Known for work that takes place on a captivating scale, the painter discusses a technique that operates far beyond the realm of one dimension for Document's SS 2018 issue.

Since the late 1990s, the German painter Katharina Grosse has worked almost exclusively with industrial spray guns, applying vivid swaths of acrylic paint to abandoned buildings, mounds of dirt, and museum walls. Whereas painting once depicted the world, she applies paint to the world itself, and the results are often spectacular and kaleidoscopic installations that blend painting, architecture, and land art.

Grosse attended art school during the 1980s in Düsseldorf, where faculty included the renowned painter and photographer Gerhard Richter and the “father” of video art, Nam June Paik. While many of her peers, like Andreas Gursky, were drawn to photography and new media amid renewed pronouncements of the “death of painting,” she bravely explored the potential of the centuries-old medium, using a vigorous pictorial language defined by and through color.

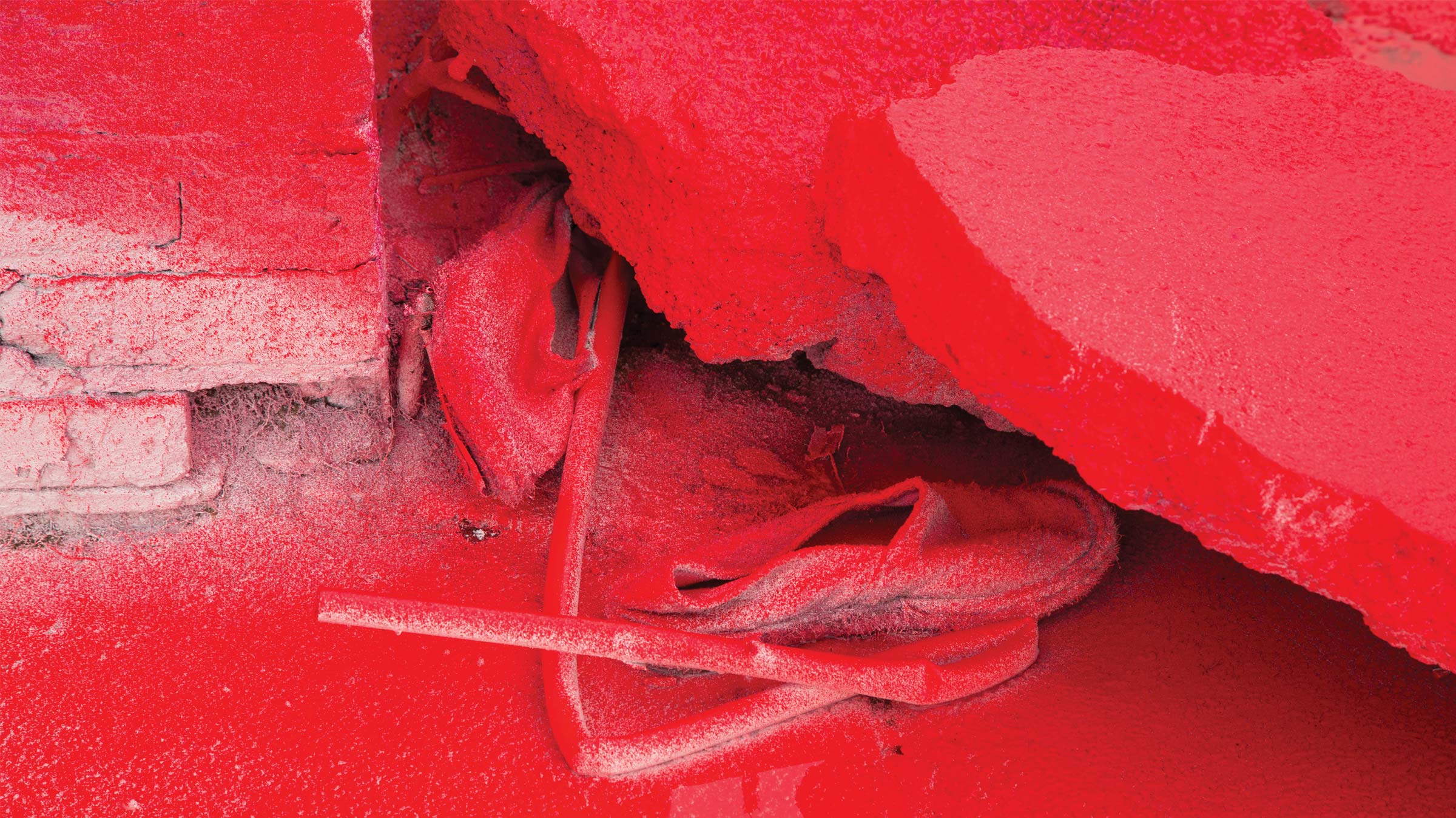

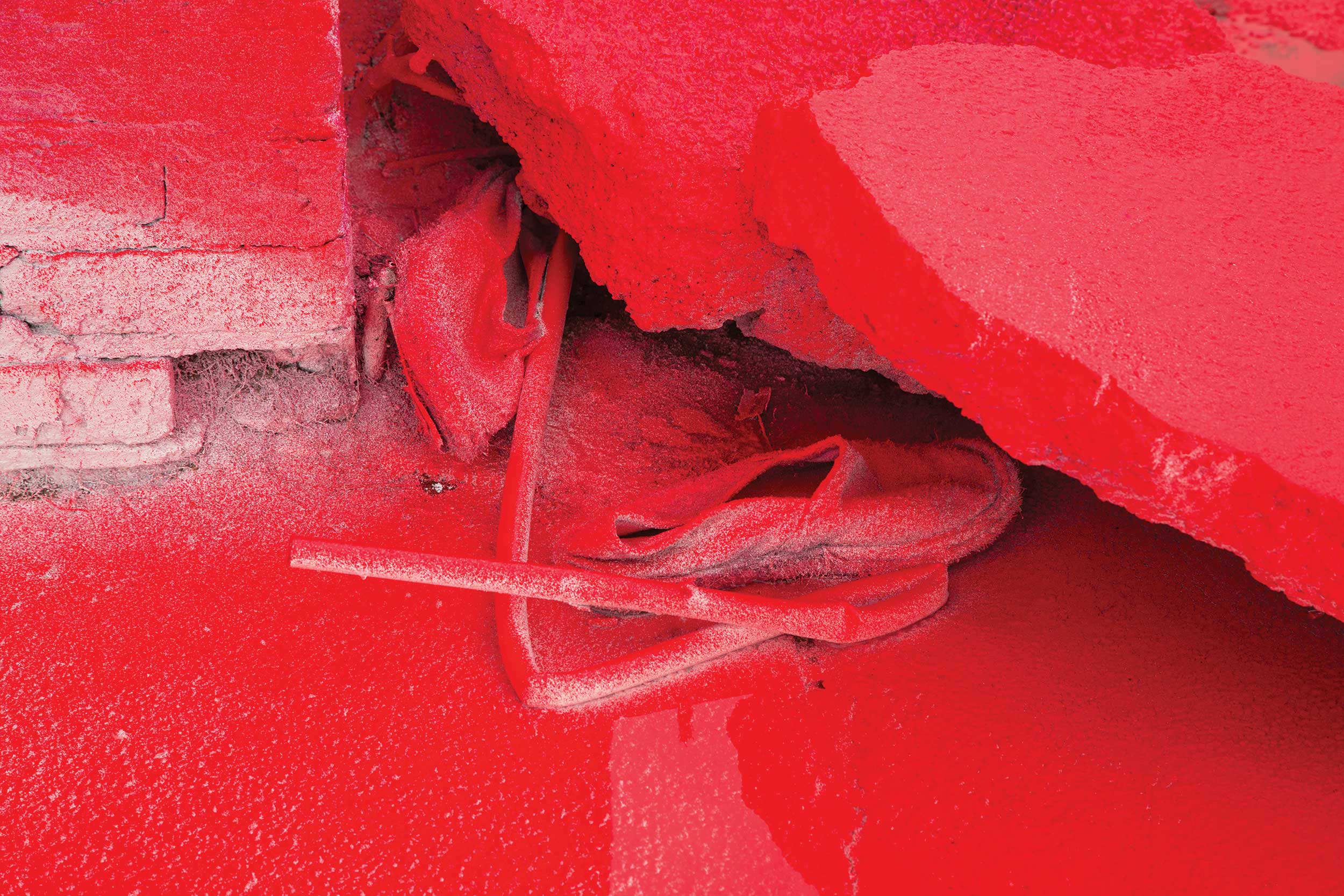

Over the last several decades, Grosse has exhibited works all over the world, from MASS MoCA in Massachusetts to the Palais de Tokyo in Paris and the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow. In 2018 she has already produced three large-scale site-specific works: The Horse Trotted Another Couple of Metres, Then It Stopped at Sydney’s Carriageworks, Ingres Wood at Rome’s Villa Medici, and Wunderbild at the National Gallery in Prague. The exclusive portfolio of images featured on the following pages was taken by the artist herself, and provides a unique glimpse at the artist’s own view of her work and process. Drew Sawyer caught up with Grosse shortly after the opening of her ambitious new works to chat about her practice.

Drew Sawyer—You’ve already had such a busy start to 2018, with three major site-specific works. I was looking at the installation shots last night and was amazed how the works look so different, and I think it speaks to how you really respond to space. How did the architecture impact your approach to making each work?

