The pair discuss the intersections between Edward Snowden, Brexit, and blockchain technologies.

I have had the pleasure of knowing and working with Simon Denny since 2008, when I invited him to participate in a group show titled “Display with Sound” at the now defunct International Project Space in Birmingham [United Kingdom]. His practice was on the cusp of a new direction: Less overtly driven by formal concerns than earlier work, it felt stimulated by a more research based approach. This was evident in the exhibition “Deep Sea Vaudeo” at Galerie Buchholz in Cologne, which illustrated the technological evolution of the television from cathode ray to the LED screens via aquariums. His ongoing research into television as an artists’ medium and a channel for distribution coincided with the end of the UK digital switchover from analog television in 2012 and an exhibition that I was in the midst of curating entitled “Remote Control” at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. Without hesitation, I invited Simon to participate and cocurate part of the exhibition. His artistic contribution featured an obsolete analog television transmitter that dominated the lower gallery, which was re imagined as an image based work for the 2013 Venice Biennale exhibition “The Encyclopedic Palace.” Since then, he has presented solo exhibitions at a wealth of internationally respected institutions including Kunstverein München, mumok, Portikus, Museum of Modern Art PS1, Serpentine Sackler Gallery, and WIELS. In between, he managed to find time to represent New Zealand at the Venice Biennale in 2015 and present the exhibition “Secret Power.” His latest project, “Blockchain Visionaries,” premiered at the Berlin Biennale and will be reconfigured at Petzel Gallery in New York this fall as “Blockchain Future States.”

Matt Williams—It probably feels like a lifetime ago for you— given the number of major exhibitions that you have produced since the Venice Biennale in 2015—but your solo presentation “Secret Power” for New Zealand felt like a substantial departure from past exhibitions. The ambition, the intensity of the research, and production involved to present such a comprehensive, all encompassing body of work on such a grand scale must have been incredibly demanding. Especially given that it existed over two sites, Marco Polo Airport and the Marciana Library, and comprehensively illustrated a timeline of symbols and images through history to reveal a sophisticated codex. What sparked your interest to develop such a substantial body of work?

Simon Denny—A strong driver for the development of the exhibition was the parallel between the subject of the show—which was, nominally, the imagery found in the [Edward] Snowden NSA slide leaks—and its potential venues. One, an airport, a place where information is kind of obscured, where you cross borders and have to show your passport and information about who you are and where you’ve been and where you come from. (And this information is used to determine whether you are appropriate to pass through or not.) And the other, this amazing renaissance library, the Marciana Library, with its ornately decorated interior full of imagery intended to depict the value of knowledge. This imagery has been legible to different people at different times in different ways, but is maybe now only legible in the way that it was first rendered to historians.

“Bitcoin can be seen as something that, while it distrusts the existing global monetary system, it doesn’t want to replace it with a reassertion of nationalism.”

Some of the paintings in the library share similar visual themes to the material in the slides. I wanted to gesture towards a sense of continuity of images over different epochs that visualize the value of data and therefore contain political content in them. Both are produced within a very different nation state’s organizational framework at very different times, but when presented beside each other—monumentalized as kind of connected art— you get a sense of some kind of timeless code or a secret power emerging from the imagery, somehow mapping knowledge.

Matt—The familiar and playful aspect of the visual imagery is subtly manipulative in the way that it operates successfully on a superficial level, while also illustrating complex systems of information.

Simon—When I’m developing a project, I often aim to make things that are complex and obscure and fun and engaging; an experience that people can have beyond just seeing data. For “Secret Power,” I looked extensively to frame the complex imagery of David Darchicourt, an art director at the NSA from 2001/2012, and possibly the author of a lot of the Snowden slide imagery. He was the senior designer, and created lots of visuals for different departments there. I focused on work that he had put online as a kind of portfolio, showing his skills and aligning it with the Snowden material, which was not clearly authored, to create a comparison as a starting point. [I thought] about him as a heroic author [or] artist figure at the center of this amazing, crazy image production that happens in the NSA. Using the figure of Darchicourt in a place like the library—which is treated with reverence because it contains so many masterpieces—also lends an important tone to the material. For example, the first European world map to include Japan sits alongside commissions from Darchicourt and images ripped from his website, which are monumentalized in scale and material. It was an opportunity to reframe the NSA slides and to look at them from a more playful perspective than from what one gets from established news sources, which can seem dry.

