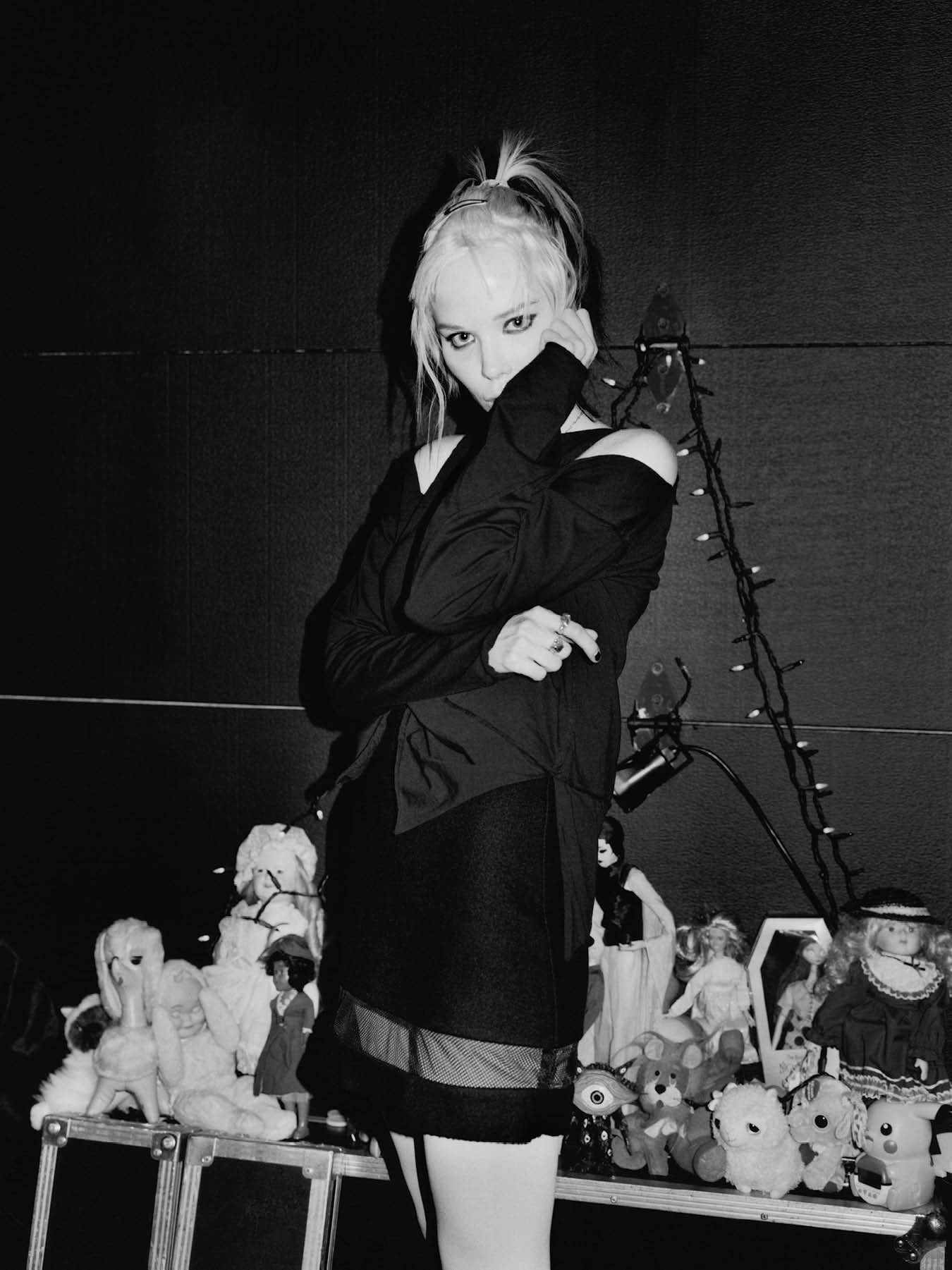

Alice Glass ran away from home for the first time when she was 14 years old. She moved into a dilapidated house in downtown Toronto, split the rent with 20 other teenagers, and, one year later, ran into Ethan Kath high out of her mind in the streets. The two went on to form Crystal Castles, the witchy, bleakly aggressive electronic Toronto outfit that came to define a certain sound of the mid-aughts. The band’s front woman, she was so much more than just a figurehead—she was a magnetic force to be reckoned with. Crystal Castles toured for six years straight, and in October of 2014, she broke out on her own. Now Glass is preparing to release her debut solo album. The new offering is dark—she has compared its sound to “kittens eating their hoarding owners after they die”—and its first single, “Stillbirth,” is an anthem for domestic violence survivors, a screaming, visceral cry. This music is personal—her most intimate offering yet—representing a move toward a style that reaches outside electronica. Lydia Lunch, the legendary No Wave poet, writer, speaker, and musician, called Glass from her home in Park Slope. The two spoke about crawling out of bedroom windows, how the nuclear family is the ultimate fascist society, and just how art has saved them, time and again.

Above The Fold

George Michael’s Epochal Supermodel Lip Sync

Tom Burr Cultivates Space at Marcel Breuer’s Pirelli Tire Building

Brilliant Light: Backstage London Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

LVMH’s Final Eight

Alice Glass: Thanks so much for agreeing to talk with me, Lydia! This is an honor.

Lydia Lunch: I wish I was out in LA driving around with you through Echo Park right now, but we’ll have to do this on the psychic and verbal plane for now.

Alice: I’d like to imagine that. I can’t drive, so I’m going to imagine you driving.

Lydia: I was reading up on you, and it seems that we’ve had a quite similar background as teenage runaways and upstarts. We knew what we had to do.

Alice: I moved [away] from home when I was about 15. I just couldn’t live there anymore and the community I was in, it just seemed like the natural thing to do.

Lydia: Yeah, the microcosm of a fascist society: the nuclear family. Get the fuck out! I ran away for the first time when I was about 13. I snuck out my basement window. I came to New York and I went, “Oh my God, I know what I might possibly have to do and I’m going to go find some money so I don’t have to be forced into that.” So, I went back and got money. I lied about my age and got a job as a maid in a hotel, which was quite convenient if you like to steal and fuck the engineers, which I did. You have to do what you have to do, which is not only escape but create.