Katharina Grosse—Carriageworks in Sydney was particularly interesting because I had a lot of volume to work with, but the walls and the floor were historically listed. I was thinking I could use fabric to create my own space, and the fabric would be visible and exciting to look at from both sides. At the same time, the specific architecture of Carriageworks would still be visible, with the light coming from above and with the columns that are such a dominant part of the structure.

Drew—It does seem like a lot of fabric!

Katharina—Yeah! [Laughs]

Drew—So the fact that this space didn’t have walls forced you to think about using fabric or approaching the site in a different way.

Katharina—I think the question that I have is: How can a painting appear in a given situation? How could it be made visible? It is not a given that you have a surface, then you paint, then you put it somewhere. I think a painting is something very mobile, actually very independent from space. It can appear anywhere, and I just have to manipulate the situation a little bit, then I can have a surface on which I can have something painted. That’s my approach.

Drew—From the installation shots, the space looks extremely large. Is it one of the larger spaces you have installed your work in?

Katharina—It is very large. It’s not only that it is big, but it also has so many little details and folds. So once you’re in, you start to really look at what you see, and then this idea of, ‘Oh, this is really big’ disappears. Looking at the photographs, the first thing you think is, ‘Oh, that’s large.’ But then once you’re in it, you move in it. If you move in a forest or a garden, you don’t constantly think you’re small. You’re relating to other things that are smaller than you.

Drew—Right, and I think that’s something that’s so nice about this portfolio of images for Document. One gets these close-up views, even behind the paintings, views that maybe you get as a viewer, but not from installation images of your work.

