The Palestinian-American artist discusses the cultural weft of his evocative handmade embroidery—featured, this weekend, in Frame at Frieze New York.

Jordan Nassar is a Palestinian-American artist who has decided to engage with the ever complex layering of global communities and customs with work that is, itself, a complex laying of color, composition, landscape, identity, and experience. Practiced in the art of traditional Palestinian embroidery techniques, Nassar creates visionary, even utopian, landscapes. His work speaks to our collective hopes for a better future, presenting it humbly and directly through the small scale of his creations. His hand-crafted pieces manage to be both politically charged and optimistic, qualities of equal importance in times of tumult. Born and raised in New York City, Nassar’s work is a dialogue on longing—one set against the backdrop of the Palestinian diaspora—for a peaceful resolution to difficult conditions in the Middle East. He is married to an Israeli, and so this resolution is often portrayed across his work in open, embracing terms. Recently, Nassar’s work has been featured prominently in exhibitions such as Long, Winding Journeys: Contemporary Art and the Islamic Tradition at the Katonah Museum of Art, and a solo presentation at this year’s Frieze New York in the Frame section. The artist spoke with Document ahead of the art fair about his cultural displacement, hopes for unity, and earning the esteem of Palestine’s weavers, women who were frequently shocked to see a man practicing their cultural craft with such skill.

Document—Given the abstracted scenes you build out of color, pattern, and shape, can you walk us through the layers of meaning your work aspires to evoke?

