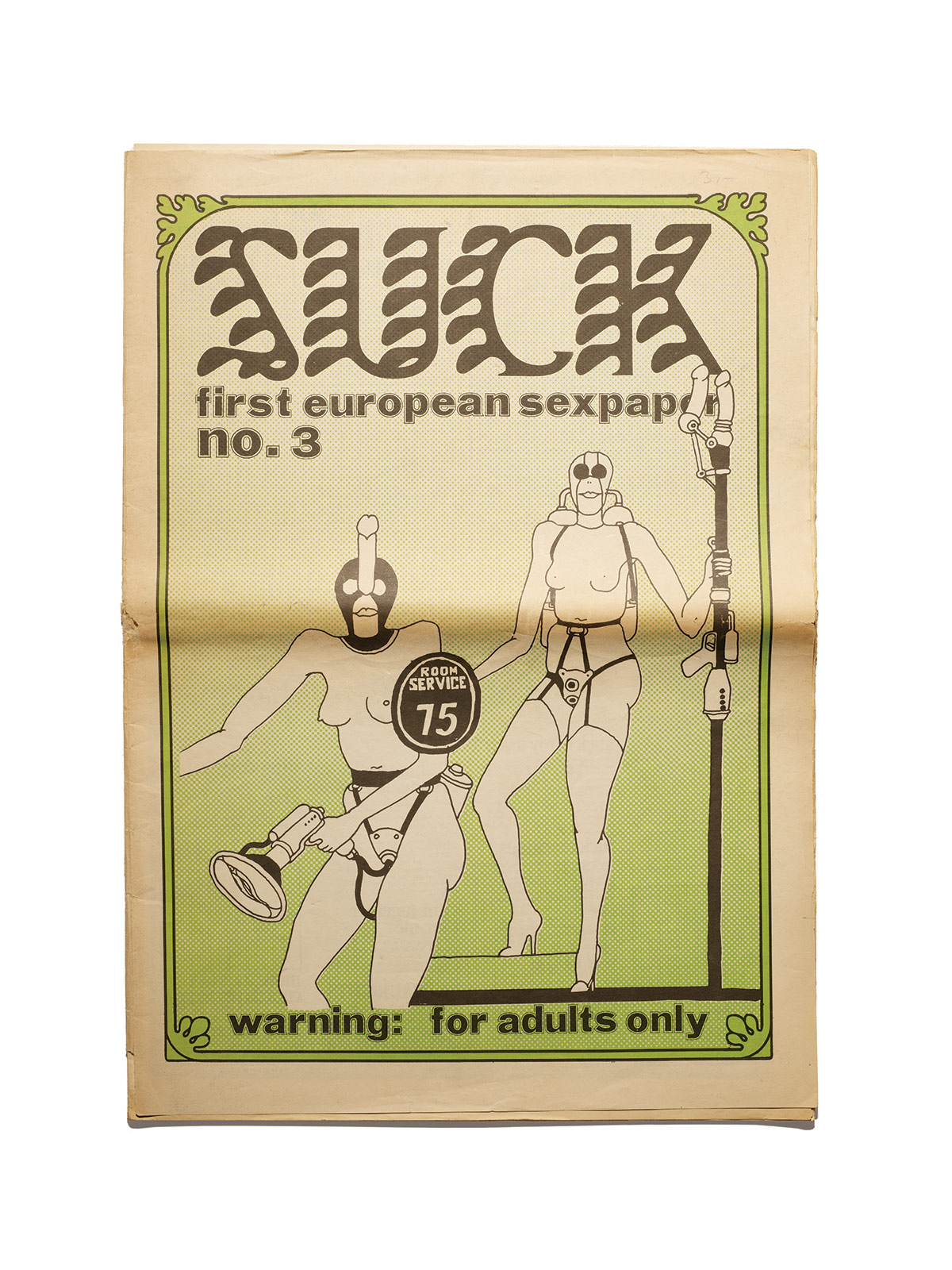

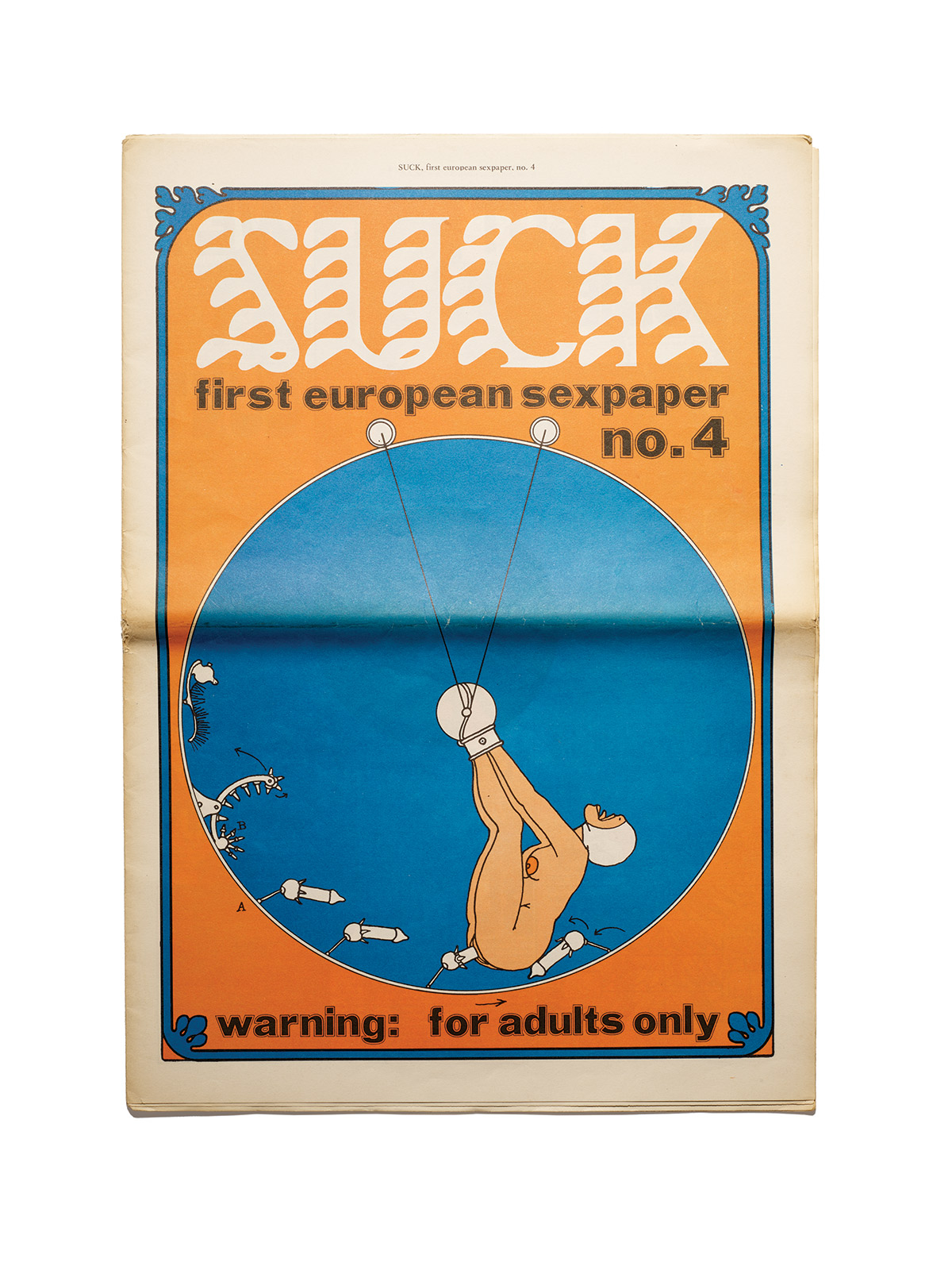

There were “men’s magazines,” and then there was Suck, an experimental amalgam of sexual liberation, feminist ferment, alternative visual culture, and literary ambition, translated into eight crazy issues of newsprint. Founded in London in 1969 and published irregularly until 1974, Suck offered a radically different vision of avant-pornography—no small feat in an era that produced a plethora of explicit and transgressive printed matter. The self-styled “European sexpaper,” Suck decisively contested the formulaic conventions of straight porn mags.

With Germaine Greer as one of its star ambassadors, Suck blurred many boundaries in an attempt to forge, as Greer told the academic journal Women’s Studies International Forum, “a new kind of erotic art, away from the tits ’n’ ass and the peep-show syndrome.” Suck was premised on the notion that explicit erotica was more than just physically arousing—it could also be political and intellectual, and it didn’t have to be inherently exploitative. As writer Chris Kraus argued in a 2008 piece for Artforum about the cultural significance of Suck, the alt-porno demonstrated that “sexuality and daily life were seen as the locus of politics” and that “the public exposure of traditionally private behavior was a means of disrupting the social order.”

“The real provocativeness and importance of endeavors like Suck,” Kraus continued, was that the magazine “not only demystified the sex acts themselves but undermined any mythologizing of the individual speakers…. Suck’s authors viewed disclosure not as personal narcissism but as a means of escaping the limits of ‘self.’”