Alice: I remember sneaking out a window as well, but we lived in a Victorian house so my room was on the third floor. It was really difficult; I had hoses connected to all the nooks and crevices. It’s pretty fucking dangerous to think about now, but I felt pretty good about it then.

Lydia: I just went back to my hometown for the first time in 30 years and toured a lot of my old stomping grounds. I grew up in a Black ghetto in Rochester, New York, and I kind of traced some of the paths of memorable, horrific moments. I had my first storytelling experiences under someone’s shotgun to my head—paid storytelling at 13. I think that set me on my path.

Alice: It’s weird, the only time that I can really get nostalgic is seeing the alley that my friends and I used to hang out in. It’s always used in movie sets, because it’s cheaper to film in Canada, but they to try and make it look like New York. They always use the exact same alley.

Lydia: When did you start writing, Alice?

Alice: I always kept journals and wrote little bits of poetry. When I was a kid, my parents worked in the city and I was left to my own devices a lot, so I’d just wander around singing melodies. I was in the school choir—I went to Catholic school.

Lydia: Me too! Look at how much good that did us. The devil goes to Catholic school.

Alice: [Laughing.] Yeah, my grandparents were definitely really religious, and my grandmother gave me a lot of Catholic guilt, even when I was going to church.

Lydia: I’ve never had a moment of guilt in my life. My father was a door-to-door Bible salesman at one point and, trust me, he was not at all religious. He was just trying to get into women’s houses. At nine, I was reading this really beautiful, highly illustrated, full-color 10-pound bible, and that’s when I just said, “God is a Marvel comic.” I didn’t have the God-haul that some people have.

Alice: Yeah. When I was 9 years old I had a lot of friends that were boys, and I’d make up stories for us to play that involved being Power Rangers or whatever. One of the most prominent Catholic school stay-at-home moms started a rumor that I was actually friends with them because I was giving them hand jobs. I had no idea what that was!