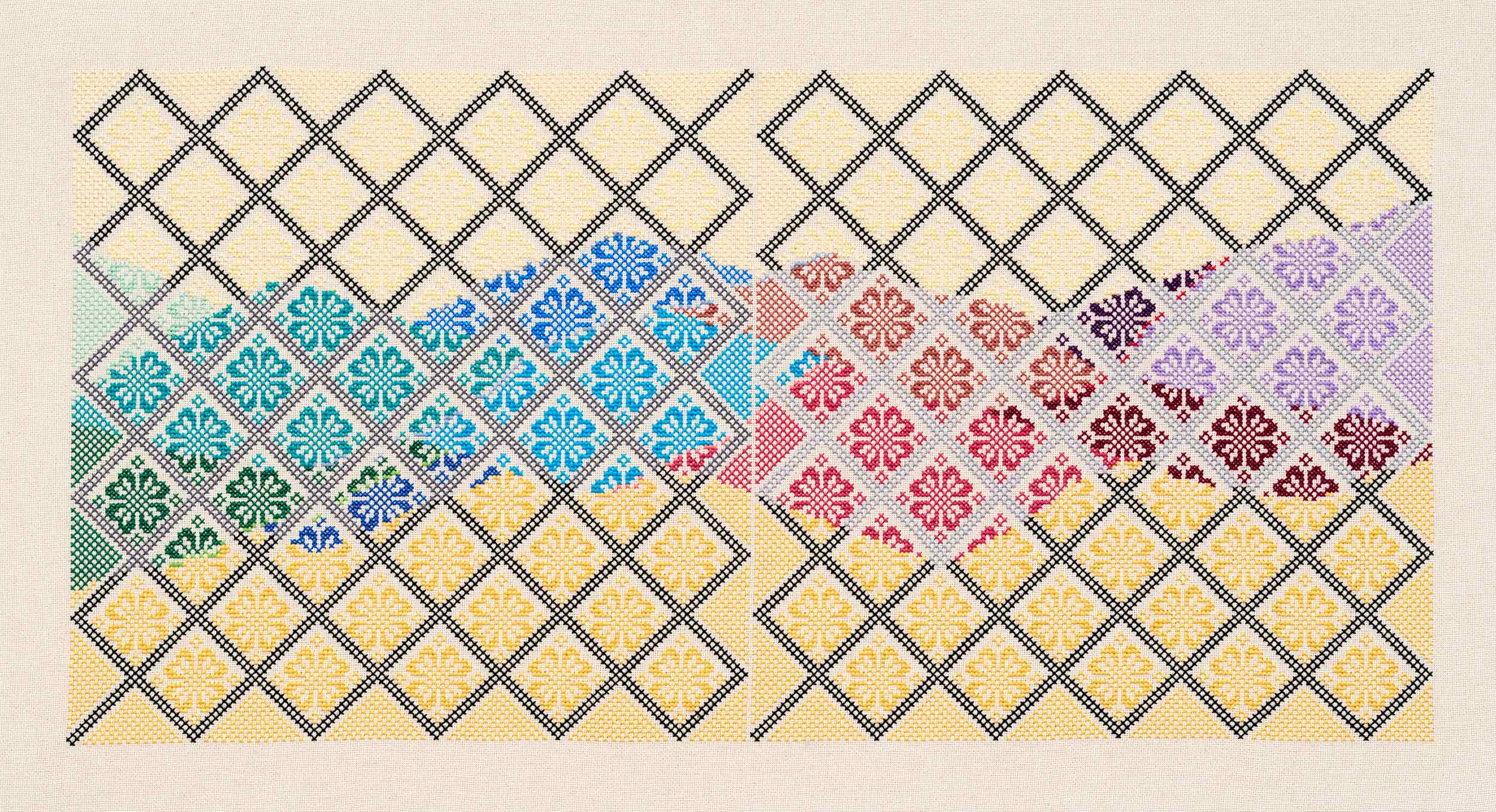

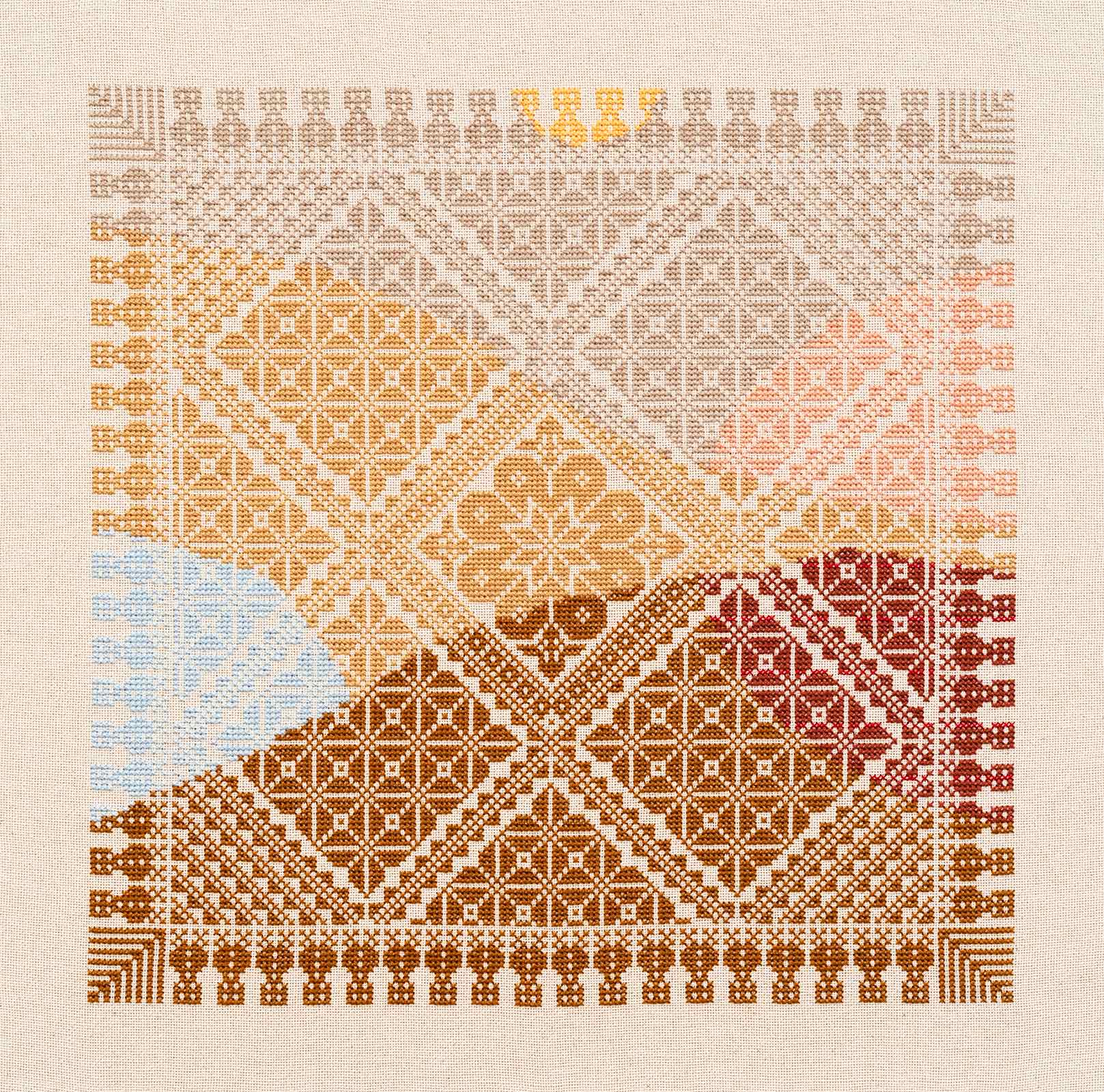

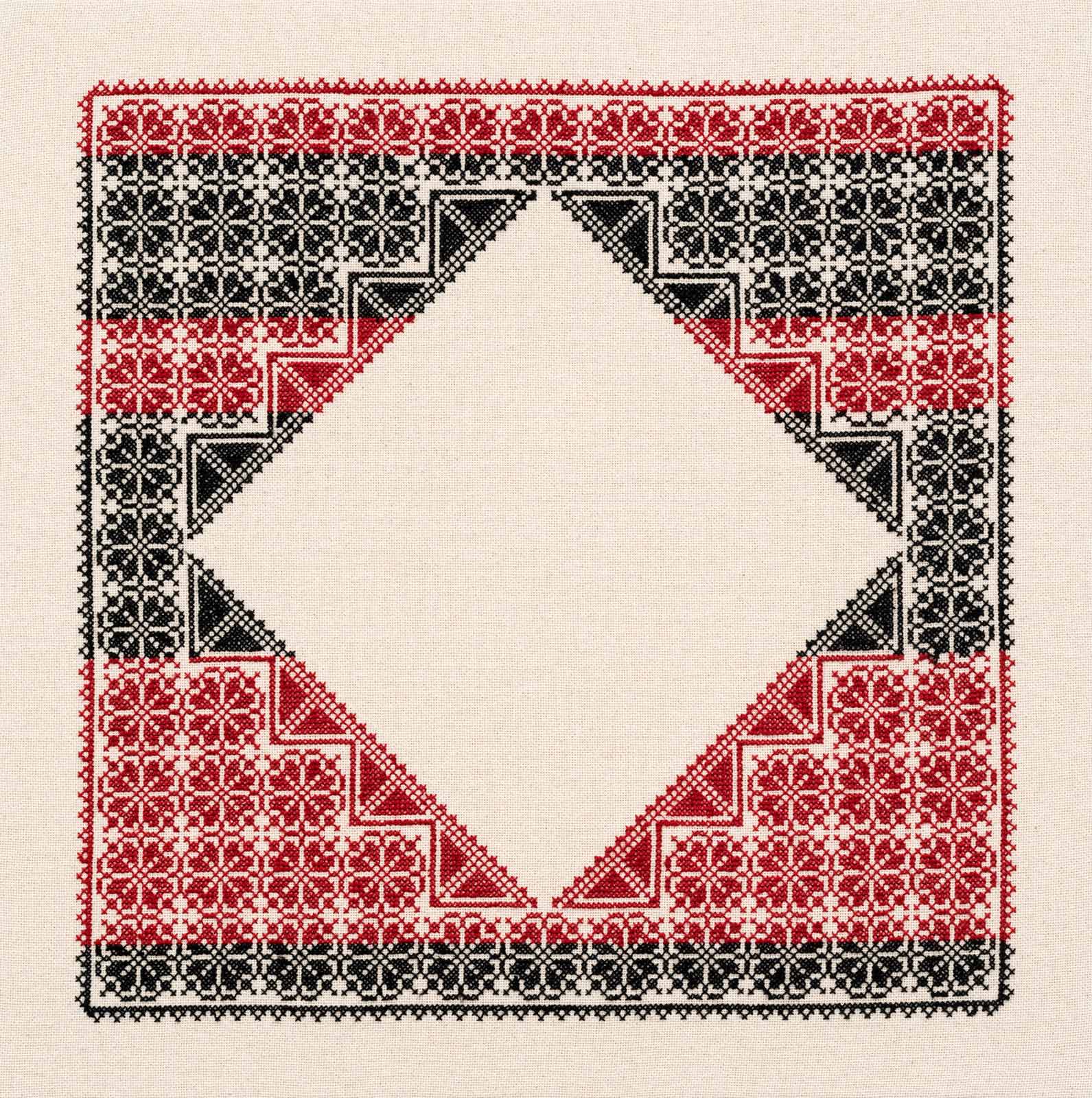

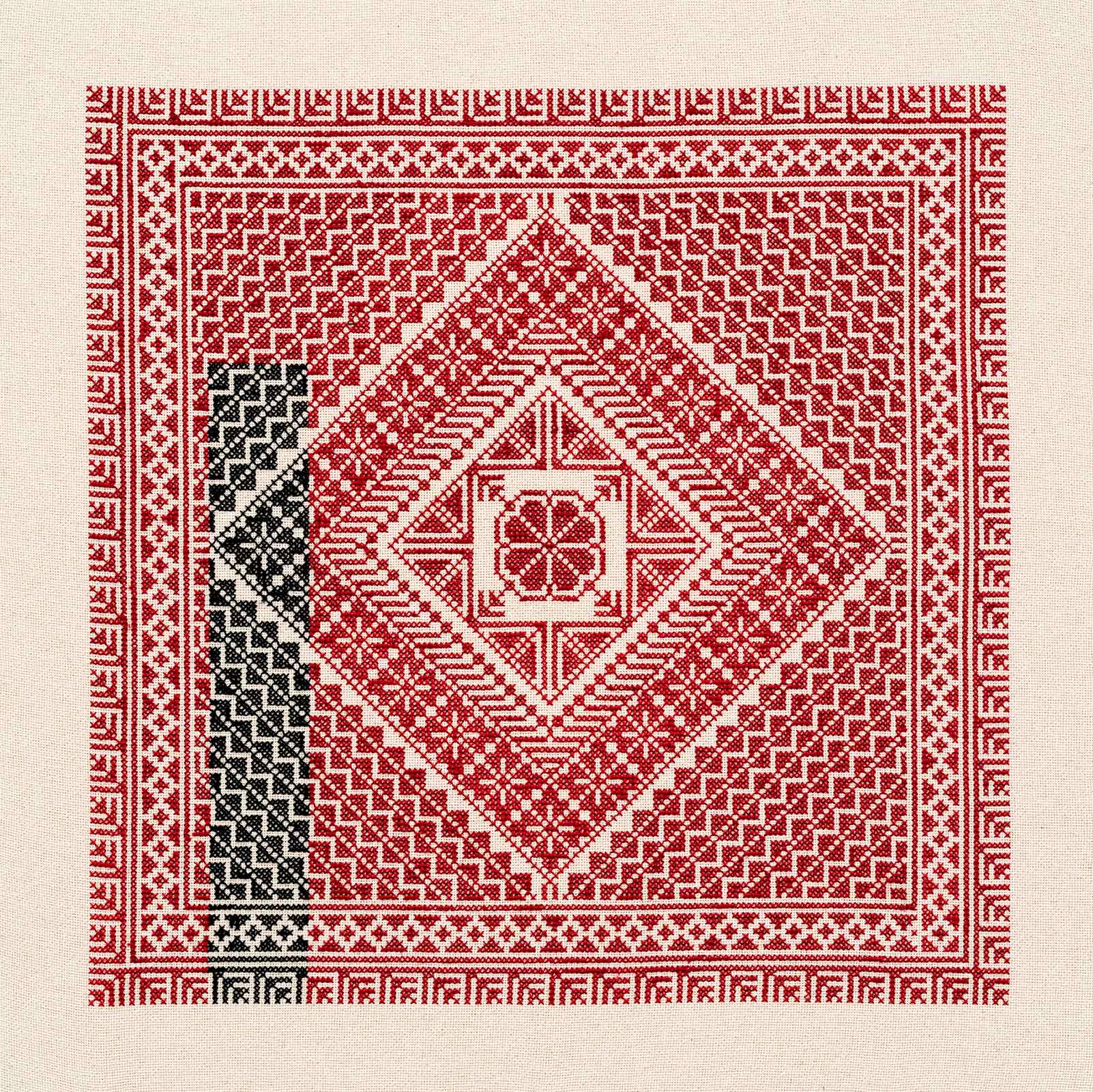

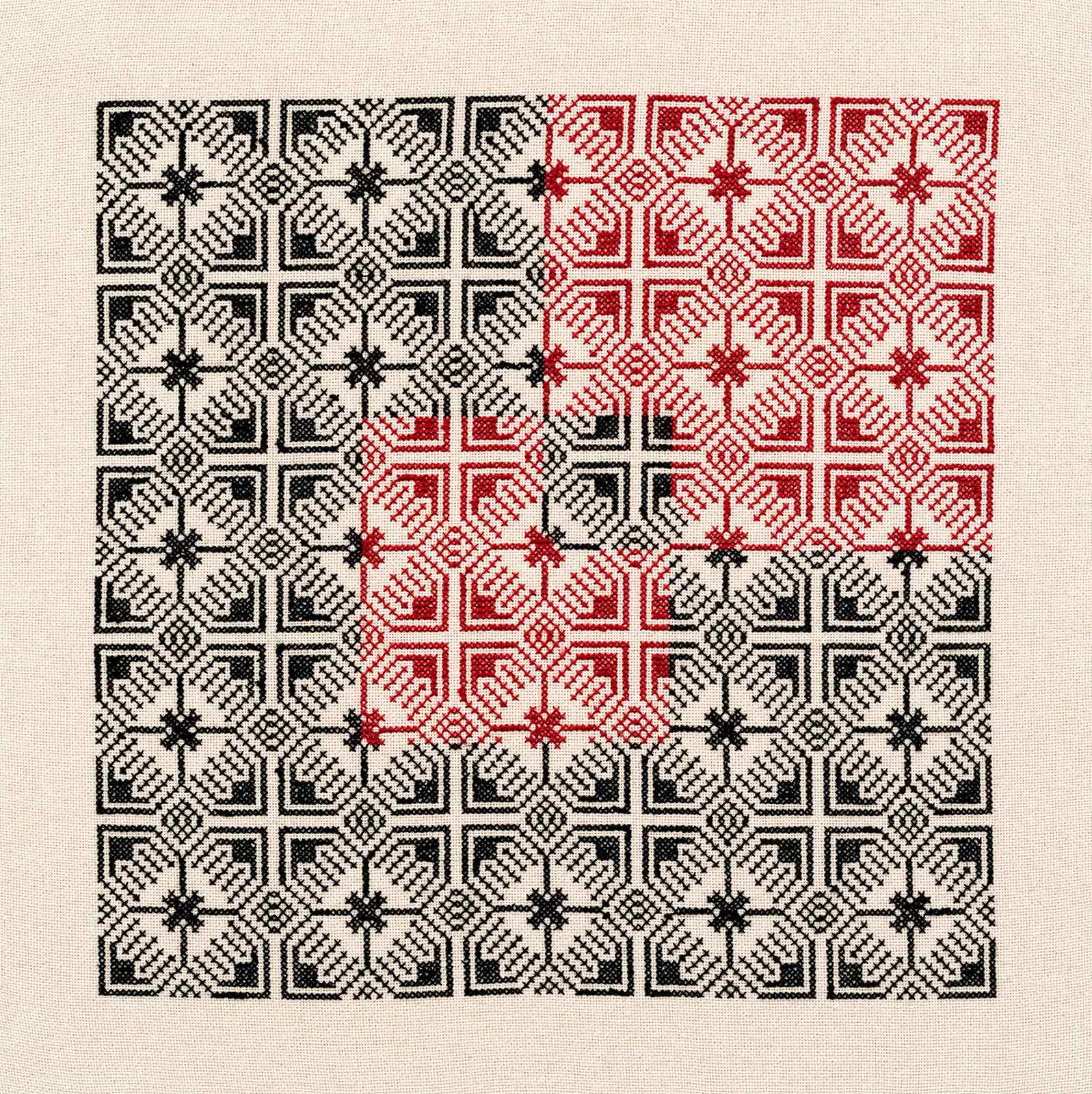

