Model Benedetta Barzini answered the curse of her cold Italian dynasty upbringing with radical feminism and a surrogate family composed of Salvador Dalí, Lee Strasberg, and Andy Warhol. Despite the good company, she is no fan of New York City.

I spent a Christmas with my aunt Benedetta Barzini the year before I moved to New York and asked her for words of wisdom as she had lived and worked there as a model during the most wild and fervid years the city has probably ever known, the Sixties, but she stared into my eyes and said: “It’s a cold, cold, noisy place.” We left it at that. Up until I moved, my understanding of Benedetta was that she was a fragile soul with a profound sweetness and intense vulnerability. Each time we saw each other she would lean towards me, batter her lashes on my cheeks, and give me what she called “butterfly kisses.” I had experienced her as a family member, living communally with her two children, Irene and Beniamino who I adored — her first two children, twins, having already grown and moved out. I knew she was a former model, a mother, a professor, and, as I could tell from the imperious Lenin poster that reigned in the entryway of her Milan apartment, a true Marxist.

Even though she came from a sophisticated background, being the daughter of heiress Giannalisa Feltrinelli and Italian journalist and author Luigi Barzini, Jr. in her apartment no rooms were designed for formal activities. Christmas was not celebrated; dinners were served in the kitchen, as opposed to the dining room where most Italians eat. The house doors were always open. Her beauty and charisma, of course, shone through despite her will to keep them under control. Her eyes became deeper and softer with time and her unapologetic streak of white hair, more abundant. She claimed her choice to live a quiet lifestyle, where ghosts and glories of the past would hardly ever be revealed or spoken about. That was the Benedetta I knew.

When I moved to New York though, through friends in the fashion world, I started, like an involuntary detective, putting together the pieces of a woman I had never met: a supermodel who inspired members of Andy Warhol’s factory, an icon who had been the muse of Irving Penn and Richard Avedon, an actress who had worked closely with Lee Strasberg at the Actor’s Studio, an artist who prepared light shows for Velvet Underground concerts, intimately involved with Dalì and courted by the Kennedy brothers. “Intelligence invents beauty is the personification of the feeling I had when I first stood in front of Benedetta,” says poet and photographer Gerard Malanga, who introduced Benedetta to Andy Warhol’s factory, and was intimate with her while she lived in New York. So I wondered: why did my aunt hate New York so much if she had lived there the life that anyone else would dream of living?

Benedetta Barzini–New York is noise to me. Even though I was born in Italy my mother hated everything Italian. She moved my sister and I around compulsively around the world to make sure we would never feel at “home”. I was in New York the first time from 1950-55, the McCarthy period, living in a hotel with my mother and sister and our governesses, going to a French school on 96th street. I was miserable living in a hotel and wanted to have a normal family like my like my friend Roberta Fryman. She would tell me stories about taking baths with her family on Sundays and I thought it was incredible. I had no contact with my mother. She lived on the 16th floor. I was on the 3rd with my governesses, maids, and sister. On Sundays the governess would say: “Come and say good morning to maman”. We would say “good morning maman” and leave. Most of the personnel of the hotel were Italian like me, but I wasn’t aloud to speak that language, just French and English. Italy was mysterious to me except for the scenery. In summers I would drive through the country by car looking at everything through a glass window. We would be locked up at La Cacciarella, (a majestic summer villa and private park on the shores of Mount Argentario in Tuscany) and couldn’t even go to the village for an ice cream because my mother had given orders that ice creams in Italy were “bad” and everything that came from Italy was “bad”. Don’t ask me why. I have never really known her.

Chiara Barzini–So though New York was a temporary first home, you never lived the emotions of a family nucleus there?

Benedetta–Once my mother invited me to sleep in her room on the 16th floor. It was the only time I had ever been allowed into her environment. She had a box of gummy blackberry throat candy and I ate them all.

In the Navarro Hotel there were a lot of Italian Americans and I genuinely became homesick for a home I never had. I became extremely conscious of the problem of immigration, of feeling eradicated and without a base. I would listen to an open radio show under the sheets where Italian-American were allowed to speak freely to their relatives back home. You would get this atrocious feeling of people in New York crying out “Mamma! Papà! Figlio!” across the ocean, as Claudio Villa sang about the “Terra Straniera” [foreign land]. I cried listening to those voices, even though I often did not understand what they were saying because they spoke in regional dialects.

Chiara–When you moved back to Italy in the’70s after your modeling years, you became a real political activist and joined the Communist Party. Do you think, perhaps your early relationship to immigration had something to do with this?

