The artists discuss process, the significance of their mothers in their work, and how Lawson creates the intimacy that is signature in her photographs in Document's Spring/Summer 2016 issue.

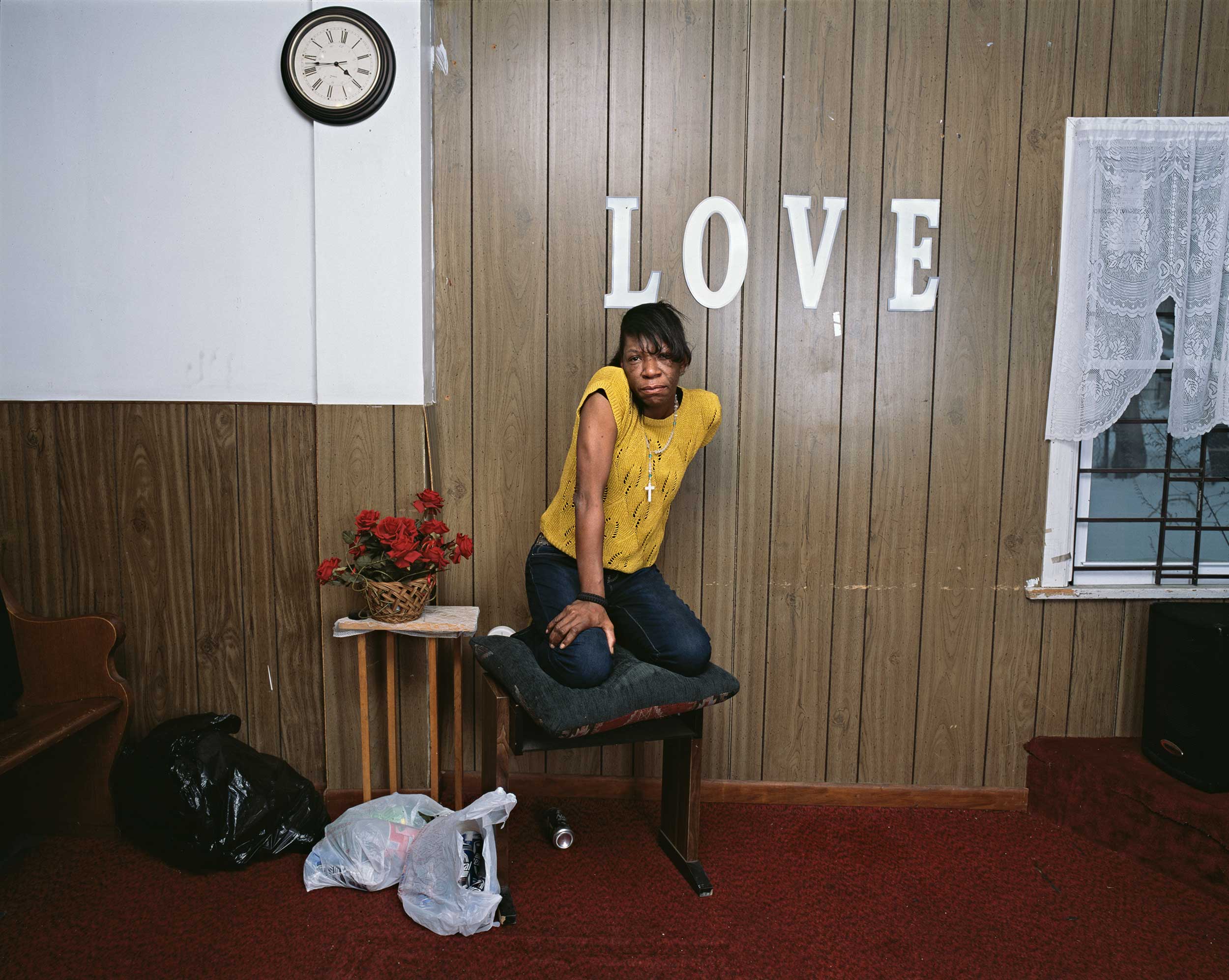

Deana Lawson and Mickalene Thomas share several commonalities in their practice. The artists both look to their mothers as a source of inspiration; both use working-class African-American homes as not just a backdrop in their photography, but also as another layer in their work; and both reference classical poses in their contemporary imagery. In Thomas’s recent dual exhibition at Aperture Gallery in New York, she played the roles of artist and curator; part of the exhibition was dedicated to her own work, while the other displayed a group of artists— including Lawson. Here, Thomas and Lawson talk about process, the significance of their mothers in their work, and how Lawson creates the intimacy that is signature in her photographs.

Mickalene Thomas: I’m always in awe and amazed at how you get strangers to expose themselves to the world, revealing vulnerability. How do you connect to strangers and get them to express themselves in such raw and beautiful ways? It’s rare to be able to connect to someone on a level that you do, then allow them to feel comfortable enough to expose themselves.

Deana Lawson: I think it’s a gift, and part of it is an honest curiosity on my part. When I’m drawn to a particular stranger that attraction is very real. There is something about that person—whether it’s the eyes or the walk or the dress—that I’m actually taken by and I have a moment of pause. If I don’t ask that person to photograph them in that moment, I kick myself afterwards. I’m like, “Why? I should have asked that person on the train.” It’ll sit with me for months on end. I always tell myself that any time I have that feeling where I have to take the photo, I need to follow through on that instinct or else it’ll haunt me.

