When Yvonne Rainer arrived in New York at the age of 22, she immediately sensed the endless possibilities before her. Soon after, she began studying dance under Martha Graham and, later, Merce Cunningham. Despite several critics telling Rainer that her legs were too short and that her torso was too long, Rainer found that dance and choreography were her calling—at the time. As one of the leading figures in the Judson Dance Theater collective, which blended dance with experimental performance art, Rainer pioneered minimalism in dance—departing from the deliberate, emotional motions in modern, and the graceful, poised movements in classical. Rainer gravitated towards experimental film in the 70s, challenging conventional notions of class, gender, and politics, settling into her role as a filmmaker until 2000, when the ballet dancer Mikhail Baryshnikov came calling, and she returned to choreography. Curator, art historian, and Performa founder RoseLee Goldberg commissioned Rainer to create RoS Indexical—which combined not just her dance and films, but also her writing, sketches, and score—for the 2007 edition. Here, the two get nostalgic about the old downtown, discuss the 2016 election, and examine how to remain radical.

Above The Fold

Fashion’s Next, Cottweiler and Gabriela Hearst Take International Woolmark Prize

Designer Turned Artist Jean-Charles de Castelbajac is the Pope of Pop

Escaping Reality: A Tour Through the 57th Venice Biennale with Patrik Ervell

Tomihiro Kono’s Hair Sculpting Process

Yvonne Rainer—Performa is my angel.

RoseLee Goldberg—Indeed, we declared you a national treasure some time ago! We made a commitment in 2007, after working with you, to take care of you and your work in every way. Let’s talk about your extraordinary history, over five decades. What did it mean to be radical in the early 60s; what does it mean today?

Yvonne—What did it mean then? It’s much easier to answer that than what does it mean now. I don’t know what it means now. I can talk about what I and my peers came out of. We were all studying with Merce Cunningham and also taking ballet classes. Yet, to be radical at that point for most of us was to ignore such training and to do entirely different things. I didn’t have classical training, and yet to do Cunningham’s work you needed ballet (although he tried his best to dispel that idea). He felt that ballet is very rigid and played around with it—even so, you needed that technique to do his work. So I was a little bit of a maverick in terms of extreme radicalism. I was absorbing everything I learned and incorporating it into my own work. There was a duet I did with Trisha Brown in which I performed a ballet adagio, and she did bumps and grinds. So for me radicalization or radicality was about juxtaposition. “Radical juxtaposition.” That term comes from Susan Sontag and was key to what I was interested in. These days I think I’m still playing off all that I absorbed in the 60s.

RoseLee—One of the radical ideas of the time was dipensing with music.

Yvonne—John Cage was instrumental in thinking about music and dance being separate. He played piano for Cunningham’s classes and was always around the studio. You know, it was a much smaller art world then; you would run into John and Merce at art openings—everyone knew everybody. Looking at the photos of the audiences now, you see the same people in every one.

RoseLee—It’s hard for people to imagine how small those audiences were. SoHo was quiet day and night, except for factory workers, truckers, and the art community who were living and working there. We owned downtown. Nobody came there.

Yvonne—There was a strictly uptown-downtown split.

RoseLee—What about the relationship between John, Merce, and the group of dancers, musicians, and artists that was active at Judson Memorial Church?

Yvonne—Merce always said the Judson people were “John’s children,” because what was going on at Judson really had very little to do with what Merce was doing. Rather, it had everything to do with Cage’s ideas, such as indeterminacy—chance operations like throwing dice or consulting the I Ching to determine sequence or even movement. Some of the lesser-known Judson regulars were violinist Malcolm Goldstein and his dancer wife Arlene Rothlein, who made group pieces after French paintings; and composer Philip Corner, who had taken the famous New School course in 1955/56 with John and who made a piece in which he played the piano with his feet! There was Fred Herko roller skating on only one skate, and others who converged at the church. The performers who came to be more renowned and who are, with one exception, still active were Steve Paxton, David Gordon, Deborah Hay, Lucinda Childs, and Trisha Brown. Corner made a collage kind of score for me for one of my dances, but I was more inclined to use classical music in relation to what you might call postmodernism. A “running dance” like We Shall Run had people running and separating, and a very bombastic section of Berlioz’s Requiem accompanied it. That juxtaposition interested me.

