As the exhibition ‘A Queen Within’ at the New Orleans Museum of Art enters its final week, Document speaks with the show’s curators about the history of dressing powerful women.

Originally conceived as the first fashion exhibition to ever take place at the World Chess Hall of Fame in St. Louis, Missouri, A Queen Within served as an unlikely sartorial celebration of the shapeshifting powers of the chess board’s matriarch. A collaboration between exhibition producer Susan Barrett of Barrett Barrera Projects and curators Sofia Hedman and Serge Martynov of MUSEEA, the exhibition exceeded expectations of introducing chess to a wider audience, unearthing larger questions surrounding representations of female power—how it’s wielded, displayed, restricted, and often misrepresented. Now in its second iteration, this time at the New Orleans Museum of Art, the curatorial team has expanded the exhibition as a form of commentary in line with the growing conversation on women’s rights and gender performance. The exhibition defines female power through seven archetypes: Mother Earth, explorer, enchantress, thespian, magician, sage, and heroine. Serving as the entry point for the show is a selection from Barrett’s personal archive of Alexander McQueen, which happens to be the largest archive of the late designer’s work in the United States. In its final week, the show’s curators spoke with Document about the continued struggles to properly represent diverse female forms and fashion’s ambassadorial responsibilities.

Document—In what way was your choice of archetypes a critique on fashion itself? There are several points throughout the exhibition that seem to unpack the ways that fashion is problematic or how fashion can be quite conservative with gender definitions.

Sofia—I think any sort of critique comes from the objects themselves. I think as it is a contemporary fashion exhibition, rather than focusing on a certain history of dress, a lot of the designers featured are experimenting with new ways of looking at fashion and design.

Serge—I think we also tried to balance out the critique by including objects that represent solutions, as well.

Sofia—Fashion has a lot of problems but it is also presents endless possibilities, such as the exhibition objects working towards a sustainable future or body positivity. The Alexander McQueen objects from Barrett Barrera’s archive that are featured in the exhibition are a great example of a different kind of approach. The designs themselves don’t necessarily foster inclusivity, in terms of the sizing or shape, but they’re experimental in their storytelling. That kind of fashion was considered to be quite experimental 15 years ago.

