Creativity thrives in times of upheaval, and many of us now certainly feel the ground shifting under our feet. For the foreseeable future, we’ll be living with and governed by a “whirlwind of negativity,” as the artist Sylvia Maier terms the phenomenon. How will this continuing climate of uncertainty affect the ways we conceive of and produce art and culture in the time to come?

“I am finding words are failing my mouth, leaving me in an increasingly non-verbal state of existence,” wrote the artist Katya Grokhofsky shortly after Donald Trump’s surprise 2016 victory. “Fingers twitching, feet bound, dust settling in my eyes and ears, my languages are not sufficient.” Welcome to the shock event, engineered to jar the political system and civil society, causing disruption among the public and the political class that aids the leader in consolidating his power. We can gain some insight by looking back in time to other moments of crisis and chaos, such as the Crisis of the Third Century or Weimar Germany. While Trump is not a Roman emperor or the führer, the story of how the arts responded to a democracy in peril holds lessons for our day.

Born from Germany’s defeat in World War I, the Weimar Republic (1919-1933) is often thought of as a cultural golden age. It may call to mind images of personal emancipation and creative experimentation. Gay-friendly nightlife; the aural stimulation of twelve-tone music; the visceral impact of Otto Dix and Käthe Kollwitz; the drunken rush of modernity, and its dystopian potential, as immortalized in experimental films like Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis.”

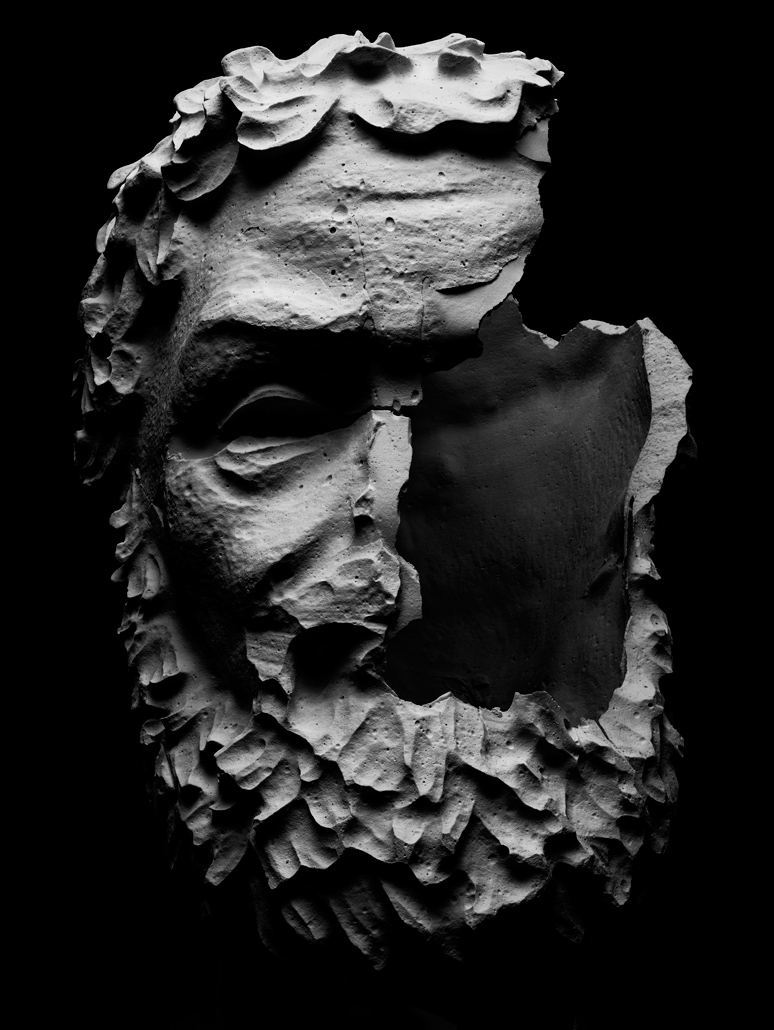

Some of this incredible vitality shows the imprint of trauma. World War I laid bare the inadequacies of visual and other language to render the scale of the horror and its effects on human minds and bodies. “I cannot find words to translate my impressions. Hell cannot be so terrible,” wrote the French lieutenant Alfred Joubaire from the front, unable to draw comparisons with any known reality. The aesthetics of dismemberment, conflict, and shock visible in so much Weimar culture express this search to find a new modern language that contained within it the violence and “ugliness” of the world revealed by the war.

At the same time, Weimar was a place that bred visionaries: men and women who looked resolutely forward and believed a new and better society could rise out of war’s ashes. Architecture became an important site of this big-picture thinking. For Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, the modernist building was a “crystal symbol of a new faith.” But over the Alps, the Italian Fascists, too, created modernist forms as the parallel of political authenticity. “Fascism is a glass house,” reflected the architect Giuseppe Terragni. Only later would fascism’s fans realize that its windows were one-way only, meant to keep them blind while allowing the leader full surveillance of his people. It’s not surprising that artists such as Roberto Rossellini and Federico Fellini, both of whom grew up in this period, adopted Neorealism in rebuke of the interwar’s grand designs, radical experimentalism, and Futuristic sleek forms.

