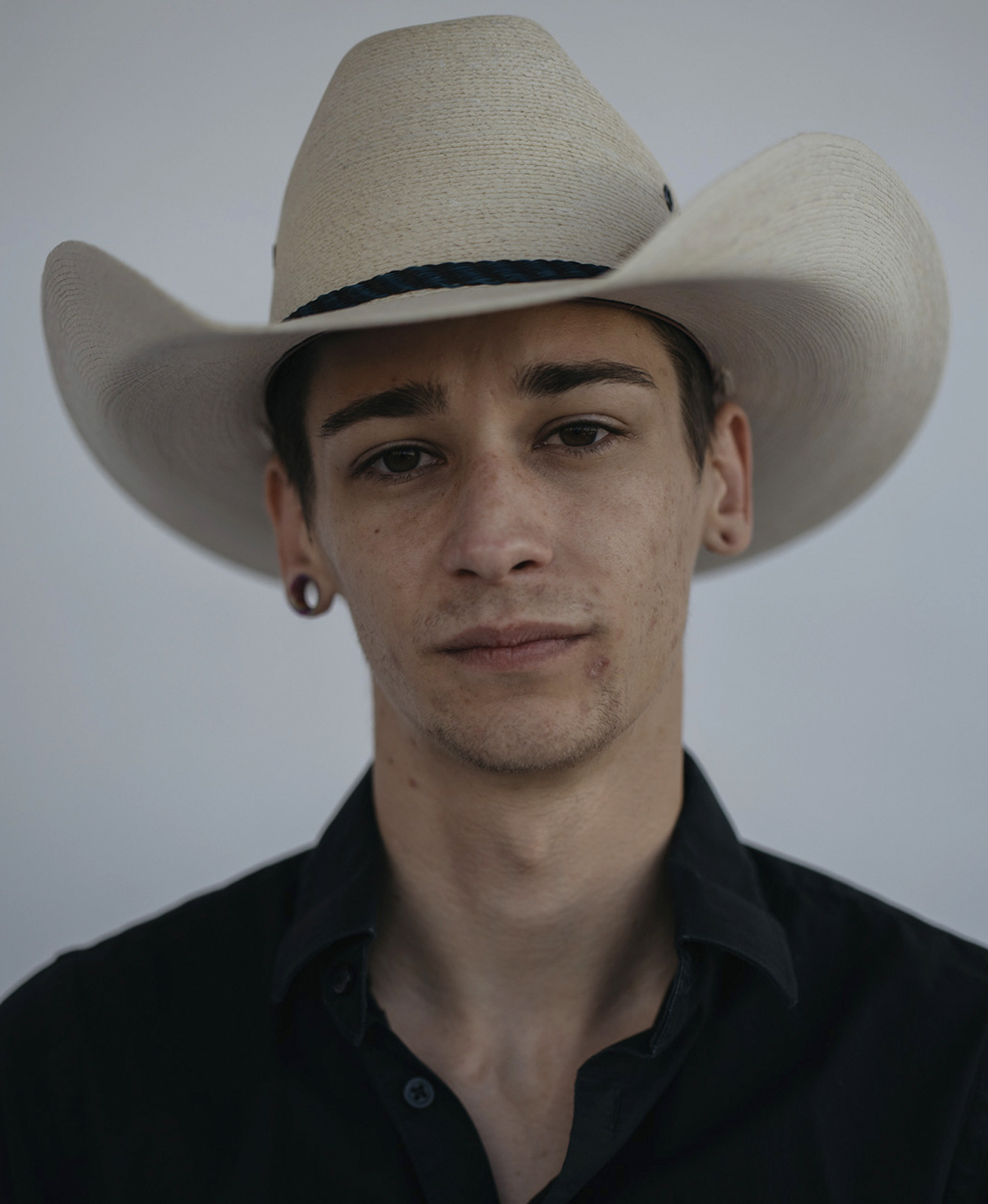

“The animal doesn’t care if I’m male or female, gay or straight. When I’m steer riding is the one time I can legitimately say I’m not going to be judged.”