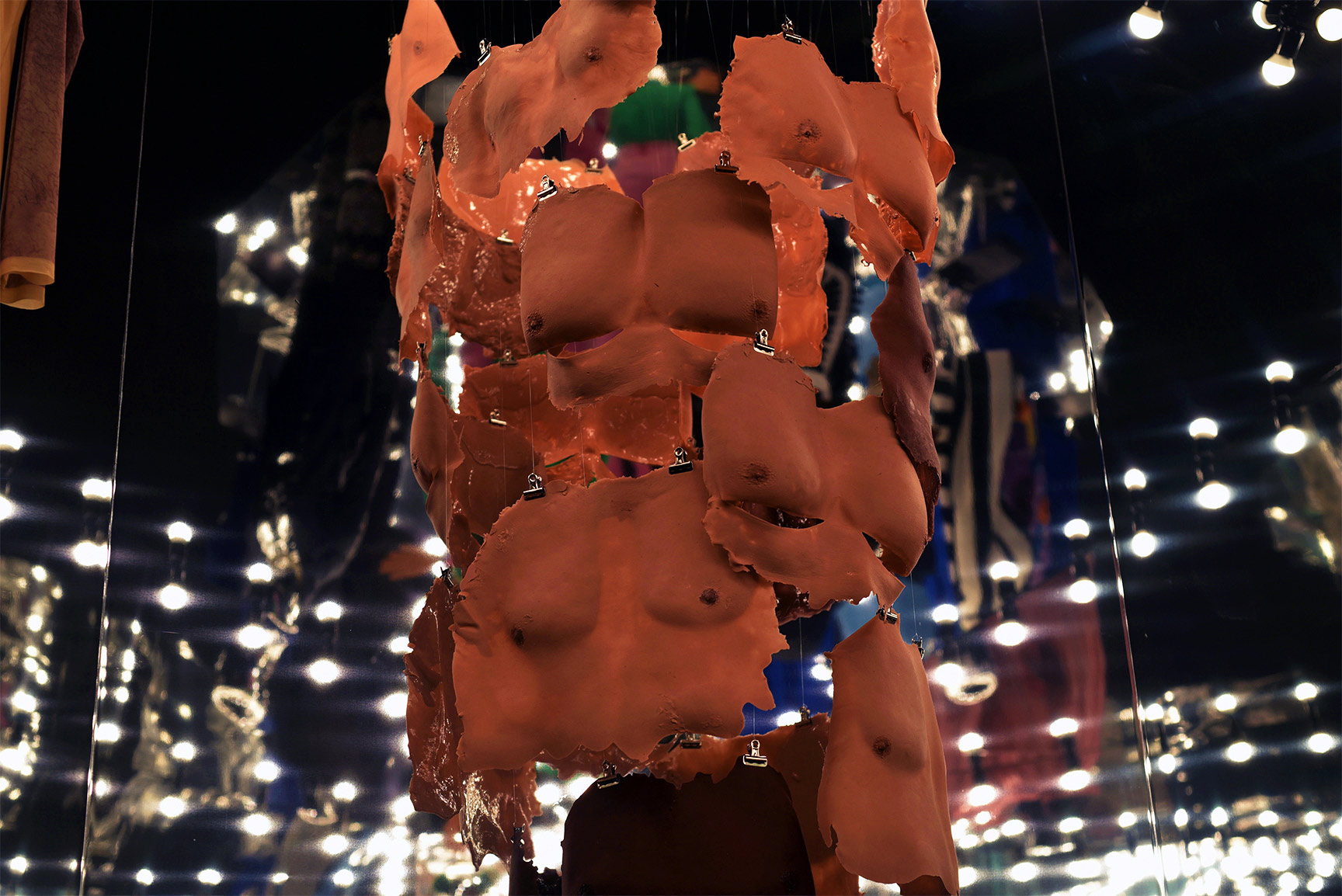

Document—Some of the standout pieces from the exhibition are the Minna Palmqvist dress forms. The unusual shapes are a great example of how these archetypes of female power, and the way that women adorn themselves to communicate their power, often times manipulates or restricts the female body.

Serge—The mannequins are kind of non-confirmative, but rather beautiful at the same time. We wanted to broaden the viewers’ understanding of what fashion is, and what fashion can be. Fashion isn’t just fabric, but it can be other mediums as well, such as forms and actual bodies.

Document—Such as the mannequins used throughout the exhibition itself. I can imagine that there was quite an intense dialogue surrounding your choice of mannequins used for each of the different archetypes featured in order to authentically represent a range of female bodies, sizes, etcetera.

Serge—We really wanted to have different types of mannequins in different sizes and shapes, and we did. But we encountered problems with having larger mannequins because the clothes just didn’t fit. A lot of the garments were made for a size zero, essentially.

Sofia—And even if the garments are a little bit bigger, it might only be a size 8 or something still quite small. If you want to make a fashion exhibition that represents a lot of different bodies, it just doesn’t really…

Serge—The fashion world is still catching up in that sense.

Document—Did you at all consider including how men have adopted these queen archetypes in styles of dress? There’s an argument to be made that drag relies heavily on these archetypes, and could have been an entire entry in the exhibition.

Sofia—We had long discussions with the team, actually, about how to go about it. Ultimately, we felt several of the designers included were addressing these notions of gender performance, and that it is spread across the different archetypes.

Serge—It’s a challenge. Almost every archetype within the exhibition could be expanded upon in a really big way, which is maybe something we may do in the future because we’re very passionate about a lot of these issues.

Sofia—It’s problematic when things get watered down in exhibitions, particularly when it comes to addressing really serious issues dealing with race or gender.

Serge—I think it was also a very multifaceted and complex topic, so we felt that it almost deserved an exhibition of its own.