Josiah Wise's latest release as serpentwithfeet is a sensuous plea to indulge the fantasies of unbroken human intimacy.

It’s been less than two years since Josiah Wise tacked his interior world onto the walls of the internet with blisters, a five-song collection released under the name serpentwithfeet. In a little over twenty minutes of music, Wise presented a spectrum of sounds and experiences, all urged on by the cool trill of his voice, an expanse of emotions more a product of the world-weary than a 27-year-old living in Brooklyn.

Wise’s ability to gather the emotional knowledge carried by himself and others, and transforming it into sentiment and song, has only deepened in the time since. His latest release, soil, is the continuation of a locked stare. It’s a stare that follows the eyes of a fantasy, one composed of surrogate lovers, physical forms, the tactile truths of rivers, plants, skies, the soil on which any dream stretches out upon. There is an alluvial sexuality that hangs on to Wise’s every quivering syllable. It is the fragrance emitted from each of soil’s 11 tracks. A sonic sparseness is one of his many diminutive gestures, capitalization included, that feels like an act of generosity to the listener. It’s a reprieve, really. In Wise’s performances, and throughout soil, the opacity of the performative ego is replaced instead with a transparent voice with a plea to indulge one’s own fantasies. It’s devotional music that knows no physical or conceptual boundaries. The adoration relayed in songs of worship (it’s well-noted that Wise first learned to sing in church, which he attended until the age of 21) are fused with the lyrical reverie of Kate Bush and the blunt love offered by groups like TLC or Destiny’s Child, two of his favorite acts.