Matt—I recollect walking up the steps to the library and Simon Denny how impressive it was visually upon entering. I felt privileged to be allowed access, it was incredibly theatrical and implied a cinematic narrative, akin to something you might find in a Hollywood movie about the Illuminati or a similar faceless, Big Brother style organization. The objects and visual information alluded to an alternative, parallel history and the political machinations that drive it. Does bringing together this kind of complexity involve a team?

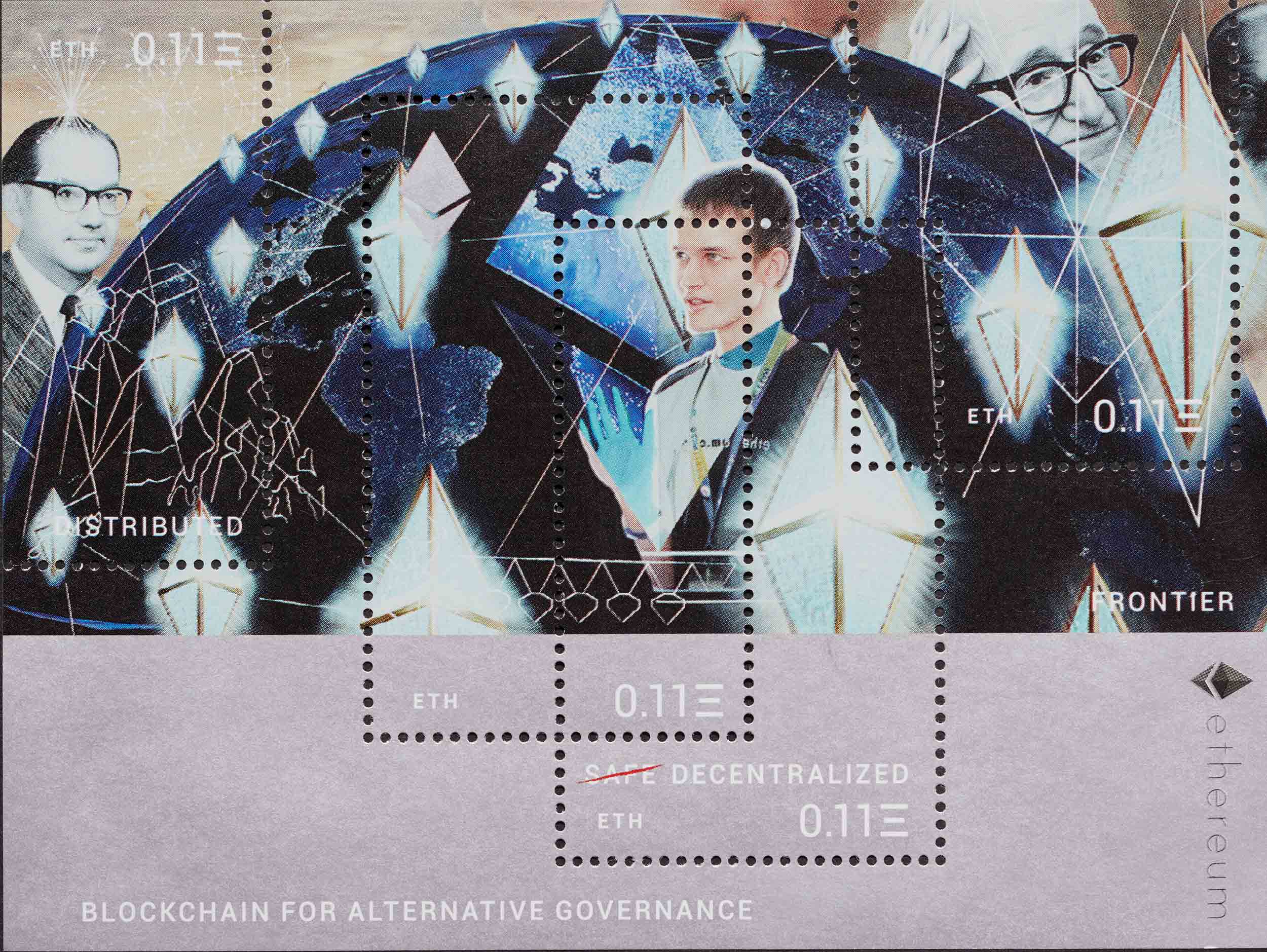

Simon—At the time, I really got into learning while making, and learning through making. I kind of worked that into the process more intensely, into my artistic method. Of course, when you’re learning all the time—and not an expert yourself on a topic you are making an exhibition about—you rely on the people around who are knowledgeable about these topics. Now, pretty much every show I make involves a number of people, from logistics to researching and crafts. This project that I just finished for the Berlin Biennale, which will travel to Petzel in New York in a different form, is about Bitcoin and blockchain technology and where that’s leading governance at the moment, and also involved many people. A number of partners were required to unpack and make accessible what can seem like quite confusing technology. I collaborated with an advertising company to make an explanatory video. I also collaborated with a postage stamp designer, and learned about the processes involved in successfully creating something with illustrative significance within a very small amount of space. I wanted to condense the audience’s experience of my work—which is usually through a large, immersive installation—into something the size of a stamp.

Matt—The transition from “Secret Power,” which was predominantly about the language of codification, to “Blockchain Visionaries,” which is about transparency, was, I can imagine, a challenging change of direction. The ethos of blockchain feels radical in the sense that it basically undermines established institutions and financial protocols that society has been operating under for hundreds of years. Particularly if it is successfully implemented and accepted, the impact that it has on financial structures and society could be seismic.