RoseLee—How conscious were you of the shift to conceptual art of the 70s?

Yvonne—By the early 70s I was moving into experimental film, so I was out of touch. In fact, around that time I went to a Philip Glass concert and fell asleep! I never went back! I kept up with my peers-—Steve Paxton, Trisha Brown, Deborah Hay—but not the broader avant-garde music and dance scene.

RoseLee—At which point did you pick up a camera?

Yvonne—What made me make that transition? A number of factors: aging; illness; I didn’t see movement coming out of this body with the proclivity I once had; the women’s movement, which made me start investigating my position as a woman in the patriarchy. What else? I had followed experimental film from the time I was a teenager in San Francisco: Maya Deren, Brakhage, Cocteau, and later Tati, Chaplin, Keaton. I saw possibility for introducing political subject matter into experimental formats and forms in film which seemed to offer a wider palette than I was able to elaborate in dance.

RoseLee—How did you move to the eye of the filmmaker from the body of the dancer?

Yvonne—All of my films contained characters who were some kind of performer. The first film, Lives of Performers begins with a rehearsal of a dance where you see this group moving around in the studio and hear my voice giving directions. This was around 1971, during this transition period of three years in which I was still making dances and performances.

RoseLee—You weren’t drawn by the film theory of the time, which was highly structuralist, based on semiotics and linguistics?

Yvonne—I was living with a conceptual minimalist artist and reading the same material he was, like Robbe-Grillet’s For a New Novel and Roland Barthes. Later, I would immerse myself in the British “screen” and struggle with the writings of Peter Wollen, Stephen Heath, and Laura Mulvey. It gave me a language to clarify what I was doing. In the scripts I was writing, I was flying by the seat of my pants, with a column of actions here and a column of images there. Playing on a whole history of the use of language in film: subtitle, intertitle, voiceover, synched sound.

RoseLee—How many films did you make?

Yvonne—Seven feature-lengths made between 1972 and 1996.

RoseLee—When was the last time you looked at them?

Yvonne—Oh! [Laughs]. Quite a while ago. 1996 was the last film, MURDER and murder. I loved writing the script and editing the workprint. I just hated production. I always was a techno-dummy, and the social hierarchy at that time making films—even experimental films—was very traditional. The director had the last word with the lowly production assistants scurrying around. I just was very uncomfortable with that…also the writing.

RoseLee—During filmmaking, were you thinking dance?

Yvonne—Yes, always. In fact I used to joke with Trisha: “I still have these ideas about movement, I can send them to you for you to use!” It was always lurking around, and when I came back to dance it was such a relief.

RoseLee—What was that film saying about the body?

Yvonne—MURDER and murder is about lesbian love—I’d come out about 1990—and also about medical attitudes about breast cancer; I’d had a mastectomy. Between 1996 and 2000, I wrote poetry and had a lull.

RoseLee—How did you write poetry?

Yvonne—I had always written and I’d kept a diary.

RoseLee—Was that a decision to go from writing prose, which you do so beautifully, to poems?

Yvonne—I just began to put words together in a different way. The poems are autobiographical. Martha Gever and I were traveling during then, so a number of the poems deal with my observations in Spain and other places. And I haven’t written poems since! Then Mikhail Baryshnikov came along! He invited me to a production of his White Oak group, and days later the phone rang: “This is Mikhail Baryshnikov.” He wanted me to make a dance. I hadn’t done choreography for 25 years! So I raided my icebox from the previous 15 years of choreography and, with the help of Pat Catterson, who studied with me in 1969, came up with a half-hour dance, After Many a Summer Dies the Swan. Misha was in it too.

RoseLee—What was that like to work with someone with perfect classical turnout?

Yvonne—I went to the White Oak Plantation in Florida. Misha’s patron adored him from the time he defected and built him a gorgeous studio. The White Oak dancers including Misha were there—two of whom dance with me today. Misha was great, but doesn’t like to rehearse; he’s impatient, he loves to perform.

RoseLee—That was your first time not being in a piece?