Unlike run-of-the-mill “jerk-off” magazines, Suck boasted some sky-high (if erotic) culture, such as W.H. Auden’s little-known “The Gobble Poem,” which pruriently detailed the poet’s lusty affair with a male lover, and a translated excerpt of Guillaume Apollinaire’s X-rated novel The Debauched Hospodar. Through the quality of its writing and accompanying visuals, Suck put its anarcho-intelligentsia stamp on prosaic magazine fodder with eroticized horoscopes, interactive features (the “Feminine Fuckablity Test” of Suck No. 1 was followed by the male version in the second issue), celebrity testimonials, (porn) film reviews, and personal ads. Names were named and boundaries were pushed: Actress Jean Stapleton confessed her first oral sex orgasm, accompanied by an exquisite line drawing that appears to be something out of a smutty fairy tale; Beat poet Michael McClure offered a confessional “Fuck Essay”; Earth Rose (Greer’s Suck alter ego) dropped sexual gossip about London’s A-list underground scenesters; and John Giorno titillated with a short excerpt from his poem “My Old Men” that listed the endowments of notable artists: “The size of their cocks hard: Jasper Johns 7 inches, Biron Gysin 5 inches, Andy Warhol 4 1⁄2 inches, William Burroughs 3 1⁄2 inches.” There were no half measures on the pages of Suck—art, sex, and life were collapsed and then absorbed into the totalizing experiment.

To fully grasp the radical legacy of Suck, a succinct detour into the so-called “Golden Age of Porn” is required to provide context. The sex press was largely an underground phenomenon in the US and much of western Europe until the mid 1960s, when a string of court cases gradually redefined obscenity laws and weakened government censorship. By the late 1960s, Suck was one of many titles—among them, such sex-heavy icons of the countercultural press as Oz, Actuel, Yellow Dog, and Other Scenes—that constituted a dam burst of mass-culture porn.

Pre-Suck, Hugh Hefner set the publishing standards for the genre in a relatively soft and decidedly urbane tone, launching his tasteful “centerfold” paradigm in the glossy monthly Playboy in 1953. Under the tagline “Entertainment for Men,” Playboy fashioned an editorial recipe that combined lusty (semi-) nudes with a relatively highbrow potpourri of textual content, including in-depth celebrity interviews and essays on politics, culture, and literature. Given the contributions of such luminaries as Vladimir Nabokov, Jack Kerouac, Roald Dahl, and Norman Mailer, reading Playboy “for the articles” became the perfect alibi for libidinous male subscribers.

The general blueprint established by Playboy served the emergent skin-magazine business, though as the 1960s wore on, new titles veered increasingly into less tasteful, more explicit, and in some instances vociferously incorrect territory. Riding on the coattails of the sexual revolution, these hardcore magazines catered exclusively to heterosexual male readers. A new cadre of pornographer-entrepreneur-auteurs tweaked Hef ’s formula to reach different target audiences. On a mission to poach the readership of Playboy, Bob Guccione launched Penthouse in 1965. Guccione targeted the upscale, aspirational demographic with a similar “sex, politics, and protest” editorial mix, while upping the ante with full-frontal nudity, more provocative poses, and his own, signature soft-focus photographic style.

Three years later, Al Goldstein infused his hardcore tabloid Screw with a heavy dose of shock-and-raw obscenity, promising in the first issue “to never to ink out a pubic hair or chalk out an organ. We will apologize for nothing. We will uncover the entire world of sex. We will be the Consumer Reports of sex.” If Goldstein strove to marry the era’s revolutionary ethos with prurient smut, he often did it under the sly cover of cutting-edge visuals by such artists as Dan Graham, Andy Warhol, and Yoko Ono.

With Hustler, which debuted in 1974, Larry Flynt swung the pornographic pendulum towards the more sensationalist tastes of the working classes, endowing the magazine with a crass, anti-revolutionary, politically incorrect, and populist slant. Flynt’s editorial agenda was driven in large part by his desire to demean the feminist movement. With the taunt, “We will no longer hang women up like pieces of meat,” the cover of the June 1978 issue poured salt into the wounds of that decade’s “feminist sex wars” by collaging the legs of a naked woman with a meat grinder.