Benedetta–Since I was young I knew I belonged to the left wing. I remember the poverty in Rome after the war. I would be strolling with some nanny around the Terme di Caracalla and would see the people who had remained homeless, all standing behind a metal fence. That vision left a mark. I also had a very strong link to my brother Gian Giacomo Feltrinelli [the pioneeristic European publisher who was deeply involved in the Communist party and died in 1972 while trying to ignite a terrorist bomb on an electric pole close to Milan]. We had been harmed by the same mother and so I could observe what too much money could do to people.

Chiara–What was your relationship with the Feminist movement?

Benedetta–A very strong base for continuing to observe women’s condition. Feminism, whether or not organized in visible movements, is inevitably part of modernity. My coming back to Italy in ’72 after modeling meant “ok now I can begin to ‘live’.” I entered The UDI: Unione Donne Italiane [Italian Women’s Union] – an organization created by mostly Communist women after the war. I became responsible of a work committee. The most formative experience was coordinating the 150 hour project – helping organizing female factory workers in the outskirts of Milan. Now I am not a member of anything and hardly go to marches, but when I teach my classes [Benedetta is a Professor of Fashion and Anthropology at the Polytechnic Institute of Milan] I explain why men have one outfit and women thousands, and the fact that having thousand of outfits basically equals to having nothing.

Chiara–Let’s rewind back in time for a second. When the “empress of fashion” and at the time Director of Vogue, Diana Vreeland saw a photo of you that Consuelo Crespi took in 1963, she phoned and asked you to go back to New York and shoot for Vogue. You had been living between Italy and Switzerland then, and had been anorexic for some years already. Your family had sent you in and out of high-end private clinics and facilities. I’ve always found it interesting that this sickness was with you before you became a model.

Benedetta–My sickness came from the fact that everyone that I had ever love could not last. All my governesses (once I counted 17 of them) were constantly fired. The people who belonged to my so-called family did not exist. I was a very unwanted child. I consider my anorexia as the beginning of coming to sanity because it’s insane not to be sick if you have a really broken up life. Sickness is a sign of sanity, a desperate need for sanity and normal life. I had a sense of calm and tranquility in the idea that my body was vanishing, that there was no body. When you’re deeply anorexic, you don’t feel anymore: not pleasure or pain. No needs, no hunger, no emotions. That was restful for me. Also there is a very ancient link between anorexia and family dynamics. Refusing to eat is one of the very few things that women in the past could do to go against the will of their families. Not eating or refusing to eat is a political protest against some form of establishment and I slipped into this rebellion. I don’t think one is ever really cured of anorexia. I learned a certain form of stoicity. When you’re that skinny and the only thing that’s alive is your mind, a kind of rigor sticks with you. You have incredible, mysterious energy that comes through your mind. That has stayed with me as well as the idea of “invisibility”. I now live a very solitary life. I am not a very social person. I don’t care to be seen anywhere.

Chiara–So the period before getting back to New York was quite an odyssey!

Benedetta–I escaped the last Swiss sanatorium by jumping over a wall and a barbed wire fence. I hitchhiked to Zurig where my friend Giuppi Pietromarchi and her husband took me under their wing and helped me get legally emancipated from my parents. I loved them and am grateful to them because they never said I was crazy. At that point I was 18, I wanted to draw, and I managed to get into the Brera Academy drawing class. I found a job in an art gallery. I started regenerating myself. When Diana Vreeland called me to shoot for Vogue, I felt for the first time that someone wanted me, specifically me, and it felt good. So I told myself I would do my very, very best to please them for having wanted me. Eileen Ford came to the airport to pick me up. I was a little skinny thing traveling alone. They placed me in a hotel and life began. New York was still too big, too noisy, too much, but I loved the MOMA where I went for drawing classes. It was my refuge. I also found a therapist and went into intensive therapy and started getting well. My period came back, my tits started growing. I wasn’t going to play with life and death anymore. Working in New York was my medicine.

Chiara–Who were your first new friends?

Frederick Allen would take me out to eat. He taught me how to love Bach. David Whitney and Philip Johnson invited me to spend my weekends in Johnson’s amazing glass house in Connecticut. We would sit there in front of the fire and talk. I was also saved because I followed Lee Strasberg’s classes in Carnegie Hall.

Chiara–Even though working helped you heal from anorexia, as far as I remember you’ve never spoken too generously of modeling as a career.

“I never walked around with heavy make-up. Same thing now. I don’t worry about my hair or the wrinkles on my face, and the editors of Vogue don’t like that.”

