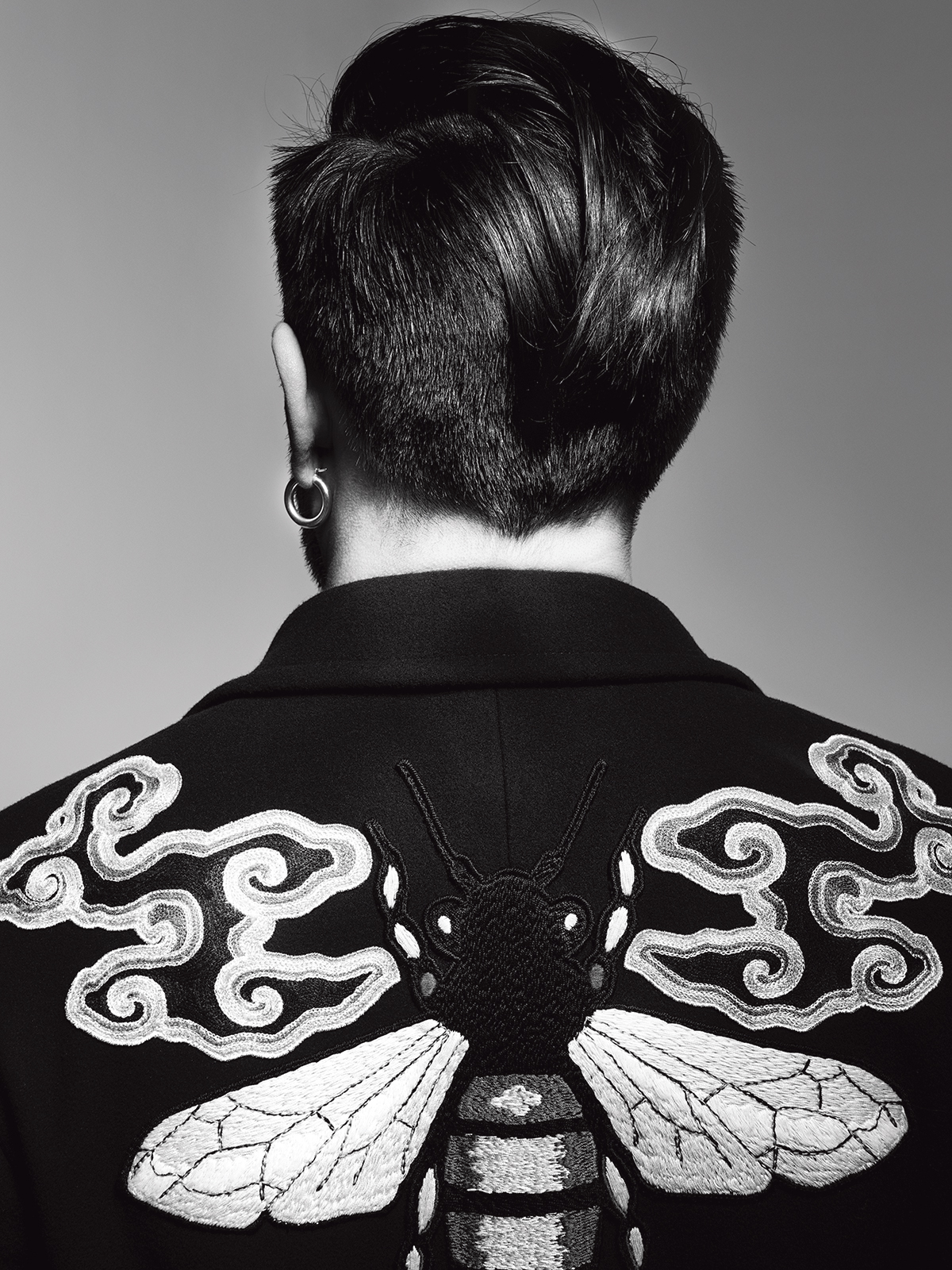

The irreverent British designer visited Knight’s SHOWstudio in Belgravia to discuss artistry, the social paradigms embedded in clothing, and the political ramifications of fashion for Document No. 10.

With Spanish-born Johnny Coca at the helm, Mulberry has revived a more irreverent side of British fashion. Quick to laud the wonders of tartan, the kilt-sporting designer celebrates the punk heritage of London and the importance of music in Britain’s heritage. A brilliant alumnus of Parisian fashion, Coca made the move to London from Céline (where, notably, he cemented the Trapeze bag as a firm favorite in the world of accessories), before showing his first Mulberry collection in February of 2016. Having studied design, his talent lies in fusing fashion with his expertise in furniture and architectural design. First a window dresser at Louis Vuitton, before moving rapidly on to further stints working on design at Tom Ford, Marc Jacobs, and Michael Kors, Coca diligently rose to the top tiers of the industry.