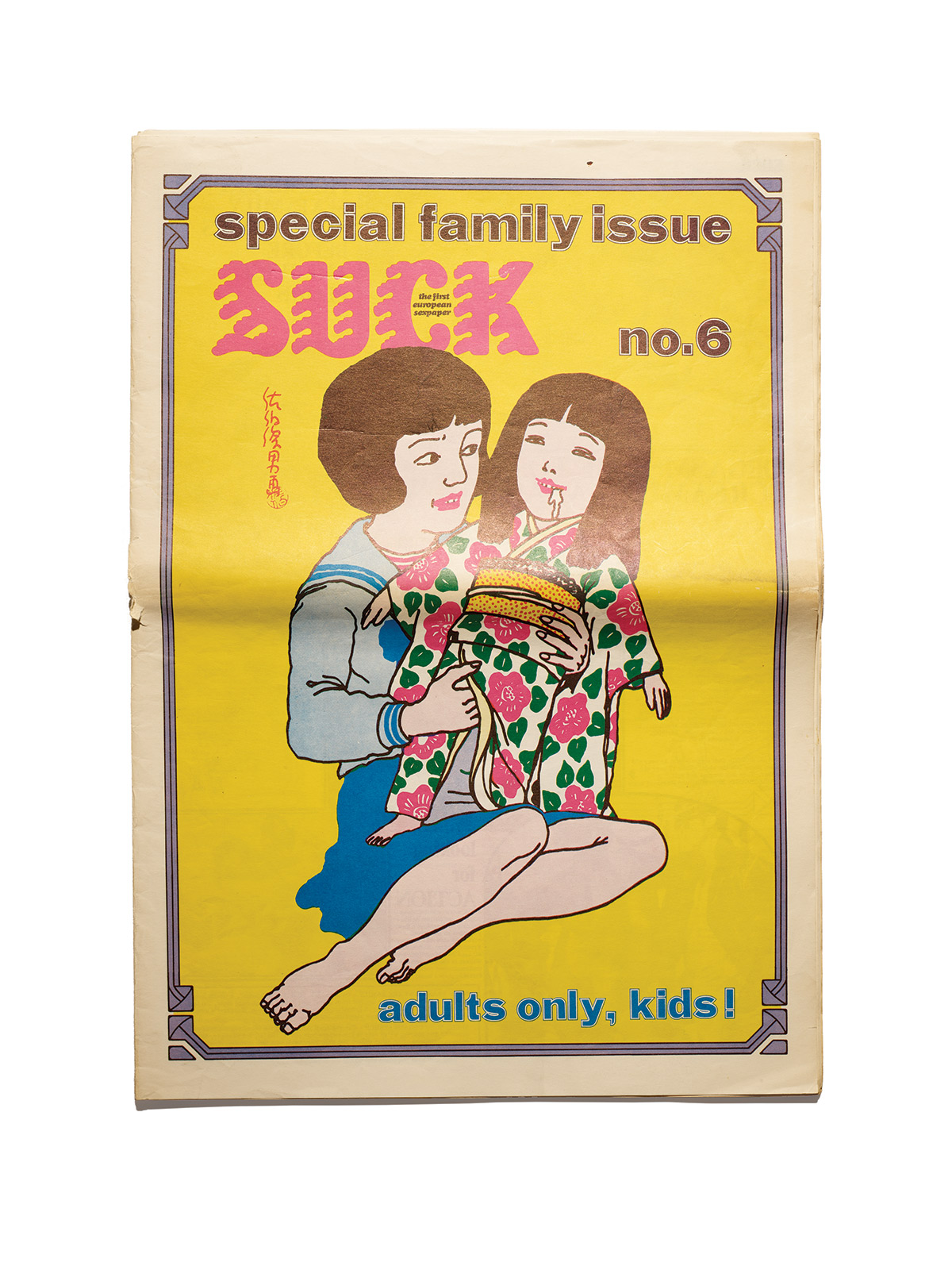

“The iconic hand-drawn covers could have been transposed onto an acid rock album cover, were it not for the dildo in the hippie’s belt or the creepy geisha doll the school girl was fondling.”

Though it was in many respects the antithesis of Hustler and its horny-male cohort, Suck was, in its own way, no less shocking or graphic. Its core mission was to thwart the misogynistic, masculine hegemony of regular porn. Suck actively courted both male and female readers, with full-frontal nudity of both genders, including erections. It refused to privilege heteronormative tastes, and page after page featured polymorphous sexual experimentation. Gay and lesbian pictorials were presented next to straight sex, orgy scenes rubbed up against photos touting masturbation, transgender and cisgender models intersected on its spreads without any fanfare—in a revisionist reading, the mix might be described as “queer.”

Suck embraced feminism. Among the women prominently featured as editors, contributing writers, and photographers were some illustrious and very public feminists. The editors thought of themselves as a “family,” and their collectively run editorial board repudiated the lone male editor-auteur-pornographer model.

These editors wanted Suck to be more than just a magazine—indeed, they aspired to no less than a roving experiment in living and loving, with their own amorous and literary exploits often providing fodder for publication. They also spawned the organization SELF (the Sexual Egalitarian and Libertarian Fraternity), which became the organizing body of the two infamous Wet Dream Film Festivals in Amsterdam, in 1970 and 1971. And they created several spin-off publications, including the erotic photo-novella The Virgin Sperm Dancer, while fostering the careers of such young writers as Lynne Tillman, whose first novella, Weird Fucks, incubated during her years in the Suck family.

While far from a conventional nuclear family, the editors nevertheless found themselves with a father figure in Bill Levy, the former chief editor of London’s countercultural paper International Times (IT) who shaped the editorial direction of Suck. As Tillman explained, “Suck’s primary idea was to join writing, pornography, and sex—to knead it together. It really was equally born of the sexual revolution and out of a desire to change writing. Bill wanted to do something different, something bold.”

