East Village Eye uncovered the brightest minds of 1980s New York. Thirty years later, editor Leonard Abrams finally shares its story in Document S/S 2018.

In the mid-1970s, New York City’s East Village seemed an unlikely incubator of creative activity. City-wide economic collapse and endemic crime exacerbated the diverse working-poor neighborhood’s disenfranchisement. From Houston up to 14th Street spanned blocks of burned-out buildings (often occupied by heroin addicts), trash heaps, junk shops, and ramshackle tenements. As a result, East Village rents were among the cheapest in the city. This affordable—if precarious and untenable—housing situation, combined with a lack of available venues for upstart rock bands, began drawing tribes of proto-punks to the haunts along Bleecker and Bowery, undeterred by rat stampedes and daylight stickups. Over the next decade, drag queens, performance artists, fashion designers, painters, and partiers joined them. The urgent energy bubbling up at CBGB, the crowded and raucous hub for the local music congregation, soon flooded the neighborhood.

A new generation of multidisciplinary artists in the East Village shrugged off the weight of their grim futures. Unburdened by high costs of living, they established hybrid art-nightclub spaces, where they danced to new wave, punk rock, and hip hop music, exhibited artworks, presented fashion shows, threw elaborate theme-parties-cum-performance-pieces, and screened underground films. They eschewed traditional galleries by opening their own in small storefronts or staging guerrilla-style shows at abandoned sites. They created dynamic and accessible artworks shaped by experimentation, collaboration, radicalism, and fun. These artists shared a neighborhood, but not an aesthetic style born out of common goals or sensibilities. Rather, the East Village scene was guided by an attitude of irreverence and freedom. At the crossroads of this messy, vibrant ecosystem was the East Village Eye. Its editor and publisher, Leonard Abrams, launched the monthly paper from a basement storefront on Ludlow Street when he was 24 years old. A former bike messenger with a lifelong interest in journalism, Abrams created a platform to investigate and celebrate his unique community. An ever-revolving roster of contributors reported on the neighborhood’s housing and public health issues, art happenings, vegetarian restaurants, and youth-quake musical movements with satire and sincerity.