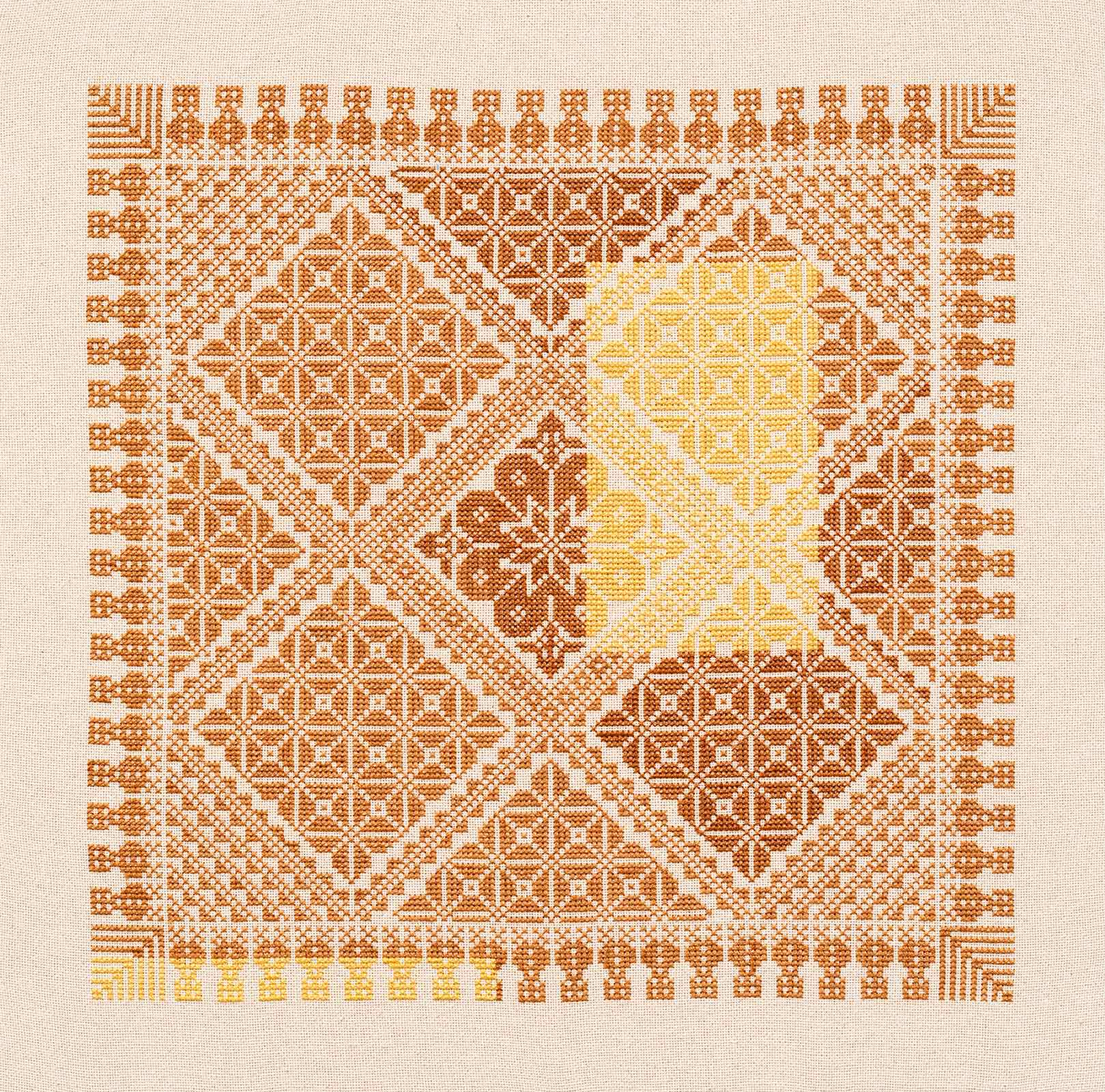

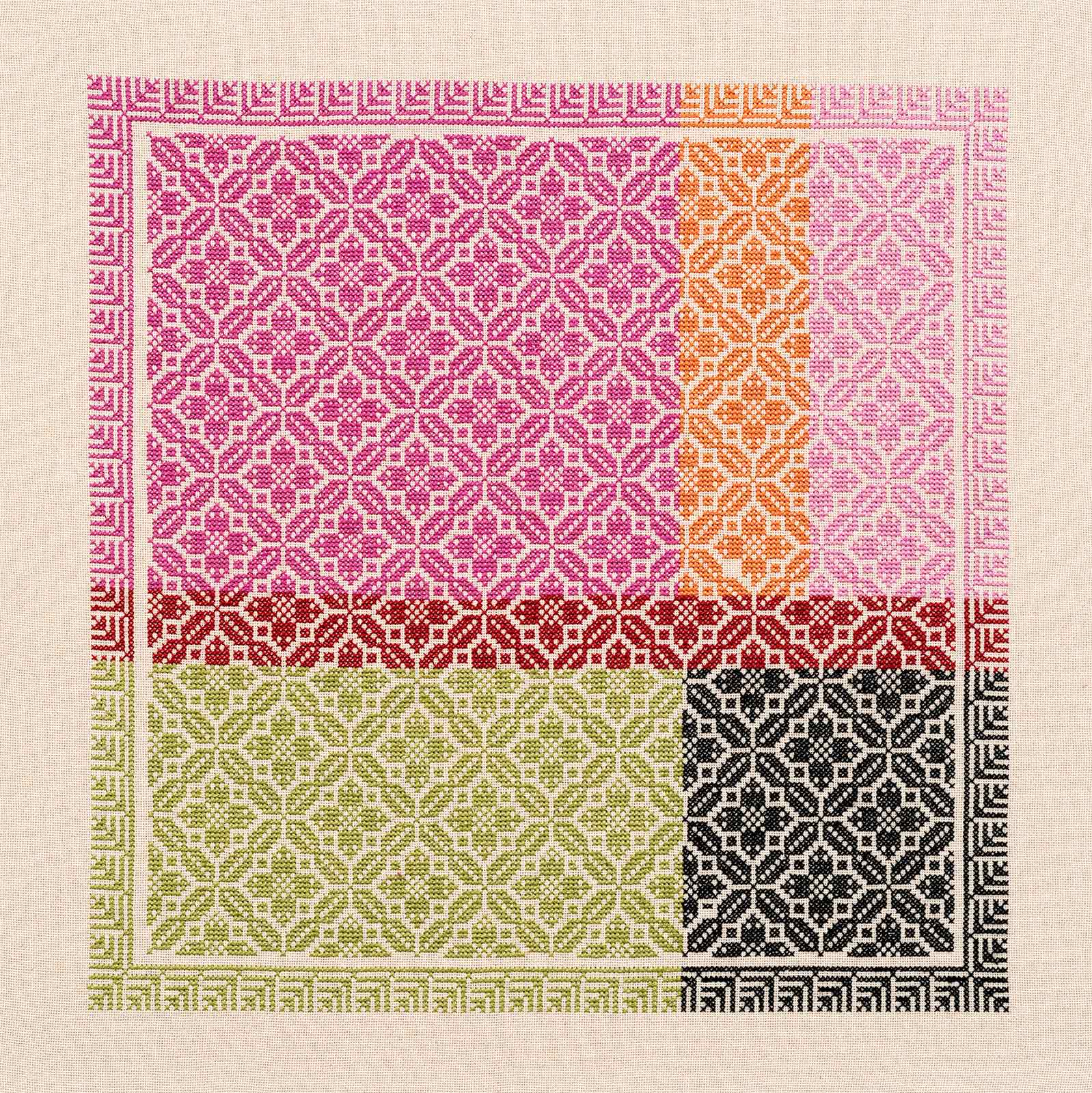

Jordan Nassar—While I certainly have formal concerns, the symbols and patterns in the work naturally have meaning and history. It stems from traditional Palestinian embroidery and relies on the systems of patterning and color that are already established in that medium. So, in a way, I think the work reads as more abstract to viewers that aren’t familiar with Palestinian embroidery. Yet, I’m speaking in a language that already exists. Palestinian embroidery symbols are abstract-representational, I think, but are legible to those who “speak the language,” and includes elements that Palestinians will recognize and register. Every city, village or region have their own symbols, and one’s embroidery communicates that heritage.

