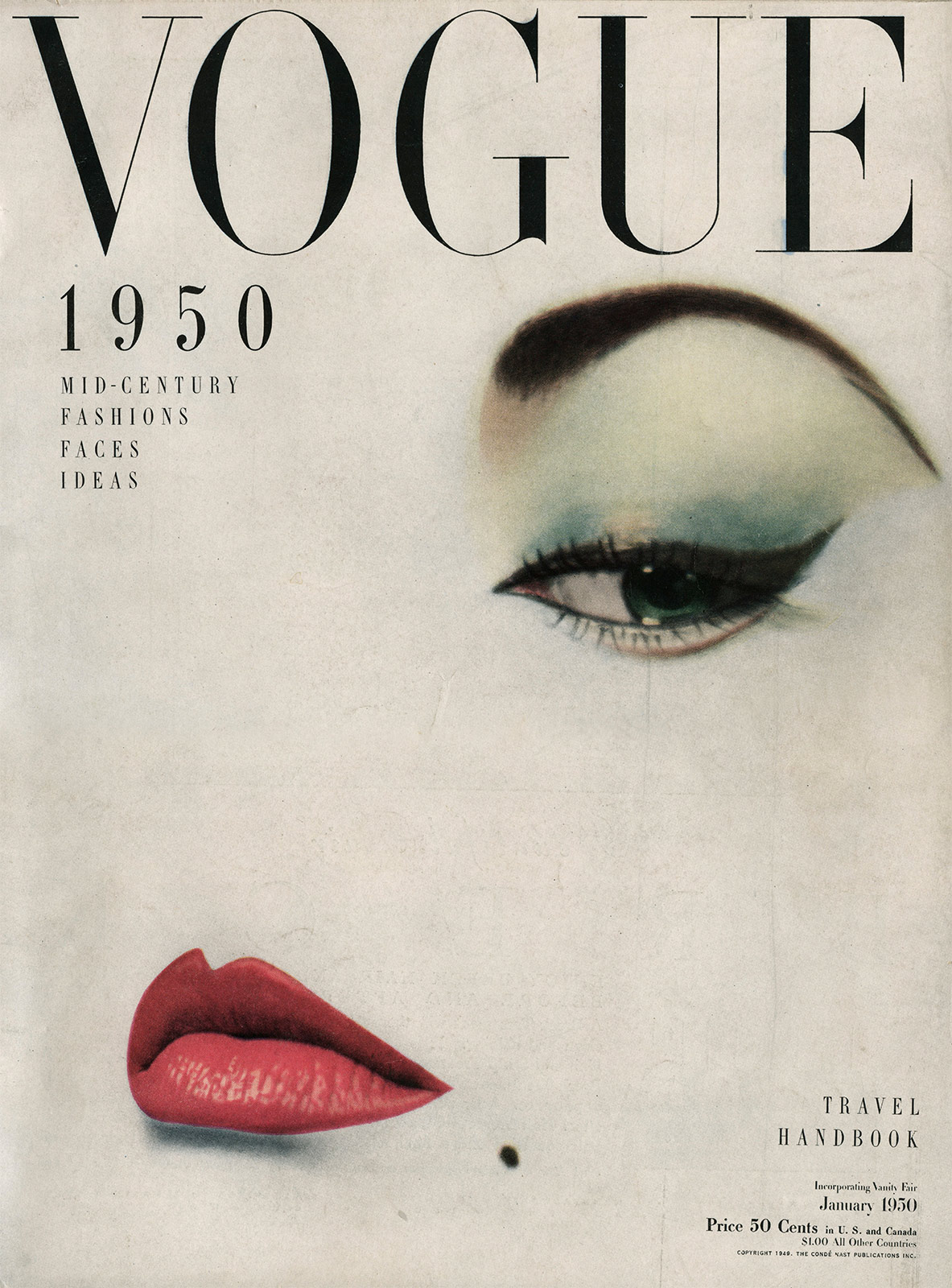

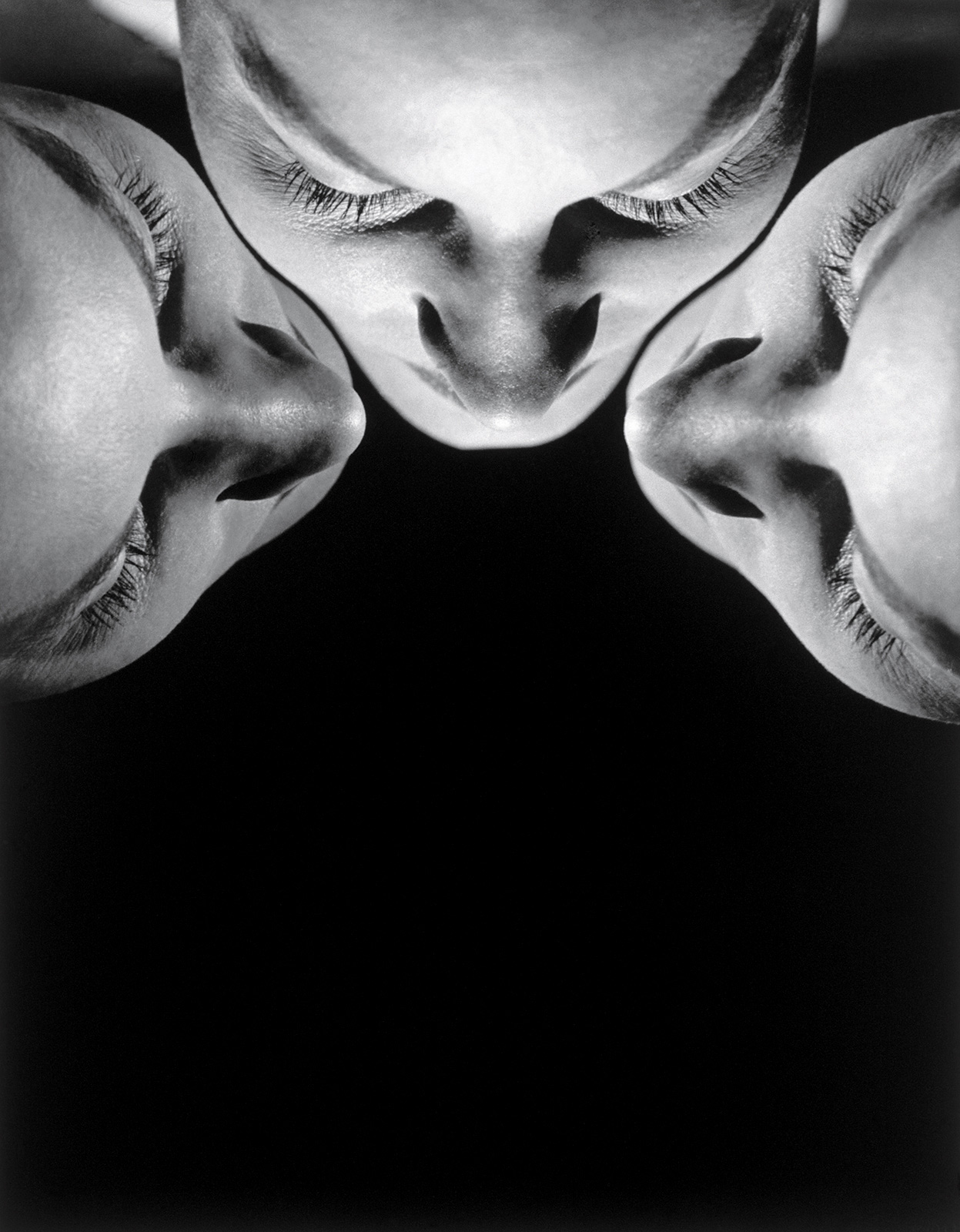

Between 1944 and 1955, Erwin Blumenfeld photographed nearly 50 covers for American Vogue, but the one he contrived for the magazine’s January 1950 issue is the most celebrated. In a composition still astonishing for its drop dead elegance and graphic impact, a woman’s arched eyebrow, watchful green eye, crimson mouth, and beauty spot are isolated on a white ground. The model Jean Patchett, a favorite of Penn’s and Avedon’s, is reduced to a Cheshire cat like presence but elevated to an enduring icon of mid-century beauty and sophistication. Two years later, Blumenfeld devised a similarly stark but even more striking cover for Vogue Beauté, a supplement to French Vogue. Here, a mesmerizing row of three delicately shadowed eyes (two blue, one hazel) stare out from a stark white ground above three perfect red mouths in a surreal vision of seductively alien allure.