Then Mikhail Baryshnikov came along! He invited me to a production of his White Oak group, and days later the phone rang: “This is Mikhail Baryshnikov.” He wanted me to make a dance. I hadn’t done choreography for 25 years!

Yvonne—I was in all of my dances up through the 60s, even into the last dance, Continuous Project–Altered Daily. Swan was made for his group.

RoseLee—Standing outside looking onto the dancers, you were coming out of poetry and before that out of film. Are you back in a dancer’s brain?

Yvonne—I was picking up where I left off, absolutely.

RoseLee—The language and poetry break, does that shift?

Yvonne—There was language in Swan. I collected last words of famous and not-so-famous people on their deathbeds, like my sister-in-law, who actually said, “See you later alligator.” Various dancers would speak these lines. Then Misha at one point, when someone brings out his glasses, reads one of my poems.

RoseLee—What do you think he was responding to in your work? He comes from extreme training of the Vaganova.

Yvonne—Misha wanted to keep performing! He wanted to keep moving and he saw our work as a way for him to do that.

RoseLee—Did you do additional pieces with him?

Yvonne—Yes, he organized Past Forward, where he invited former Judson choreographers to contribute work. Steve Paxton had taught Misha his solo, Flat. His version was originally 20–25 minutes. Misha doesn’t have much patience for long-duration, so he had done a 12-minute version. I only know this from hearsay, that Misha invited Steve to perform the piece in Paris; Steve did his longer version. The audience went crazy—whistling, hooting, reading the newspaper, leaving the theater—they couldn’t stand it. So talk about radicality—there it was on a plate! Of all audiences, the Parisian audience knows what they like and what dance is not!

RoseLee—There is a long tradition in France of reacting vociferously to a performance!

Yvonne—I heard that when Merce was once in Avignon, at intermission the audience bought fruit and threw it at the performers. When I would be present at a screening of one of my films, I would always stay mainly to see who walked out and when.

RoseLee—Your infamous No Manifesto, written in 1965, still holds so much importance, maybe even more so today, where there is so much “yes” to everything.

Yvonne—Manifestos belong to a particular historical period and are in engagement or confrontation with the rules or paradigms of that period. My particular manifesto—it’s the only one I’ve ever written—was the tail end of an essay about a dance called Parts of Some Sextets in which I wrote, “If the implications of this dance had been brought to some greater extremity, it would have resulted in a kind of manifesto.” I listed all the things that came to be part of this manifesto, which continues to be carted out whenever anyone writes about my work. In 2008, the Serpentine Gallery in London asked me if they could publish it. I said, “Let me reconsider it,” so the form it takes now—and all future iterations—will show it in two columns:

[Yvonne reads the manifesto]. “No to spectacle/Avoid if at all possible.” “No to virtuosity/Acceptable in limited quantities.” Of course all of this is tongue-in-cheek. The funniest thing is: “No to trash imagery.” I was fed up with all this junk aesthetics. “No to the anti-heroic/I don’t agree with that one.” “No to the heroic/Dancers are ipso facto heroic.” “No to style/Style is unavoidable.” “No to camp/A little goes a long way.” That’s my favorite. “No to moving or being moved/Unavoidable.” I’d never meant this manifesto to be prescriptive and never intended to follow it myself.

RoseLee—As you said, it was a conclusion of a work, a summary rather than instructions for a future work

Yvonne—Yes, and saying how it did not fulfill the implications of this same work. I was admitting to failure, in a sense! [Laughs]. But hardly anyone who writes about my work can resist invoking the original manifesto.

RoseLee—Yet in some ways it captures the “essentials” of your dance thinking at the time and the radical position that you presented in your work at Judson. Walking, running, the democratic body. It is useful as an instructional tool, to examine the ways in which you systematically stripped dance to its essential motor elements, while adding a kind of everyday reality.

Yvonne—It was also a way to clear the air.

RoseLee—We’re talking about work from five decades ago and about the experience accumulated over time, of how it is possible to be “forever radical,” to constantly rework the original radical concepts and values. Maturation—in the best sense—allows one to understand all the elements one was using early on, how to use those elements, to play them. You can let go of what you can’t do. I’d be interested hearing your thoughts on time-as-experience-as-expertise in the many fields you work in.