Document—You have done a lot of research into Palestinian embroidery patterns, from reading books to visiting craftspeople in Palestine. How has this research come to inform your work?

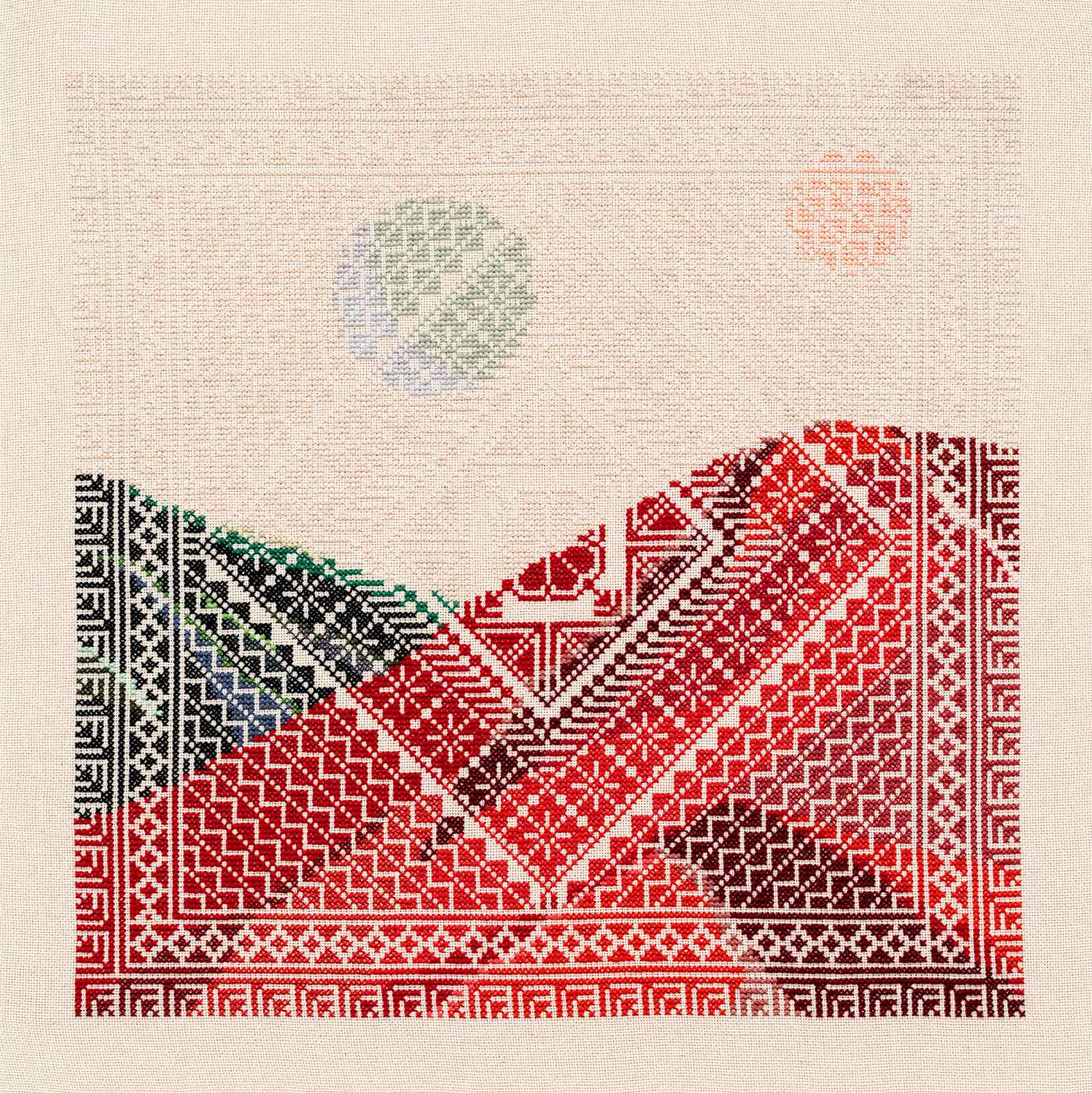

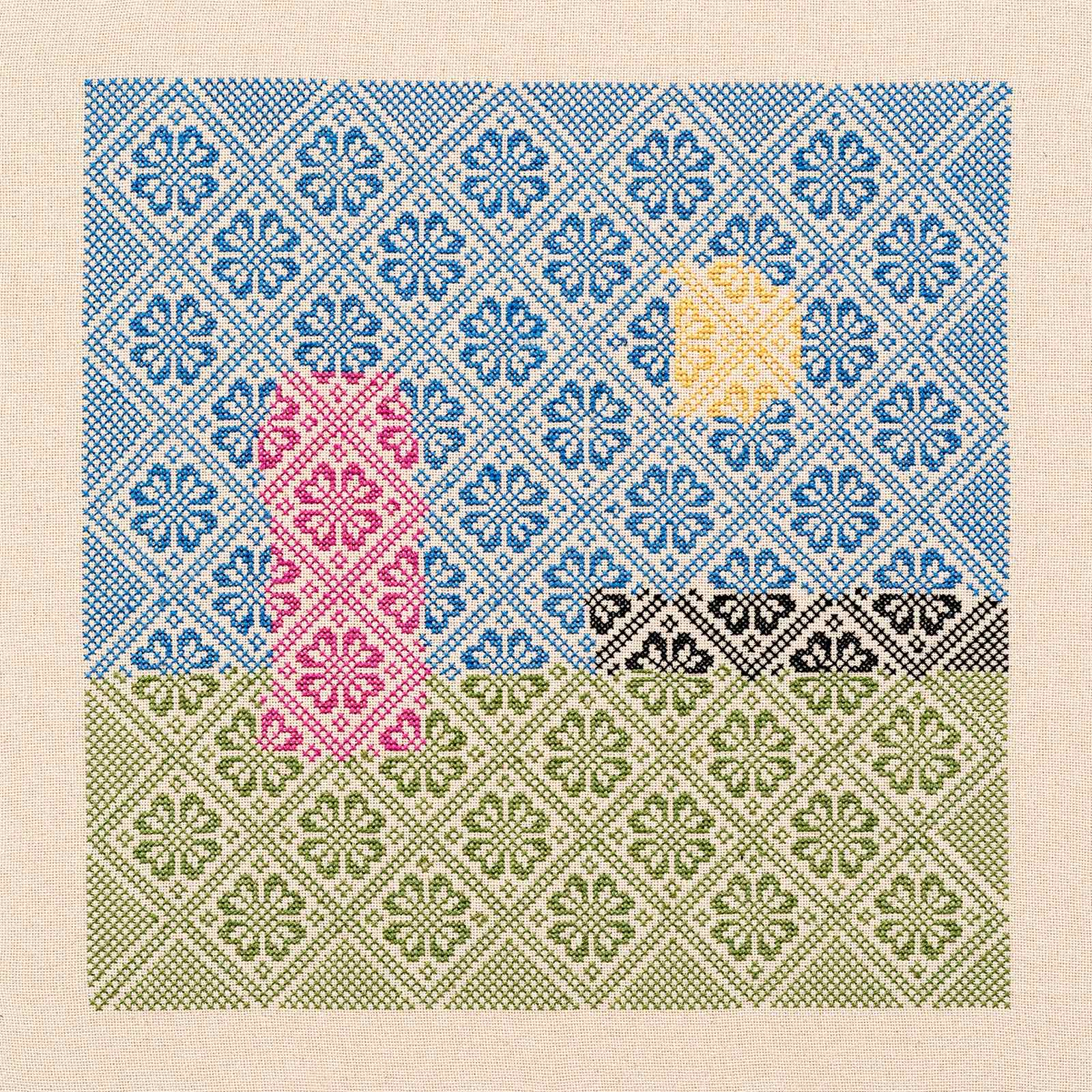

Jordan—Embroidery is something I grew up surrounded with—something I think the majority of Palestinians share both in Palestine and across the diaspora. I didn’t have the traditional experience of being taught by my elders. But, I think the rhythms, the tendencies of the composition, and patterning are something I had a feel for—like being exposed to a second language growing up but not being a native speaker. In 2017, I participated in a residency at Artport Tel Aviv, in Jaffa, from which I was able to go to Palestine to meet with various women at refugee camp centers and small embroidery businesses, and those experiences really had quite an impact on my practice. Working with them, working while in Palestine and Israel, and working so closely with very traditional patterning really advanced my feel for the patterning and structures. My presentation at Frieze is also a direct result of the experience there during the residency, going back and forth between Palestine and Israel, straddling both sides, and navigating that as a gay American, but also as a member of the Palestinian diaspora seeking to make sense of those almost incongruous things.

Document—Your work seems to have started out by presenting patterns in a more straightforward manner, not unlike the fabrics you were referencing. But over time they have grown increasingly complex, often evoking landscapes. What made you develop the work in that direction?