Katharina—Yeah, they are more about looking at something or discovering something that is part of a really more complex work. It is not about documenting a large work, in terms of artistry or contemporary art. If you want to know about the work you could google it. But these kind of shots you would never find online.

“There is no consecutive, one-after-the-other, linear movement in painting. Painting is more like a cluster. The thing you paint first and the thing you paint last are all on the canvas at the same time.”

Drew—I was going to ask this later, but this point makes me think about how you went to art school in Düsseldorf at a time when photography really came to the fore, in that renowned program and in contemporary art more generally. I’m curious if photography has been important to you. Have installation images made you think differently about your work?

Katharina—That’s a lot of really good questions you’re putting into one. I had a lot to do with photography when I was studying in Düsseldorf because it was that time in the ’90s when Benjamin Buchloh came back again with the sentence that Rodchenko already had said—that painting is dead. I also worked with video a lot, but it made me come back to painting because I discovered that painting has a really unique understanding of time. There is no consecutive, one-after-the-other, linear movement in painting. Painting is more like a cluster. The thing you paint first and the thing you paint last are all on the canvas at the same time. So you could also reverse your understanding of the present, future, and past. Also, my body intelligence responded better to a tactile surface. I think that we have so much imagery in our lives that comes from homogeneous surfaces—from the screen, from photography, from our phones. That’s a lot of really good things for us, but I think that the tactile image or multilayered images like painting provide a different kind of knowledge. Maybe more authentic as well. Therefore, I like uneven surfaces, the folds or sometimes sculptural surfaces of soil or trees, or even making other parts of the building part of the work.

Drew—Do the soil and the trees usually come from the sites themselves?