Liberal versus bigot, urban versus rural, the coastal elites versus the flown-over: America today is a place of tribal dichotomies. Trump, we are told, has goaded even moderate Americans into taking sides and spitting feathers. Americans across the divide, we hear, are unable to engage in civil conversation. Apparently that’s not the case on the gay rodeo circuit, which—as well as traditional agricultural disciplines such as bull riding and barrel racing—incorporates such merriment as goat dressing, whereby pairs of contestants work together to put frilly knickers on a goat.

Nadine Hubbs, professor of Women’s Studies and Music at the University of Michigan, attended gay rodeos in heartland America while writing her book Rednecks, Queers, and Country Music. Talking over Skype, Hubbs tells me that, whereas mainstream rodeo seems a relatively hermetic insider sphere, “gay rodeo, on the other hand, connects queer people who have grown up inside that culture with outsiders who find themselves attracted to men or women in cowboy boots.” This also, she says, makes for a class-mixing arena that’s particularly unusual in modern day America, where social spaces have become extremely class-specific. “Upstairs-downstairs traffic—that’s always been hot terrain,” she tells me brightly. “Upper and middle-class people are often hot for working-class people and vice versa.” Noting that the cowboy has at times been a Republican mascot, Hubbs says, “Some of these people surely did vote for Trump. They may love what he’s doing as president even though they’re queer. But people at the gay rodeo are not flaunting their political buttons, whether they’re pro-Trump or con.”

Alina Whorez Cole is a 35-year-old lesbian military veteran who’s a fervent fundraiser for gay rodeo and has volunteered at events in several states, including her native Texas. A self-described country girl from a devoutly Pentecostal family, she says that “at the rodeo we’re so busy with safety and making sure that everyone’s okay, not just the contestants but also our animals. So the focus is less on what’s going on in the world and more on each other and our individual strengths. We really need that sense of community, and when you bring people from different factions and belief systems—when you bring them all together and you can have a positive event where everyone can be there for each other and love one another—I think it can really bring down some of the walls that are currently up in society.”

Speaking of walls, another characteristic of the gay rodeo is that it’s noticeably more ethnically diverse than the rodeo of the popular imagination. “Yes, there were lots of white rural folk,” Hubbs says of the crowds she observed in Chicago and St. Louis in particular, “but there were also African American attendees decked out in hats, boots, and Wrangler jeans, and also a lot of Latinos, including Mexican American folk from whom, let’s not forget, we get our words ‘ranch,’ ‘buckaroo,’ and even ‘rodeo.’”

“The animal doesn’t care if I’m male or female, gay or straight. When I’m steer riding is the one time I can legitimately say I’m not going to be judged.”

Such diversity is not intrinsically incompatible with the history of cowboying. William Loren Katz is a scholar of African-American history and the author of more than 40 books on the topic. In The Black West, he writes that “right after the Civil War, being a cowboy was one of the few jobs open to men of color who wanted to not serve as elevator operators or delivery boys or other similar occupations.”

I ask the musician and cowgirl Breana Knight about her experiences as a lesbian of color on the rodeo circuit. She says that if her white male contemporaries have a problem with her, they’re keeping it very well hidden. Of her own determination to defy stereotypes, she offers the following: “In this day and age I find it frustrating that people seem very committed to falling into the role that society has dictated for them, rather than challenging that role.” In any case, she reflects, “the animal doesn’t care if I’m male or female, gay or straight. When I’m steer riding is the one time I can legitimately say I’m not going to be judged.”

Except by PETA et al., that is. To say that animal welfare organizations and rodeo folk don’t see eye-to-eye would be a significant understatement. Organizations such as PETA regard the rodeo as inherently cruel, pointing to calves who’ve had their necks injured by lassos and the “frantic” goading of bucking broncos in holding pens. In response, rodeo advocates point to the enforcement of regulations that require, among other things, an on-site veterinarian at all rodeo events and the use of dull implements. “The gay rodeo takes considerable precautions and the animals are just as important as the participants,” says Knight. “The athletes and the animal are judged equally in bull riding, and stock contractors take incredible care of their animals. After all, if you’re not treating them well, they’re angry. And nobody wants that.”