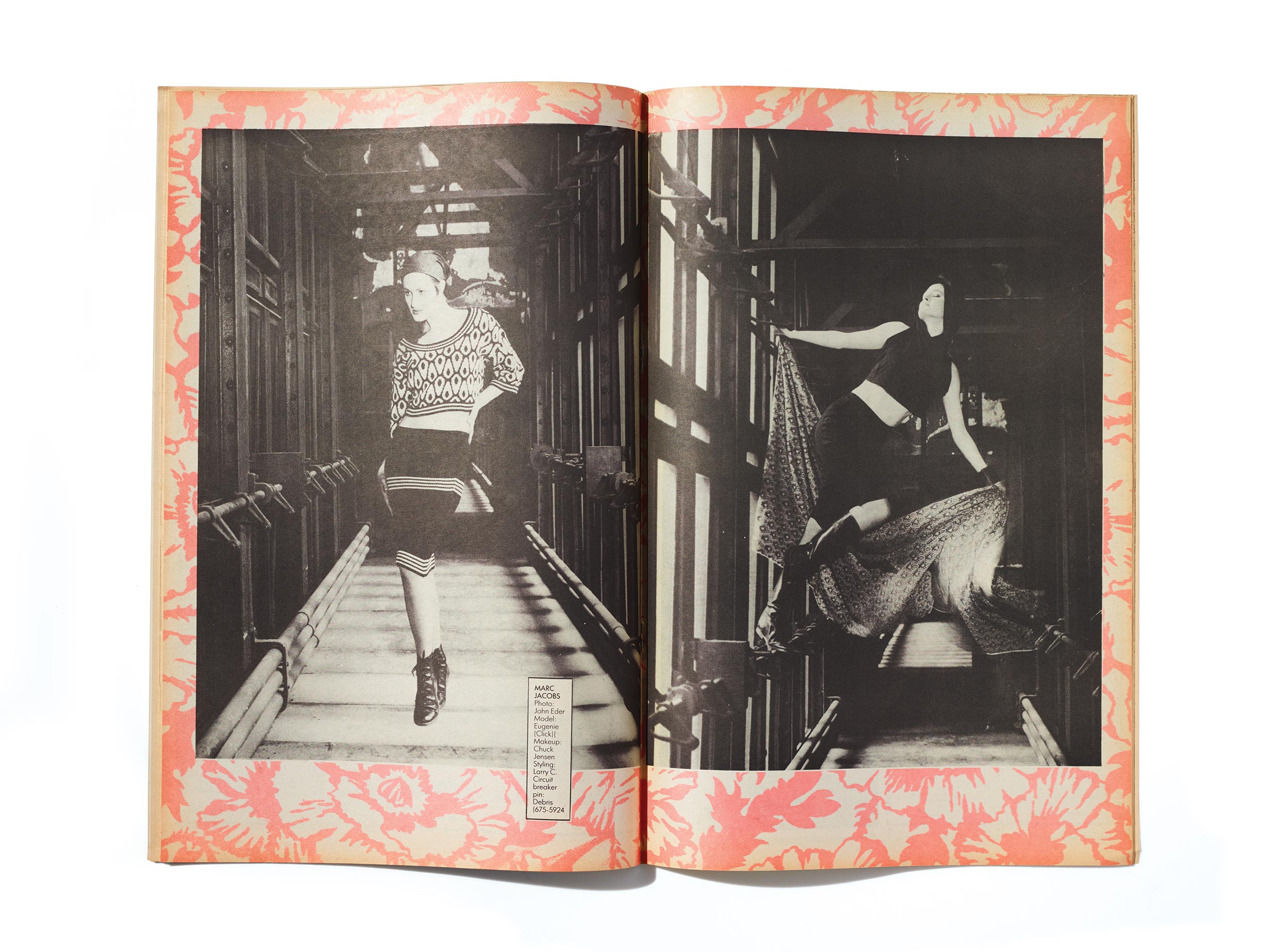

The East Village Eye published 72 issues between May 1979 and January 1987. Over these eight years, its masthead featured downtown luminaries like Gary Indiana, Richard Hell, Rene Ricard, Lucy Lippard, David Wojnarowicz, Steven Hager, Ellen Berkenblit, Marcia Resnick, Sylvia Falcón, and Collier Schorr. Glenn O’Brien wrote about sports. Cookie Mueller published a homeopathic health column. Inside a typical issue of the Eye were reports on labor rights violations and recipes for tandoori chicken. Take, for example, the April 1983 edition. The issue included reviews of an 18-day sleaze film festival, a Prince concert, Charlie Ahearn’s pioneering graffiti film Wild Style, and a Richard Hambleton exhibition, as well as a fashion story photographed at the Church of the Holy Communion—the Episcopalian house of worship built in the mid-1800s that was soon to be reopened as the legendary nightclub Limelight. Also to be found in the issue was an interview with the Thompson Twins and the president of the Ninth Street Center, a vital resource for queer people, along with helpful tips for not getting mugged.

By the time the April 1983 issue hit stands, the East Village was at the apex of its cross-cultural creative renaissance. The Eye’s multiplicity of perspectives echoed its arena and the limitless expressive possibilities that seemed to exist there. But just two years later, in 1985, Eye contributor Carlo McCormick penned a eulogy for the gentrifying neighborhood and its commodifying galleries. As quickly as the East Village art scene emerged, it dissipated. Thirty years after publishing the Eye’s final issue, Abrams shares its story.

“My interest in publishing first developed because, well… What it comes down to is that I’m a Sagittarius. We have a deeply felt sense of justice. Also, my father was a firm believer in the importance of reading the newspapers. I took that to heart and started reading the papers when I was 12 or 13. I started an underground paper in high school called The Spring Valley Alternative. Something had happened at the school that had pissed me off. They had changed the parking rules, or something. So I thought, ‘All right, time for a little activism.’ We did two or three issues. This was 1972, so there was a lot of rebellion in the air, a real feeling that changes were happening. People got excited about [the paper], and I had supporters right away. But the teacher who was the adviser to the official school paper, The Spring Valley Tiger, got really mad! I was delighted to make someone mad at me. Another paper came out around the same time, a more underground, more radical paper. It was called Students Having Interesting Thoughts, or SHIT, and was later published as The Tiger Turd. I started having negotiations with them to see if we could combine forces. These high school experiments with journalism made me realize the extraordinary power you have to affect the discourse, simply by publishing something.