Benedetta–Working as a model is a scheme. It’s the same as working as a prostitute. It’s the merchandise of the body. It’s not on an absolutely sexual level, but your body is for sale; your face is for sale. It drove me, when I came back to Italy, straight to work in the women’s movement, not because I shared their political ideas, but because I wanted to fight the idea that women represented “pleasure” and men represented “reason”. You can see this in clothes. In menswear there is a form of respectability and credibility, but if women want the same effect, they must wear a jacket.

Chiara–Was there any time that you actually enjoyed the shoots? Were they ever fun?

Benedetta–No. I resent the word “shoot”. My feeling is that it is exactly what it means — a sort of sexual thing, also. The hunter has to get the prize. “GIVE ME THE LOOK.” My feeling was that I had been shot all day long. Of course I got along with everybody. I was gentle. I learned how to behave professionally. I would walk in the studio and concentrate on how to convey in the photo the shape of the dress I had on. No matter what they did with my hair or my make-up or shoes or accessories, what was important was how I could portray the style and the significance.

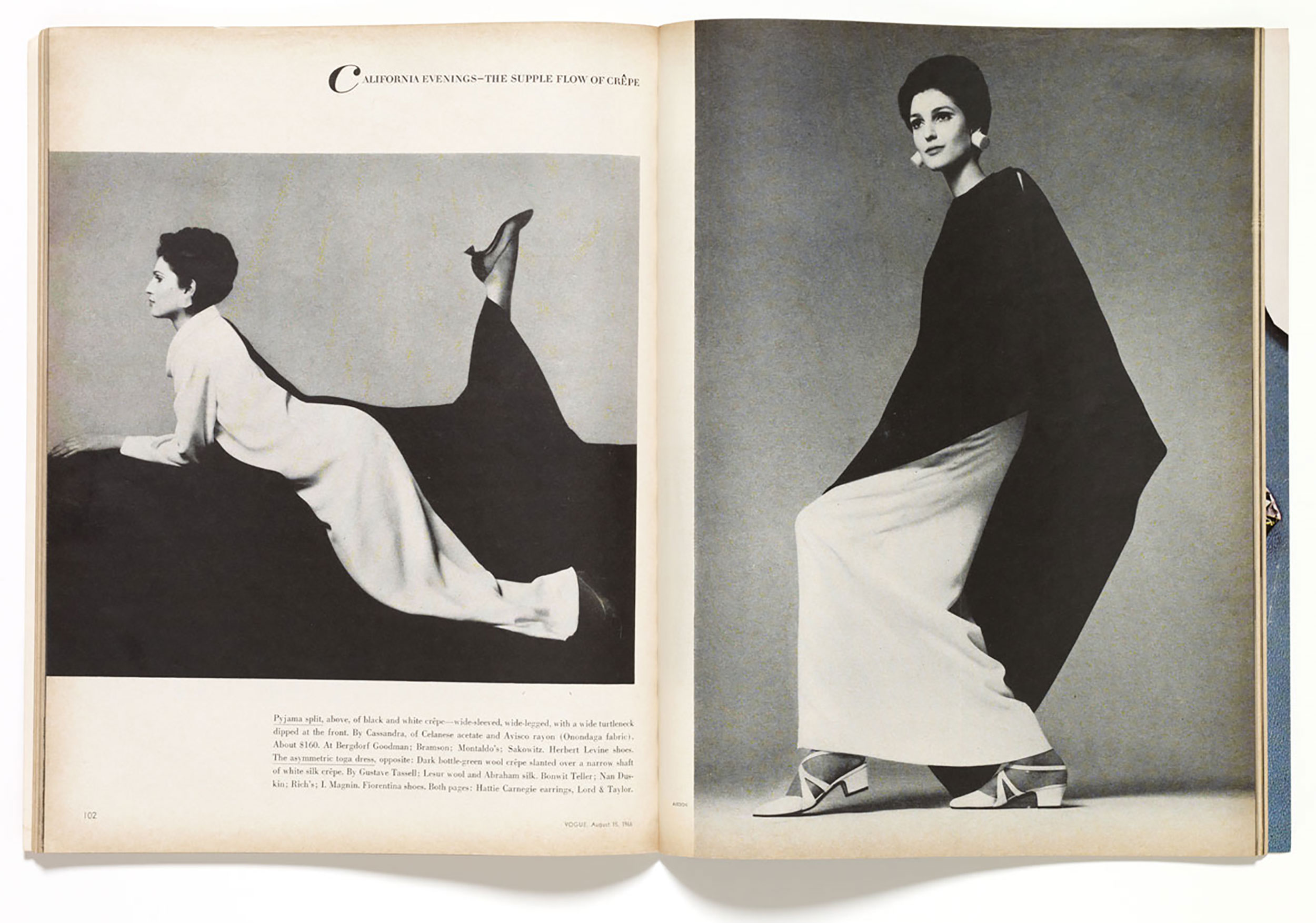

Chiara–In your photos from that time, especially the ones by Irving Penn, there is something in the way you interact with your surroundings, the symmetries you create, and the way you are in relationship with what you wear and the accessories, that is very signature “you.”