It’s thought that the phenomenon of a specifically gay rodeo traces its roots back to Nevada in 1975, when a man named Phil Ragsdale was looking for an innovative way to raise money for his local senior citizens annual Thanksgiving Day feed. In holding an amateur gay rodeo on the Washoe County Fairgrounds, he established the circuit’s long tradition of charitable giving. Subsequent events benefited the Muscular Dystrophy Association. As Buck Beal, the public relations director of the World Gay Rodeo Finals, puts it: “It was felt that raising money [in this way] would make a statement for both our existence and our concern for our neighbors.”

The establishment of a national gay and lesbian rodeo circuit occurred in the years leading up to 1985, when the International Gay Rodeo Association [IGRA] was formed out of interactions between rodeo movements in Colorado, Texas, Arizona, Oklahoma, and California. At first, national meet-ups were secretive affairs, often picketed by right-wing Christians.

Wesley Givens became active in the Diamond State Rodeo Association in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1988 when the scene was still embryonic. “Attitudes were different back then,” he says, noting that 50 percent of members chose to be anonymous, identified only by a number in official records. These, he says, were known as “the silent members.” A decade later, after the proliferation of home internet, Givens became part of an AOL-hosted cowboy chat room that organized itself like a cyber ranch. “I was one of the ranchers and each of the ranchers would have a ranch husband,” he recalls. “One year all of us met up in Phoenix. The internet was kind of aesthetically challenged in those days, so it was all, ‘Oh you’re so much better looking in real life!’”

Technology evolved and within a couple of years Givens and his ranch family had migrated on to the website HomoRodeo.com, a nationwide social platform that exists to this day, organizing mixers and promising “general hootenanny” all over America. Givens says he took an extended break from the rodeo circuit during the course of his 15-year marriage, but returned to the fold after his husband ran off with a younger man. “I was brokenhearted, but the rodeo group really helped keep me going,” he says. At 57, Givens was recently photographed for HomoRodeo.com’s Cowboy Wanted calendar for 2018. “It’s for charity to help with the IGRA,” he explains. “It’s also nude.”

Anyone laboring under the apprehension that gay rodeo is some kind of whimsy should look no further than the index finger of Brian Helander’s left hand—or rather the absence thereof. In 1996, Helander’s first year of competing within the IGRA, an organization of which he would eventually become president, he overcame a traumatic amputation to win his very first prize buckle for chute dogging, a supposedly novice but nevertheless punishing event in which competitors must wrestle a steer, or castrated bull, to the ground. Despite the resulting digit deficit, Helander became hooked on the rodeo, and by 2012 he had received its ultimate accolade: “All-Around Cowboy.” A place in the IGRA’s hall of fame and the admiration of so-called buckle bunnies across the United States followed shortly—although he’s now happily married to a handsome doctor named Don.

Helander attributes his success in rodeo to an ethos that has crossed over into his professional and personal life. “It’s the cowboy attitude of just try,” he tells me. “We call it the cowboy try. Sure, you can’t jump onto the back of the horse and be an expert on day one. It’s going to take you two years, and it’s going to be an uncomfortable two years. Nowadays, I tell first-timers at the rodeo school that you’ve just got to get in there and make a start.”

Two more facts about Helander. The first is that he’s a Canadian cowboy, having grown up in Teulon, Manitoba, a small farming community an hour north of Winnipeg. “I am that shameful thing—a Canadian who doesn’t have a passion for playing hockey—so I had to leave,” he jokes. The second is that he’d never ridden a horse before his 40th birthday. As he told the Phoenix New Times in 2016, “The smell of the dirt, well, it just beckoned me to my roots. I knew right away. This is where I feel comfortable. This is where I can get dirty. This is where I can be me. In gay rodeo, I felt authentic.”