I went on to Fordham University to study comparative literature. Later, I was a bicycle messenger, and I shared an apartment on 63rd Street—in an old complex called the Phipps Houses—with another bicycle messenger. The rent was $128 per month, and you could make it in two days as a messenger. I then got my first apartment in the East Village in 1976, on the Hells Angels block of Third Street, between First and Second Avenue.

“Living with the threat of somebody breaking into your apartment was not really as bad as having to deal with your relatives, or your small town, or your employer.”

When the cultural explosion happened in the ’60s, all of these runaways came into town. But when the harder drugs took over and people started dying, a lot of people were drawn out of the city by the hippies’ back-to-nature movement. The whole scene kind of imploded. So, in the mid-’70s, it was quiet, and it was an easy place to live, although buildings were catching fire all of the time. Landlords would just pay somebody to set the place on fire so they could collect the insurance money. There was a lot of devastation going on, but I don’t think the creative activity in the East Village was born out of the destruction. I think the most important thing was that so many people didn’t have to work so much, or even at all. When I started the East Village Eye, I was just living on, I don’t know what, air? And there was a lot going on in the culture in the ’60s: Vietnam, the bomb, civil rights, riots. This caused a lot of discord and stress in families and in communities. Young people gravitated towards downtown New York because living with the threat of somebody breaking into your apartment was not really as bad as having to deal with your relatives, or your small town, or your employer. When all these people got together and started doing all this work, great things came out of it.

Before I started the Eye, I was working for the Gramercy Herald, a neighborhood publication. I talked the editor into letting me do an advertising supplement, and I did a big story on the New Wave Vaudeville show. I found out about it through flyers posted on the street. I saw ‘New Wave Vaudeville’ and didn’t need to know any more than that. I interviewed the producers, Tom Scully and Susan Hannaford. I remember asking Tom and Susan why they were calling the show New Wave Vaudeville. They said, ‘Well, we just thought it’d be a good name.’ What struck me about that answer was that they did not want to have to define what new wave was, nor what was punk, nor what they were doing. They just wanted to do it.

So I went and saw it. There was a guy doing a magic show dressed up in S&M leather gear, and Ladybug did a striptease, breaking the feminist taboo against the objectification of the female body. Her performance was proclaiming that people were going to do whatever they felt like and not censor themselves. David McDermott sang I’m the King of the Nile dressed as King Tut. He did a striptease, too! Kristian Hoffman played baby Jesus, singing I Put the X in X-Mas Day. Goofing on Christianity was just one example of how this group of people, the Club 57 kids, were obliterating accepted social mores. Especially considering their club was in the basement of a functioning church.

Then comes Klaus Nomi, doing this operatic aria in his full getup and with a smoke machine. Klaus was in a category of his own. Sexually ambiguous German punk kink. I don’t know anyone else who did anything like it. People were very enthusiastic about Klaus’s performance, even though they didn’t know what to make of it. Who can sing like that? There was such a sense of newness to everything that night.

The first Eye office was in a basement storefront at 167 Ludlow Street. I had an apartment in the same building. There was a guy who was either moving out or moving upstairs, and it was the artist Christof Kohlhöfer. We met, and I told him what I was doing and he said, ‘All right, I’ll be your art director.’ I’d never seen his work. He was art director for the first five or six issues, and brought in this whole appreciation for the significance of art. Chris, who had been a student of Joseph Beuys, communicated this idea of the artist doing what’s necessary in society. That had been enunciated to other people, but not to me. I got it right away and thought it was important. Chris was a member of the artist group Colab (Collaborative Projects), so all these Colab artists got involved with the Eye. Which meant that very early on, we had reproductions of work by John Ahearn and others.

Other things we covered came out of the neighborhood. At the time, the rock music on the radio was crap. When the Eye office was on Avenue B between 3rd and 4th Streets, these kids started coming in to the office from the neighborhood. One of them, nicknamed Pooch, said, ‘You’ve gotta listen to Mr. Magic!’ That’s how I got into hip hop and R&B/disco–funk. You could really feel the energy going into this music. I remember when Hans Keller, a Swiss journalist who was covering hip hop, took me up to Harlem World in 1981. They had all these hip-hop acts, some of whom I recognized because I’d been listening to Mr. Magic: Jimmy Spicer, the Treacherous Three, the Sugarhill Gang. Hans was a 40-year-old Swiss guy with a pencil mustache. But, with Swiss efficiency, he spoke to everyone. I remember the emcee said to the crowd, ‘You’re gonna see some people in here tonight who look a little different. Let’s show them some respect.’ We felt looked after.