Mickalene: It’s rare for someone to be able to connect on a level that you do. That’s a special talent, not everyone can do that; not every photographer familiarizes themselves with their subjects on a personal level. For me, I tend to work with people I know: family, friends, and lovers. Do you build a real dialogue with [your subjects], having conversations well before the photos even happen?

Deana: Absolutely. Oftentimes it might even involve a meeting before the photo shoot; we might meet in a café and have a conversation or speak on the phone.

Mickalene: You have a great eye for social and cultural dynamics, formally and compositionally. You know exactly how you want the subject to sit in a space. In some of your portraits, you’ve incorporated elements that add a layer. In the environment, does it take a moment before you recognize the rhythm and the positioning of the sitter? What is the moment where you go: “That’s it! This is the shot!”

Deana: Actually I survey the environment quite a bit. I’m working often with a large-format camera and studio lights, so wherever I choose to set up, that has to be the spot. I actually walk around the space for quite a while before I decide, “This is where it is.”

Mickalene: Could you describe the role of environment and space in portraying your subjects? Is there a narrative or a scenario that’s happening that gives the subject weight?

Deana: Diane Arbus’s work, how she used environment, was inspirational—particularly this picture of an older woman, curtains and all the bric-à-brac around—there was something psychological about it that expanded the meaning or how we are to interpret the subject in this space. With African-American culture, or really the environment I grew up in Rochester and the way my mom decorated our house—I remember the plastic on the couch, and carpet is a big thing for me. She also had this aspiration for middle-class life—we were very much working class. She always wanted to move to a bigger house in the suburbs, but we never got that dream. The way she dealt with that was to redecorate every year. If you look at pictures of our house throughout the years, you’ll see the kitchen changes, the living room changes. In that decoration or re-decoration there was a need to make the space her own. So with the photographs and how I treat the subject and how I place them within the environment, I definitely feel there is an1 interaction I want to highlight.

There is a similarity between the presences of our mothers in our work. For my work, it’s not as directly as yours. But I remember a talk where you showed a photograph of your mom. When I give a talk there is a similar picture I have of my mom, too.

Mickalene: You do?! You have one similar?

Deana: Yes, it’s my mom posed on the carpet. She made a pin-up calendar for my father for their wedding. How has your mother shaped your work aesthetically?

Mickalene: I make the work I do because of who my mother represented in the world and how I perceived her. Everything about her allowed me to see and understand beauty and my body and conceptualize who and what I am in these spaces I create. There was an overwhelmingly strong need for me to understand the mother/daughter connection. This was a starting place and thread physically and viscerally and formally to begin with the black body. It made sense for me, if I was going to do portraits of the black to start with my mother. She was my first subject because I didn’t feel comfortable asking someone else. I am an extension of who she was. I see all of my work as self-portraits, even though I’m working with others. I’m more comfortable working with women that I know. Women are beautiful, sexy and possess a power that is insatiable. Most of the women that I work with are women with confidence, strength, and sensuality—all of the attributes I covet. There’s an energy about them that I see in myself. They are a mirror of self-reflection. Some I see as portraying an extension of who I am.

One thing about your practice I did not know is that you use drawing as tool, inspired by things you see during your travels or defined as developing a clear idea before you begin shooting. I’m curious to see what your drawings look like; can you talk about these drawings?

Deana: Interestingly enough, I don’t actually draw the pictures. My former partner, Aaron—who is still a really great friend—does. I dictate to him a drawing I had in my mind and he’d draw it out. The drawings help me think through it. Also the drawings help the subject to understand what it is that I want.

Mickalene: OK, yeah.

Deana: Oftentimes I’ll show the subject my work; I show them a small album of 8×10 prints to give an idea of how I work. Then if I want them to perform a particular role in a photograph, the drawings help them to understand it. Even more so if there is nudity involved, the drawings help them to feel more comfortable with what they’re being asked to perform, on many levels. Do you draw at all?

Mickalene: No, I don’t. My method is through photography and then my collages. I use my collages as my formal aspects to compose the images. Not necessarily for my photographs, but for my paintings. You have such an amazing process and a unique methodology in how you connect to strangers. What is the gaze for you and your subjects?

Deana: The direct gaze for me is definitely an expression of confidence, or being in one’s skin. It’s recognition of looking, but also of being looked at. Also, confidence to say: “I know you’re photographing me and I’m also engaging in this collaboration with you.” It’s one of power, actually, too. The power to say: “Yes, I am halfway in clothes; I have on a bra and some stockings; my stockings have a run. And I have a do-rag on my head. I look beautiful. Look at me.”

In addition to the direct gaze, the pose is so important. Sometimes the pose will make or break the photograph. What I’m interested in is expanding beauty or this idea of beauty and incorporating what you call “unapologetically raw” into a notion of beauty.

Mickalene: The residue of this is so palpable that sometimes they are painfully raw—that’s where the beauty comes from. What I love about your subjects and your photographs is that they’re all so unapologetically truthful regardless of what artifice is layered. They’re just so truthful with meaning and stop you in your tracks.

This article originally appeared in Document’s Spring/Summer 2016 issue.