Benedetta–As street wear was coming to life, high fashion was becoming the “dreamland”, and that’s what we created. We invented shapes or movements where reality was not involved. My role, my “talent”, was how to bring out the significance of what the author of the dress wanted. I worked 80% of the time with Penn who was just as detached about fashion as I was. He was a very distant person, very educated, gentle, sweet, and proper. I felt like he was working in fashion to have money to do his own thing. Normally there would be a table of accessories, shoes, hats, gloves, and scarves. And Penn would fall asleep under the table waiting for the girls to get ready.

Chiara–Avedon was different though…

Avedon was a jumping bean with wild music going all day long in his studio, whereas Penn’s studio was behind the public library, a quiet place. Avedon was playing the part of the fashion photographer, hopping all over the place: “More rouge!” I think he was high. I didn’t like working with him at all, because it was totally phony. “Jump, jump!” he insisted, instead Penn was extremely composed. I met up with Avedon many years later in Milan where he was doing an art show and finally admitted to him that I had hated working with him. “You know what, Benny,” he told me, “I really hated working with you also.” It was nice to be upfront, outside of our “professional” context so many years later. In fact we ended up working on a campaign just after that encounter. It was honest.

Chiara–In New York you rejected the fashion world and Eileen Ford’s parties–even though the Rolling Stones would play at them–because you were in search of something different. Was Andy Warhol’s factory a good alternative to the fashion world?

Benedetta–The factory was a bit like a medieval piazza and maybe that reminded me of home. There was a group working with music in one corner, another group of poets in another corner, people shooting up in another corner. Everything was happening simultaneously in one, flat huge loft: minstrels, mad people, strange, drug addicts and Andy would be in one corner. My days were before the “Chelsea Girl” days, before the filming began. We went with Nico in tour in Boston. All my students now tell me: “Oh my God, you used to hang out with Lou Reed!” But at the time I didn’t know he was “Lou Reed”. At the time he was just a scruffy-looking guy. Sure I am angry with myself for not realizing what was in front of me. If I had saved three scratches by Andy or Dalì, things would be different today. There I was, walking in Central park arm in arm with Dalì, going to the Hutchinson where he had his show, and the last thing to come to mind was “Hey, give me a scribble”. At the time I was just walking with a friend.

Chiara–What was your relationship with Dalì like?

Benedetta–He liked me and was somewhat like a “father” figure. I was curious and often had tea with him. It was a strange friendship that easily went down the drain, but I think he understood my uneasiness about life and I understood his paraphernalia and excess baggage. Once we were sitting in the Saint Regis having tea and he was going on with his imperious, loud tone, and I said: “Why don’t you stop? Tone it down.” He grabbed my hand and said dramatically: “You know Benedetta, if you had had a brother who died when he was nine and they called you like him, and everything you did, he had done better, you too would have invented things that your brother would not have done.” I froze right then. We couldn’t do much for each other, that’s for sure. We were publicly involved, but I think Dalì had no interest in sex and neither did I, so that was something in common between us.

Chiara–Still, it was a very intense and interesting moment in history and art. Maybe you didn’t realize it, but surely you must have felt it?

Benedetta–I felt it was important, it was interesting. But I didn’t have the awareness of going beyond that, investigating more, studying more. I remember attending the opening of the Whitney Museum and seeing all the American art there. But then again, it didn’t go very far. I was locked up and trying to get well, and doing my job and not going to bed too late, and not getting drunk or doing drugs. Timothy Leary was living in New York and everybody was on LSD . . . I mean everybody. And I didn’t want to touch drugs.

Chiara–Did you ever do LSD?

Benedetta–I did, once, but it scared the wits out of me. I had to keep myself under control. I was scared stiff.

I was at the house of a hairdresser called Galant and there were other people there. In the morning we all went out to get coffee and I remember sitting on the stool and falling off because I felt a river pushing me away.

Chiara–Did it seem like it was a bit much? Maybe you were overwhelmed by the times?

Benedetta–If you want to create a world where there are civil rights, where there are black people, and young people and hippies expressing their movements, proposing communes and natural food, you are bound to be scared and look for solutions. It’s a scary thing to bring into the world so much novelty. Drugs help you overcome the fear of going against the establishment somehow. They give you courage and keep you open to the dream world.