A giant of fashion photography and film, Nick Knight grew up between Paris, Brussels, and London. With his signature multimedia approach to image, Knight humbly nurtures an expansive catalogue of prestigious subjects and collaborators: His archive includes Yohji Yamamoto, Alexander McQueen, Dior, Louis Vuitton, the late David Bowie, and George Michael, among many other contemporary icons. He shaped fashion film at the inception of the format with a digital platform, SHOWstudio, which he launched in 2000, blurring borders between genres, photographic, and filmic techniques in the process. Days ahead of Coca’s third Mulberry showcase at 2017’s London Fashion Week, the pair sat down at Knight’s SHOWstudio in Belgravia to discuss artistry, the social paradigms embedded in clothing, and the political ramifications of the future of fashion.

Patrick Clark—You both deal with multiple mediums. What, in your respective practices, links art and fashion?

Johnny Coca—When you are a designer, everything is related to creation. As soon as you consent to design, you want to create something that is unique. When I create an object, I’m trying to create something that is personal. If I can relate fashion and art, it’s through the emotional aspect.

Nick Knight—I’m pleased to hear you say that. I think commerce has been too big a factor within fashion for the past 10, 20 years. There’s been too much of a push to sell and a playing down of the artistic side of fashion. My personal belief is that fashion is one of the greatest art forms. It’s a form of self expression: We all get up in the morning and dress. It says something about who we are. Art, I think, is communication, which makes fashion probably one of the most democratic art forms. I don’t think there’s a division; I think the process of selling fractures both and forces a gap.

Johnny—What is bizarre is that an object of design has to be commercial, because you want to duplicate the product. Art is increasingly using the same kind of logic. Making that step to sell was more difficult for an artist; it’s just like couture, there’s only a one off piece. Now art is like the market of duplication. Previously it was a one on one selling basis, between artist and customer.

Nick—I started SHOWstudio because I wanted to work in an environment that felt like a studio. When you go to a lot of art galleries, you feel like you’re going to a bank —cold, unfriendly. I never felt that to be true of the artist that created [the work].

Patrick—How, then, do you protect the craft and the artistry?

Nick—I don’t know if you can or even should protect it. I think as a society we should start to recognize fashion as an art form and put it in a place where people actually treat it with more understanding. In Britain, we suffer a lot from the fact that our press is still largely oblivious to fashion and our government doesn’t want to understand it. I don’t want to get too political too quickly, but as we’re talking about government.

Patrick—Brexit, a critical moment in British fashion.

Nick—It was dreadful and absolutely wrong. Of course, the government has no idea how it’s going to affect fashion. If you make a piece of clothing that needs to be cut in one country, embroidered in another country, dyed in the third country, but you haven’t got free trade within Europe, then how does that happen? It’s going to be dire.

Johnny—Fashion can be measured by the cost of fabric, which comes from outside the U.K. That costs so much, because it’s manufactured abroad. We want to keep the quality behind the craft at Mulberry. Fifty five to 60 percent is produced here in the U.K., but we have to buy the leather in Spain, in Italy, in France. What is important today is to try and keep what is really exclusive and well done, focusing on our core local strengths.

Nick—Some of the young British brands like Craig Green and Phoebe English rely on having a very strong European manufacturer. So for young brands it’s going to be very, very tricky.

Johnny—The infrastructure of the industry is unbalanced. There are no massive shoe factories, for example. There are just a few of them. Take Clarks: They recently took their production outside the U.K. We decided to employ their workers for Mulberry, because all the footwear industry is in Italy.

Nick—Fashion is some $25 billion addition to the British economy every year: it’s a huge industry, of course that’s not being taken into consideration at all. As soon as Brexit happens, our manufacturing base is going to collapse.

Patrick—One of the main questions with Brexit, culturally speaking, was how to actually pin down the British identity that was being defined differently by either side of the debate.

Nick—Luckily, I have never had to: I have never been a nationalist. My father was with NATO, so I grew up on the continent. I came back to Britain in the 1970s, and I was really shocked how regimented Britain was culturally. I always felt a dislike for that sort of nationalism, for that [sense of] boundary creating.

Johnny—Growing up in Spain, I was already fascinated by the cultural identity of Britain, especially the irreverence of the U.K. and its playful side. Britain is fascinating because it is multicultural. It is what made fashion interesting for me: There were no limits. I know so many people who come here for research because of that energy. There is this opposition between a classic character and a constant rebellion.

Nick—It comes from the fact that we had a very conservative society throughout Britain; it comes from a very strictly coded sense of dress.

Johnny—What with a monarchy too, historically you have a very strong social structure.

Nick—Exactly! My father would never wear jeans. He would never wear trainers. His view was that it is not right for a gentleman to engage in fashion. In his way, he was the strictest with his dress code. Britain was, and still is, a highly coded society. And that is what, to some degree, gave us youth countercultures. But they too were all very socially coded. The whole skinhead thing that I was involved in for years was so coded. The more pressure you put, the more people rebel. The only thing that will come from Brexit and Trump, I think, will be that rebellion. There is definitely the sentiment of there being a revolution about to happen.

Patrick—Mulberry is anchored in British culture. What were the pressures of working with this identity?