Katharina—Yes, they are from the sites. At the Villa Medici there was a very specific tree that came from the garden that inserted a special story into the work. This pine tree was planted by Dominique Ingres, the famous French painter who was once upon a time the director of the Villa. But the work transforms the tree, gives it a different function. I also like that the image of the tree or soil is already very strong. It’s this kind of primordial relationship. You have certain materials like soil, wood, a book, your bed, or a house. They are all primordial signifiers, in a sense, that I use for my work.

Drew—Do you often think about or try to engage with the histories of the specific sites, like Ingres planting a tree, or are you more interested in responding to the present architecture?

Katharina—It is always a crossover of the interests I have in that moment. The Villa Medici has such a strong historic framework, not only in the villa but also in relationship to the urban fabric of Rome. I had to wonder what I could do that would really set my work apart from all these other works of art that are around it. In Prague it was a similar situation. It was an old trade fair building, with a very industrial atmosphere. How do you establish a work in that huge space? All the three different spaces and situations had a certain demand because of the historical background, but at the same time they prepared me for something I hadn’t done before and I was eager to try out.

Drew—Yeah, I was going to say that the Prague installation, in particular, seems different from your other works, or at least other works that I’ve seen you do.

Katharina—Yes, I was very excited about this installation. I saw the show that Ai Wei Wei had there. He had inflated this big raft and other things. It was a really interesting way to fill volume, just with air, which was very clever. You had to be very intelligent, in a sense, to tackle that volume and not fill it with just tons and tons of stuff. I thought I’d do exactly the opposite of filling it, maybe just go towards the skin of the place and invent another soft skin and camouflage the architecture and manipulate the walls by actually putting something in front of them that didn’t touch the walls. My work is actually away from the walls, like two meters, nearly. It’s the first time, you’re right, that I’m using quite organized structures on the painted surfaces that I’m making part of the work. I also didn’t paint it on site. I made it in my studio.

Drew—That’s interesting. I was going to ask you about this sort of relationship between these wall or in situ works that you’ve now been doing since the late’90s and your continued studio practice. The Prague installation seems like a synthesis, more so than the other ones.

Katharina—Yes, very much so. I think there are such different modes of working, different formats. When I’m in the studio I can come back to the paintings over a longer period of time. It’s more like compressing thoughts and energies and movements that you’ve had. I actually take something apart and make it larger and slower and more accessible. It’s more like expanding rather than compressing. Those are two very different perspectives. It’s a little bit like you’re swimming. You can either swim in the pool or in the sea.

Drew—Obviously, what unites all your work is color. I’m curious if you could talk a little about what color means to you, how you perceive color, what it does for you, and also for the viewer?

Katharina—I think color is very independent from sight or from objects. There’s no reason why you would say this color has to belong to that object. It can appear anywhere. It has different functions and evokes different things wherever it is. You can’t measure it like you can measure from here to that next chair. You can say that’s five meters, but you can’t measure how deep blue is. So I think it is very much linked to your imagination. Making a painted image is like the perfect threshold that belongs both to what we call reality and what we call the imaginative world. I think a painting is like a membrane between these two things. For example, we can imagine things, yet at the same time be on a bicycle and ride down the street. Which seems paradoxical because you can imagine to be somewhere totally different, and yet you perform something in the so-called real world. I think color has the ability to be either/or at the same time.

“All the three different spaces and situations had a certain demand because of the historical background, but at the same time they prepared me for something I hadn’t done before.”

Drew—Obviously color is extremely subjective, as you were saying. Do you hope to somewhat control how visitors experience your work? Are we entering into your subjectivity?

Katharina—There has to be a certain amount of accessibility to your subjectivity so that it can connect to other people’s thinking. Otherwise, you’re having a private experience but it doesn’t communicate. So the work has to be open so that other people can dock onto it. That kind of openness or unfinishedness or readiness to be connected with, I absolutely have to have that in mind when I work.

Drew—So you’re really just leaving it open.

Katharina—I think there are certain things I do on purpose, like the excess of it, the absurdity of the scale, the idea and feeling of a certain freedom you might experience when you see it. Or that you are seeing something you can’t see anywhere else. It’s a unique experience then. I think it’s my task to propose images, painted images, that could make a proposal for how we can expand our imagination. That’s what artists do, we make proposals to expand the imagination so that we are all able to find better solutions, more flexible solutions, for things that we want to do or decide upon. That’s my way of contributing towards the necessity of creating a space where you can imagine something that you would not be able to imagine otherwise.