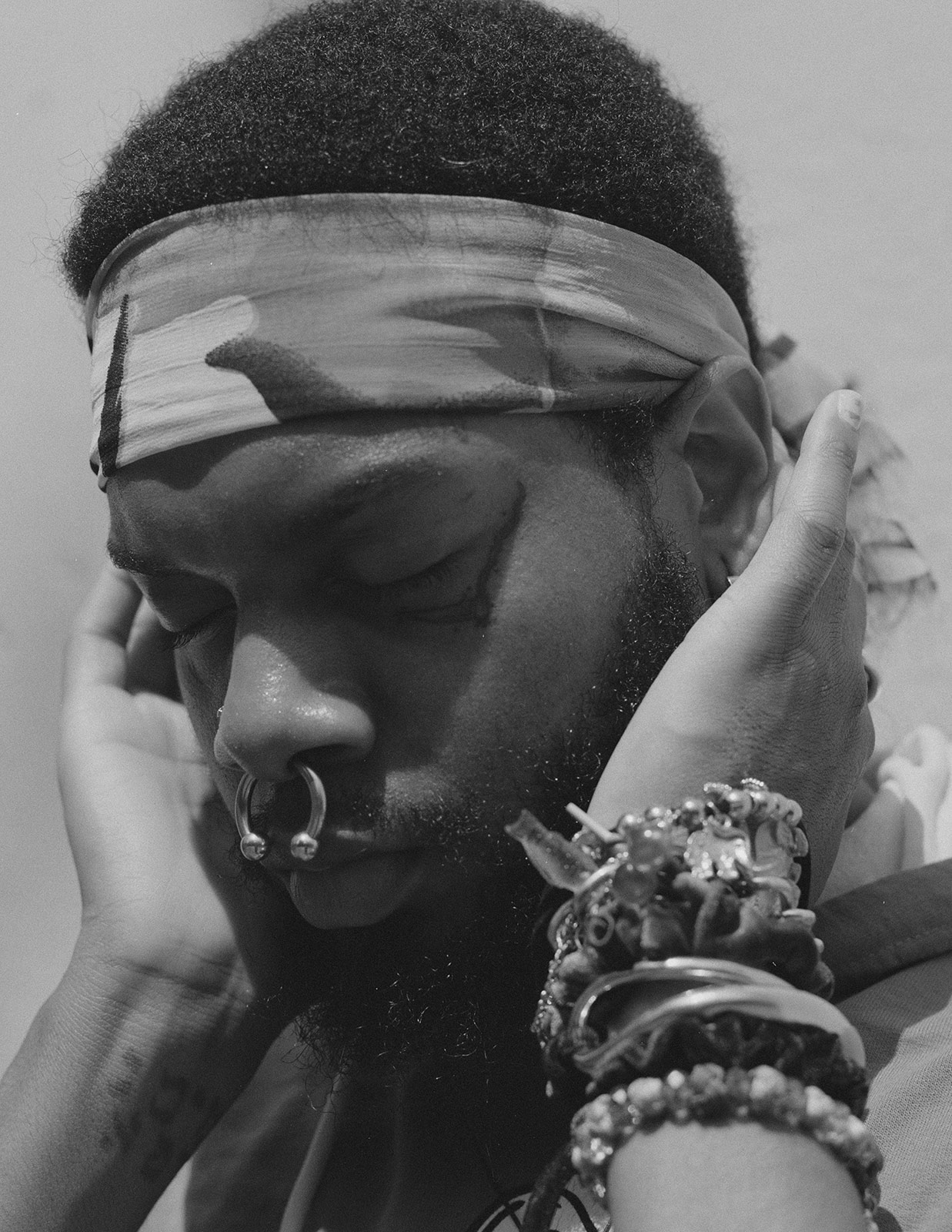

On a warm Saturday this past May, Document spoke with Wise on a handball court in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene neighborhood. Wearing an outfit featuring a purple and orange motif—orange headband, purple pom-pom dangling from his left pocket, orange necklaces—he introduced himself as ‘serpent’ and quietly uncoiled the labor of his creative process, of being a black, gay man. For Wise, it’s a moment of optimism and heretofore unimaginable connection, a time where marginalized voices are writing a new lexicon for the world they wish to inhabit. Someone after all, he tells Document, has to do the work.

Document—I’m curious about your experience singing in church, learning to use your voice in the choir, and breaking free of that to write your own music. How much of a change was it to move from religious music with a very clear message to creating your own music?

serpentwithfeet—Gospel music is love music. It’s still sensuous. I think a lot about what it is to honor someone’s story, be it in a painting or sculpture, a documentary, a film. You’re honoring the truth in honoring someone’s story, the truth of the story. I don’t think it’s different if you’re talking about a lover or sex or a plant, you’re still taking time to honor something.

Document—Is there any meaningful difference, then, between the message of a worship song and, say, a love song?

serpentwithfeet—The subject of the story is maybe different than a Destiny’s Child song, but it’s still talking about an experience with another person. We learn so much about the climate of moment listening to these songs, not just the person. If you listen to Destiny’s Child, you’re not just thinking about their opinions on love, you’re thinking about the climate. We’re coming out of a period, still in one actually, where men were heavily misogynist. Where women were pressured, specifically black women, to be shaped a certain way, and have their hair a certain style, and to constantly be “on.” I think the way people talk about their relationships says a lot about the world. The way people talk about love now, as opposed to 60 years ago, is very different. Destiny’s Child wrote love songs, but they spoke to an environment. I think about how many guys did not like TLC’s No Scrubs or when Nicki Minaj released Lookin Ass and people didn’t like it. It speaks against our experience with men, and it says a lot about the climate.

Document—What climate would you say soil is a response to or a product of?

serpentwithfeet—It’s too hard to say, really. I’m too close to it. But what I would say is we’re in a time where gay love doesn’t have to be marginal love—black gay love doesn’t have to be marginal. We have Moonlight. We have Noah’s Ark. We have Kevin Abstract from Brockhampton. We have Frank Ocean. We’re talking about disrupting gender roles, this is a thing now. And then there’s the internet. My project has to do with ventilation.

Document—Ventilation?

serpentwithfeet—I think if I had a new album ten years ago, I’d be a lot freer with my words, with how I use my words, but things have changed. It’s not a read. The internet didn’t exist in 2008 like it does now; it’s a big network, a community. If you know how to use it, you can have a community that spans from Greece to Austria and Venezuela, and its not a reach. It’s a lot more difficult to oppress people when we have that kind of access. I could go on a whole other spiral…

Document—You can spiral if you want.

serpentwithfeet—No, I’m not going to. [Laughs] It’s beautiful to see conversations about queerness, trans-ness, blackness, and fluidness. It’s not just happening in New York. It’s not just happening in Los Angeles. It’s happening everywhere. It’s the standard now, to the point where even my family has to think about it. That’s not their world. I used to think it was just the art world, but its not. It’s a big conversation, and almost everyone has to be accountable—a lot more people than ten years ago, at least. If you are using unfavorable language, you’re more likely to get shat on now. More people are gonna clock you. You need to be a good steward of your words. It can end, or start, your career. The little joke you made can be a big deal. It might be terrifying for some, but I think about micro-aggressions for someone who’s been oppressed, how often the oppressed have been forced to be aware of themselves. You know when someone is not feeling you. The little things. Those things that used to pass can’t pass anymore.

“There’s an importance in complaints. There’s an importance in complaining with a gravitas.”

Document—There’s a language, or an attempt to develop language, where there once wasn’t.

serpentwithfeet—soil is me having more language and also me having a bit more courage to say things in a way I didn’t have the courage to say them before. I didn’t have the language. It’s a complete reflection of the time, where I am now able to talk about my experiences with men in a very pointed way. It’s reflective of the time I find myself in.