Weimar’s creative burst came, above all, from this extreme instability: the collision of past and future, left and right, poverty and prosperity. Everyday life became uncertain and difficult, as inflation rendered German currency worthless and accusations of a “lying press” took hold. As the historian Peter Gay wrote, Weimar culture was fueled by “anxiety, fear, a rising sense of doom…it was a precarious glory, a dance on the edge of a volcano.”

Hitler rose to power in this climate. He offered Germany the comforts of a return to its “blood and soil” origins, through an extrusion of foreign and subversive elements, along with promises to make Germany great again. With Benito Mussolini as his model, he unleashed violent squads on the populace: Christians as well as leftists and Jews. He found an ally in German conservatives who—ignoring the outcome of the Italian example—thought they could use him to get rid of the left and then cast him aside.

Creativity doesn’t ever stop under such conditions. Certain art worlds might get pushed underground or into tight, hidden places. But you can’t block the impulse.

Once he came to power, he moved with a shocking swiftness to transform Germany into a dictatorship. Within a few years, many iconic works from the Weimar period had been relabeled as “degenerate art,” and the Nazis had transformed their initial “state of emergency” into something permanent, “not the exception but the rule,” as Walter Benjamin wrote in 1940 from his refuge in France.

Many other German intellectuals and artists found their way to Southern Californian towns like Pacific Palisades, which became “Weimar on the Pacific,” a term that hides the difficulties even luminaries like Arnold Schoenberg, Otto Klemperer, and Thomas Mann encountered. I grew up there amidst the many legacies of this collective transatlantic transfer. Schoenberg’s son Laurence (who was my high school math teacher) was the first to encourage my desire to study the impact of political upheaval and repression on the creative process.

And so the long arm of artistic and intellectual reaction to loss and demagogic destruction reaches out from Berlin to our present day, and to a vision on my smartphone screen of a man haranguing crowds at a rally, engaging them in a loyalty oath and chants about locking up his political opponent. I ran home to write an op-ed piece, feeling a sick sense of urgency. Everything that Trump has said and done since then has been deeply familiar to me as a scholar of authoritarian regimes—which is frightening but also offers opportunities to learn from popular resistance to their rule.

Many artists are engaging with what it will mean to practice their craft in a context of greater repression. For every Walter Bernstein—the 97-year-old screenwriter who was blacklisted for 10 years during the McCarthy era and now speaks out today about the dangers of Trump—there are multiple creative people who, after eight years of Barack Obama, have never grappled with the politics of shock and intimidation.

Some remain wary of the “good art comes through struggle” adage. As artist Wolfgang Tillmans reflects, “There is nothing comforting about seeing economic situations decline and nothing edifying about dictatorships rising. I prefer peace, equal opportunities, and prosperity for all to any romanticized artists-fighting-back emergency.”

There’s also the fact that this “new reality” is not that new for many people of color. We need only think of Philando Castile, killed by the police as he reached for his car registration with his girlfriend Diamond Reynolds and young daughter looking on, to remember that the culture of threat we associate with the Trump administration already operated with frightening efficiency. “As a person of color, who is also transgender, our community has always felt the way that people are feeling today with almost every presidential election,” says musician Tona Brown. “I think this election is just forcing a lot of people to confront a dark reality that so many others already face on a daily basis,” adds painter Genevieve Gaignard.

This history of dealing with repression can be a precious guide to us now. We’ve already seen how civil rights leaders such as U.S. Representative John Lewis have been at the forefront of adapting resistance strategies such as sit-ins to our current political situation, but it won’t be easy in the coming times. Along with the prospect of defunding crucial arts and cultural organizations like the National Endowment for the Arts, National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the Trump administration’s moves to criminalize protest and empower the “public safety” sector will likely make public protest more difficult, and with it art that happens in the streets, or that depends on the documentation of acts of civil resistance and freedom of speech. Testimony will be even more vital, and for that reason will probably be made more challenging to collect.

Jazz musician Vijay Iyer worries about the greater pressures placed on artists by the strongman state, but says: “Creativity doesn’t ever stop under such conditions. Certain art worlds might get pushed underground or into tight, hidden places. But you can’t block the impulse. That is a simple fact, as old as humanity.” The role of the artist in this situation is to “offer a different sense of what’s possible, and to inspire others to imagine a different reality for themselves. And, we hope, some might be moved to take action.”

Times of political emergency force us to reexamine all that we have taken for granted: rights connected to our occupation of public space, to free speech, to the legitimacy the state accords us as beings based on our skin color, sexual orientation, and country of origin. As Benjamin intuited during his own flight abroad, crisis can be generative of art because it contains within itself a wide horizon of choices and possibilities. What we must guard against, in the coming times, is that window closing.

The history of resistance to authoritarianism has given us one sure path: the power of being seen and heard together, whether at protests, town halls, or cultural events. “We’ve seen in the past that the arts give people moments of unity, moments of solace and meditation, rituals of emotional catharsis, and opportunities to gather, build, and organize,” says Iyer. When politics aims to tear people apart, art and culture can bring us together, not least by reminding us all of our common capacity to dream and wonder at the beauty and power of the creative process.