Lydia: You know, I don’t have a lot of the normal, what I consider “cancer-causing” emotions, and I think it’s because, unlike a lot of traumatized people, I never turned the knife inward. I turned it outward. I started writing really violent poetry and I never felt any guilt. There were a lot of emotions, because I came out of such hatred and anger. But I flatlined and built emotion. The stuff I do is very heavy and aggressive, and people think it’s negative, but I have so much empathy. I’m angry at the fucking world, but I’m not angry with anybody specifically.

Alice: I definitely can relate to that sentiment. I think that trying to channel that energy through art and performance and turning that anger into something creative and positive saved my life. I was someone that did internalize the events that happened to me, and I had a really hard time overcoming depression and feelings of worthlessness. I self-harmed from a really young age thinking it was something that I needed to do. [Music] felt like a relief, like I finally had control over myself. That’s something that I’ve been able to get now creatively.

Lydia: Because all of those emotions are things that people put upon you, they’re not how you ever were. I realized at a pretty early age that whatever the individual circumstances of our traumas were, I should never feel that my experience is unique. I felt that they were universal traumas for women, children, and the nuclear family—I had to come out and tell them. I’m trying to speak for and about those that have a mouth but don’t know how to scream yet or can’t find the words. That’s why so many sensitive, weird, outside “freaks”—and I say that with the highest of compliments—come to both of us. They need the mouth that can scream, that can whisper, that can sing, that can detail and find a way to express the existential horror of existence. Fuck you if you think I’m going to hate shit just because you made me hate you. Oh no, I’m very rebellious. It’s the individual duty as a rebel who will not be forced into the cycle of abuse to find, like what you do in music, beauty through the horror.

“Surviving and existing a lot of the time is like a ‘fuck you’ to all the energy that’s put into trying to destroy us.”

Alice: Yes, wow. I mean that’s my goal. Music is cathartic and I do feel like it’s something that I’m still kind of dealing with. I’ve only been able to get out and realize it now, because I was taking so many things internally and putting the guilt and blame on myself. There are things I’m doing on this new record that I would never have felt confident enough to do before. It’s very emotional music. There’s a personal message behind every song, but what I’m singing about is more than just personal. These past couple years have just been about recognizing that—I think that most people are fundamentally good—but that there are just people out there that take advantage of the optimism that others have for life.

Lydia: Well, there’s also a magnetism to victimology. I guess that’s why I became a predator at a very early age. I used sex as—I wouldn’t necessarily say a weapon—but kind of as a battery charger, and I was always the predator, because I needed an accelerated state of existence.

Alice: I love that. I do think I can relate to that. I think that finding other women in the punk scene that share that kind of sentiment is important, and I really don’t think that you can be punk without being a feminist and without being empathetic towards all walks of life. It’s kind of a little bit like being a hippie but being more aggressive instead of being passive. All of my female friends felt the same way—banding together is kind of what propelled me to not give in and get had, at least not immediately.

Lydia: I came up in a very different time. The late ’70s. The scene that you came out of had a much more—or tried to have a much more—positive community spirit. There was a huge community of various types of artists, musicians, photographers, filmmakers, etc., but we were highly negative in the sense that we were completely disappointed by the failure of the ’60s. Some of the biggest influences on my reactionary behavior were the failure of the Summer of Love bookended by the summer of hate by Charles Manson—very impressive—the Vietnam War, Kennedy’s assassination, and Kent State. These were things that really defined that attitude of my generation to come out and make music that was so incredibly violent. As opposed to, I’m not going to say punk rock, because I’m No Wave—No Wave, to me, means not audience friendly. I always felt outside of every collective I was in. Although I’ve collaborated with a lot of people, I’ve always felt kind of outside it.

Alice: I definitely romanticize the scene you came up in, the late ’70s and early ’80s, because it did feel more individual-based. By my time, it’s kind of like you have a sincere idea of something that can be razor sharp, and then after a while it trickles down and it turns into something that doesn’t even resemble the original. The climate that I was in was completely male-driven, almost like sports or something, where all the local men could sort of come together in the community. I wasn’t so much part of a scene as I was around one.