Simon—Totally. Interestingly, the UK’s Brexit situation resonates with this project, because it’s about imagining a different governance system based on a new way to share, keep, and trust information. The basic idea of blockchain is that it replaces the trusting third party elite to oversee an exchange or event. It starts with digital money, from the idea that if I gave you an amount of money in the past, we needed a bank to tell us that that transaction happened. Now, it can be in this code, which is indestructible and distributed across the entire network of people using it. The assumption then is that this idea can also be applied to other things you need trusted verification for: a vote, or some kind of issuance of a certificate or a contract. These things that generally rely on elected elites to verify can be transferred to a blockchain based network. This technology makes the possibility of exiting a traditional state system and having some sort of alternative via a global crowd or a localized closed system a real possibility. A scalable exit could be enabled by this technology and thinking. It feels incredibly poignant, especially at this time in history when many countries are fighting what feels like an ideological war in the sense that people are either pulling back towards nationalism or accelerating global capitalism.

Matt—What felt apparent during the Brexit campaign was the level of distrust and apathy towards politics and politicians in general. Retrospectively, it felt like a protest vote by the working classes or “losers” of globalism, because of an overwhelming sense of isolation and disconnection from the central governing base. Or, to put it bluntly: What had neoliberal economic and social policies done for them?

Simon—That was also my sense of some of the essential issues in Brexit. And the ideas behind the invention of Bitcoin and the blockchain ledger resonate with these sentiments. The notion that one doesn’t need a small group of people at the top overseeing the fairness of the system as a whole is something that really motivated this technology. It’s a technological vision of the network—or the people—owning the means of governance, and its distributed structure being immutable. It’s interesting, though, because in a way, Bitcoin can be seen as something that, while it distrusts the existing global monetary system, it doesn’t want to replace it with a reassertion of nationalism—like Brexit or populist campaigners like Trump. It, instead, looks for a postnational state globalism that is more inclusive by design than the existing system.