To this end, Levy recruited some of his London acquaintances and former collaborators from IT to join him in founding Suck. Levy convinced literary heavyweights William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg to make occasional contributions, while the sexologists Eberhard and Phyllis Kronhausen loomed over the proceedings as unofficial gurus. Other alumni of the IT scene joined, as well, including Greer; the English poet and playwright Heathcote Williams, who was dating the model Jean Shrimpton (a relationship that yielded both sensationalist celebrity fodder and a notorious photo-collage in Suck No. 8 in which Shrimpton is depicted as Williams’s erect member); and Jim Haynes, the founder of the Arts Laboratory in London, who had, according to Tillman, “an address book for every city in the world.” Each of them embodied various camps of the Swinging Sixties ethos.

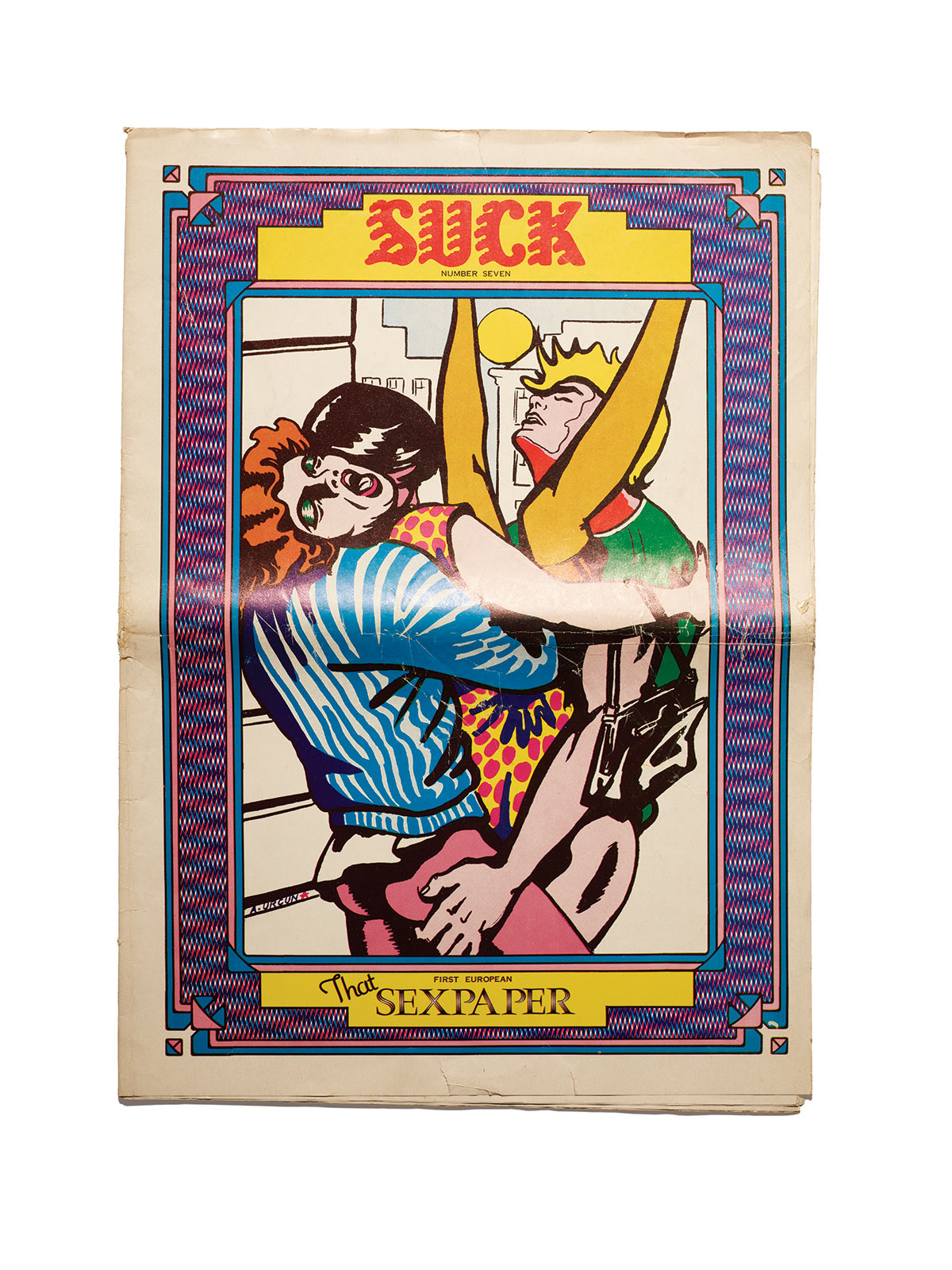

To balance out all the heady textual content, Levy enlisted Dutch artist Willem de Ridder to spearhead the tabloid’s zeitgeisty graphic design and artistic content. A key member of the Fluxus movement, de Ridder tapped his network for contributions from such artists as Giorno, Valerie Solanas, Otto Muehl, Thomas Bayrle, Gunter Rambow, and Ed van der Elsken. Under de Ridder’s direction, the visual identity of Suck embraced the psychedelia that was percolating through pop culture: bubble lettering, op-art graphics, saturated and vibrating color palettes, goofy photo collages, and groovy illustrations. The iconic, hand-drawn covers—whether that of the second issue, which featured a beautiful hippie girl, or the sixth issue, depicting a Japanese school girl—could easily have been transposed onto an acid rock album cover, were it not for the dildo in the hippie’s belt or the creepy geisha doll the school girl was fondling.