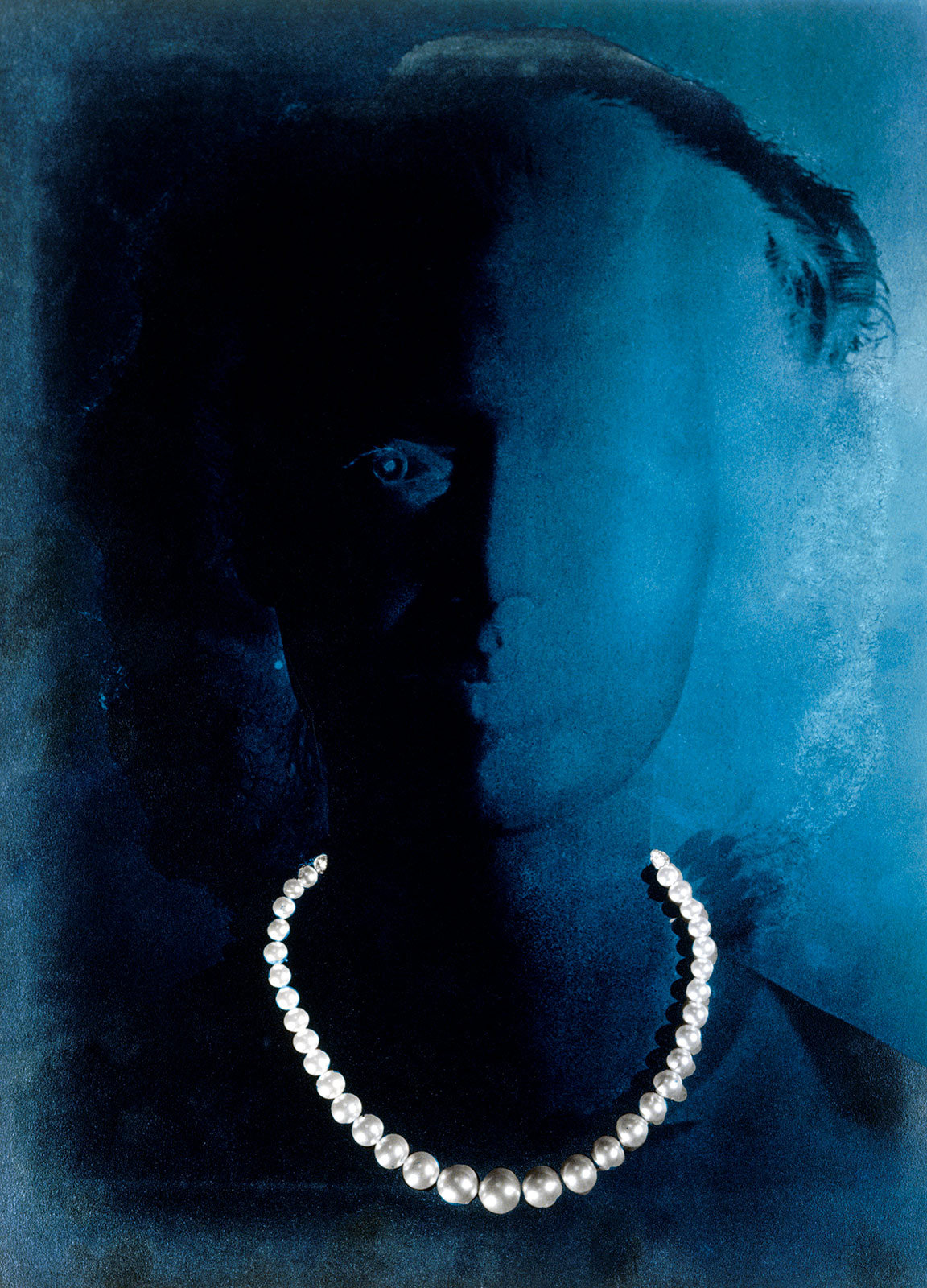

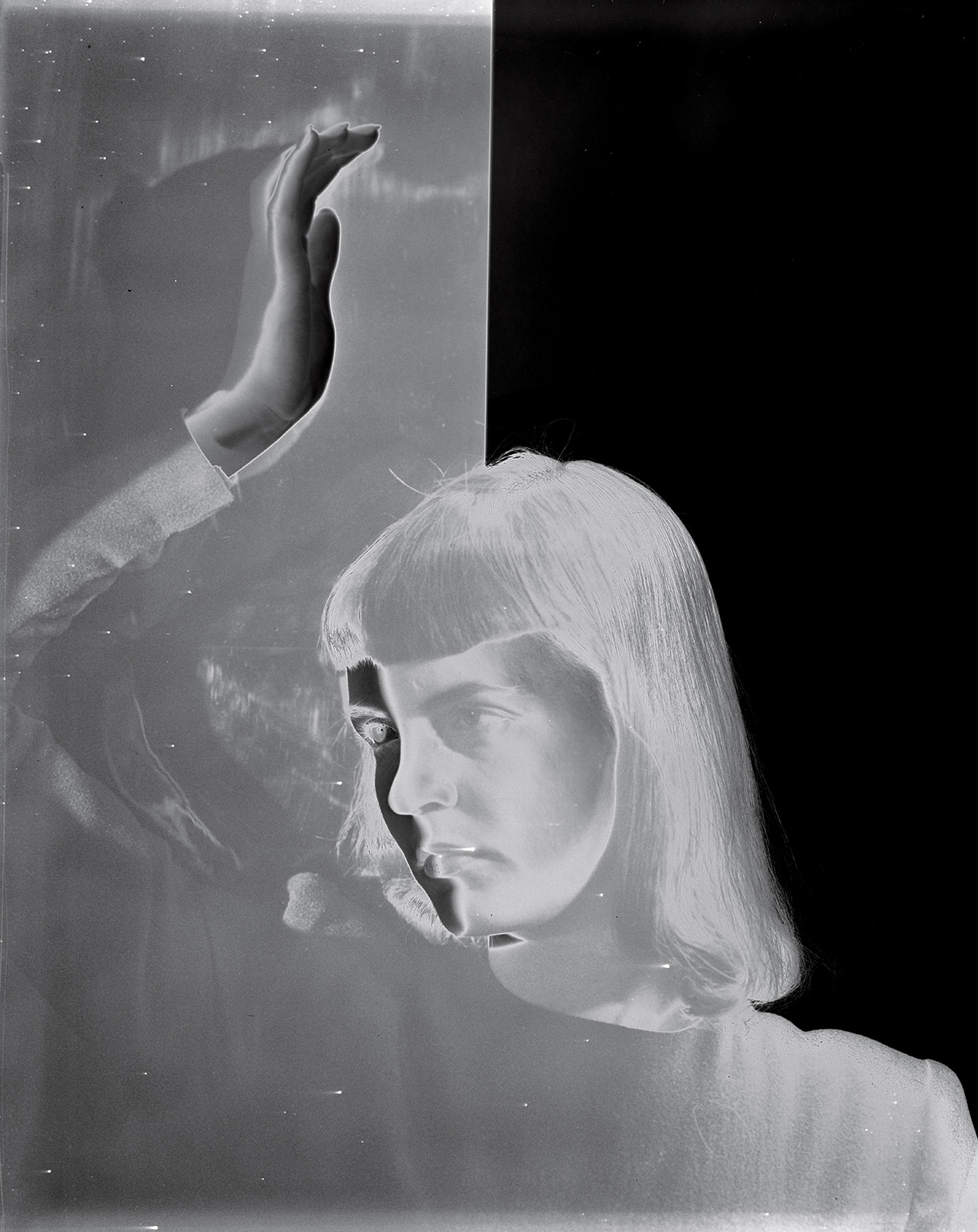

As those covers and the selection of photographs in these pages makes abundantly clear, Blumenfeld’s work could be classically chic or radically avant garde but it was never merely conventional. Alexander Liberman, the art director of American Vogue during Blumenfeld’s years there, called him “the most graphic of all photographers, and the one who was most deeply rooted in the fine arts.” Although Blumenfeld made plenty of “straight” photographs, they rarely appeared that way. He magnified, miniaturized, or doubled his subject; he used mirrors, textured glass, veils, netting, colored lters, and distorting lenses. But many of his most inventive photographs involved darkroom techniques—solarization, bleaching, multiple exposures, and chemical manipulation—that even Man Ray had not introduced into fashion magazines.

“The technical work is the greatest joy,” he told Cecil Beaton, who had helped smooth Blumenfeld’s way into both French and American Vogue. “To me, the greatest magic of the century is in the darkroom.” Following a brief stint at Harper’s Bazaar’s Paris office—brutally interrupted by the German invasion of France; when the Berlin-born, Paris-based photographer was thrown into a series of French detention camps—and, once he’d fled occupied France, a year at Bazaar’s New York base, his decade at Vogue was remarkably productive. By 1947, the New York Times was describing Blumenfeld as one of the highest paid photographers in the United States, with a number of lucrative fashion and cosmetic advertising accounts as well as a broad range of magazine work. Readers of his witty, acerbic autobiography, Eye to I, will not be surprised that he had a falling out with Vogue in 1955. He had little patience for what he called “arse-directors,” and refers to Vogue’s Edna Chase, Bazaar’s Carmel Snow and two of his main ad clients, Helena Rubenstein and Elizabeth Arden, as “those midnight hags.” “In the short span of a single generation,” he lamented, “the cultural heritage brought from Europe has been watered down to a tasteless soft drink.” Blumenfeld wasn’t interested in serving soda pop; his photographs brought avant-garde experimentation to the fashion pages with the invigorating fizz of vintage Champagne.

Curator and critic Vince Aletti wrote this homage to Erwin Blumenfeld’s enduring vision for Document’s Issue No. 1.