The hip hop issue that always gets all of the props is the January 1982 issue. Michael Holman interviewed Afrika Bambaataa, and it was the first time the term ‘hip hop’ was ever printed and defined. That’s how underground it was. But we’d been covering graffiti culture for over a year prior. All you had to do to experience graffiti was have eyes. I used to see those train paintings by graffiti artists when I was commuting to Fordham. We did a center spread on Colab’s Times Square Show in the summer of 1980, and we used a Lee Quiñones train painting for our Christmas 1980 cover. The same artists I became familiar with through Chris Kohlhöfer were bringing the graffiti artists downtown, and we’d be going up to the Bronx, especially when the Fashion Moda gallery opened. So the Eye began covering it regularly, along with everything else.

“There was a guy doing a magic show dressed up in S&M leather gear and ladybug did a striptease breaking the feminist taboo against the objectification of the female body”

I can’t say I created the ideas. I didn’t. I took the ideas that were floating around and best reflected what I thought was important. Society’s fate seemed to be in the hands of artists. People were not as interested in politics directly because a lot of people realized that they didn’t have the answers. Politics comes in when you’ve decided what you think you know, and you want to do something about it. ‘Stop the dam!’ ‘Build the dam!’ There were plenty of artists who did decide what they knew and were doing politics in their art. But a lot of people didn’t know. They were attempting to understand, and that’s why they were making art. The paper’s role was to shed our skin and move on to another phase. Our support base was the East Village; the hairdressers, the clubs, the people, the pop music, and the nightlife would support a paper. Building on this base of support, we were going to push the culture forward.

There were some people who wrote for the Eye who just wanted to get their writing career started, and they’d write about any assignment you sent them to. But most of the people who came in to the office had some kind of editorial axe to grind. Typically because their friends were involved in it, or they were passionate about it. Richard Fantina got on board early and did so much great work. He worked at a type shop and supplied the typesetting after hours. All he wanted was to be a part of things. Eventually, he ended up in Alan Vega’s band playing keys, so we had a few extra stories on Alan Vega.

I got to know Cookie Mueller through an interview Sybil Walker had done with her. We became friendly, and one night at a bar or club, she told me she wanted to write a column for the Eye called Ask Dr. Mueller. She also reviewed Wild Style, which Gary Indiana, the film editor at the time, was a little pissed about because he wanted to do it. The best thing about Cookie was that she was completely unpretentious and unaffected. I never saw her put on any kind of attitude, and she was willing to be friendly with everyone. A real sweetheart.

Glenn O’Brien, similarly, came up to me at some art opening and said he wanted to write about sports. I said, ‘Great, do it.’ I’d already known about Glenn because he’d published his TV Party Manifesto in the Eye, and had been the editor at Interview. Rudolf Piper [cofounder of the nightclub Danceteria] had a column as well. With many installments about his lurid experiences in Rio and the art scene there. David Wojnarowicz also came up to me at something and told me he’d like to write a column. I always liked David a lot. He did four columns. I wished he’d done more. A.I.D.S. didn’t stop him from writing for the Eye, but he’d gotten so involved with activism, and four installments of the column was all he was able to do. His was also some of the best writing we had in the paper.

I stopped publishing the Eye because I became physically exhausted to the point where I felt I could barely hold a pencil. I just couldn’t go on. And the Eye hadn’t gotten to the point where it could exist without me pushing it forward. I felt, a lot of the time, that it was a tremendous burden to keep it going. But I knew it was important. That’s why it went on as long as it did. After the Eye ended, I opened a club called Hotel Amazon. Before that, I had a club called Milky Way with Chuck Crook. RuPaul was the cashier for a little while. I didn’t know him personally. Sally Berg, the drummer in Information Society, was one of the door people, and she said, ‘This is RuPaul. He’s very honest. You can use him as the cashier.’ Sagittarians are supposedly good at first impressions. I was able to overcome my inhibitions and fears about other people and just say, ‘Go ahead, do it.’ And they did.”