Chiara–How did you decide to do the lighting for the Velvet Underground tour?

Benedetta—Andy asked me. There was a big rectangular building with a balcony and a stage and the Velvet Underground were playing downtown somewhere in the Village. We were on the balcony, me on one side, Andy on the other, and there was a projector that projected behind the Velvet Underground. I didn’t like that music; I didn’t like anything. I mean I liked Joan Baez. I didn’t even like Bob Dylan. But everybody was playing Bob Dylan all over the place. In the end I liked Bob Dylan ok but I didn’t like the noisy things like the Rolling Stones… The Beatles? Yes, but boring. That was my spirit. I wasn’t caught into any net of that kind. Then I got back to Italy and started to appreciate it all.

Chiara—You were not a scenester, but you were curious and because you came from a rather sophisticated European background you could easily pick and choose any milieu. You went from the downtown crowd all the way up to Fifth Avenue in Jackie Kennedy’s apartment.

Benedetta—Jackie had invited me to her house because she had read my father’s book, “The Italians”. She had loved the book and liked him very much. We had dinner at her place then we would all go to Robert’s [Kennedy’s] birthday party down the block on 5th Avenue. Stokowski, Bernstein, and Mike Nichols were there. My memory of the soiree is “beige”. Jackie wore beige and looked like a cartoon. We ate beige food and wiped our mouths with beige napkins. I went to the bathroom to see what it looked like–if you want to understand something about someone you have to go to their bathroom–and it was very chic and elegant, and of course beige. After dinner we went to Bob’s birthday party. There were lots of elite socialites in the powder room, fixing their dresses and putting on make up. I didn’t now what to do with myself. I remember Teddy sitting next to me and saying: “Oh Barzini, did you know we are the Caesars of America?” At the party the lights went off in came a huge cardboard cake brought in by four men. They put it on the floor. We all sang and out popped a bunch of playgirl bunnies… I just kept thinking “The Caesars?” Then Teddy told me he would have liked to see me sometime. I said, sure, but when he finally had his secretary call me, he told me he could only see me at 1 am in the night and asked to please enter through the back door. I said I was sorry but couldn’t go in the back door in the middle of the night, so he stopped calling. I realized was supposed to act like an escort, very similar to what Berlusconi does in Italy today. But I had a sixth sense and knew where to stop.

Chiara—Just a few years after being courted by the Kennedys and hanging out with the crème de la crème in New York, you returned to Europe.

Benedetta—Like I said I did not want to marry a rich American to have my paperwork and I didn’t want to go to Eileen Ford’s parties to flirt with her clients, so soon enough the phone stopped ringing. I couldn’t be used for commercial work, because I was too “exotic” and “Mediterranean”. I would have sold only to Latinos and Italians. Today models are more aware of the fact that their bodies are their “company”. They change the color of their hair, their eyes. They resell themselves on the market. If you treat yourself like a company, people will really make money from you, but if you don’t, you will stay right where you are. The amazing thing about the momentary occupation of being a model is that if the phone doesn’t ring, there is nothing you can do. You can’t send your CV. You can’t go on auditions. You can’t do anything except for wait.

Chiara—What is your relationship to Vogue Italy now?

Benedetta—They don’t like me and I couldn’t give a damn. Every once and a while they call me and ask me to write something for them. I never went around with my book looking like a model. People would look at the photos then glare at me, “is that you?” I thought it was a plus to not look like I did in pictures, but it was a minus. I never walked around with heavy make-up. Same thing now. I don’t worry about my hair or the wrinkles on my face, and the editors of Vogue don’t like that.

Chiara—Today in Italy you’re not just teaching the history of fashion, you’re teaching people that what we wear is representative of something else, so you’re teaching younger generations how to think and what to question, which in a sense is what you did with me when I came to you for advice.

Benedetta—You cannot study history without facing women’s conditions. The clothes they were forced to wear absolutely determined their role in society. There is not one woman who said in the past “bullshit! I’m not going to wear a corset.” When I came back to Italy I didn’t have any nostalgia about modeling. My problem back then was the fact that traveling so much I hadn’t gone to school, I hadn’t finished anything, and hadn’t graduated from a university, but when I got asked to teach, I started studying like an animal. It dawned on me that to teach fashion I needed to study history, sociology, and anthropology. I needed to know how to place clothes in various periods and to place them within the realms of politics and power. Being invited to teach the meaning of clothes in history was a way of giving significance and making sense of my modeling career, and being able to help others on their own paths.

This conversation first appeared in Document’s Spring/Summer 2013 issue.