Johnny—It’s totally part of culture here. When you finish university, the first present from your mother is a Mulberry bag. It is a very personal house and very craft based. We’re like a family; manufacturing wise, there are seven families, actually, all working together in the factories in Somerset. When I arrived, I said: “Let’s be careful, there are all these classic customers still there, but I need to bring a very strong creation and creativity in product to drive the brand in a more international way.” I needed to make it more trendy, desirable.

Nick—What you’re doing is establishing a visual language based on the house of Mulberry, and that culture, and making that language a more international language, without totally modernizing it.

Johnny—Exactly. It stems from a desire to revive this product.

“What is bizarre is that an object of design has to be commercial, because you want to duplicate the product. Art is increasingly using the same kind of logic. Making that step to sell was more difficult for an artist; it’s just like couture, there’s only a one off piece.”

Patrick—Nick, you’re often brought in to collaborate on images of artists—either in film or photography—how far can you go in the revolution spectrum? How do you strike that balance between old and new?

Nick—I think you have to see who you’re working for, whether it’s a brand or [Lady] Gaga, Kanye West, or Björk. What I’ve always said to the people I’ve worked with is that you need to build a visual language that is unique to you: You have to develop that and make that the way that people understand you.

Patrick—Speaking of the emphasis of image, do you think that product is overshadowed by campaigns?

Johnny—I love photography. I love everything related to communication. I think it’s really important to have a really straight point of view or image because that produces the desire.

Nick—It’s heartening to hear you say it.

Johnny—I think in advertising, and in pictures, it’s important to create the emotion. The impact of the emotion you create through the pictures is the initial contact between the product and the customer. It’s the feeling of something really personal.

Nick—It isn’t describing a purely mechanical thing: You’re creating an expression, an emotional desire in a photograph. It’s a predictive emotional desire. I remember when I used to work with Yohji Yamamoto—he never used to say, “Show me my clothes.” He used to say, “Show me my dreams.”

Johnny—When you think of image and communication, you’re referencing the dream behind it. You have that freedom in image.

Patrick—Where do you think the fashion industry is heading, taking into account its increasing speed?

Johnny—We have to produce a lot to guarantee results. But if you want to protect your brand, you need to be more conservative and more respectful of what you do. If you want quality, you can’t expect to design a lot of quality things and you can’t expect longevity.

Nick—Tragically, I’ve seen people who I’ve worked with suffering—Lee McQueen took his life, John Galliano was incredibly damaged by his relationship with it. An artist is someone who is super sensitive to the world around him or her. In all its good and all its bad. You pressure people to produce more and more collections. At some point you have to think—actually, this is a fragile person that I’m working with. And I’m working with them specifically because they are sensitive.

“An artist is someone who is super sensitive to the world around him or her. In all its good and all its bad. You pressure people to produce more and more collections. At some point you have to think—actually, this is a fragile person that I’m working with.”

Patrick—Do you think fashion is oblivious to mental health?

Nick—A lot of the companies are businesses, of course, and they apply business rules to how they market fashion. If you’re marketing fashion, it requires you to have an acute understanding of the human condition. And it means it requires more of an understanding of what it means to be an artist. Those are nebulous terms: difficult to understand and to describe.

Johnny—I think the way fashion works nowadays is that you’re not designing for a group: You have to design for everybody. I worked under Phoebe [Philo] for seven years. She said: “I’m not designing for everybody—I’m designing for a very specific type of person. Someone in line with my culture, my emotion and my aesthetic.” The success of Phoebe can be laid down to the respect she had for what she held in her head and heart.

Patrick—What of fashion’s obsession with perfection?

Johnny—When you’re striving for perfection, as soon as it’s done, you want to make something better. While all the components in your head come into being, it’s the mistake on the product that makes it special, unique. That’s perfection: the personal. Take [Pierre] Soulages, all his life he focused on black. When I met him in Paris, he was working in my building. He was never happy about the treatment of the painting he was doing. It was black, of course—but it was never quite the effect or the shadow of black that he was looking for. It was his very own never achieved pursuit of perfection.

Nick—I’m a huge fan of his work.

Patrick—He’s just renounced black pigment. He announced last year he was stopping using it.

Nick—I suppose he would say he was no longer interested how light reflected from black—so the full color spectrum, rather than just black, which of course is a non color. So what is he painting now, I wonder?

Patrick—He’s just started working with red instead.

Nick—[Laughing.] I did a funny thing a few weeks ago: I shot everything in negative. It looks completely different on the screen. You work with a completely different set of values.

Johnny—It’s very difficult because you’re only thinking of how it will look.

Nick—But to be honest, I’m never photographing what I see, I’m photographing what I desire. When I’m composing an image, I’m looking for harmony. I think of my work in terms of audio, rather than visual. Perfection sounds like something finite, as if you’re working towards an object. I’ve never seen my work in that way. I see my work as an ongoing conversation. Relationships, conversations—those are the things that I love. I love meeting people, working out how they see the world. That’s how I see my work, rather than making trophies. I don’t look really for perfection in that way. Society tells us constantly: You should be happy! But I don’t see my work as a way of progressing to a plateau of happiness; I think that’s insanity. Life is infinitely richer because of its problems. There’s an awful lot of value in melancholy.