Yvonne—I was very impressionable growing up; and when you’re young, you’re absorbing everything: the world, every idea, reading voraciously. Then comes a point—partly it’s ambition—to make your mark and distinguish yourself. There is an ego trip and competitiveness, and you start looking at things that are taken for granted or time-honored.

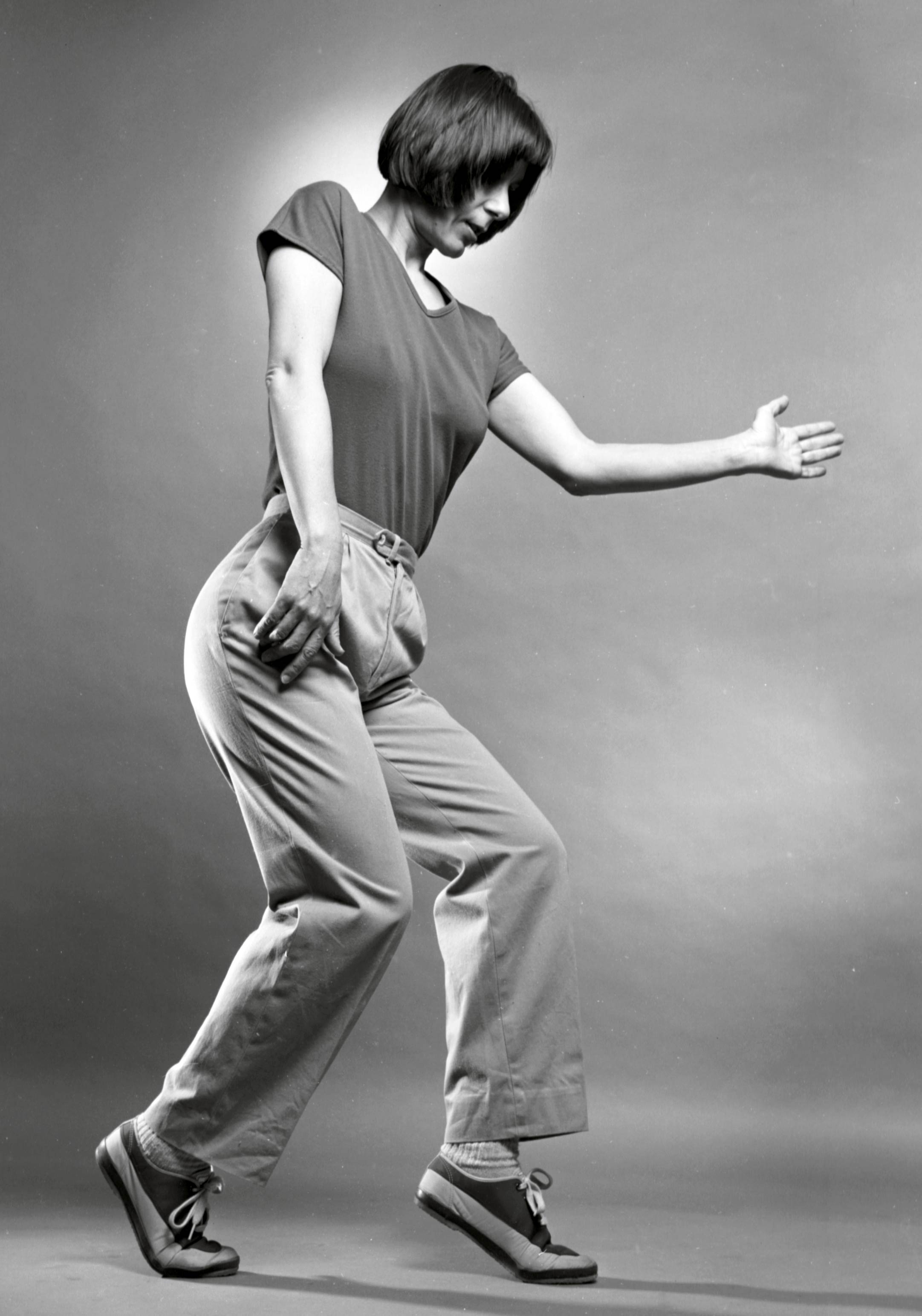

I was never a natural dancer. I’m not limber; my body is short-legged with a long torso, which is not a classical anatomical arrangement. So what do you do to distinguish yourself? You confront your training and history and you make your move. The very first movement of the very first solo, Three Satie Spoons was this: [Yvonne points at her cheeks, twists her fingers, then stretches her mouth open in a monstrous grimace].