De Ridder also provided Suck with a home office in Amsterdam, where it could circumvent the more stringent obscenity laws of the UK. Once the new office was established and running, the Suck kinship circle was completed by Tillman and the Dutch literary writer and translator Susan Janssen (who was known by her moniker “Purple Susan” and who became Levy’s romantic partner and later his wife).

Propelled by the Women’s Liberation Movement and sexual freedom, the women of Suck were what made the magazine absolutely revolutionary. Anna Beeke was a photographer who had come into the Suck orbit through her Fluxus performance work with her fellow Dutchman de Ridder. As a rare woman in an erotic field dominated by men, Beeke frequently contributed groundbreaking, outré images to the earliest issues of Suck, in addition to shooting all the wild pictorials for The Virgin Sperm Dancer under the pseudonym “Ginger Gordon.” One of her most iconic images appears in the first issue, depicting a male odalisque against an orientalist backdrop, wearing an ornate, silver “penis holder.” “I was always interested in making erotic photographs of men,” Beeke said. “Beyond the gay scene, there was hardly any photographer who did!”

When asked about her involvement with Suck and her relationship to feminism, Beeke replied:

Suck’s philosophy was that sex should be totally free, and you should be able to have sex with whoever or whatever if you and the other person(s) wanted it. However, the most important thing for me was that it should never have any commercial aspect. Neither the sex, the writing, [nor] the images. Sex should be fun and for free. Therefore, it had nothing to do with pornography. On the contrary, it was a statement against pornography. If there was more freedom that way, there would be less need for women and men to exploit sex.

The pursuit of sexual freedom without exploitation was one of the core themes espoused by Greer in her numerous contributions to Suck. It was Greer’s fiery presence as an editor that bolstered the magazine’s feminist credentials and gave it an aura of glamourous intellectualism. Shortly after she joined Suck, she published her era-defining book, The Female Eunuch, which skyrocketed her to pop stardom. The majority of her Suck essays could be characterized as putting into practice the theories she had espoused in the book. And while Suck was never intended as a specifically feminist “sex paper,” it is retrospectively astonishing how Greer’s contributions prefigure what became known as “sex-positive” feminism—a minority position that emerged in response to the “sex wars” of the late ’70s and early ’80s and the calls for censorship by such groups as Women Against Pornography. Her self-help-inflected, body-positive essays in Suck bore such titles as “Lady Love Your Cunt,” “Bounce Titty Bounce,” and “Ladies Get on Top for Better Orgasms.”

The women’s empowerment tenor of these pieces was echoed by other Suck headlines as well, such as “Women Need Whore Houses” by Dinah Armstrong (Tillman’s alias) and “Can a Woman Fuck a Man?” Revisionist historians might be tempted to build a monument to Suck as an early beacon of radical feminist erotic triumph. Yet Tillman offers a more sobering (and prosaic) explanation: While feminist politics perfumed the air, the original catalyst for the women-focused content was men’s desires. “It was Bill’s point of view that fucking is better if women were into it,” she said. “I think he did want women to enjoy sex, and I think he wanted to enjoy sex…. He wasn’t misogynistic.”

However self-serving their motivations may have been, Levy and the other male editors nevertheless ceded a great deal of power to Greer. Her first-person voice almost single-handedly articulated the revolutionary ambitions of the group. As the Suck frontwoman, Greer enunciated the magazine’s mission to invent a more “ethical” pornography. In a postmortem article about the first Wet Dream Film Festival, she implored, “Confrontation is political awareness. What we discovered at the Wet Dream Festival is that we will have to generate enough energy in ourselves to create a pornography which will eradicate the traditional porn by sheer erotic power….We must commission films, make films, write, act, cooperate for life’s sake. The battle against sadism and impotence is more desperate than we ever believed.”

Greer flexed her editorial muscles by insisting, as she recalled in her essay collection The Madwoman’s Underclothes, on “using male bodies as often as female, invading the privacy of the editors, naming names in sex news, and developing a new kind of erotic art.” Even before Suck, Greer, who had a Ph.D. from the University of Cambridge, had put her money where her mouth was by writing first-person articles chronicling her sexual conquests under the moniker “Dr. Gee, the only groupie with a Ph.D. in captivity.” In Suck No. 6, she raised the stakes by publishing a text entitled “I Am a Whore,” in which she renounced any special status as an intellectual or feminist. “Whore is a dirty word—so we’ll call everybody a whore and people get uptight; whereas really you’ve got to come out the other way around and make whore a sacred word, like it used to be and it still can be. That’s why I use the word whore. My sisters won’t allow it to be used. But I would prefer to be called a whore than a human being.”