Matt—How did this content manifest in your presentation for the Berlin Biennale? What were some of the ways you managed to foreground these issues about sovereignty when often they are only in the background of perceptions of Bitcoin and blockchain?

Simon—Like with my pavilion in Venice, the site of the exhibition had a significant impact on the way I framed the content. I was lucky to work with the curators, DIS, closely in the selection, and we found this management school, which is actually housed in a former GDR communist state council headquarters. It’s filled with these amazing communist mural masterpieces. We managed to get access to this empty room with this giant mural of a dove flying over industry from the communist period—literally an engine for liberalism inside the architectural shell of communism. Ideologies compared across time. The illustrative language of the communist murals also suggested to me that using a format that was inherently illustrative as the keystone to the exhibition would be a good thing. And that is where I arrived at the idea of making stamps. Postage stamps are at once physical currency; they’re real money, they’re issued by a state, they carry state defined imagery, and they stand for a kind of trusted network of distribution—the postage system. When you give your post in, you trust that the state will deliver it to the right place and it’s a safe network. All the important issues around blockchain were paralleled in stamps somehow. I also knew a designer, Linda Kantchev, who had made some stamps for the German post and grew up in the GDR, so she was knowledgeable about communist imagery and illustrative techniques that make a good contemporary stamp. The idea was to create special stamps for these blockchain companies that would describe their vision for a new world based on encrypted networks. The more I looked into these companies and their various takes on blockchain, the more I also realized that at the base of blockchain is a kind of classical economic liberalism on steroids. The imagery we created to describe this technoliberalism also was a fantastic contrast to the ominous communist murals in the building. Both are kind of inspiring images that are supposed to carry essences of wonder, dreams of a technologically enabled world that is owned by everybody on the network.

Matt—Highlighting the parallels between communist ideology and blockchain through the physical architecture and imagery of the presentation in Berlin feels pertinent. But given the demise of communist governance, I’m guessing that the comparison with blockchain has also attracted criticism?

Simon—The critics of blockchain say technologists are kind of building a “1984” scenario, where the computers are supposed to be taking care of us and trust is given to machines over people. Of course, computers can be hacked, which is scary and raises questions about supposedly infallible systems. I think the tension between the utopic vision behind blockchain and the more complicated reality of how things progress gives the topic and, hopefully, the work a kind of window into the sublime.

Matt—The New York iteration of the exhibition will manifest as a series of board games. What was the significance of that as a medium?

Simon—Without the communist building and murals that frame the Berlin presentation, I needed to find a format for the exhibition that foregrounded the sovereignty issues more clearly than just the postage stamps alone. I think this kind of struggle and competition for mastering blockchain felt a lot like a kind of land grab. I have made a lot of work based on the structure of gaming computers, and my research on the beginnings of the founder myth of Bitcoin had led to the fact that part of that myth is based on Pokémon characters. Also, one of the companies I was looking at—Ethereum—likely lifted their logo from Magic: The Gathering card games. Gaming was kind of everywhere in the blockchain landscape. I made some board games as part of the Venice pavilion also—actually copies of the former NSA designer’s creations for educational game manufacturers—and thought they were a great format for diagrammatic explorations of content. My work often takes a kind of sculptural infographic format, and I thought the board game Risk would be a great way of bringing all this material together. So, along with the stamps, I’ve made Risk editions and a global map to represent the various worldviews the three blockchain companies I am working on are based on.

The exhibition will be at the Petzel Gallery in Chelsea, a stone’s throw from Wall Street, which is pertinent because, ironically, a lot of the speculation around the technology comes from banks and financial institutions. They are seeing the potential in blockchain as a method of streamlining. If blockchain means that you don’t need people to verify information, then it makes a lot of settlement jobs in banking redundant. Large commercial banks can half their staff based on this technology if it really works. They’re building private blockchains that can be applied to existing currency and scrap the idea of alternate currency like Bitcoin, and just use the technology for streamlining.

This conversation first appeared in Document’s Fall/Winter 2016 issue.