RoseLee—Wait, stop. What did that mean?

Yvonne—The forefingers twisting on the cheeks was something a friend did a lot when she was trying to explain something. I don’t know what it meant in her, but it stuck in my mind. My contribution was to add streching the mouth.

RoseLee—Was it in a performance?

Yvonne—Yes, Three Satie Spoons. It’s still in my repertoire. I have very exact notes about the dance. So coming back to dance and the way I operate now, there’s all this baggage I’m carrying around; my work now is full of very early dance moves. I put them together in different ways, and I think about connecting them inappropriately or unpredictably. I do have a vocabulary or lexicon. I don’t have a technique the way Graham or Cunningham had and required training to pull off.

RoseLee—It’s also an expertise. Trio A is a lot more difficult to execute than many people imagine.

Yvonne—Its innovation is it looks so easy anyone can do it. The continuity of it is the most challenging part. Anyone can do most of the moves, but putting it together is a whole other issue.

RoseLee—Then, lexicon or vocabulary also implies that you can put those pieces together.

Yvonne—In many different ways.

RoseLee—What is the story that gets told with those pieces?

Yvonne—The movements themselves don’t tell a story. In recent work, the reading of texts is interspersed with movement. The limitations of abstract dance is one reason I left for film. When I came back I realized a continuum of quotations and writing would give a wider context to mostly abstract moves. The piece I’ve been working on for the last years has basically two strands: the movement and the texts that are read by me and by others in the group. The elements have nothing to do with each other at all.

RoseLee—I’m intrigued about looking at your ability to use dance as a form of political commentary—as you did in the 60s—and how you subtly reintroduced this in your recent performance at MoMA, with the Rousseau painting and with texts taken from wall inscriptions in the Islamic wing at the Met. It was an arc between the earlier political conversations and current times and politics. I’m asking you to stand back from your own work—to be in the viewer’s shoes—and look at dance as a vehicle for meaning and intensity, for possibly changing people’s minds.

When you’re young, you’re absorbing everything: the world, every idea, reading voraciously. Then comes a point to make your mark and distinguish yourself.

Yvonne—Oh, well that’s a whole other issue!

RoseLee—Even if it’s one person in the audience who now needs to ask themselves questions about what they are seeing?

Yvonne—Excuse my vulgarity, but I have to say, I don’t give a shit about the audience! My niece saw the MoMA piece, The Concept of Dust, or How do you look when there’s nothing left to move?, which now has a different name. She said, “It was like preaching to the choir.” I wrote back to her: “There isn’t much preaching, all those quotations constitute historical narratives of one kind or another.” Maybe I should do more “preaching.” The choir needs support, needs shaking up. The choir needs a sense of solidarity and cohesion. So, I don’t see anything wrong with this complaint that you often hear when you introduce something specifically political to members of an audience who share your politics.

RoseLee—They need it for inspiration too…

Yvonne—No one who is a follower of Donald Trump is going to come to a concert of mine, or any postmodern dance. You kind of take that for granted. My vulgar remark is really a way of saying, “I don’t worry about the audience.” I accept that you can lead them to water but can’t make them drink!

RoseLee—At the same time, for someone who writes about your work, or presents it to the public, I wish the ideas that I respond to in the work to be evident, accessible to audiences. Yvonne, you are valued and read through the lens of the visual art world. Where is postmodern dance studied?

Yvonne—In the art departments. There are so many performance artists who come out of visual art.

RoseLee—It’s also because the art world gives absolute license to experiment. Expect the unexpected—it demands the unexpected—rethinking our moment in time, every moment.

Yvonne—It encourages it.

RoseLee—You’ve taught for years in art schools, in California, and before that in the Whitney program. It seems to me you are revered and followed more closely by students in the art world than by trained dancers—other than Baryshnikov!

Yvonne—My most recent experience teaching was for eight years at the University of California at Irvine in the art department. In all that time, maybe six dancers came to study with me.