“The rodeo world is huge in America and the fact is, that world is closely tied to the Christian religion, and homosexuality just isn’t acceptable in that context.”

A question he gets asked with regularity is why a gay rodeo should need to exist in the age of marriage equality. Isn’t it retrograde and separatist? In response, Helander refers to his own experiences attending mainstream rodeos where the rodeo clown, the entertainer hired to provide comic relief between events, has made homophobic slurs part of his act. “The clown does some lispy, stereotypical impersonation of a gay person and the crowd roars with laughter and you think, ‘Oh my gosh, they’re ridiculing me in a roundabout way.’ When people tell me we don’t need gay rodeos anymore, I wholeheartedly disagree with them. It’s just not true.” That said, Helander notes that straight people are more than welcome to compete at IGRA events—and they do, in small, but significant, numbers. “We don’t make straight jokes in our arena,” he says. “The rodeo world is huge in America and the fact is, that world is closely tied to Christianity, and homosexuality just isn’t acceptable in that context. When it’s okay to be gay in Christianity, it will be okay to be gay in the rodeo world.”

The aforementioned Breana Knight grew up near the beach in Malibu, but even as a small child she would beg her bemused father to take her to the Forum in Los Angeles every summer when the rodeo came to town. She would go on to college at the nearby Pepperdine University, a conservative Church of Christ School, where homosexuality was taboo. “I had a girlfriend, but we had to hide our relationship for fear of expulsion. That was pretty stressful,” she recalls. Knight’s first glimpse of the gay rodeo was via a DVD she ordered from Netflix, a documentary called GidyUp! On the Rodeo Circuit, but the viewing experience was fraught. “I was terrified that someone would see me,” she recalls. “I was a hot mess at that point of my life.”

After a couple of years, Knight switched colleges and went to live in liberal Boulder, Colorado, where she felt able to come out. “People were like, ‘Oh, you’re gay, that’s awesome!’” she says. One night, at a party, she complimented a fellow guest on his cowboy boots. The man turned out to be a volunteer at the gay rodeo and offered to help Knight get involved. Her first ever steer ride, in Santa Fe, lasted 4.5 seconds—an astonishing achievement for a beginner. The moment was preserved for posterity on a 2014 episode of the CNN show This Is Life with Lisa Ling, which happened to be filming that day. Knight used the opportunity to come out to her mother for a second time—this time, as a cowgirl.

Camaraderie and community are two of the watchwords I hear time and again while interviewing gay rodeo participants. Knight, for example, recalls one event when fellow competitors held an impromptu whip-a-round to fund the graduate student’s onward travels, leaving the $400 she needed to get to San Francisco under her windshield wipers with a cheery note. “To be a part of this community is a phenomenal privilege,” says Knight. “I always refer to it as my rodeo family. If you do good by them, they’ll do good by you.”

Amid the country music dances and goat-dressing ex-uberance, a sobering feature of every gay rodeo on the circuit is a ceremony in which a riderless horse, its saddle bedecked with flowers or a ten-gallon hat, is led around the arena in memory of family members who’ve passed. At the 2015 gay rodeo in Oklahoma, the sound system failed during just such a ceremony, and an audience member spontaneously broke into the folk hymn Amazing Grace. “I don’t know who started that, but that was absolutely beautiful,” said the announcer over the PA system.

Brian Helander thinks that gay rodeo is still suffering from the aftermath of the A.I.D.S. crisis of the ’80s and ’90s. “That pandemic took away many cowboys,” he says. “We lost thousands and thousands, a critical mass of people who, if they’d lived, would be in their fifties now. They’d be the leaders and mentors bringing young people into rodeo, helping them ride a horse for the first time. It hit hard.” IGRA chapters, including those in Wyoming, Oregon, and Idaho, have had to dissolve.