Document—A common response is that this is trivial or petty, that this new language is the product of some knee-jerk liberalism that’s out of touch when, for others, it’s life-affirming.

serpentwithfeet—I think most people think new ideas are petty. Take the internet, again. There’s all the bullshit I hear people talk about: no one is having conversations anymore. It’s not true—we’re talking more than ever and to a lot of different people. There is a woman I know from social media for years, who now does my makeup when I play shows in London. Having this access, I think it can be scary to some people. And with language, there are people who don’t like how specific we’re getting about pronoun usage, colorism, misogyny, sexism, ageism or sizeism. For some, you didn’t have to think about or talk about any of this depending on how much privilege you have. People now have a voice more than before. If you have a Twitter account, you have a voice more than ever before. We see that. Some people don’t want to do the work. Me? I’m a black gay man, and I’m always talking about race. I came out the womb talking about race and colorism. If you don’t want to hear it, well, that’s your privilege. White people don’t think everything is about race. As a black person I know everything is about race. I know that. [Laughs]

Document—How do you handle the question of which voices get to say what? There are compelling arguments for and against essentialism, who has the right to address certain grievances, issues, parts of culture.

serpentwithfeet—There’s not an oppression Olympics, but I don’t get how a white person, say, who grew up in upstate New York from a line of wealth can complain about not getting their first choice of job. You cannot compare that to a black person that deals with generational incarceration—can’t compare it. I think that is a tough pill for people to swallow. Everybody wants to complain and have their moment. A few years ago I had mine with an injury.

Document—What happened?

serpentwithfeet—I fractured my heel. I had crutches and a cast up to my knee, and it was summertime. It was one of the worst times of my life, and I had to leave New York. This city is brutal if you’re not able-bodied. I never had to think about it before. I realized, “Oh, shit, this is my privilege.” I never once had to think about people who have physical injuries or the elderly, what they have to deal with. And to bring that back to soil, there’s an importance in complaints. There’s an importance in complaining with gravitas.

Document—Is there a dominant tenor to these complaints? Something freeing to you in the act of airing grievances?

serpentwithfeet—Thinking about who the land was taken from, who built the land, who built pop culture from music to dance, there’s always been a resistance. These aren’t empty grievances. But now, it’s bleeding into people’s romantic lives, their family lives. We are just now understanding that we don’t have to keep uplifting the thing that is toxic. I don’t have to uplift the thing that restricts breath. I don’t have to uplift the thing that kills me. That’s happening now. Abuse in their relationships. How they’re being treated on Tinder or Grinder. And, it’s being taken seriously. That is what’s so exciting: Everybody is swiping left now in their life. Nope. Nope. Nope. I don’t want that. I think that’s really beautiful.

“We’re are just now understanding that we don’t have to keep uplifting the thing that is toxic. I don’t have to uplift the thing that restricts breath. I don’t have to uplift the thing that kills me.”

Document—There’s attentiveness to your music. It’s ornate, but not ornamental; every small stroke seems to conspire to be part of some larger sentiment. Where did you tap into this?

serpentwithfeet—I grew up not ever seeing attentive men, but in recent years, I’ve met a lot of wondrous, attentive black men who are alert, agile, full, and expansive people. It forced me to reappraise how I thought about myself. A lot of my self care I learned from black women, just seeing how my mother takes care of herself. She perforates her day with reading. I’d knock on the door to her room, and she’d always be reading. For her, that was a form of nourishment. That’s a big thing for me now, taking more time to read and feel myself. My black women friends, and my mom, they always seemed to see more than I could see. They could read situations in a way I couldn’t read them. It made me want to observe things more, and to be accountable for what I was observing. In a very explicit way, that’s what every song on soil is really about; trying to observe myself, even in a fictitious way, and trying to be so in the story that I’m lucid dreaming.

Document—Can you point to a particular moment of this on soil?

serpentwithfeet—In Fragrance, I talk about contacting my ex-boyfriend’s ex-boyfriends because I want to know if he’s affected them the same way he’s affected me. I say, “I imagine us singing his name in harmony. I imagine it sounding good. I imagine me kissing your ex-boyfriends wondering if they still taste like you.” I tried to be soaked in that vision, wondering what it felt like, what it tasted like, what it smelled like. My favorite writer is Toni Morrison. Her fiction is so sensuous. There’s so much sensory detail. I like that she can be so in this moment that happened in her mind. That’s a particular power.

Document—Who do you consider to be your audience for these fantasies?

serpentwithfeet—Well, Spotify actually revealed it to me. I was surprised. I have a large male audience.

Document—Why is that a surprise to you?

serpentwithfeet—That’s the thing, maybe I shouldn’t be surprised. Why wouldn’t guys listen to my music? Why would I think they don’t have the patience. Who said that? No man has come to me and said, “This is a girl’s song.” Men have to build a culture for other men to have emotional real estate—real estate to be vulnerable and transparent.

Document—How do they respond to your work? Do any particular encounters stand out?

serpentwithfeet—I don’t know if there’s a specific one, but it’s typically that these men felt that my words, delivery, and treatment of grief…they generally respond with a sense that I handled it well, that it was a warm recounting of my experiences. I never want to exploit my experiences. I never want my performances to feel like a cheap therapy session. I’m not looking for my audience to be the recipient of my things—things I didn’t deal with. I don’t want people to feel burdened after they leave a show or hear the album. But, I don’t want to avoid difficult things. I want it to feel like I’ve processed my experiences, and I’ve done my own work.