RoseLee—There’s my point.

Yvonne—I taught a course called “Materials for Performance,” and it was mainly visual artists who were interested in performance who studied with me.

RoseLee—If you were to imagine, instead, teaching a class in a dance department—what would the conversation be?

Yvonne—Most dance departments are very conservative. Those kids want to jump around and use their training. No harm in that, but why not combine training with ideas about the world and other art forms? In the late 60s, the Harkness Ballet invited Trisha and Steve Paxton and I to talk about what we wanted to do with their dancers. I wanted to do We Shall Run. Mrs. Harkness, in her Spectator pumps, bun, and exquisite make up said, “How can you ask these dancers who have trained since childhood to simply run and walk?” And we were out the door! [Laughs].

RoseLee—We see more dance in museums and galleries.

Yvonne—I’ve always been ambivalent about the art world. It began with being the tail of Rauschenberg’s meteor—the economic imbalance was so apparent. We had no product, only our bodies to sell. There’s always been an underlying resentment on my part of this aspect of dancing, relative to the visual arts.

RoseLee—Now it ends up in this other strange place…

Yvonne—Where the museums are buying dances! That’s an ongoing and unresolved issue.

RoseLee—I look at it from a sense of responsibility, to support the dancer—not as a commodity. It’s not that there is a market. Rather, there is a real necessity for the art world to support the experimentation, the innovation, the mindset of choreography—to absorb its mechanisms for understanding spaces, relationships between bodies. It’s a research laboratory; there’s so much to learn from the dance world when it enters the museum.

Yvonne—Is it about noblesse oblige?

RoseLee—It’s also about finally acknowledging history. In the 70s this material was the corollary to “the dematerialization of the art object,” as conceptual art was called. Academics are finally saying this work needs to be recognized as central to shaping art history of the 70s. The ideal role of the patron is to be a caretaker for culture and to support artists. In order to do that, yes, I encourage a collector to buy an Yvonne Rainer—a drawing, an outline for a dance, a video of a dance—because this work must be supported and history must acknowledge it and institutions preserve it.

Yvonne—It’s still a nebulous territory, how you “buy” a dance. Say the originators of it are gone—do you still own the dance? The discussion is in process at a lot of museums.

RoseLee—Your most recent piece, The Concept of Dust: Continuous Project–Altered Annually, which, indeed, you have been performing in museums—at MoMA, in the Louvre. It contains a lot of different elements from your history.

Yvonne—The movements themselves are very set, but there’s indeterminacy in terms of sequence. All six dancers have solos. There are unisons and anyone can initiate a unison. It’s different at every performance.

RoseLee—So it’s a lexicon again?

Yvonne—Yes, it’s like verbs and nouns and they can come into play in different ways. I keep adding different texts and I read them in a different order in every performance.

RoseLee—How do you determine that?

Yvonne—It’s about the density of activity at any moment in the space. I’ve never believed in exits and entrances, so they’re there all the time. If you’re not actually dancing, then you’re on the side, watching, resting, deciding your next move.

RoseLee—And how do you keep track of time?

Yvonne—I look at my watch to see if they’re getting tired. It’s an aging group; the oldest is 70 years old. No, I am—I’m 81. The youngest is 41-42. There are things they do together—there’s a pillow used to cushion each other, a very old trope in my work. There’s a microphone I put in people’s faces with a text. I rush over to put a mic if I want a little more context or allusion.

RoseLee—So you’re directing?

Yvonne—In a way, everyone is directing—we are all making spontaneous decisions. As the primary director, I have already made “rules of engagement” with respect to limits and possibilities.

RoseLee—Your most recent work is as radical as it ever was. It asks the big questions about the nature of dance, politics, individual psychology. Your lexicon or vocabulary is now a rich one—an accumulation of time, gestures, and ideas.

Yvonne—All I can hope for is that the work will impact a few people similarly to what I experienced when I first saw Jean Vigo’s Zero for Conduct, balancing, Rauschenberg, Merce, and what Trisha was beginning to explore. I have no doubt that comparable experiences of revelation are available to 20-year-olds today.

This story originally appeared in issue No. 8 of Document.