The Foundling Museum is also set to make a bold institutional statement with the recent launch of a Kickstarter campaign that will fund a new feminist exhibition with one intriguing catch. The show will replace portraits of the museum’s male governors with the 21 women who first petitioned to establish the building in the first place.

The museum, located in the middle of London’s Brunswick square, is leading a charge by major institutions to tell women’s stories. The New York Historical Society, Museum of the City of New York, and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, DC are all collecting protest signs from the recent Women’s March. Choosing to focus instead on more timeless themes of female empowerment rather than political polemic. The broader institutional shift is a needed turn from the habitual erase of women from history to a much needed restoration of their roles.

The politics of what museums house and display dictate a cultural psychology, our conception of national narratives, and are invaluable tools for historical context. But, it’s hard for any collection pieces to tell an inclusive story when curators are among the least diverse cohorts in any industry. According to a 2014 report by the National Center for Arts Research, women run a only one quarter of the largest art museums in the United States—while also being compensated up to 30 percent less than their male peers.

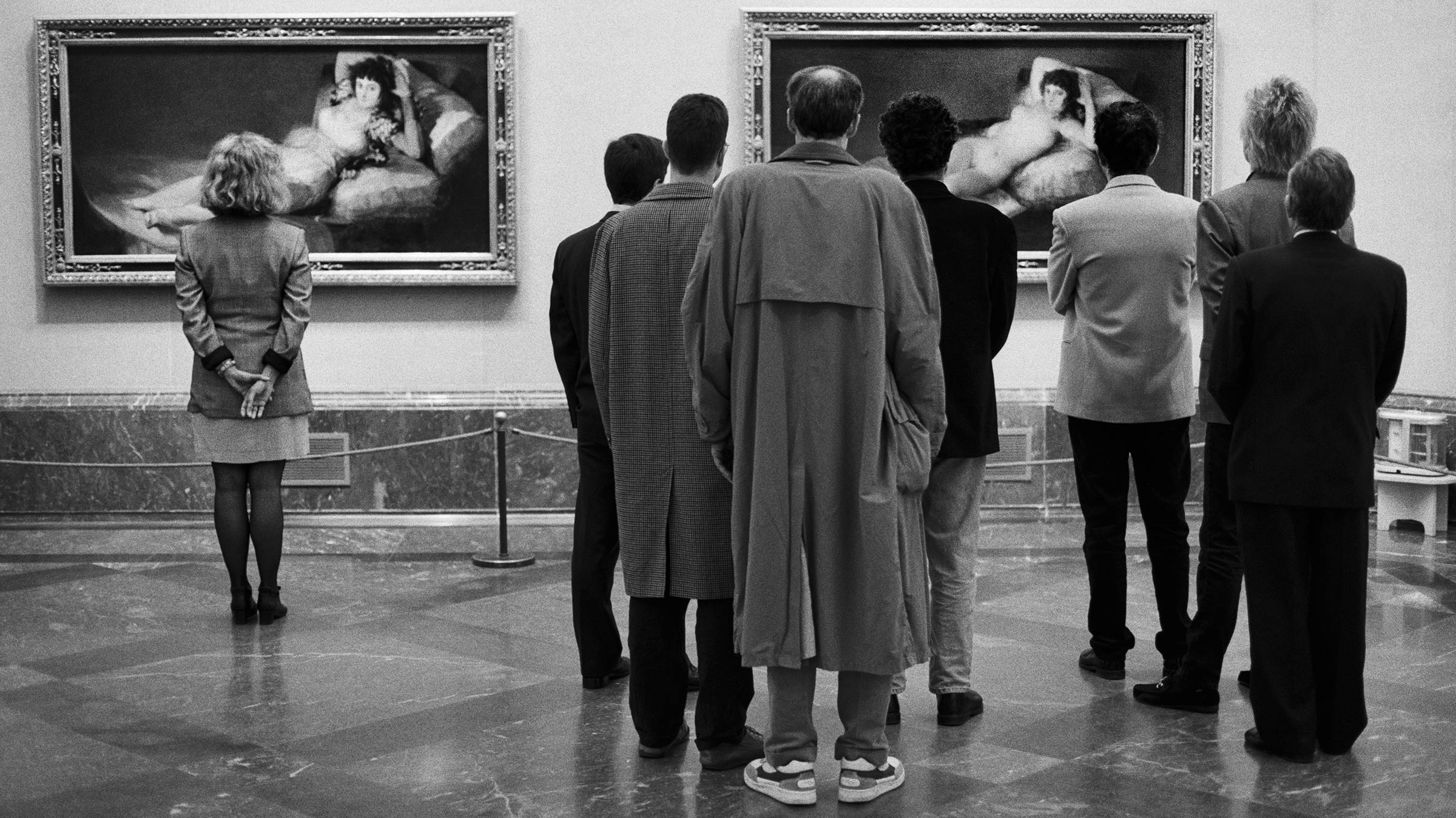

The art world’s longstanding gender balance makes the Foundling Museum’s new initiative all the more timely. The removal of male portrait isn’t erasure, but a balancing act that other institutions have begun to act on. The Manchester Art Gallery has decided to remove one painting, Hylas and the Nymphs by JW Waterhouse—which depicts a clothed man trying to collect water from a pond, surrounded by a swarm of nubile women. The gallery has decided to create a pointed void in the wake of its removal. The space where it was feature will be a bare gallery wall encouraging viewers to leave behind post-it notes with their opinion on the removal. Says Contemporary Curator Clare Gannaway, “Our attention has been elsewhere … we’ve collectively forgotten to look at this space and think about it properly. We want to do something about it now because we have forgotten about it for so long.”