On the heels of publishing this manifesto-like text, Greer submitted a provocative nude photo of herself to the editorial collective for publication, with the understanding that all of the other editors would do the same.

The infamous photo shows Greer in a naked somersault, smiling goofily at the camera, with her hairy vulva and exposed anus at the center of the frame—not exactly the posturing one would expect from a radical feminist. Greer’s “split beaver” shot was run as a cheeky, stand-alone portrait in Suck No. 7.

Speaking with The Guardian about her gesture more than four decades later, Greer explained how the image subverted the objectification of traditional porn. “Face, pubes, and anus framed by vast buttocks—nothing decorative about it. Nothing sexy about it, either. Confrontation was the name of the game. Not so much ‘kiss my arse’ as ‘kiss my arsehole’—a different matter entirely.” While Greer consented to the provocative pose when the photo was taken, a huge row erupted when she learned that her image had been exploited and that the other editors’ nudes had not been published. It was this blow-up that would lead to the dissolution of the Suck family.

“‘I think in a way all of it was the same to [Levy],’ said Tillman. ‘It was what went against middle-class values. Bill was really interested in shocking people.’”

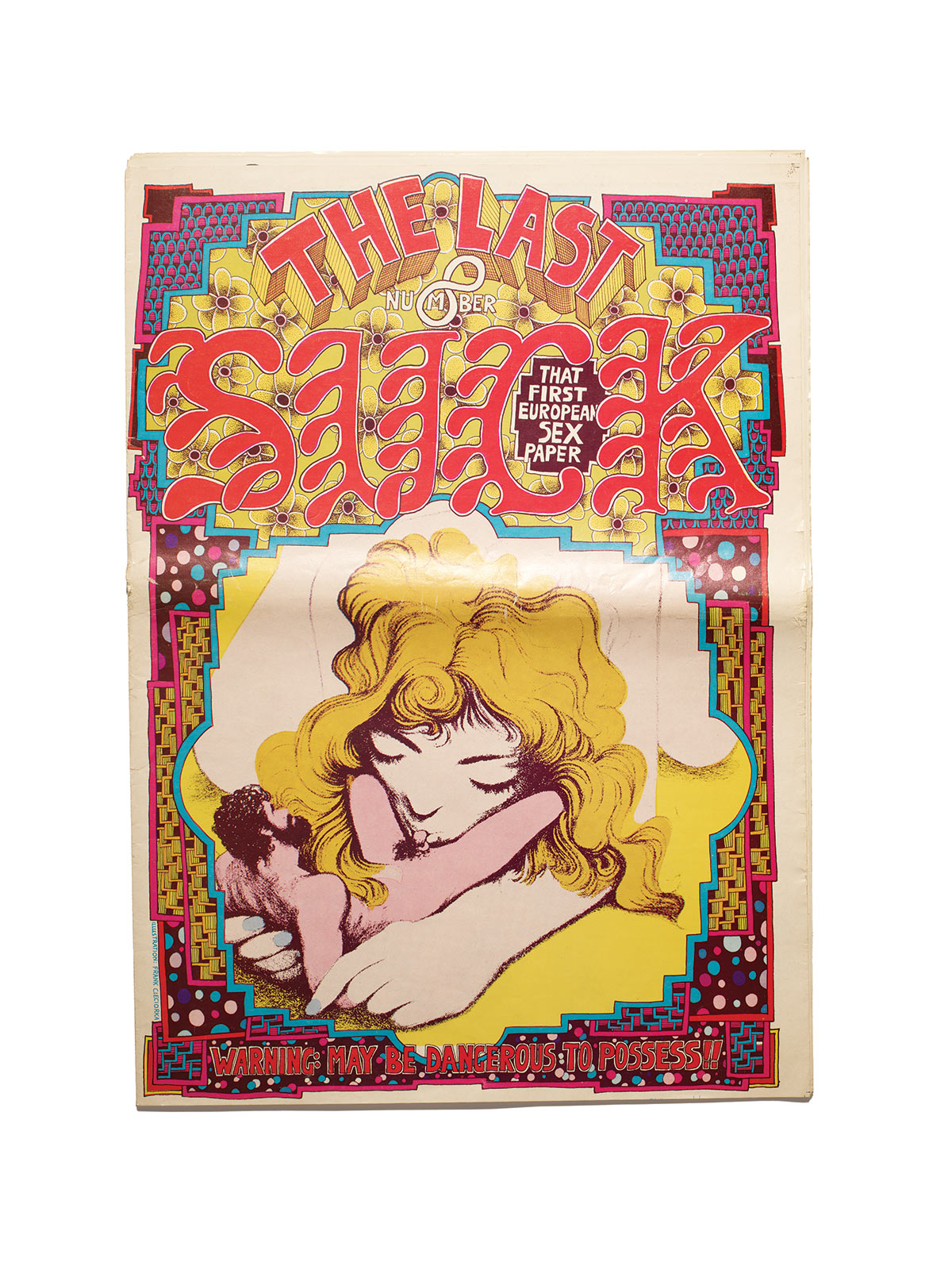

The eighth and final issue of Suck, structured around Greer’s resignation letter, brought an end to the imperfect, inherently doomed enterprise. In the letter, Greer decried her misrepresentation, seething, “My action was never meant to be a piece of exhibitionism on my behalf. It was meant to be a group action on the part of editors of Suck magazine. The fact that it wasn’t is just a further example of the spurious news of your pseudo-revolutionary aims.” Taken out of the collective context, Greer felt the gesture had become “an explosion of the personality cult” and “disgusting to me as a feminist.” Levy published a handwritten response on the page opposite Greer’s letter, in which he implicitly conceded, once and for all, that the magazine’s center of power had lain with Greer. “Your photographic contributions were given the same special attention as your written ones,” he wrote. “Both have been an excellent and important part of your canon, an inspiration and example to writers and anarchists…. I have resigned in sympathy with your disappointment with Suck. We all have!” Greer had toppled Levy, who had become the magazine’s de-facto patriarch.

The issue included a retrospective, “Suck Turns Flesh into Words/Words into Flesh,” that acknowledged both the inevitable failures of the publication and the social experiment it represented. “We look at ourselves and realise none of us live in a sexual utopia and if that’s what is projected, it is a lie,” it read. “From this time on, we include our sexual confusions as well as our ecstasies, struggles as well as successes.”