Another threat is the internet. Ironically, the technology that enabled gay rodeo culture to spread like wildfire during its early days could also be its death knell. As Brian Helander says, “When you think back to 20 years ago, we didn’t have all the opportunities to connect on apps and social media. You had to go places to meet people. Nowadays, it seems you don’t have to do that, and I think it’s sad.” Nadine Hubbs thinks that, as with Amazon’s assault on concrete commerce, we may not know what we’ve got until it’s gone.

Over the years, gay rodeo has grown into a supportive network for hundreds of contestants and thousands of spectators. For those whose talents are aesthetic rather than agricultural, the circuit’s “royalty” tradition incorporates elements of the drag show and the beauty pageant. And crucially, whereas mainstream rodeo has traditionally been segregated by gender, in gay rodeo participants from across the gender spectrum are eligible to vie for prize money and a championship buckle in any event.

Fundraising for causes, including H.I.V. and A.I.D.S. charities, remains integral to gay rodeo and is typically effectuated by the glamorous denizens of the royalty wing. One such self-described “cash cow” is Alina Whorez Cole. Having moved away from her disapproving Pentecostal family in East Texas, she decided to volunteer at the Denver gay rodeo last July after her teenage son came out as gay. “I wanted to ensure that the organizations that help the community are around when my son is older, so that he would have somewhere to go to be loved and accepted, and wouldn’t have to live like I have,” she tells me. Since Denver, Whorez Cole has been all over the United States raising money. In royalty, she says, “our entire lives revolve around promoting the western lifestyle and bringing new people in who’ve never experienced it.” Noblesse oblige.

By day, Brendon Dale is an independent hairdresser working out of Fort Worth, Texas, who does “vivid, obnoxious” dye jobs for the town’s service personnel. In royalty, he’s a “singing drag queen by the name of Sha Tinkled” whose signature number is Girl Crush by the band Little Big Town. A tale of sublimated, unrequited love for an alpha male, it’s especially poignant when sung by a young man in a dress. The meaning of gay rodeo for him? “We should live our lives happy and stop dividing our community and country,” he says.

On the face of it, all this may seem like a world away from traditional rodeo, a dusty cauldron of testosterone that’s surely as heteronormative as any college football stadium. It’s no coincidence that Ronald Reagan adopted the public image of a straight-shootin’ cowboy to appeal to an America whose confidence had been decimated by scandal and the Vietnam War. That appeal to frontier masculinity was almost certainly a defining factor in his first successful bid for the presidency in 1980.

The 19th century archetypes that inform our modern conception of the cowboy’s world are arguably less binary than we’ve been led to believe. In his book Queer Cowboys, the author Chris Packard considers, through his examination of books by legendary western writers such as Mark Twain, how same-sex intimacy and homoerotic admiration were key aspects of western tales long before the word “homosexual” was even invented. Today, he writes, our movie-born images of cowboys epitomize the strong, silent type, but “if you look a little closer at this image, you’ll see another figure, the cowboy’s sidekick—his partner and loyal friend.” Barely disguised erotic affection, he says, is the scaffolding that underpins their friendship. And haven’t cowboys—the original “gig economy” itinerants—always lived outside the conventions of the traditional family unit?

Equally, for those in possession of two “X” chromosomes, the inhospitable West has long been a subculture in which athleticism, skill, competitiveness, and grit have been acceptable, even desirable, traits in women. Women, writes Mary Lou LeCompte in her social science book Cowgirls of the Rodeo: Pioneer Professional Athletes, were “largely unencumbered by Victorian middle-class notions of womanhood.” Consequently, their self-image and sense of “being a lady” was never at odds with their athletic skills and ambitions.

Certainly, for those who continue to participate and attend, the gay rodeo offers a bracing vision of queer rural life that’s a world away from the bleak portrayal of Brokeback Mountain. Here is an alternative frontier. One which, though hard-won and highly demanding, is rewarding and supportive like no other. Or, as Wes Givens, aka Mr. July 2018, puts it, “Now I can flip a steer or kiss a man. Both are easy.”