Lydia: Exactly. That’s what was so interesting about No Wave: there were so many women in bands, doing films, doing photography, doing art, and it wasn’t so much of an issue at that point. It wasn’t a gender issue. We were in a city that was bankrupt, that looked like Beirut on the Hudson, which was so criminal in all aspects, from the government, to the police, to the purposeful burnout of the Lower East Side and the Bronx. Gender was the least of our issues and it wasn’t such a big deal at that point.

Alice: It seemed like, growing up, that women’s liberation wasn’t so much of an issue. It wasn’t something that was really talked about, it was just kind of assumed, but to a dangerous degree where I was idealistic about people that I was surrounding myself with. Me and my friends were all 14 or 15 going to shows, and it was kind of a way for men in their 40s to prey on that idealism. There is one band that’s been [playing] since the ’80s, and in Toronto you had to give respect to them even though they fucking suck. The lead singer guy was in his 40s and would prey on 14-year-old girls—sleep with them in a bathroom at an all-ages punk show. He just kept getting away with it. That was the climate.

“I really don’t think that you can be punk without being a feminist and without being empathetic towards all walks of life.”

Lydia: I was trying to readdress the imbalance of sexual power when I was 13 to probably 24. It felt like it was my duty to go out and be the predator. I felt that I was not just avenging myself, but kind of avenging women in general. I never had any personal animosity against the individual male. My animosity has always been against the greater cabal of the “cock-ocracy” and the kleptocracy and the patriarchy. The problem with society is that it’s not about the rights of the individual, which is what it was supposed to be. It’s not even about the rights of the collective or the majority. It’s about the wants, the greed, the desires of the minority, which is 1 percent of the population. What the fuck is the solution? I don’t have it. But in the meantime, I’m going to continue to fucking complain about it, because all I can do is try and articulate the frustrations and point out that in the last election there was no fucking option. Because they threw the only option under the bus.

Alice: Bernie.

Lydia: Bernie Sanders. The last person I voted for was Larry Flynt because, actually, not only does he believe in freedom and liberty for all, but he actually pays to have political sex scandals in the public eye. Yeah, “Hustler” magazine. Chew on that one for a while.

Alice: It’s great to talk to someone who I feel has a great grasp on the situation, more than anyone else that I’ve really talked to. I went to the Women’s March in Los Angeles, and it was really powerful to see so many people take a stance for humanity and everything, but it’s like, what do we do next?

Lydia: I think every woman needs to know self-defense and needs to be mentally armed if not physically armed. You need to at least feel safe in your own home. When I moved to New Orleans from New York in 1990, 17 cops were arrested. I decided to take gun training because I wasn’t going to be the victim of a fucking road cop. So now I have more gun training than the New York City police force. It’s always been “Apocalypse Now” for me, that’s the state of mind I live in. Numbers mean nothing: one death may be a tragedy, but one million is a fucking statistic—you can’t comprehend it. You can’t comprehend three quarters of a million Iraqis dead. Agent Orange, for what? Because our pawn in the game decided not to fucking play by the rules anymore. Happens over and over again. Welcome to America, asshole. Oh yeah, we’re supposed to be talking about your new album!

“I was trying to readdress the imbalance of sexual power when I was 13 to probably 24. It felt like it was my duty to go out and be the predator.”

Alice: [Laughing.] Whatever. I mean, music is kind of a lot less interesting to talk about right now.

Lydia: Well no, because it’s what saves you. It’s the only way we have to rebel, with music, art, literature, spoken word. Even at my most quote-unquote negative, I still think there is beauty in the “brutarian” poetry. They will not steal my sense of wonder; they will not kill my love of hedonistic pleasure. I always close my solo shows with this: Pleasure is the ultimate rebellion. The first thing they steal from us as women is pleasure at the brink of the apocalypse, pleasure at the mouth of the volcano. Pleasure. And that’s why we create.

Alice: As an individual, I think that just surviving and existing a lot of the time is like a “fuck you” to all the energy that’s put into trying to destroy us.

Lydia: And let’s not only say “Fuck you, and fuck you again,” but, “Hey, you know what? I’m gonna fuck you and I’m gonna like it. There you go motherfucker, how ’bout that?” Can I get an oh yeah, oh yeah?