With nearly five decades of hindsight, Tillman concluded, “Suck was a loose collective of very different subjectivities. Each [editor] was on a search for extremes.” This quest for extremes would be bound to fail. But much like the larger sexual revolution, the legacy of Suck hinges on the belief that failed utopian experiments are better than no experiment at all. Despite its eventual implosion, Suck pioneered its own set of “family values” that transcend its cult status in the niche of avant-garde erotica and that continue to percolate through society—among them, an assault on heteronormativity, a first-person articulation of sexual politics, and the forging of a dissonant feminism that agitated for women’s sexual empowerment and autonomy. Suck conceived of pornography in the plural, creating a spectrum of erotica that did not rely solely on the hegemony of the heterosexual male gaze.

The legacy of Suck is not unblemished. Boundary pushing was a central aim of the enterprise, and the results occasionally turned readers’ stomachs: articles and testimonials about incest, images and drawings that come uncomfortably close to child pornography, an account of hot gay sex in a Nazi youth camp, and even a tawdry sexual account of “Bridget the Midget” penned by Heathcote Williams after a stay in a psychiatric hospital. Tillman suggested a common thread: “It didn’t matter whether it was child porn or something else—I think in a way all of it was the same to him. It was what went against middle-class values. Bill was really interested in shocking people.” While this reliance on taboo subject matter to shock remains indefensible in 2018, it ultimately did not sink the magazine during its run. But acknowledging it is crucial to preserving the integrity of the magazine’s progressive contributions. Any whitewashing of the editorial record would diminish the positive legacy of Suck—chiefly, its prefiguration of a sex-positive feminism.

This feminist sex positivity reached its dialectical fruition four years after the magazine disbanded with the publication of Tillman’s Weird Fucks. The fictionalized account of the author’s amorous relationships in Amsterdam and New York serves as an unofficial conclusion to the whole Suck family saga. Despite the bluntness of its title, the novella offers more than just a literary account of one woman’s experiences in the trenches of the sexual revolution. If the masculinist heterosexual cornucopia of the “Golden Age of Porn” was the thesis, and Suck was the feminist polysexual antithesis, then Weird Fucks could be held up as the synthesis.

While Suck had enshrined promiscuous sex as a feminist position, Tillman’s pioneering narrative layered ambivalence, disappointment, and nuance into this premise, effectively forging a new genre of writing on sex by female authors. Weird Fucks does more than simply project male libertinage onto women or chronicle the gratuitous accumulation of notches on one woman’s bedpost—it probes the psychological complexities of sexual conquest and the uncertainties of desire, and it mines the crevices of sexual difference. It also precociously anticipates a whole genre of auto-fiction, including Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick, Lena Dunham’s Girls, Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be?, and Christine Angot’s L’Inceste. In synthesizing the dissonant feminist DNA of Suck and marrying it with literary ambition, Weird Fucks was largely responsible for carrying the legacy of Suck into the cultural mainstream.