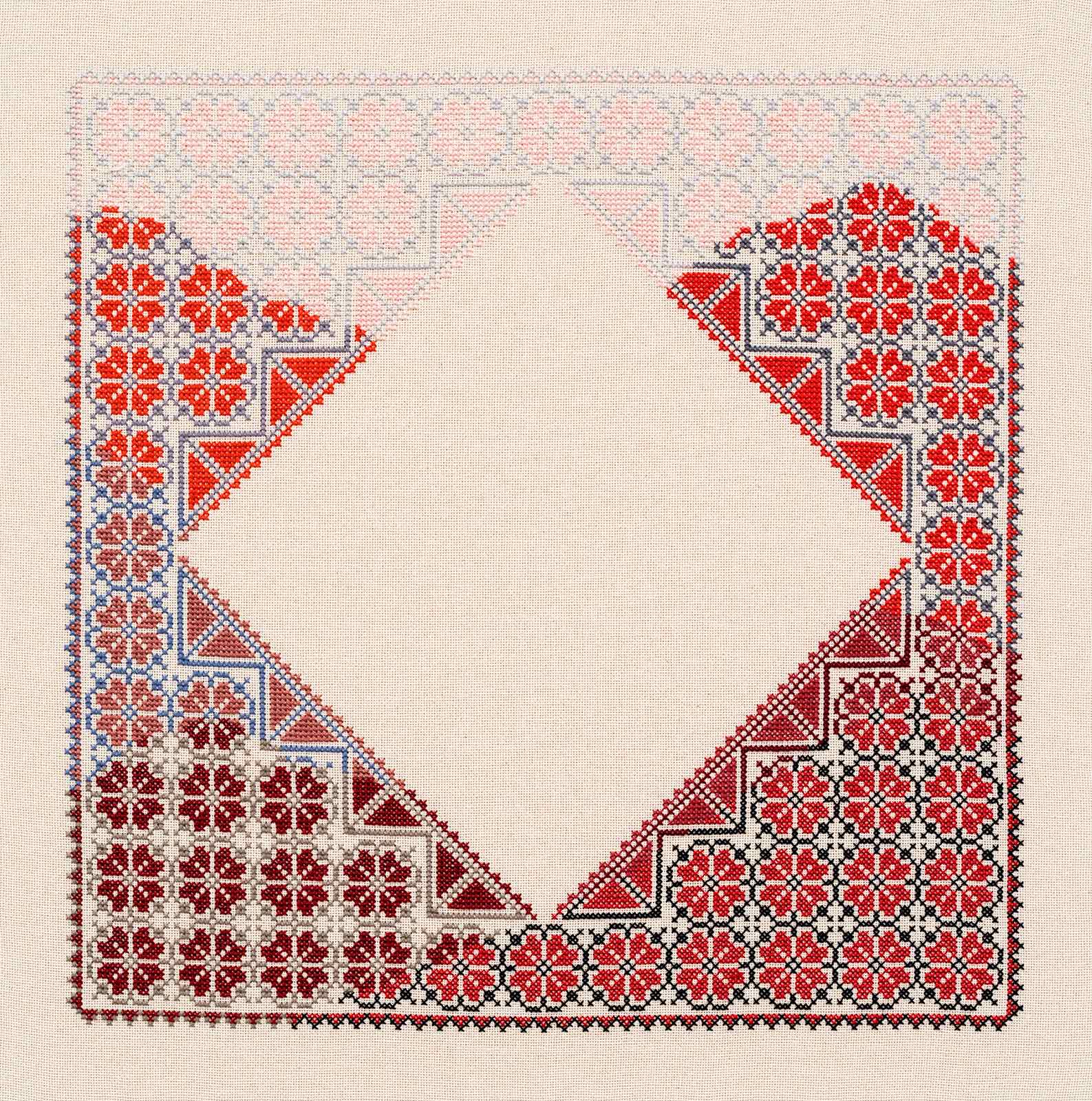

Jordan—As I delved further into the medium and realized that in fact the pattern is really just “my paint,” I think the introduction of breaking the grid with colors and forming figurative shapes has been really freeing. I suddenly could feel like a painter, and this feeling of having an image in my head and then trying to translate it is exhilarating every time. It’s almost like waiting for cookies to bake, since the embroidery is all done by hand it takes a long while to execute. Of course that only adds to the excitement, and I think that is important to the process as well, in the way that it gives me time to change my mind as the work progresses and add to (or sometimes subtract from) a piece. I reference landscapes for the simple reason that I feel it gives the viewer a point of entry, a physical way to locate themselves when approaching the work. The work is very much about color, but rather than going completely abstract, I believe that having that neurotic part of one’s brain feel soothed, making it feel as though it knows what it’s looking at when recognizing a mountain or a horizon, allows for easier access to the work. And of course, I wish to perpetuate the idea that these make-believe landscapes are, in some way, a dreamland, a utopia or a Palestine—for some. To me these landscapes are heartbreaking and filled with yearning, while hopeful and beautiful.

Document—Much of the recent writing about your work, and especially interviews with you, focuses on your identity as a gay Palestinian-American. What other issues, political or otherwise, do you seek to address through your work?

Jordan—As a second-generation diaspora Palestinian, much of my work is me navigating feelings of not being “Arab enough,” being alien to that place that I also have been taught to long for, the idea of inherited nostalgia. And then in a way, claiming all of that as a totally valid way to be Palestinian—though maybe just not so common. Being rather flamboyantly gay is part of my own personal make-up and in line with my art making. With that being said, I’m still Palestinian. Broadly, the work deals with race and ethnicity, cultural heritage, cultural ownership and cultural exchange, conflict, facts and truth, nostalgia, and dreams.

Document—What is the role of labor in your work? Certainly, there is a lot of physical work that goes into the making of each piece. The labor you perform is repetitive at some level. Is that something that you would like to activate in the experience of looking at the work, or is it just the inevitable way that your paintings have to be made?

Jordan—Hand-embroidering everything myself is crucial to me because making this work is fundamentally about me participating in a craft that is part of my own Palestinian cultural heritage. It was something I started doing out of a yearning to connect with the part of me that is Palestinian, especially growing up in NYC and feeling so American, and more so later on once I met and married an Israeli. The notion of repetition hasn’t really occupied my thoughts because this is just how Palestinian embroidery looks. It’s tied to geometry, reflection and mirroring of symbols, but also relates to the body. That being said, my presentation at Frieze is an exception—it is a collaborative body of work I made with the women in Palestine, whom I met in Beit Jala while on my residency. We all embroidered for this body of work together. This entire body of work is based off of a set of pillows I bought from them, that they had made in their own local and personal styles before they knew I existed. From that set, I drew all of the pattering and coloring for this body, based off of their initial aesthetic decisions that are totally informed by a tradition that was handed down to them in the old-fashioned way, a living (albeit endangered) cultural practice.

Document—What is the role gender plays in your work especially as it intersects with this particular craft?

Jordan—To be honest, the fact that I’m male and that this is traditionally a female medium is not really something I’ve ever been concerned with. For me, working with the medium is much more about participating in something relating to my Palestinian heritage. However, I will say that pretty much every single embroiderer I met in Palestine, whether in Ramallah, other cities, or in small villages up in the north, was shocked that I was a man practicing it—some surely giggled a little. One of them, though, once she saw my work, said something to the effect of “Well, it’s because your blood is Palestinian! That’s why you can do this so well!” I felt like I had earned their approval.